By Celia Kitzinger, 27th August 2024

It’s probably safe to assume – unless you’re told otherwise – that if a Transparency Order prevents you from naming a public body, it’s a mistake. That’s been true of the vast majority of cases we’ve encountered.

But even when it’s a mistake, if it’s in a court Order, the prohibition stands. You can’t just go ahead and name the public body and say, “oh I assumed it was a mistake in the Order”. If the Order says you can’t name a public body, then you can’t name the public body, and our Project won’t publish a blog post that names the public body if the Transparency Order forbids it – however unlikely it is that the judge actually intended to stop us from doing so.

So, you’ll want to get it changed (technically, “varied”) and that means asking the judge.

The simplest way to do this is to send an email to the judge (use the email address of whoever sent the Order), pointing out that the Transparency Order prevents you from naming the public body and asking for this prohibition to be removed. Anyone affected by the Transparency Order has the right to ask for it to be varied. You should quote the wording of the Order and the paragraph number.

Here’s an example of a letter I wrote after receiving the Transparency Order and before the hearing was due to start.

Usually, if the judge gets a letter like this before the hearing starts, he or she will say something to counsel along the lines of: “I have received a letter from X which points out that the Transparency Order prohibits identification of [the local authority/the Trust/the Public Guardian etc]. Unless any of you wants to make a case to me as to why that body should have its identity protected, I propose to vary the Order to remove that restriction”.

My experience is that when this happens lawyers are quite surprised that the Order does protect the identity of a public body, and nobody seeks to argue that it should. The judge then changes the Order.

In this case, though, it turned out that the hearing was then vacated – i.e. it didn’t happen. So the judge didn’t have the opportunity to raise it with the lawyers.

So, I sent a follow-up email pointing out that, even though this hearing wasn’t going ahead, I was still concerned about the Transparency Order since “it will presumably apply to future hearings in this case”. (The same Order is used over and over again, often for years, apparently without anyone ever looking at it again.)

I wasn’t wholly confident that anyone would deal with that email, so I also made a formal application for the Order to be varied (as Senior Judge Hilder advised me in a Court of Protection User Group recently) by completing the standard form (I’ve done dozens now!) called a COP 9. (You can download the blank forms here: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/602a3d8bd3bf7f03208c2b40/cop9-eng.pdf)

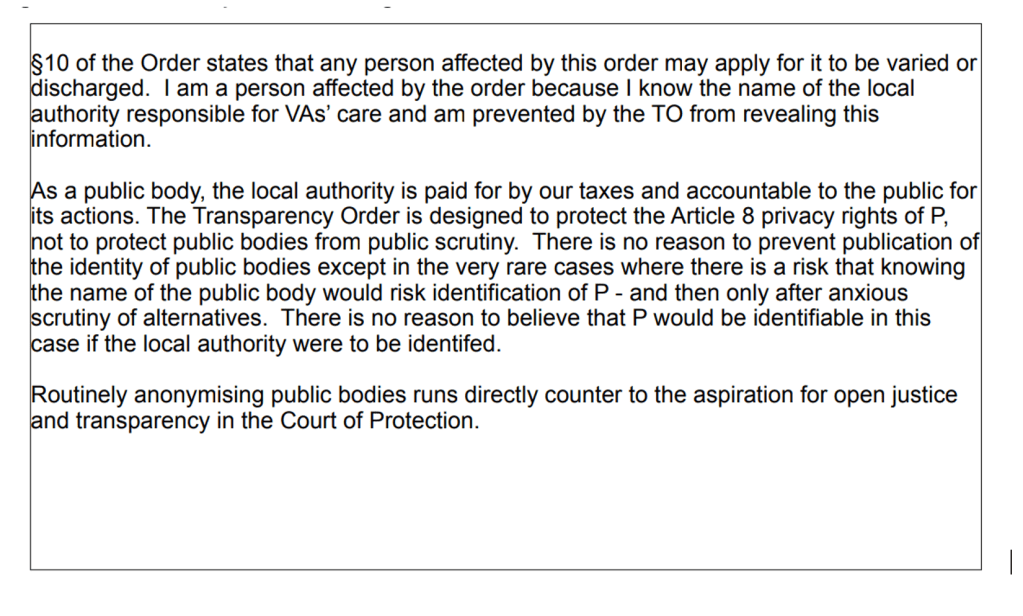

It asks for the case number and the name of the protected party (I wrote “I don’t know. The initials used by the court are VA”) and then my own name and address and contact details. In response to “what is your role in the proceedings” I wrote “public observer”. Asked what order I was seeking from the court, I wrote: “Variation of Transparency Order (made by DJ Hennessy on 3rd April 2024) to permit identification of local authority.” And these were my grounds:

I sent the form to the Manchester address from which I’d received the Transparency Order.

