By Celia Kitzinger, 16th October 2024 (updated 21st October 2024)

It seems unlikely that the court has the power to require me to report information dictated to me by the judge, or to use specific words, as a condition of publication – but where is it written down that’s so?

When I asked around, lawyers told me that it’s so obvious that judges can’t mandate reporting in this way as to need no authority to back it up. The best I could find was Poole J stating clearly that “The court cannot dictate the detail of what reporters write or broadcast” (§20(vi) Re BR and others (Transparency Order: Finding of Fact Hearing) – although it is clear from the judgment as a whole that his focus is on reporting restrictions and do not also encompass, as in the case I’m reporting on here, the court dictating that certain things should be said. Perhaps it’s never occurred to anyone that a judge would mandate reporting of particular information? But a judge has.

In response to my emailed request to report on part of a private hearing before DJ Bland, the judge gave me permission to publish conditional upon the inclusion of particular information and on the use of specific words in my report.

‘The court gives permission asked for in paragraphs 1 & 2 on condition that […] the family members are referred to as “they/them” instead of [xxxxxxxx the redacted words are conventional gendered pronouns]…. any publication should record that there was no formal application made by any party to convert the proceedings from private to public, save for there being a short discussion at the beginning of the hearing’

(Email from Lancaster Family Court, 11th Sep 2024 at 10:37)

I’ve never been sent anything like this before. I experience it as interference with my freedom of expression and with the Project’s editorial independence.

I object to the judge’s instructions about how I should report this case on principle. I don’t think a judge should tell me what to write. I also object on two specific grounds (further explored in section 5 of this report).

- In my view it’s misleading to report (as I am required to) that “there was no formal application made by any party to convert the proceedings from private to public, save for there being a short discussion at the beginning of the hearing“.

- Use of the pronoun “they” for an individual person can imply a trans or non-binary identity. No such identity was apparent for either of the family members in this case – both of whom used gender-specific pronouns to refer to each other, so the judge is requiring me to use non-preferred pronouns for these people.

I’m also not at all sure that it is within the judge’s power to make this Order (if it is an Order). But I’m not a lawyer – and I’ve delayed writing and publishing this blog post while I researched the matter.

Reporting of private proceedings is banned except insofar as the judge gives permission for any such reporting, in accordance with the Court of Protection Rules 2017. Section 4 – which says that the court can make contempt of court orders relating to communication about private proceedings “on such terms as it thinks fit” (§4.2(4)).

The Rules provide some (non-exhaustive) examples of the sorts of orders this could cover – all of them prohibitions on the publication of certain information, and s.4(d) says that the judge can “impose such other restrictions on the publication of information relating to the proceedings as the court may specify”. Practice Direction 4A likewise says that the court has the power to “restrict or prohibit the publication of information about a private or public hearing” (§1(d)).

So, it’s possible, with a literal reading of the Rules and Practice Direction, that the judge is entitled to impose a restriction on me to the effect that I can only publish the information I want to report if I also publish the information (and use the pronouns) he wants me to report – because the court can do “as it thinks fit”.

I’m not sure, though, that it would have been envisaged by those who produced these documents that a judge would think it fit to require publication of certain information as a condition of publishing other information. Both the Rules and the Practice Directions refer to “restricting and prohibiting” publication: neither suggests that a judge might conditionally mandate publication. It seems an odd thing to do. I can’t see that publishing the information the judge says I “should” publish is necessary to protect anyone’s identity or to ensure the just outcome of the case. I don’t know why I’ve been ordered to do this – or why the judge “thinks fit” to make this Order.

The outcome of my enquiries is that I am not going to risk disobeying what (in the view of some of my contacts) is an “Order” from the court. The advice I’ve received is that if I didn’t include the information above in a published blog about the case, and if I didn’t refer to each individual family member as “they”, I would risk being in contempt of court. Even if the judge is over-reaching his powers in making this Order, I would need successfully to appeal his decision before the Order could be discharged (and I’ve now missed the 21-day cut-off period for making that appeal).

So, I’m writing a blog post in which I describe what happened and my concerns about this in relation to transparency, while complying with the Order to which I object, in the hope of encouraging others to reflect and opine on what was done, and on what should have been done.

As it happens, the Order that I should include certain information as a condition of publishing anything about this hearing is only one of my concerns about this case.

