By Celia Kitzinger, 3rd January 2025 (amended 7th March 2025)

Update: At the February 2025 hearing, Claire Martin – a core team member of the Project – made oral and written submissions that the defendant should be named. She was successful. We will post a link to Claire’s blog about the February hearing as soon as it is published. On 7th March 2025, in the light of an email received from P’s legal representative, some (relatively minor) changes have been made to this blog post: they are not “corrections” to anything previously published, but reflect the sensitivities of this case. The amendments do not affect the substance of the reporting, or the views expressed.

The London Borough of Camden filed an application seeking committal for breach of an order made by HHJ Hilder. An in-person hearing was listed before the judge towards the end of December 2024. I observed via a remote link.

As it turned out, the defendant was unrepresented and the hearing was adjourned so that he could get legal representation.

In this blog post, I will (1) raise some issues about the fact that the judge has ordered, for the time being, that the defendant should not be named; and (2) describe what happened at the hearing.

1. Naming alleged contemnors in Court of Protection proceedings

The Practice Direction Committal for Contempt of Court – Open Court says that open justice is “a fundamental principle” and that “the general rule is that hearings are carried out in, and judgments and orders are made in, public” (§3). The alleged contemnor should normally be named and committal applications listed as follows:

FOR HEARING IN OPEN COURT

Application by [full names of applicant]

for the committal to prison of

[full names of the person alleged to be in contempt]

Any derogations from the principle of open justice “can only be justified in exceptional circumstances, when they are strictly necessary as measures to secure the proper administration of justice” (§4).

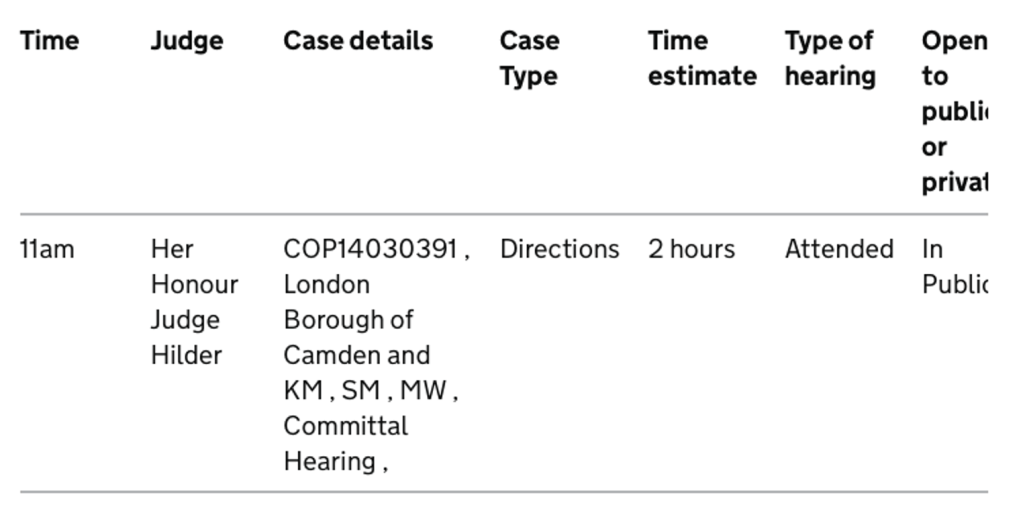

Here’s how this case was listed.

The list names the applicant (the London Borough of Camden) – albeit not as the applicant – but it does not name the defendant, the alleged contemnor. There is a list of initials but it’s not possible from this listing to know which of the persons referenced with initials is the defendant.

In fact, I knew in advance that “MW” was the defendant because a week earlier I’d been served with a sealed order made by HHJ Hilder informing me that “Pursuant to Rule 21.8(5) the names of the Defendant MW, the First Respondent ([initials]) and the Second Respondent ([initials]) shall not appear in the public listing of the hearing, and the involvement of any of them in committal proceedings shall not be published by any other means. The Court will consider at the hearing whether this prohibition should be continued or terminated…”.

Here’s what Rule 21.8(5) says: “The court must order that the identity of any party or witness shall not be disclosed if, and only if, it considers non-disclosure necessary to secure the proper administration of justice and in order to protect the interests of that party or witness.”

