By Celia Kitzinger, 9th March 2025

This is an expanded and updated version of part of the submission I made on behalf of the Open Justice Court of Protection Project to the Ministry of Justice Law Commission Consultation on contempt of court. I plan to publish the other parts of my submission in a separate blog post. The consultation closed on 29 November 2024 (although a supplementary consultation not germane to the matters raised in this submission was subsequently launched). There is more information about the Ministry of Justice consultation (click here), and their consultation paper can be downloaded here: Ministry of Justice Contempt of Court Consultation Paper.

The proposals put forward in the Ministry of Justice Contempt of Court Consultation Paper involve four broad lines of reform, the second of which is described as “a move towards transparency and accountability”. In my view, the suggestions on this front do not go nearly far enough and do not address the practical barriers to transparency and accountability as they (repeatedly) manifest in the Court of Protection.

In my response to this aspect of the Consultation Paper, I draw on the experience of the Open Justice Court of Protection Project to document the extent to which the court – in practice – fails to ensure that contempt of court proceedings are transparent. In practice, the conduct of these proceedings often fails to comply either with the (updated) Lord Chief Justice’s Practice Direction on committal for contempt of court or with recent guidance in case law, notably the guidance in Esper v NHS NW London ICB [2023] EWCOP 29, in which Poole J offers a thorough review of the rules around contempt and transparency – including the interplay of different regulations. In addition, I suggest the rules and guidance need developing to further support transparency, in ways that go beyond the proposals in the Consultation Paper.

This blog post has five sections:

(1) Non-publication of contempt of court judgments

(2) Lack of comprehensive data about contempt proceedings

(3) Recurrent listing failures

(4) Access difficulties for members of the public both in obtaining remote links and in locating courtrooms in physical buildings where contempt of court hearings are taking place in person

(5) Derogations from transparency to protect P’s identity without appropriately or transparently balancing Article 8 with Article 10.

It seems unlikely that these problems are unique to the Court of Protection: they certainly extend to the Family Court as well. In the text box below, the (then) Press Association journalist Brian Farmer sets out his experience of seven contempt of court hearings over a seven-week period at the end of 2022 and beginning of 2023 in the Court of Protection and in the Family Court.

As I’ll document below, there’s been repeated failure to apply the proper procedures in relation to contempt hearings throughout the time that I’ve been intensively observing Court of Protection hearings (so, since early 2020), and this has persisted over the course of 2024 and into 2025 despite the Esper judgment and the various summaries of its recommendations (e.g. the useful summary in the Court of Protection Handbook, by Alex Ruck Keene KC, albeit written in in language most likely to be best appreciated by legal professionals, here). My experience is that, no, with some notable exceptions, contempt of court proceedings in the Court of Protection rarely meet even the minimum qualifications for ‘transparency’.

1. Non-publication of judgments

Judgments from contempt hearings in the Court of Protection are very commonly not published at all – or not published in a timely fashion or not published anywhere I find it possible to locate them. In my view, judgments should all be published – and published swiftly – on The National Archives and BAILLI (and not solely on the judiciary.uk website where they are difficult to find and seem not to be permanent).

In one case, a custodial sentence of 168 days was handed down on 9 December 2024 (I watched the hearing) but no judgment was published – that I could find – until early March, by which time the contemnor had served five weeks of her prison sentence (ICB v Sophia Hindley [2024] EWCOP 79 (T2)). The judge had alerted me to the likelihood of delay due to challenges with transcribing services over the Christmas period, but I was personally sent transcripts of the judgments many weeks before publication. There are other cases (described below) – at least one of which I am fairly confident concerns a custodial sentence – which have still not been published months or years after judgment was handed down.

My understanding is that judges in the Court of Protection don’t have to publish judgments in contempt proceedings unless they make an order to send someone to prison. That’s what it says in Practice Direction 21A: Contempt of Court which specifies that the relevant rule on publication of judgments “does not require the court to publish a transcript of every judgment, but only in a case where the court makes an order for committal“.

The Consultation Paper proposes that publication should be required in all cases resulting in custodial sentences – whether immediate or suspended. This seems already to be a requirement in the Court of Protection and is self-evidently an important part of transparency in the court. People should not be sentenced to prison without a published record of the reasons.

In my view, the requirement to publish judgments should extend to cover those judgments that do not lead to custodial sentences as well as those that do, not least since custodial sentences are likely to become less common if the Ministry of Justice proposals for alternative sanctions (as described in the Consultation Paper) are implemented. Moreover, it is the threat of a custodial sentence (whether or not one is actually imposed) that does a lot of the ‘heavy lifting’ in these cases. People should not face the risk of being sentenced to prison without a published record of the reasons – whatever the eventual sanction imposed, and even (as in Esper) in the absence of any sanctions.

I suggest that publication of judgments (or orders/declarations – whatever marks the outcome or ‘final decision’ in relation to a case) should be required in relation to all committal hearings – including those where a defendant is not found to have breached court orders, those where a non-custodial penalty (or no penalty at all) is applied, and those that are abandoned. Contempt of court hearings represent a very small proportion of Court of Protection hearings (lawyers keep telling me they are “rare”), so this should not be an onerous requirement.

