By Amanda Hill, 31st July 2024

“The Royal Courts of Justice (London’s High Court) is an enchanting building on London’s Fleet Street.” So says the Royal Courts of Justice (RCJ) website, promoting public tours of the Grade 1 listed building, the centre for many of the most important court hearings in the United Kingdom.

I have observed two dozen or so Court of Protection hearings, but mostly in the regional courts, and always remotely. When I realised that I would have some time to spare while passing through London on the morning of 12th July 2024, I hoped that I would be able to observe an in person hearing at the RCJ.

This blog is about that incredible experience – and I hope it encourages readers to go there in person.

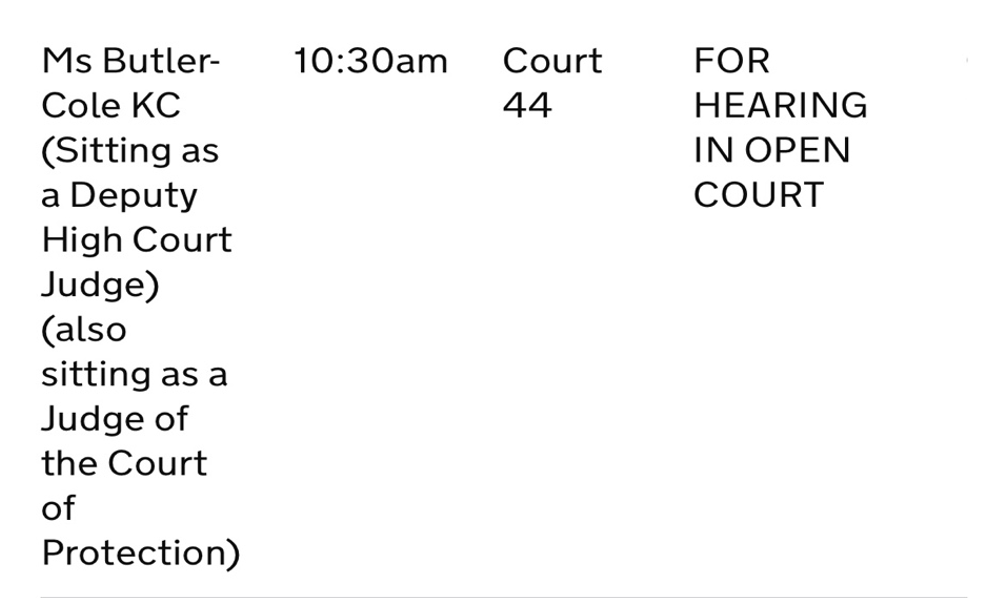

The first step of my journey was finding a suitable hearing. RCJ COP hearings that are open to the public are only published the evening before and it was pot luck whether or not I would find something appropriate. I knew to look at the Open Justice Court of Protection Project (OJCOPP) Featured Hearings, usually RCJ hearings, which are highlighted so as to enable anyone wanting to observe to send a request for the link (for remote hearings) or plan to attend in person. My luck was in! The evening before my trip, I saw this on the OJCOPP website:

And I recognised the name of the judge! Victoria (Tor) Butler-Cole KC is a barrister who also sits as a part time judge. She’s also one of the lawyers on the Advisory Group of the OJCOPP. I’ve seen her as Counsel in remote hearings but I was very excited about the possibility of seeing her in action as a judge, in person.

The listings for the Royal Courts of Justice (unlike the regional court listings) don’t say what the hearings are about. They also don’t say how long the hearings are due to last for and I only had until 12.30 before I would have to leave. I was worried that I wouldn’t be able to leave the hearing if it was still in progress. But I learnt that observers often leave during hearings, especially if the hearing is long. This is the same for remote hearings, when observers can log on and log off at intervals.

I also wasn’t sure what time to arrive at the court for the 10.30am start time. This message accompanies the RCJ listings for in person hearings on the OJCOPP X (Twitter) site: “To observe in person, go along to the court, leaving enough time to get through airport style security”. I’ve often wondered what this means in practice but I decided to play it safe and get there early. The RCJ opens at 9.30am so I aimed to get there as soon as possible after that. I travelled by tube and got to Holborn underground station about 9.30am and walked down Kingsway, towards the Strand.