The order from HHJ Hilder gave no reasons as to why she considers that non-disclosure of the identy of these three people is “necessary to secure the proper administration of justice and in order to protect the interests of that party…”.

I made some deductions because, on the face of that order, one set of initials is followed by the words “(by her litigation friend, the Official Solicitor)”, indicating that she is “P” in these proceedings. I know from observing previous committal proceedings that judges are generally concerned to continue into committal proceedings the protection already afforded to P’s identity in court proceedings up to that point. I’ve seen this in the cases in which contempt proceedings were brought (and custodial sentences made) against James Grundy and Luba McPherson (as I described in an earlier blog post: Capacity and Contempt of Court: The case of LB): in both cases the defendant was named, but P was not.

I know that identification of the defendant causes judicial concern if there is reason to believe that they are a person who may not themselves have the requisite capacity – either to conduct proceedings, or to understand and comply with a court order. When this happens, they become, in effect, another “P”.

Capacity issues were raised in relation to both James Grundy and Luba MacPherson but this was after judgments naming them had already been published. At the Court of Appeal hearing for Ms MacPherson, the question of whether or not she should be anonymised going forward (perhaps moot, in my view, as this was clearly a case where that ship had sailed), was dealt with very quickly on the grounds that she herself opposed any attempt to conceal her identity from the public. I have also watched hearings concerning the contemnor now initialised as “LB”, whose name was briefly in the public domain after sentencing[i], but whose identity is now protected by a non-disclosure order pending a judgment on her capacity that due to be handed down in January 2025. (All these cases are discussed in my blog post Capacity and Contempt of Court: The case of LB.)

I do not think, however, that “MW”s identity can be protected by a non-disclosure order on the grounds of lack of capacity, because this would lead to questions about whether the order he is alleged to have breached should have been made in the first place (could he understand it, and the consequences of breaching it? Was he capable of compliance?). I am not aware of any capacity issues having been raised concerning MW.

The only other reason I can guess at as why it would be “necessary to secure the proper administration of justice and in order to protect the interests of that party…”that MW’s identity should be protected is that publication of their identities risks public identification of P, via jigsaw identification (that would be the “proper administration of justice” bit) and (it’s “and” not “or”) MW’s own ill-health, which is referred to in the order (“The Court is mindful that MW has health limitations”).

I’m not at all sure that these are good reasons for not naming MW, who is potentially facing a prison sentence. Taking the second issue first, why would it be in the best interests of someone with “health limitations” to risk being sent to prison, or fined, or having his assets seized without people knowing his name? And, in relation to the risk of identification of P, most of the defendants in contempt of court cases in the Court of Protection are family members or close friends of P, which means it can always be argued that knowing who they are might risk the public becoming aware of P’s identity. In practice, both in the Court of Protection (e.g. Re Dahlia Griffith [2020] EWCOP 46) and in the Family Courts (e.g. Manchester City Council v Maryan Yuse, Farad Abdi & the children [2023] EWHC 1248 (Fam)) family members have been named in judgments and there is no evidence at all that members of the public (or journalists) have subsequently tracked down the Ps or children concerned or harmed them in any way. The risk of identification is also mitigated in this case as the relevant surnames are different. In any case, as former PA journalist, Brian Farmer, wrote to the judge considering the naming – or not – of Luba MacPherson (the judgment was later published as: Sunderland City Council v Macpherson [2023] EWCOP 3

The vast majority of people won’t read your published judgment, they’ll find out about the case through the media. In reality, how many passengers on the Seaburn omnibus are going to read a report in the Sunderland Echo then try to piece together an information jigsaw? Dr Kitzinger and I might have the inclination and ability to track down your earlier anonymised judgment on Bailii, but will the average person really even try? Will they really start searching for the mother’s Facebook and Twitter accounts? Why would they? People have a lot on their minds at the moment. They’re struggling to heat their homes, struggling to pay food bills, war is raging, Prince Harry is on the front pages, Sunderland look like they’re going to miss out on promotion. In reality, this case isn’t big news and I suspect the vast majority will glance at any report, think how sad life is and how lucky they are, then turn to the back page to check the league table. (“Committal hearings and open justice in the Court of Protection”).