The judge, DJ Bland, is on the Open Justice Court of Protection Project “Watch List”. That’s a list of judges we try to keep an eye on, because there have been problems in the past with gaining access to, or reporting on, their hearings. Despite our expressions of concern sent to the judge and to HMCTS, these problems have continued and are apparent again in this case before DJ Bland, so this blog covers a range of transparency concerns. The sections are as follows: 1. Listing and access; 2. A private hearing; 3. My request to report on the proceedings; 4. Reporting restrictions; and 5. Mandatory reporting requirements – which addresses the matter of the judge making permission to publish conditional on my saying certain things and using certain words.

1. Listing and access

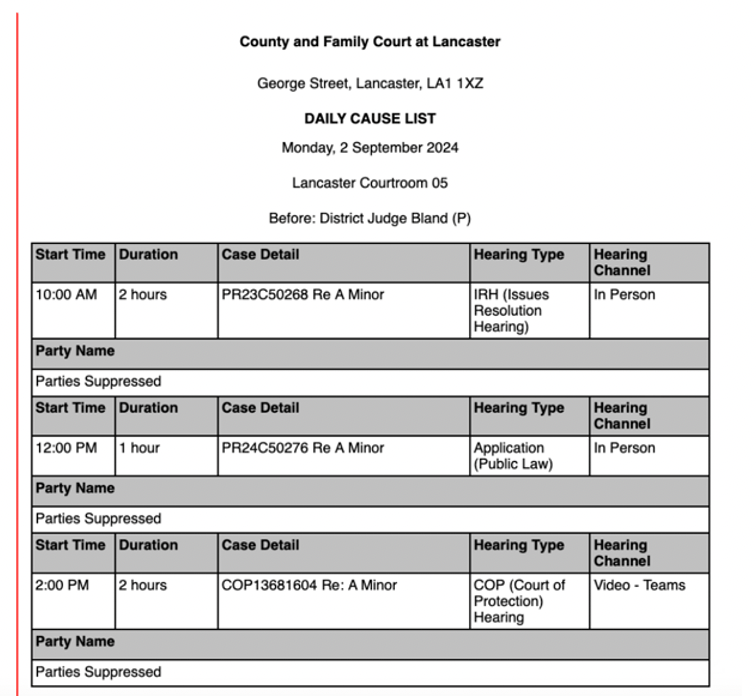

I initially asked to observe this hearing (COP 13681604), without knowing anything about it, simply because it was before a judge on our Watch List (DJ Bland) and because I also noted that it had been wrongly listed (see Courtel/CourtServe listing below – it’ the third one down).

- It appeared only in the Daily Cause List for Lancaster and not in the Court of Protection list which is where it’s supposed to be.

- It doesn’t say anything about the issues before the court.

- It doesn’t say whether it’s private or public.

- There are no contact details provided for would-be observers.

The depressing fact is that these problems recur repeatedly in connection with DJ Bland’s hearings[1].

The listing errors are likely to be outside of the judge’s control, since listing is done by staff employed by His Majesty’s Court and Tribunal Service (HMCTS). But regardless of where the responsibility for the failures lies, the effect is that DJ Bland’s hearings are regularly inaccessible to members of the public.

As I wrote to HMCTS in relation to this hearing, “ Given the odds are stacked against any observer being present, I would like to observe it please. Can you send me the link” (email, 1st September 2024, at 21.21)

I received a prompt reply, giving me the judge’s response: “this is a Public hearing relating to deprivation of liberty in relation to care and residence and that it is an Issues resolution early final hearing, which information is contained on the list displayed to court”. (email, 2nd September 2024, at 09:59)

So, from DJ Bland’s response, I took it that the hearing should have been listed as “Public” – albeit that this information was missing from the publicly available list. This was unsurprising. Around 95% of listed Court of Protection hearings (leaving aside dispute resolution hearings, hearings on the papers, judicial meetings with P and so on) are heard in public – but this fact is sometimes omitted from the public listings and it is common to have hearings erroneously listed as “private”[2].

2. A private hearing

So, although the CourtServe list didn’t say whether this hearing was public or private, the judge assured me, (in the email sent to me that morning at 09:59) that “this is a Public hearing”. It turned out he was wrong about that.

Judges sometimes don’t know whether their own hearings are “public” or “private” because the distinction sometimes turns on whether or not they have made a Transparency Order (which in turn depends on the lawyers having prepared a draft Transparency Order and put it in front of the judge to approve). That seems not to have happened in this case. As far as I can tell from what happened in court, the hearing was “private” by default (for lack of a Transparency Order) and not because the judge had at any point made an Order to say that the hearing should be private. In fact, there didn’t seem any reason why it should be, and nobody argued that it should.