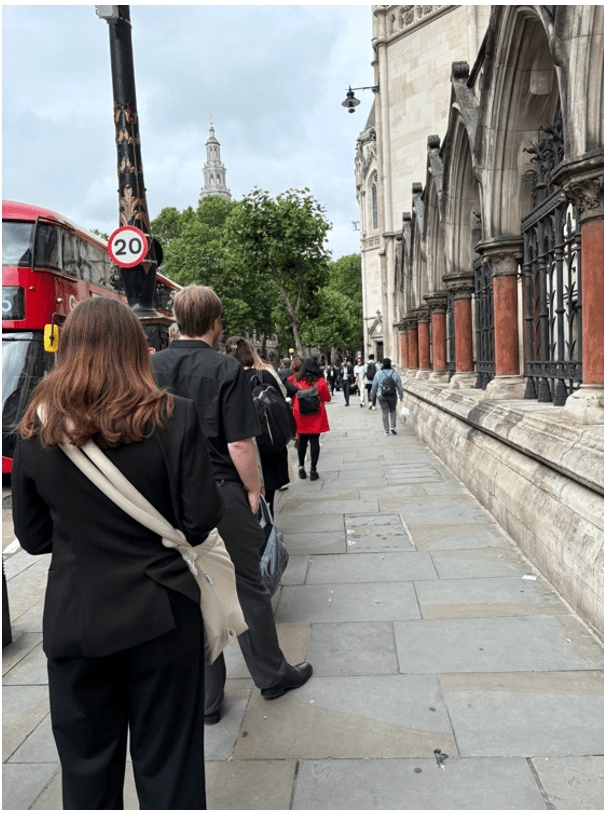

It was a bright, sunny day and I enjoyed being in this part of historic London, especially as I had worked near here many moons ago. All around there were signposts reflecting the legal heritage of the area, such as to Lincoln’s Inn and The Temple. I reached the semi-circle Aldwych at the end of Kingsway and saw Bush House in front of me, the famous old building which was previously the headquarters of the BBC World Service. Following the signs to the RCJ, I turned left and carried on walking to the court. It had taken me about 10 minutes and I arrived at 9.40am.

My heart sank when I arrived. In front of the main entrance, and stretching away from me, was a long queue of people. I was very relieved that the hearing I wanted to observe started at 10.30 and not 10am. I joined the back of the queue and took in what was going on around me. (Celia Kitzinger, who has more experience of observing in the Royal Courts of Justice, tells me there are often short to medium queues but she’s never experienced anything like what I experienced today.)

Next to the entrance on both sides were various groups of people protesting. It seems it was a busy day for hearings at the RCJ and I later learned that a couple of high-profile cases had attracted people to the court, to observe, report, participate in or protest against (see photos below).

There seemed to be lots of different kinds of people in the queue: they could have been lawyers, journalists, family members and observers. I guessed that the smartly dressed people were the lawyers and a few of them were looking concerned about time. Lots of people were standing around the entrance too, and I saw a few people pulling boxes of documents on wheely trollies.

I moved slowly forwards and took in the magnificent grey stone facade of the building. It looked like a gothic cathedral. As I approached the entrance, I saw that there were steps and I wondered about accessibility for wheelchair users. I got to the front and was surprised to see this sign (in photo below).

The general public, like me, are admitted – and were being admitted despite the sign. I found the sign misleading and potentially off-putting for people who didn’t know otherwise.

I reached security at about 9.55am and was through in a few short minutes. I had to place my rucksack on a moving conveyor belt (the “airport style” security) and I was “scanned” by a security guard in a very unthreatening way. I took the opportunity to ask him about access for wheelchair users and he said there were two side entrances they could use. I hadn’t seen any signs for these outside though. In terms of accessibility, there were also doors which opened automatically, toilets marked “disabled” and lifts to other floors. There were quite a few steps though and I didn’t see any wheelchair users during my visit. I also asked whether I would have been able to bring my airplane cabin sized luggage in and he said yes, as long as it could go through the X-ray machine. I did see a lot of lawyers’ bags, which were fairly big, going through. My rucksack went through without stopping.

Once through security, I took a moment to survey the scene in front of me. I wanted to take photos but signs at security had made it clear that photos were not allowed. I looked up and saw the most amazing vast vaulted ceiling, many feet above me. I was standing in a large hall, the Great Hall, with people milling and rushing around, various signs with gothic style writing peppering the numerous corridors leading off from the main space. Impressive stone columns broke up the vast floor space; metal, triangular chandeliers hung from the ceiling, and classic stained-glass windows filtered light into the hall. The inside was even more impressive than the outside. My powers of description don’t do it justice. You can see some images of it here: https://theroyalcourtsofjustice.com/gallery/