Contempt of court is a matter of legitimate public interest and these hearings are hugely important for public understanding of the authority of the court and what happens when we disobey its orders. The public should not have to rely solely on the reports of journalists and members of the public for their understanding of these matters. Both public reporting and public understanding would be greatly improved by the provision of authoritative published judgments or formal records of judicial decisions. Lawyers would find judgments useful too. Given the level of confusion and misunderstanding that currently prevails among legal professionals (including some judges), publication of all judgments and ‘final decisions’ in committal cases would also help to safeguard and enhance the administration of justice.

Here are two examples of committal cases I’ve observed for which there’s no published judgment – and no legal requirement to publish one. In both cases I believe publication is in the public interest, and would support understanding of contempt of court procedures for the public and for legal professionals alike.

Norfolk County Council v Caroline Grady (unpublished) is the only case I’m aware of from the Court of Protection where a penalty was imposed in the form of a fine rather than a custodial sentence. Since it’s not published (though I have read the unpublished judgment), the reasons for imposing a fine for contempt of court are not publicly available. The unpublished judgment refers to two arguments that are often raised in committal hearings and which represented the local authority’s position in this case: that the breaches did not meet the custody thresholds and that it would be contrary to the protected party’s best interests for her relative to be imprisoned. The mitigating factors referred to by the judge in deciding against a custodial sentence include the defendant’s admission of contempt on four of the six grounds and an apology for that behaviour. Publication of the full judgment in this case would provide a helpful public record of judicial reasoning in relation to non-custodial penalties for contempt. (UPDATE: We made a formal application for publication of this judgment (see Norfolk County Council v CA & Ors [2025] EWCOP 16 (T3)) and were successful. The judgment is here: Norfolk County Council v CA [2024] EWCOP 64 (T3))

Barnsley Metropolitan Borough Council v DB (unpublished) is a hearing that collapsed due to procedural defects that were spelled out in the judge’s decision to “strike out and dismiss” the application to bring contempt of court proceedings against DB. I don’t have a formal record of this decision from the court and have relied on my contemporaneous touch-typed notes from the hearing to capture the judge’s decision. (There’s more information in my blog post about the case here: Committal hearing: Struck out and dismissed for procedural defects). This is what the judge said:

“Firstly, Rule 21.8(5) states that the defendant’s name will appear on the court list unless the court makes a rule that their name should not appear. I have for the first time this morning had the opportunity to read Esper (Esper v NHS NW London ICB (Appeal : Anonymity in Committal Proceedings)[2023] EWCOP 29). The defendant has never been informed of his right to have rule 21.8(5) considered, or to make any representations about that. It may be that if an application were made, there would be no merit to it, but I have not considered the merits of it. The procedural irregularity is that he’s not had that opportunity.

Secondly, the form that purports to be the application for the committal is wrong. The local authority has not lodged a COP 9. They have borrowed a form, M600 from another jurisdiction. It is the wrong form.

Thirdly, this court directed the defendant should be personally served with a notice of contempt by 19 January 2023, setting out the evidence relied on by the local authority, with a separate list of allegations numbered and identified separately to make it clear what it was being said he’d done, and when, and why it breached the order. This was not done by 19th January, and no application to extend the time was ever made. It was filed and served on Tuesday this week, less than 24 hours ago. The notice of contempt filed on Tuesday has information presented in a manner which I consider to be confusing, using an “and/or” format which is insufficient to enable someone to identify which order they breached and when.

Finally DB has not participated in the proceedings but at no point has there been any consideration of a summons.

I have considered all of those defects and have had regard to Rule 20 of the Court of Protection Rules on appeals which states “The appeal judge shall allow an appeal where the decision of the first instance judge was […] unjust, because of a serious procedural or other irregularity in the proceedings before the first instance judge” (§20.14(3)(b)). I am satisfied there are procedural irregularities and any decision I may made is likely to be successful on appeal, so I am going to strike out and dismiss this application for its procedural defects. I am aware I can waive defects if I am satisfied this would cause no injustice, but I am not so satisfied. I therefore dismiss the application that is before me today.

I do not criticise parties for those defects in a context where there is, in my view, a need – an urgent need – for committal templates in the Court of Protection. Without them, the parties and the court are challenged by everyone’s best endeavour to comply with the rules. Clear templates are need to assist everyone.

Barnsley Metropolitan Borough Council v DB (unpublished) Note: This is not an official court transcript

It might have been useful to the Ministry of Justice consultation exercise on contempt of court if this decision had been published other than in my blog post. The judge raises important points – and in my experience procedural defects are very common in committal hearings (though often waived by judges). Procedural deficits might be averted if more lawyers were aware of the proper procedures.

Publication of judgments should be timely if they are to make an effective contribution to transparency. Here are two examples where they were not (in addition to the concern raised earlier). I’ve referenced these two cases with the judges’ names and case numbers because both were wrongly listed (as described in section 3 below) and did not include the names of applicants and defendants (though I have since been provided with some of this information).