Shortly after I joined I video-platform, and before the judge entered, one of the lawyers (Hannah Haines, joint head of the Court of Protection team at Nine St John Street – and also herself a Court of Protection Tier 1 judge and a part-time Mental Health judge) explained to staff that the proceedings were currently private. There was no Transparency Order.

When the judge joined at 14.16 (after a delay occasioned by connection problems for family members) he announced that an observer had joined the hearing and asked if there were any objections. There were not.

On the basis of submissions from the parties, none of whom opposed the hearing being

made public, I expected the judge to confirm that the hearing would be public. He did not.

He gave a brief judgment stating that “on balance it is not appropriate to convert the proceedings to a public hearing” but that he would “allow Ms Kitzinger to observe the hearing, without being able to report anything”.

And with that the substantive proceedings began.

The judge’s reasons for deciding to hear this case in private (albeit with me present as an observer) were not clear from his judgment. Neither he nor the advocates in court offered any Article 8/Article 10 analysis of the issue.

3. My emailed request to report on the proceedings

Since, in his oral judgment, the judge had specifically banned me from reporting anything at all, I wrote to the judge after the hearing seeking permission to report on part of the proceedings – “specifically, that part of the hearing where you sought the parties’ position on whether the hearing should be held in public or in private (and if in private whether they were content for an observer to attend) – plus your judgment on the matter”.

I explained: “This is because I am writing a piece about how judicial decisions are made to hear matters in private. I have attended about two dozen hearings at which judges have dealt with applications – usually for hearings to be private – and about 50% of the subsequent hearings have in fact been held in private (and I’ve usually been excluded at the point that decision is made). This is of obvious public interest and a crucial matter for understanding the way in which open justice and transparency operates in the Court of Protection. I would add that it is my experience that the submissions (and judgment) as to whether or not a hearing should be (or continue) in private is often held in public and I can normally report on it (subject to a transparency order). I appreciate that is not so in this case.”

I further explained that I wanted to report that proceedings had been going on for a long time, and that ”the family members manifested obvious [XXXXXXXX redacted – an emotional reaction] via [[XXXXXXXX redacted – a behavioural display of emotion] – during the hearing”.

4. Reporting restrictions

The judge’s response was to permit publication subject to conditions which included both reporting restrictions and mandatory reporting requirements.

In my email seeking permission to report on part of the proceedings, I suggested two reporting restrictions: the kinship relation between Relative A and P, and he name and type of placement where P lives. These would have been the restrictions I would have suggested for inclusion in the Transparency Order if I had been given the opportunity to argue that the proceedings should be made public. The judge, in his response, did make these reporting restrictions. He said he gave permission to publish on condition that “any reference to [P’s] name is removed with her being referred to as “P” and that the term “placement” should be used instead of [XXXXXXXX ]” and also required that the kinship relationship between Relative A and P should not be identified. I’m content with all that.

Additionally, though, he prohibited reporting on two other matters: “the report should not refer to anything from the hearing which includes the length of the proceedings and the family members being [XXXXXXXX – the redacted term is an emotional description], as this would be taken out of context”.

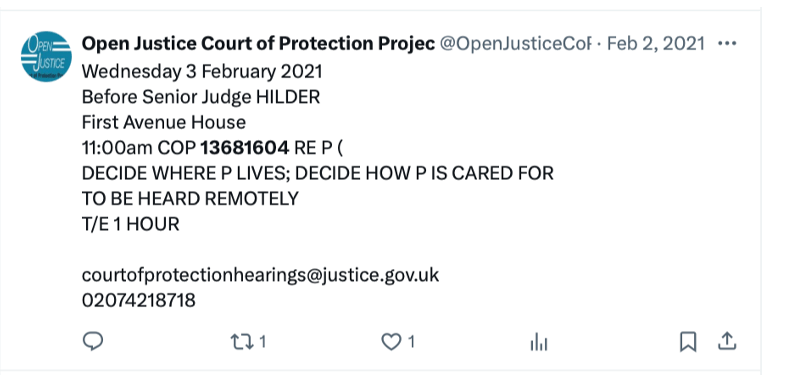

Judges, lawyers and family members frequently comment on the duration of proceedings during the course of hearings (often critically) and we regularly report these comments. The duration of proceedings is of course public information, since the public website, Courtel/CourtServe, publishes lists of hearings (and we reproduce them) informing the public when hearings are happening. It is possible to deduce something about the length of these proceedings from publicly available information – such as this tweet from 2nd February 2021, which show that the case was before Senior Judge Hilder three-and-a-half years ago.