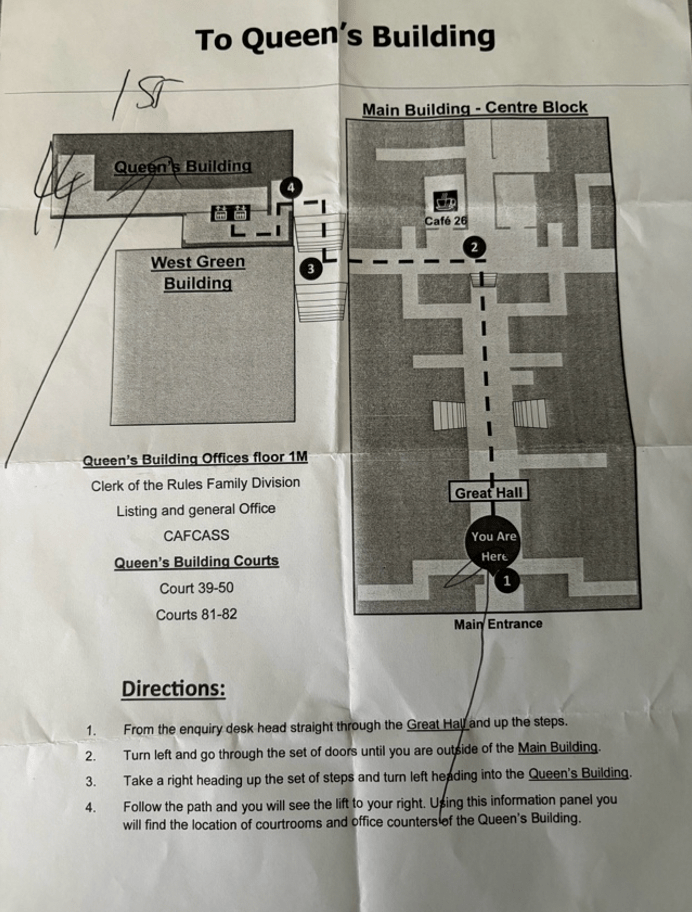

A lot of people had made their way in before me and it was very busy. I started heading off in one direction before realising that I didn’t have a clue where Court 44 was and I couldn’t see any signs for it. I spotted an enquiry desk in the middle of the hall fairly close to security and went to ask where I could find the court. A man flicked through various A4 sized papers, eventually coming across the hearing I wanted to observe. He ticked the paper, and told me that, yes, I could observe it. Not all hearings at the RCJ are open to the public so he was doing his job in checking, but I knew from the list the night before that the one I wanted to observe was “in open court”, so I was going to go in anyway. He told me Court 44 was in the Queen’s Building and he gave me a map.

He also told me that Court 44 was on the 1st floor and that I should get the lift up to it. I headed off in the direction he pointed at, trying to make sense of the map. As I moved towards the far end of the hall, I spotted a fully gowned and wigged barrister striding off, his gown billowing behind him. This vision increased the feeling I had that I was in a hallowed building.

The Queen’s Building was much more modern, built in 1968. I suddenly thought that maybe I should take a “comfort break” before heading to the courtroom. I followed the signs which led through the Queen’s Building and to another linked building. To my right, behind a glass wall, I could see individual tables of legal teams waiting for their hearings to begin, heads bowed together as they discussed their cases. On my return to the Queen’s Building, I took the lift to the 1stFloor. As the lift rose, I was conscious of time ticking on and I was feeling quite nervous. I still didn’t know what I would do when I reached the courtroom and it was now 10.15. I remember thinking how imposing and intimidating it would be for a family member or ‘P’ attending a hearing.

Coming out of the lift, I could see a wall in front of me, dotted with doors with various numbers on. Straight away to my right I spotted one table that was occupied, outside Court 44, and I recognized the lawyer sitting there, talking to a smartly dressed lady who I guessed was a solicitor. It was Ian Brownhill, and I recognized him because I have observed various hearings he has been involved in. He is another member of the OJCOPP Advisory Group and has also written blogs for the OJCOPP, including this one: When P stops eating and drinking. I felt as though I was meeting a COP legal celebrity and I was delighted that I would get to see him act in person. Plucking up courage, as I was conscious that they would be preparing for the hearing, I went up to him and introduced myself as a member of the OJCOPP observer’s group. I told him that I wanted to observe the hearing and that as it was my first time observing in person, I didn’t quite know what to do. He amiably told me that it would start at 10.30, when the door would open and I could go in. In the meantime, I should wait.