- HHJ Searle (Exeter) COP 12991351 This case concerns a contemnor who – the court tells me – can be named as “Tia Bench” and it seems there is an intention to publish a judgment. I was told by HMCTS staff: “the name of the person with the committal hearing 12991351 is Tia Bench and Her Honour Judge Searle’s judgment for the Committal hearing of 28 June 2023 will be published in accordance with the rules”. That was 19 months ago. I’ve received no replies to my multiple requests in late July and August 2023, or to my renewed enquiries in early 2025 (copied to senior HMCTS staff) in anticipation of writing this report. I’ve not been sent the judgment and I’ve been unable to locate a published version on any of the usual websites. I don’t know what orders Tia Bench is alleged to have breached, or why, or what penalties were imposed, or whether she’s purged her contempt, or appealed, or even whether she is serving a prison sentence. (See the update on this case in the Postscript, added 10th March 2025)

- DJ Taylor (Truro) COP 14097158 I asked for a link to observe this hearing which was listed as committal hearing, in public, for 25 October 2024. I was told it had been vacated. I raised a concern with the listing (it was not compliant with the Practice Direction) and asked for the names of applicant and defendant: I was told Cornwall County Council v. David Orange. I then asked for the judgment and was told it “will be transcribed” and “published through the appropriate channels”. Having subsequently chased this, I received a response on 28 February 2025 (so four months later) to the effect that the transcript has not yet been received, but that it would be sent on to me when it arrived with HMCTS. Concerned that Mr Orange may have been given a prison sentence that members of the public don’t yet know anything about – so effectively jailed in secret – I replied asking to know whether a finding of contempt was made and if so what the penalty was. So far, no reply.

I suspect that the delay in publishing judgments in these two cases is due to administrative issues and general muddle and confusion: “cock-up, not conspiracy” as I am regularly told. It may also have been caused by uncertainty and anxiety about the legal requirements, e.g. whether a member of the public must (or alternatively may) be given the information and on what basis – especially if the outcome for either Tia Bench or David Orange was something other than a prison sentence (I’ve not been told one way or the other). I recognise that efforts to achieve transparency via publication of judgments add to the burden of just trying to keep the justice system functioning in the context of chronic under-resourcing. Nonetheless, whatever the reasons, the judgments have not been published, and I don’t know anything substantive about these two contempt of court cases – resulting in a derogation from transparency, a principle to which (as I’m also regularly told) the judiciary aspire.

One further example of failure to publish judgments in a timely fashion relates to appeals. It is an extraordinary disheartening experience to attend appeal hearings as a public observer, only to be told that the “public” judgment being appealed is not yet published and not yet approved by the judge and so cannot yet be released to observers: this has happened to me several times both in the High Court and in the Court of Appeal (and I’ve seen judges in the Court of Appeal raise their own concerns about how close to the time of the hearing they sometimes receive transcript of judgments). Obviously, if a judgment is being appealed in open court, the public should have timely access to that judgment so that we can properly understand the basis of the appeal and the arguments being made for and against it.

Judgments reporting on ‘final decisions’ (including but not limited to custodial sentences) should in my view be published as rapidly as possible. I would also like to see publication of more of the judgments made over the months or years preceding those final decisions. I am not sure what position the judiciary take on the publication of judgments that form part of what are often very extended committal proceedings during which there are (more often than not) many separate hearings, and separate judgments made – all of which could properly be understood as part of the committal process. These include decisions like: fact-finding about breaches; findings relating to contempt; decisions about penalties; judgments relating to subsequent breaches and activation of suspended sentences; decisions relating to applications to adjourn committal hearings or to appeal findings or decisions; appeal hearings and applications to purge contempt. Publication of a single judgment on its own can give a partial or even misleading impression of the trajectory and outcome of the case. I’m particularly concerned that – in two separate cases I’m aware of – published judgments report information that was dismissed or criticised as unreliable by the judges in their own oral judgments at subsequent hearings – judgments that the judges concerned have declined to publish.

One exemplary instance of publication of judgments as a case unfolds is the case of James Grundy, heard by DJ Davies (sitting in Derby). There are now several published judgments for this case, covering James Grundy’s sentencing (a suspended 28-day prison sentence) on 22 August 2023; then the raising of questions as to Mr Grundy’s capacity in relation to the injunctive order and/or in relation to conducting the proceedings, and then the eventual finding of capacity and on 29 January 2025 he was sentenced to 28 days in prison (Derbyshire County Council v Grundy [2025] EWCOP 1 (T1; Derbyshire County Council v James Grundy). Given this judge’s excellent track record on transparency, I would expect any appeal to the sentencing decision or application to purge to be properly transparent in terms of listing and publication as well. This series of hearings, and the judgments emerging from them, is one of the few examples of (largely) properly transparent practice in relation to contempt of court hearings. It’s been lauded by legal professionals as “a landmark case in Court of Protection enforcement, setting a rare precedent for committal to prison in contempt cases” (see: “Capacity, Contempt, and Custody: What Lawyers Need to Know from DCC v Grundy”). In fact, it’s far from “rare” that the Court of Protection commits someone to prison (its apparent “rarity” is a notion fostered by non-publication of judgments) but what establishes it as a “rare precedent” (from a District Judge!) is the fact that the judgments are published and the reasoning relating to committal made public. Clearly, legal professionals – as well as member of the public – value this transparency. Other (more senior) judges have a lot to learn from DJ Davies. We need more judgments like these.