Finally, in this case, I think there may also be a concern from P herself about the identification of her family members and I notice (from another order of HHJ Hilder made after the hearing) that there are plans for her to attend the committal “remotely by MS Teams from the office of her solicitors”. So maybe it is P’s anxieties that have led to the non-disclosure order relating to MW. But I’m not sure that would comply with the wording: “necessary to secure the proper administration of justice and in order to protect the interests of that party…” where “that party” clearly refers to the defendant as opposed to P (a matter addressed in Esper v NHS NW London ICB [2023] EWCOP 29).

To be clear: I do not want to make an application to name P (or the other party initialised in the listing). My concern is only with naming the (alleged) contemnor. But in my experience, despite the Practice Direction and the Court of Protection Rules, as well as Poole J’s guidance in Esper that defendants in committal hearings should normally be named, in practice they are normally not named. The court is repeatedly finding reasons why they should not be. I find this concerning.

I wish Brian Farmer were still doing court reporting for PA and could come along to the next hearing in this case and argue the case for transparency with his customary aplomb. Unfortunately, he moved on a different job with the BBC about a year ago, and we public observers have rarely seen any journalists in the Court of Protection since then – and when they have attended, they have not addressed the court. It can feel like a disproportionate burden for members of the public to pick up the important work that Brian Farmer used to do – and obviously it should never have all relied on the hard work and dedication of a single journalist. I would give it a go, but will be out of the country and unable to attend the next hearing if it goes ahead as planned on 3rd February 2025. Moreover, jigsaw identification and the balancing of Article 8 and Article 10 rights is very fact-specific and I don’t know enough, at present, about this particular case to submit a written application for the naming of MW. So, I anticipate that this will be yet another committal hearing where the defendant is never named.

2. What happened at the December 2024 hearing?

The hearing started with an opening summary from the judge. The proceedings had begun, she said, with an application made in P’s name for assessment of her capacity across a number of domains including residence, care, contact, and use of social media. MW is a party to proceedings only in so far as the court is considering his contact with her. There are injunctions (with a penal notice attached) against MW, forbidding him from:

- having face-to-face contact with P, except as organised and supervised by the local authority

- sending her any communication between 6pm and 9am

- sending her any communication that refers to sexual activities, her health, members of her family, these proceedings, her work or study, or that threaten violence against her

- complaining about P to the police.

The local authority says that MW has breached these injunctions. There is a sworn affidavit from another family member and from a social worker reporting on visits and text messages, and both were available in court to give evidence.

At the hearing, I learnt about the family relationships between the people whose initials appear in the listings. I’ve chosen not to report the nature of those relationships here, because they would add to jigsaw identification in the unlikely event that MW is named in future. Also, suppressing this information now might make it more likely – if someone were to make an application to name MW in future – that the application might be successful if it could be accompanied by an injunction preventing any reference to the particular family relationships that pertain to these three people. I’d like to leave that open as a possibility for the court.

Although the hearing was in person, MW was attending remotely, with permission of the judge, due to his health issues. He was having difficulty with the technology, particularly in hearing what was being said (and it seemed his first language was not English, which must have added to the problems). I think he was holding the device to his ear, which meant we could only see the side of his head (and the red curtains behind him).

The judge opened the interaction by saying: “Mr W, it appears you don’t have legal representation: would you like to tell me about that?” and she reminded him that he’d been given a list of solicitors to contact. “Yes”, he said, “I contacted every single one of them. They said they could not help me”.

The judge asked if he had given the committal order to any of the solicitors. “Well, I don’t know what you mean, but I have tried all of the solicitors that have been sent to me. Here I am at a disadvantage to everything. My memory has gone and I am taking [18?] pills a day and [the cancer?] is making me forgetful. I’m not in my right mind, in other words, so I am really at a disadvantage.”