The judge has prohibited me from reporting what was said about the duration of proceedings during the course of this hearing, or people’s views about that. So I won’t report on those matters. Additionally, the judge has banned me from on reporting the family members’ displayed emotional reactions in court. Both restrictions are unprecedented in my experience and the only reason the judge gives for making these reporting restrictions is because “this would be taken out of context”. I’ve never heard this given as a reason for a reporting restriction before. The usual grounds are protecting P’s identity and privacy, or that of the family, or preventing interference with the administration of justice.

I’m not sure what the judge means by “taken out of context”. By me? By readers? And what “context”? Clearly the duration of the proceedings and family members’ emotions are in the “context” of the court proceedings. Admittedly I don’t know very much about these proceedings. Even when I’m provided with an opening summary and Position Statements and even when I’ve been following a hearing over months or years (none of which applies here), the “context” I have for what I see and hear in court is much less than that of the judge, who has a whole bundle. Not knowing enough about the context is always a problem for observers – and I recognise it must sometimes be a problem for judges and lawyers who read our blog posts and form the view that we might have written them differently if we had been privy to more information about the case. But those are the constraints within which transparency in the Court of Protection operates.

5. Mandatory reporting requirements

My primary objection to a judicial edict that I “should” report certain information and use particular pronouns as a condition of publishing anything about the hearing is an in-principle objection. I think this is an interference with my Article 10 freedom of expression rights – and in this case there are no Article 8 privacy rights to balance against them (or none that were raised in court or in subsequent correspondence with the judge).

I also have specific objections in this case to the particular information the judge tells me I “should” report.

First, I believe it would be misleading for readers to rely on the statement the judge says I must include: i.e. that “there was no formal application made by any party to convert the proceedings from private to public, save for there being a short discussion at the beginning of the hearing” (Email, 11th September 2024 at 10:37).

I’ve complied with this condition by quoting the judge’s words, but this is not how I would choose to represent what happened. It is true that no party made an application to convert the proceedings from private to public. It is also true that no party opposed making the proceedings public. Additionally, it was clear that one party (the family member and litigant in person I’ve anonymised as Relative A) would have welcomed publicity – but the judge did not inform this person about the possibility of making an application to convert the proceedings from private to public. Finally, of course, a judge can make proceedings public even if no party asks for this – and indeed, even if a party opposes it (though nobody did).

Here’s what happened.

Submissions were made by Hannah Haines (for the ICB) and by Kerry Smith of Garden Court North Chambers (for the protected party via an Accredited Legal Representative). I report what they said with the usual caveats about accuracy, given that I’m not allowed to record hearings and these quotations, based on contemporaneous touch-typed notes, are unlikely to be 100% verbatim.

“The proceedings are currently private. There is a difference between holding a hearing in private and preventing an observer from attending. An observer can attend a private hearing but no information can be published in respect of those proceedings. The ICB is concerned about some matters if the proceedings were to be made public for the following reasons. First there is a history of safeguarding concerns of a personal nature regarding P. Second, concerning [Relative A] there are more pertinent issues. [Relative A] has indicated a desire to go to the press about [their] views regarding P’s treatment and residence. Proceedings being private make a very clear delineation in terms of no information being published outside of the proceedings. The concern is that if proceedings are public and a Transparency Order is in place, then there is a more nuanced area in terms of identification of P in terms of residence. Geographical area, [location of placement] and other circumstances may make it easy for P to be identified, even if the strict terms of the Transparency Order are not breached. My client is content for you to make a decision and is not going to object to proceedings being made public or to them being kept private.” (Counsel for the ICB)

“The Accredited Legal Representative is neutral – recognising there are competing considerations. There is a matter of proportionality in making a Transparency Order when this is the final hearing and the case has been heard in private until now. We acknowledge the concerns of the ICB. [Relative A] has advocated previously for matters to be public and is here to represent [themself]. [They] wants to shed light on P’s situation and would welcome an independent observer to these proceedings.”(Counsel for P via the ALR)

Relative A was also asked whether they had any objections to my attendance at the hearing and reporting of it and said “No, that’s fine” – though it has to be said that I got the strong impression that their attention was not very much engaged with the matter of my presence in court as there were other burning issues very much at the forefront of their mind.