2. Lack of comprehensive data

There is no systematic data collection about contempt of court proceedings, and no “Transparency Data”[1] is published in relation to contempt of court in any part of the court system. The Ministry of Justice Contempt of Court Consultation paper (July 2024) reports starkly that “no data is published in relation to contempt” (§7.182).

So, nobody – not the Ministry of Justice, not HMCTS, not the judiciary, not members of the public – has any idea how many people have been subject to contempt proceedings in the Court of Protection in any given year, what their alleged offences were, what the outcome was, or even whether or not they received custodial sentences[2]. This is clearly a problem for a court with aspirations to transparency and should be remedied immediately.

3. Recurrent listing errors

Contempt of court proceedings are not ‘transparent’ if members of the public do not know that they are taking place.

It is our routine experience that daily court listings are neither comprehensive nor reliable. It is common to find Court of Protection listings missing essential information and/or hidden away in the wrong section of Courtel/Courtserve, apparently as a result of “innocent human error” (“Court of Protection listing mishap leaves observers in the dark”). I regularly stumble over hearings that do not appear in the listings at all: when I’m alerted to an upcoming hearing by a party involved in a case, there’s only a 50:50 chance that I’ll be able to locate it in public court lists, and I’ve attended at least a dozen hearings that have never been publicly listed. So have other public observers – as described in this report about a Family Court committal hearing that seems never to have appeared in any public list: “East London Family Court holds ‘secret’ public hearing”.

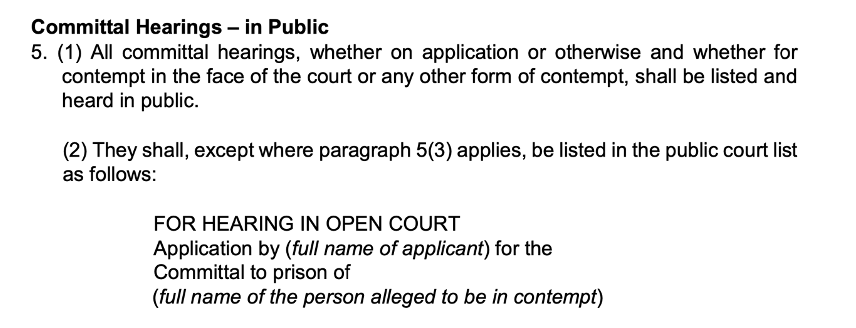

When committal hearings are listed, they rarely comply with the relevant Practice Direction, which requires (except in exceptional circumstances justifying derogation from the general rule of open justice) the following format:

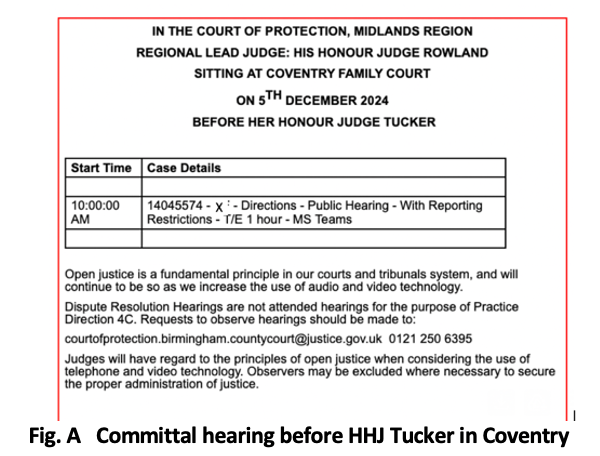

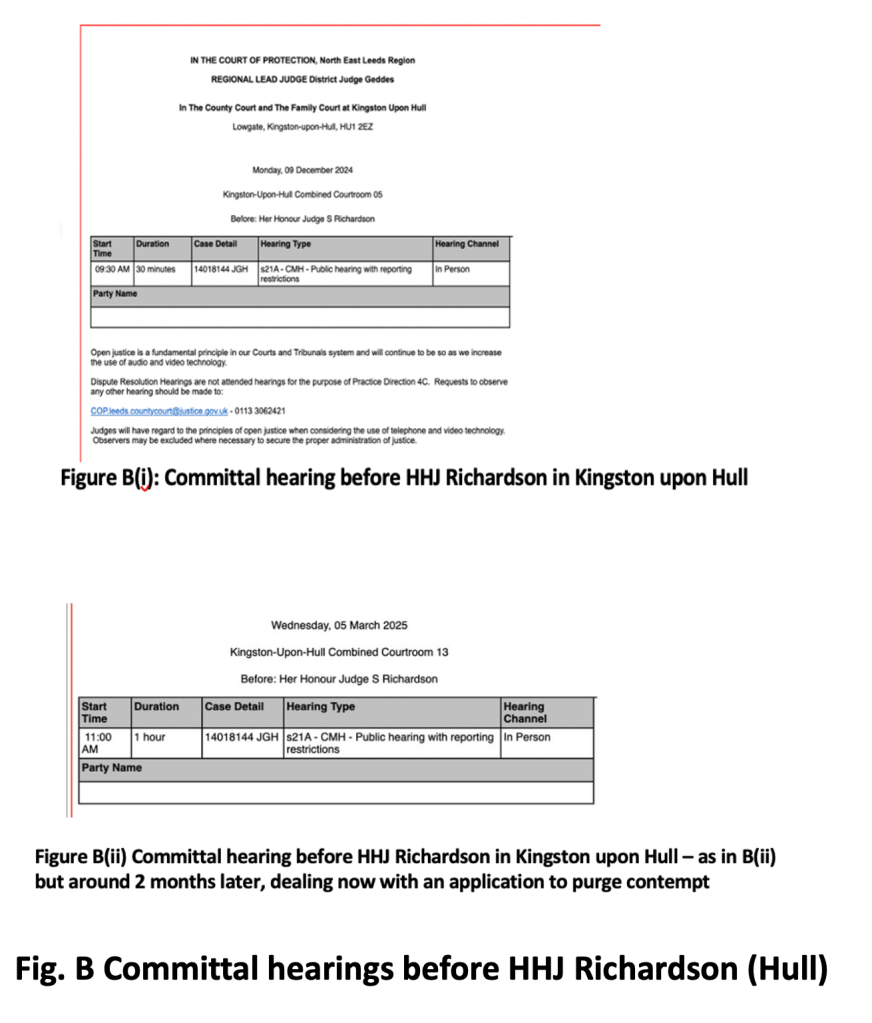

It is in fact RARE to find Court of Protection committal hearings listed in this format. Here is a sample of listings which illustrate how very far normal practice departs from the Practice Direction (see Figures A – H and the explanatory text for each).

- Figure A shows a listing at Coventry Family Court from which it is impossible to know that it is a hearing concerning contempt of court and the possible committal of an alleged contemnor to prison. It doesn’t use any of the required wording: it doesn’t say it’s a committal hearing and doesn’t name either an applicant or an alleged contemnor. I only discovered that’s what it was when I got the link to observe.

- Figure B is composed of two listings for hearings before the same judge in the same case, three months apart. It’s impossible on the basis of the way they’ve been listed – which bears no resemblance at all to the format mandated in the Practice Direction – to recognise that they are dealing with contempt of court. I attended the first of these two hearings (B(i)) remotely. having been alerted to its existence by another member of the public. On being sent unpublished judgments from earlier in the case, I discovered that there had been several earlier committal hearings as well: presumably they, too, had been wrongly listed, so I’d not aware of them and had been unable to observe them, as I would have wished. The hearing in B(i) turned out in fact to be a sentencing hearing at which the judge handed down an immediate custodial sentence of 168 days to one Sophia Hindley, on the application of NHS Humber and North Yorkshire ICB. In written correspondence, I expressed my concern about the way the hearing had been listed. Nonetheless, the next hearing in the case was also incorrectly listed – as a s.21A hearing and not as a committal (see Figure B(ii)). Again, I wouldn’t have known it was a contempt of court hearing had I not been so informed by a member of the public. So, even after drawing a judge’s attention to mistakes in listings – and even with a judge clearly disposed to be supportive of transparency in other ways – those mistakes can persist.

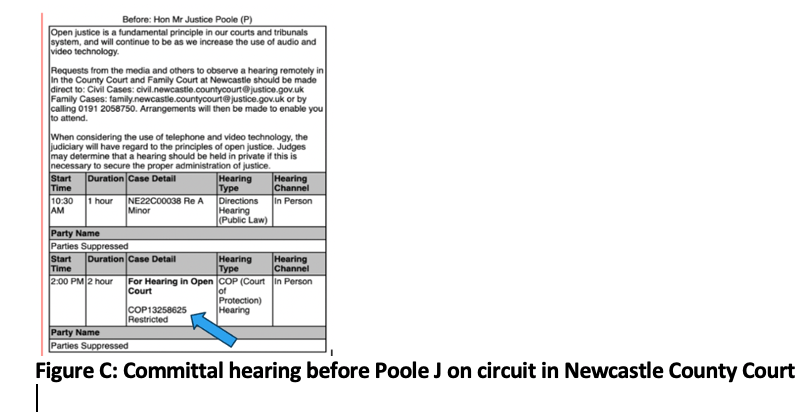

- Figure C is yet another listing for an ‘invisible’ committal hearing, this time before a Tier 3 judge, Poole J, sitting in Newcastle County Court. Again, it is not identified as a committal hearing at all in this list: I only knew that’s what it was because the alleged contemnor (who was subsequently handed a custodial sentence) had told me about it. I understand that the judge had ordered non-disclosure of the defendant’s name. I do not know whether he also ordered that it should not be listed as a “committal” hearings and that the local authority should not be named.