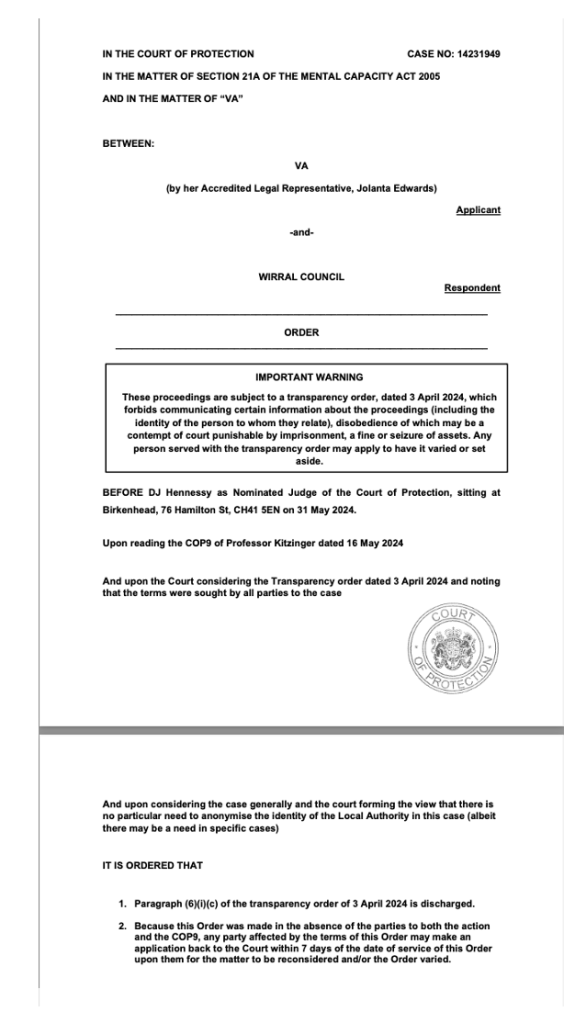

Just over two weeks later, I was sent this (see below) . All sorted!

As you can see, the Local Authority I’d been forbidden to name was Wirral Council, but I don’t think anybody intended to prevent me from naming them – and nobody has notified me of any subsequent application as per [2] in in Order above. So that’s done.

How to identify a problem with the Transparency Order

Obviously, it would be best if the court got the Order right in the first place, but when it doesn’t, it’s good to see a judge being responsive and supporting open justice like this. It was exemplary behaviour – and rather a contrast with what happened in another case I wrote about here: “Prohibition on identifying public guardian is ‘mistake not conspiracy’, says judge”.

Judges do make mistakes, and it would support open justice in the Court of Protection if everyone who is sent a Transparency Order could rapidly identify if there’s a problem (e.g. because it prohibits identification of a public body) and if there is, raised the matter with the court.

It helps to be able to identify, quickly, what the Transparency Order prevents you from doing.

Here’s how.

When you get a Transparency Order, it’s almost always in the ‘standard’ form, i.e. following the 2017 template which you can see, in advance, here: https://www.judiciary.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/cop-transparency-template-order-for-2017-rules.pdf

The relevant paragraph is called “The subject matter of the Injunction”. In the template it’s §6, and you could start by going straight to §6 of the actual Transparency Order you’ve been sent, but sometimes the numbering is different so if §6 doesn’t say “The subject matter of the Injunction” look at the paragraph before and after. It’s essentially a list of the persons (and organisations) you’re not allowed to identify.

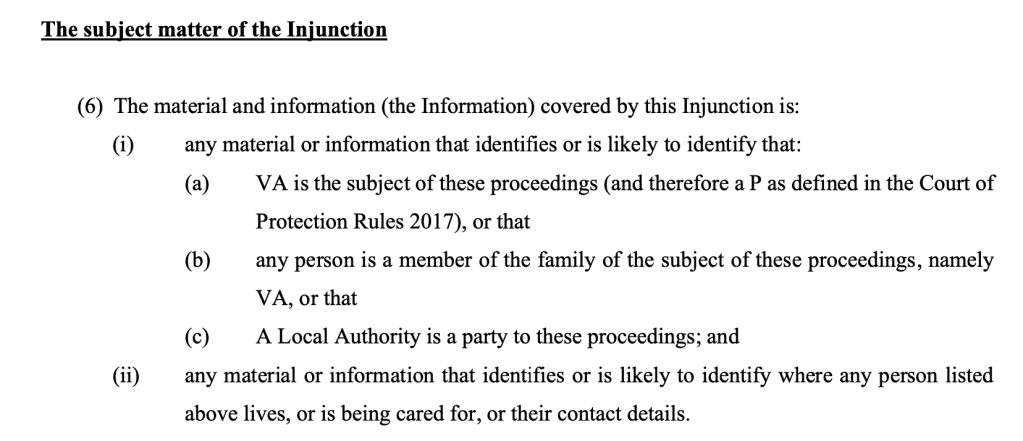

Generally, §6(i)(a) says you’re not allowed to identify the person at the centre of the case (“P”). Then §6(i) (b) says you’re not allowed to identify any member of their family. It’s after those two prohibitions – as §6(i) (c) and (d) etc. that you may sometimes find a prohibition on identifying other people (e.g. a treating clinician, or the manager of a care home) and then a prohibition on identifying a public body. And that’s the prohibition you should ask the court to vary. This is what the one I was asking about looked like – and the problem was (6)(i)(c)

If you get a Transparently Order that has a clause in it like (6)(i)(c) – it might say “A Local Authority” (as above) or it might say the Trust or Health Board or the ICB, or th Public Guardian, or the Official Solicitor – you should ask the judge whether this is really what is intended.

Sometimes (very rarely) there’s a good reason for requiring us to keep secret the name of a public body. For example, if P is being treated for a rare condition in a small Trust which has only one hospital at which she could plausibly be treated – so identifying the Trust risks identifying P. If that’s the case, the court can explain it to you. But in my experience, that’s really unusual. It’s much more likely to be a mistake.

The Court of Protection judiciary has repeatedly stated its aspiration to transparency. These mistakes prevent the judiciary from achieving that aspiration. That’s why it’s so important that we all assist the court by pointing out their mistakes – and in doing so we make small but significant strides towards an open and accountable system of justice.

Celia Kitzinger is co-director of the Open Justice Court of Protection Project. She has observed more than 560 hearings since May 2020 and written more than 100 blog posts. She is on LinkedIn (here), and also on X (@KitzingerCelia) and Bluesky (@kitzingercelia.bsky.social)