So – no party objected either to my presence as an observer in a private hearing, or to making the hearing public.

It seemed likely that in fact Relative A would have supported my application (or even made one of their own) if they had understood what was going on – as indicated by Counsel for P via the ALR.

The “concerns” raised by Counsel for the ICB relating to the identification of P on the basis of jigsaw identification from reporting about the geographical area of the case seemed to me to be both unlikely to materialise in reality and also as readily solvable with simple amendments to the standard Transparency Order. Nothing I heard later in the hearing changed that view. There was nothing to indicate that this hearing was in any way more challenging for transparency than many other cases which are routinely heard in public.

My opinion wasn’t sought – but if I had been offered the opportunity to speak (the judge is of course under no obligation to permit a member of the public to address him in court), I would have asked for the hearing to be made public and suggested ways of drafting a Transparency Order (e.g. with some minimal restrictions relating to place of residence) to avoid the (remote) risk of P being identified as outlined by counsel for the ICB.

Second, I have also been required – again as a condition of reporting – to refer to individual family members (who identify themselves in conventionally gendered terms) as “they”. In the context of contemporary gender politics, this is simply offensive. I could have written about them without revealing their sex/gender if required to do so (and without using “they”) but the judge specifically required me to use “they”. I suspect he is unaware of the political issues at stake and that this was merely an attempt to provide an additional layer of anonymity. The Open Justice Court of Protection Project guidance for bloggers (available for download here) specifically advises against this strategy for anonymising people. The Equal Treatment Benchbook (Chapter 12) advises judges to use people’s preferred pronouns where possible, and this judge did so in court. A blogger should not be compelled by judicial edict to refer to a person customarily referred to as “she/her” or “he/him” as “they” implying a non-existent trans or non-binary identity and departing from that person’s preferred pronoun use.

So, to return to my opening question and the title of this blog post: Can the court require certain information to be reported and specific words to be used as a condition of publication about proceedings? Or is this judge over-reaching his authority? Does the judiciary need more training on transparency? Should I have appealed – and what might have happened if I had? And what are the implications of decisions like this for transparency and open justice in the Court of Protection? I’m also wondering whether DJ Bland’s order (if it is an order) is “ultra vires” – i.e. it wasn’t within his power to make it: if that’s so I would have a defence for breaching it, but it’s not something I want to risk.

Finally, the end result of holding the proceedings in private, and restricting/mandating my reporting of the case, is that I’m not able to write anything about the substantive issues. They were interesting, and concerning, and raised some problems relating to litigants in person and family members’ involvement in Court of Protection proceedings. I would have liked to report on the substantive issues – and the litigant in person, Relative A, would have no doubt welcomed the publicity. But that hasn’t happened due to the judicial decisions relating to transparency in this case. Transparency is clearly the loser.

Celia Kitzinger is co-director of the Open Justice Court of Protection Project. She has observed more than 560 hearings since May 2020 and written more than 100 blog posts. She is on LinkedIn (here), and also on X (@KitzingerCelia) and Bluesky @kitzingercelia.bsky.social)

[1] See Amanda Hill “Apologies for any inconvenience caused”: A failure of open justice, 29th February 2024 and Celia Kitzinger Just another failure of open justice: DJ Bland in Lancaster County Court, 11th July 2023. It happened again in 7th October 2024. We are missing many of the DJ Bland’s hearings because they are incorrectly listed. Additionally, for months at the beginning of this year, the contact telephone number for the North West Regional hub (the contact for DJ Bland’s hearings – as well of course as a lot of other hearings in the Manchester area) was wrong: it went through not to the Court of Protection but to Adoptions. It took multiple emails from us to correct this, and it was wrong again for some hearings in October 2024. And in February this year, an observer was denied access due to the court’s “internet problems”.

[2] See: “Private” Hearings: An Audit. Recently HHJ Cronin (COP 13683207, 26 September 2024) read out in court the listing as it appeared in her own list, demonstrating that all the information that should have been (and wasn’t) in the Courtel/CourtServe listing was in fact in the list provided by the court. Something is going wrong, it seems, when HMCTS court staff enter the data into Courtel/CourtServe – and it is very much to the detriment of open justice, and must be very frustrating for judges for whom this is an important aspiration.