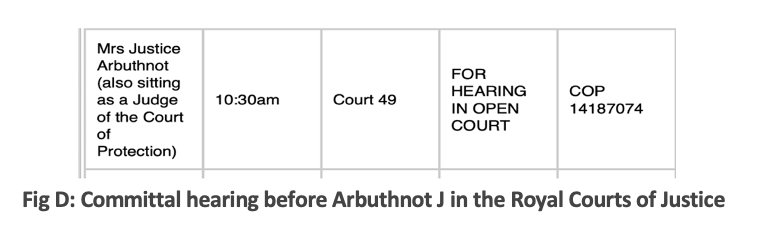

- Figure D shows a committal hearing incorrectly listed by the Royal Courts of Justice. There is no indication at all in Figure D that this is a committal hearing. As in the listings displayed in Figures A to C, the word “committal” is not used and nor are the applicant and defendant named.

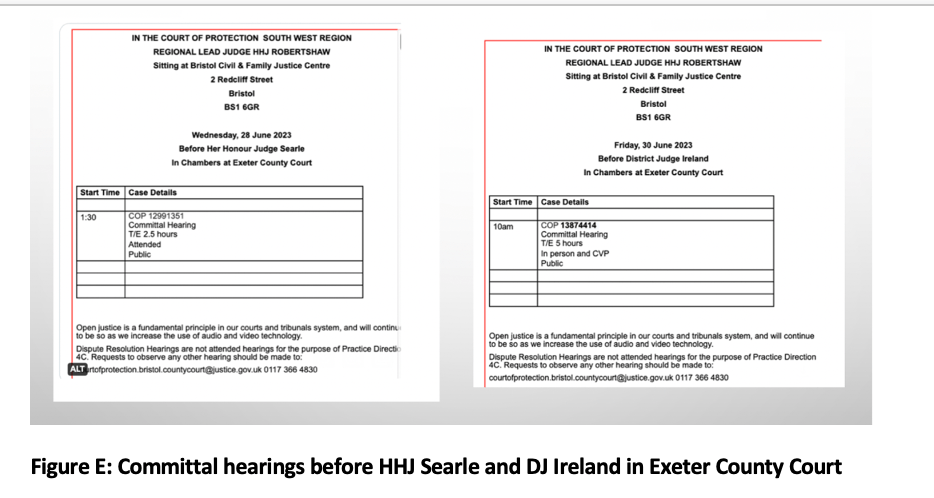

- Figure E below shows two committal hearings listed at Exeter County Court. These two listings improve on those in Figures A-D because they do at least contain the words “Committal Hearing”. However, the hearing before HHJ Searle appeared twice in the listings – in identical form except that the start time was listed as 12.00 in one version and 1.30 in the other (the version displayed below) with no indication of which was correct. Neither of the two versions of HHJ Searle’s case, nor the one before DJ Ireland, provides the name of the applicant or the name of the person alleged to be in contempt. In response to my enquiry about the hearing before DJ Ireland, I was given contradictory information including a one-sentence email to the effect that it was not in fact a committal hearing but a hearing about “capacity” – despite what it says on the listing: I have tried to follow this up with no success. In response to my enquiries about the hearing before HHJ Searle, I was provided on request with the name of the alleged contemnor – which indicates to me that it should in fact have been published on the public listings since it seems there was no judicial order to the contrary. I also received information that the case before HHJ Searle had been correctly listed in accordance with the Practice Direction on the paper version of the list in Exeter County Court.

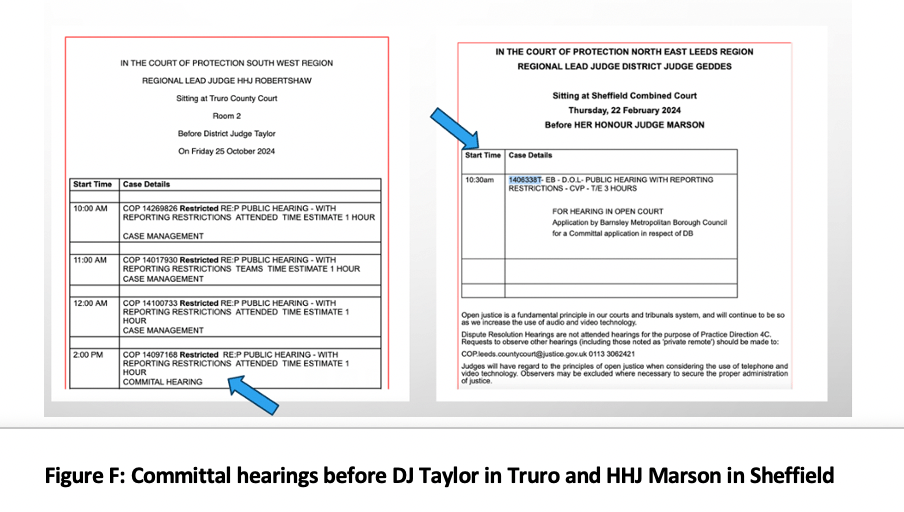

- Figure F shows listings for committal hearings before DJ Taylor in Truro and HHJ Marson in Sheffield. I believe the hearing before DJ Taylor is wrongly listed because it does not name the applicant or the defendant – and I subsequently requested and was told the name of both, leading me to deduce that the judge had not made any exceptional arrangements for applicant or defendant to be anonymised in the listing and that both names should have been on the public listing. As far as I can tell, though, HHJ Marson’s hearing is correctly listed because she had made an order that the defendant’s name should not be listed. I do not know whether she so informed the Press Association about this (as required by the Practice Direction) in advance of the hearing.