The judge asked “if the court is able to send a solicitor round to your house today, would you let them in?”. He replied enthusiastically, “Yes – oh thank you so much, yes! They are making it up here as if I am a full abled man without anything. Some of these things are not my fault and some of it is lies”. The judge intervened: “Let me stop you there. It’s important that you know you have the right to remain silent. I understand that you would like a solicitor”. He affirmed that he would, and the judge addressed the lawyers, saying that “funding will not be an issue” (that’s because of non-means-testing legal aid for committal hearings) and “it doesn’t seem appropriate for the court to proceed without a solicitor”. She then asked for a “proposal as to where I could go next”.

Counsel for the represented parties confirmed that they’d already sent MW a list of solicitors’ firms specialising in Court of Protection work – but the judge remarked (and I agreed with her analysis) that, “it’s not clear to me that he’s contacted them in respect of the committal”. In analogous situations I’ve observed in other cases, the hearing is then adjourned in the hope that the unrepresented party will acquire representation in the interim – and often that doesn’t actually happen, so cases proceed with the party still unrepresented several weeks or months later, and the outcome of the decision to adjourn turns out to have been simply more delay.

I was surprised to see HHJ Hilder being very proactive here. She instructed MW to stay on the line while she went to “see if I can make some arrangements for a solicitor”. I’m not entirely sure how this was done – it’s slightly unorthodox I think – but I believe that the judge’s clerk was tasked with phoning the firms on the list, overseen by the two lawyers. In any case, she returned with the name of a solicitor who was available and would be coming to visit MW that afternoon. By this time MW was no longer visible on screen, and nobody was sure whether he was actually able to hear her or not, but she addressed him in case he could, reminding him that the injunctions still applied between today’s date and the date of the re-listed hearing.

There was a brief discussion between the lawyers and judge concerning additional alleged breaches of the injunctions since the local authority had filed its original application. The judge asked for these to be filed by 20th December 2024 so that they could be considered alongside the earlier alleged breaches.

The judge also asked whether anyone wanted to make an application for the case to be heard in private (nobody did – but I suppose MW may do so once he’s represented) and then whether anyone wanted to make an application for naming the defendant (or either of the other two anonymised parties). Counsel representing P (by her litigation friend the Official Solicitor) made a case for keeping the first and second respondents anonymised – which I totally support – but indicated that the Esper judgment means that the identity of the defendant must be public (that’s my reading of it too). HHJ Hilder said she’d “read the Esper judgment with a fine tooth-comb” and seems to dismiss that suggestion. I got the impression that neither counsel had made representation to the judge previously concerning the naming or otherwise of the defendant and that the decision to protect his anonymity had been made (for reasons possibly opaque to both counsel as well as to me) without consultation. I didn’t feel able to make any application for MW to be named at this point (though HHJ Hilder asked whether I wish to and would have given me time to make an oral application): I was a bit daunted by the “tooth-comb” comment, didn’t feel I knew enough about the case, hadn’t been given any substantive reasons why the case had so far departed from the (putative) norm of naming the defendant (so didn’t know what position I might be arguing against), and I was concerned about making an application in any event with MW unrepresented (and no longer in court). I also thought that under the circumstances I was unlikely to be successful.

The hearing ended shortly after midday.

Celia Kitzinger is co-director of the Open Justice Court of Protection Project. She has observed more than 590 hearings since May 2020 and written more than 100 blog posts. She is on LinkedIn (here), and also on X (@KitzingerCelia) and Bluesky @kitzingercelia.bsky.social).

[i] The judge confirmed that she did not intend the new non-disclosure order in this case to apply retrospectively – only going forward. However, the new order would have prevented me from doing any further publicity on social media or via links from upcoming posts to the blog post I had already published, since it revealed information the reporting of which newly prohibited – including not just the contemnor’s name, but also the gender of the protected party. I was disconcerted to hear one of the lawyers remark during the hearing that it “wouldn’t take more than a few minutes” to change the blog post – as though my concern might be rooted in the time it would take, rather than in the principle of retrospective reporting restrictions. I am becoming increasingly weary of these issues: a year or two ago I would have raised objections and sent a follow-up email after the judge dismissed what I had to say with the comments she “didn’t need to hear further” from me (honestly, she did!), but I simply fixed the matter and put it down to yet another failure to engage properly with transparency in the Court of Protection. [Update, 7th March 2025: I now regret not addressing this matter in that hearing. Similar issues have arisen twice since then in relation to two different committal proceedings.]