I sat down at a nearby table. There were no other hearings on the first floor at that time and it was very quiet, in stark contrast to the noisy Grand Hall. I looked around and I noticed that there wasn’t a listing on the board before Court 44. But I did see a sign that said “Private No Admittance” and “No entry to the public save for accredited press/media representatives”. I was puzzled by this as I knew that I was allowed to observe. As time passed, a couple of other people arrived and stopped at the table where Ian Brownhill sat. I could tell that they were discussing the case (I heard the words ‘declarations to be made’). I didn’t particularly listen in, mainly because I was busy making notes for this blog, and trying to remember everything, especially as I couldn’t take photos.

Around 10.25 the door was opened by the court usher and I followed the legal people in. The room was not that large, I’m guessing about 40m2. At the far end, on a raised area, was the judge’s chair behind a wooden wall that separated the floor of the court room. High on the wall to the top right was a large TV screen, set up for remote participants, including any remote observers. It was interesting to see how remote parties or observers appear from the point of view of those in the court room. This was obviously a hybrid hearing and a microphone was moved in front of Counsel during the hearing. In front of the judge’s area, after a space for the usher’s seat, were about 8 rows of green cushioned benches, each about 10 metres long. Ian Brownhill suggested that I sit in one of the last two rows and I made my way to the middle so that I could see the judge clearly. I was the only observer. The people on the remote link turned out to be treating clinicians.

Two other barristers had entered the court room and were sitting in the front row. I later learned that they were Bridget Dolan KC (for the applicant) and Brett Davies (for the Local Authority). Ian Brownhill was acting for the Official Solicitor, representing the protected party ‘P’ in this case. Bridget Dolan and Ian Brownhill had their instructing solicitors (I assumed) sitting behind them. Nobody was wearing wigs and gowns. Before I sat down, I asked Ian Brownhill if I could have a copy of the Transparency Order and the position statements. He passed this request to Bridget Dolan, who came over to me and gave me a copy of the Transparency Order and her position statement, from her lever arch file. We had a short discussion about open justice and I asked why there were the signs outside the court stating that the public can’t be admitted. She told me that the court rooms were multi-purpose rooms, and were also used for Family Court hearings that were generally held in private. She told me that if she remembers, she turns the signs over when there are COP hearings here as public observers are very welcome. She said “The COP is always open”. (This isn’t strictly true as sometimes hearings are in private and judges don’t admit observers. There have also been closed hearings that even family members of the protected party don’t know about. I knew the statement was made in good faith, though.) I appreciated her taking the time out from her preparation to speak to me.

I took out my laptop, ready to take notes, having checked beforehand that it was allowed. I could also have my flask of water, although no other food or drink was allowed (except cough sweets!). At just after 10.35, the judge entered and we all briefly stood up. After everybody had sat down, Ian Brownhill introduced everybody and mentioned that there was an observer present. Tor Butler-Cole looked up at me and gave me a faint smile to acknowledge me, which I appreciated.

The hearing started and a summary was provided for my benefit. Cases were presented and evidence provided by the clinicians as witnesses. At 12.30 the hearing adjourned for 30 minutes to allow the legal teams to discuss some important issues. It was a perfect moment for me to leave. Bridget Dolan came up to me just before I left, to ask me if I had managed to understand the hearing as it was covering some quite technical points. I explained that I had followed quite a bit of it and it had been a really interesting experience. The judgment was subsequently published on Bailii here and I was glad that I could find out what happened after I left the hearing. Like many COP cases, the subject matter of the hearing was difficult to listen to and it brings home the important matters that COP hearings consider and how decisions impact individual people.

As I left the courtroom, the teams were around the table in the corridor again, heads bent down, discussing the case and aiming to go back into court with an agreed position. I headed back out through the Great Hall, reflecting on my experience.

As an observer, it had been very positive and I had been made to feel very welcome. I would highly recommend visiting the RCJ to observe a hearing as it felt very different to remote RCJ hearings I have observed. I’m sure that lawyers who have frequent hearings at the RCJ probably feel quite blasé about the surroundings but I had been very impressed, both by the building and the process of observing. Although I’m sure that future occasions won’t be quite as memorable as the first time I visited this magnificant building, I hope to be back many times in the future.

Amanda Hill is a PhD student at the School of Journalism, Media and Culture at Cardiff University. Her research focuses on the Court of Protection, exploring family experiences, media representations and social media activism. She is on X as @AmandaAPHill and on LinkedIn here

Such a thoughtful and engaging account of your first in-person observation at the Royal Courts of Justice! Your reflections bring to life both the grandeur of the building and the human side of observing Court of Protection proceedings.

Thanks for encouraging others to experience open justice firsthand and for highlighting the value of seeing the judicial process up close.

LikeLike