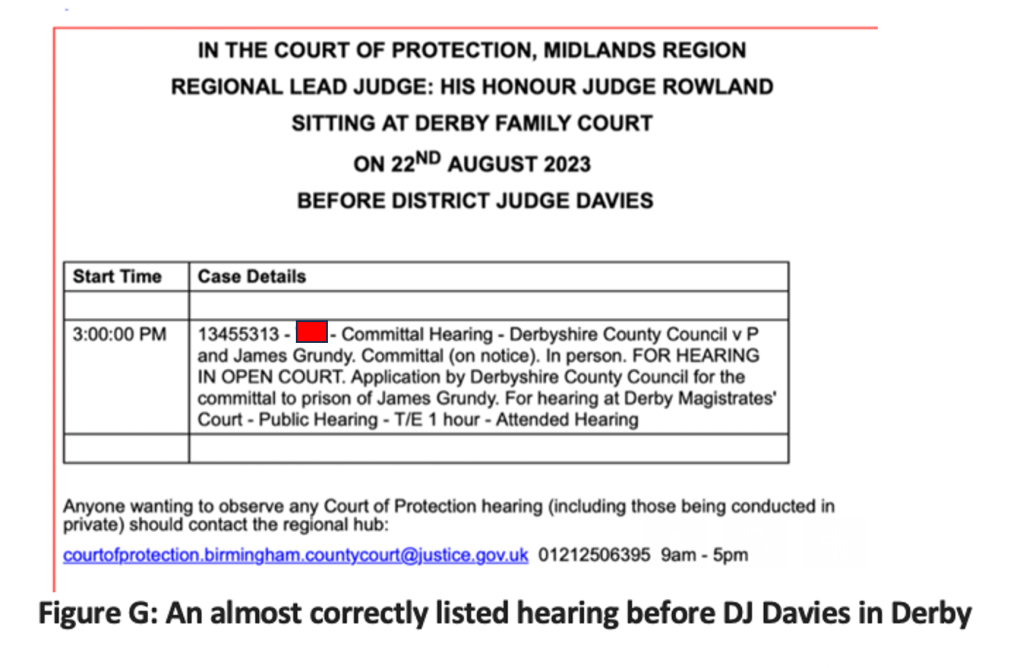

- Figure G shows an almost correctly listed hearing before DJ Davies in Derby. But even with a judge whose commitment to transparency is exemplary and extended to permitting me to observe the in-person attended hearing via video-link, there were problems relating to transparency. At the beginning of the hearing, the judge expressed concerns about the way the listing had appeared on the door of the courtroom (not in accordance with the Practice Direction apparently, although I didn’t see it since I was watching the hearing remotely) and also pointed out that the non-disclosure order had not been served on the Press Association as per the Practice Direction. So, even when judges are fully aware of what the procedure should be, things don’t always go according to plan (see: Committal and sentencing with a possibly incapacitous contemnor). My red sticker in the image below obscures the initials of the protected person which should not have appeared on this listing: she was not a party to the committal application and is referred to as “P” in the published judgments. There is generally no need to use P’s initials in listing a contempt hearing – and it may be inadvisable to do so in terms of protecting their Article 8 privacy rights. The case number provides all that is needed in terms of connecting the committal with proceedings up to that point.

These listing errors are clearly consequential for open justice. They mean we don’t know that committal hearings are taking place, and we don’t know the names of the applicant public bodies or the defendants. Furthermore, the fact that this information is not – as it should be – in the public domain via the lists, has consequences for what happens in hearings because listing errors are often seized upon by parties to advance arguments for suppressing the information that should have been in the listings, wasting a good deal of court time in the process with arguments and counter-arguments that would have been redundant if the proper procedure had been followed such that this information was already in the public domain.

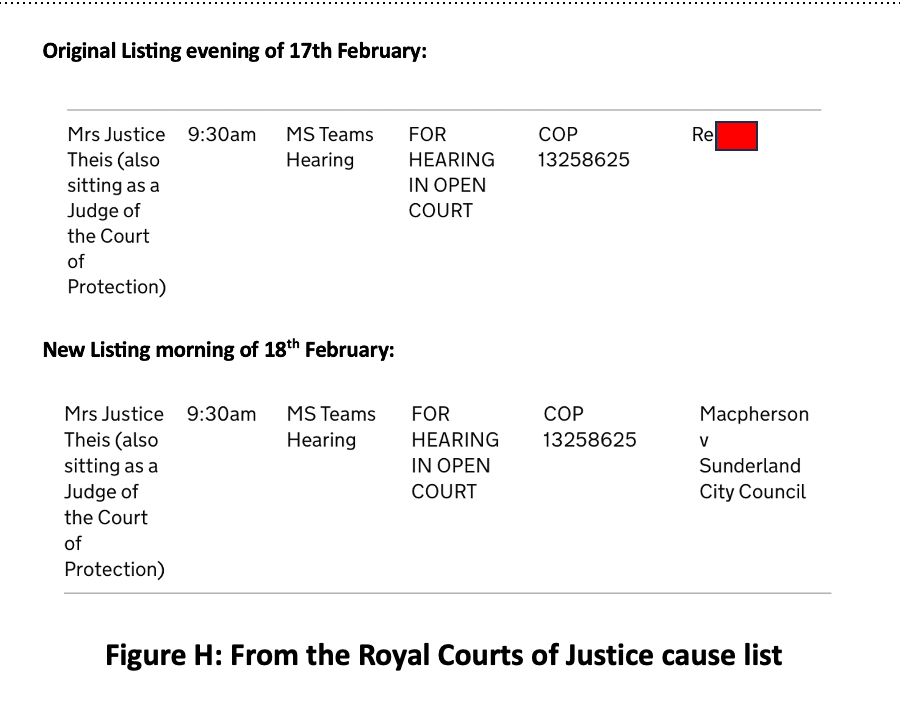

Finally, listing errors for committal hearings also sometimes constitute – in and of themselves – breaches of P’s privacy rights. I’ve seen many times the use of P’s initials (sometimes their real initials) in public lists for committal hearings. One family member said in court she and P were “mortified” by this. Another family member (Luba Macpherson) is – justifiably – angry that her daughter’s initials were used in both in the Court of Appeal list and in subsequent High Court lists in place of the correct naming of the case (i.e. her own name and that of the public body). The red sticker conceals the erroneously printed initials in Figure H below. The defendant has said publicly on social media, that errors like this reek of “hypocrisy” since the courts themselves have risked public identification of her daughter – the very offence for which she has been given a prison sentence.

It’s ironic, in view of the efforts the court undertakes via Transparency Orders to prevent publication of P’s identity by P’s family and by the public, that it should so often publish information prohibited by its own orders: we’ve seen P’s full name on public lists dozens of times, and on a couple of occasions, the names of the care home where they are resident. (We can’t show these, obviously, but we’ve sent some of them, with expressions of concern, to HMCTS staff, and previously published our concern here: A review of transparency and open justice in the Court of Protection ) It’s ironic that P’s name sometimes appears (wrongly) on listings and defendants’ names are (wrongly) omitted; and that P’s initials are used on committal listings where the defendant’s name (and that of the applicant) should be used instead. The work needed on listings clearly goes beyond simply the need to ensure that committal hearings are correctly listed – but what I’ve illustrated in this section is that the lists for committal hearings, in particular, can be very spectacularly wrong.

4. Access difficulties for members of the public both in obtaining remote links and in locating courtrooms in physical buildings where contempt of court hearings are taking place in person

Members of the public regularly experience difficulties in gaining access to Court of Protection hearings: like listing errors, this is not a problem specific to contempt of court hearings. We’ve raised concerns about access issues more broadly in our response to the Transparency and Open Justice Board consultation exercise on key objectives (also published as a blog post here) and we regularly blog about the challenges of trying to get access to observe hearings. These generic access problems impact equally on access to committal hearings.

In brief, public cause lists are published late in the afternoon the day before a hearing, leaving little time for staff to arrange remote access the following day, and making it hard to us to make travel plans to attend in person. I have missed the opportunity to observe some committal hearings because I discovered that they were happening too late to travel to the court; other observers have missed hearings because they were listed as “remote” but were actually held in person, or vice versa.

It can take persistence to gain admission to remote hearings because there are delays in sending the link. In relation to the committal hearing listed in Figure A (above) for a 10am hearing (which at the time I was not even aware was a committal hearing!), I asked for the link the previous evening (19.22 on 4 December 2024), resent the request at 09.19am the following morning, and finally received the link at 10.30am for the 10.00 am hearing, which of course had already started. I gather it started around 15 minutes before I joined. So, a significant proportion of this “public” committal hearing was actually held in private.

Lists in physical court buildings are frequently missing or wrong and staff are sometimes not able to direct us to the right courtrooms. Sometimes, there is no notice on the outside of the courtroom communicating the correct information (in fact, sometimes a notice on the courtroom door even says that proceedings are “private”).

I observed the whole of one in-person committal hearing in Newcastle before Poole J (Figure C above) with some difficulty. There was no public list displayed in Newcastle court showing the committal hearing I’d come to observe, and staff were unable to tell us which courtroom it was in (see: A committal hearing to send P’s mother to prison – and the challenges of an in-person hearing). A journalist seeking to attend another hearing in this same case “… was told by a security guard at the Newcastle Civil and Family Courts Centre that the hearing was a family court matter, was in private, and that he had no right to attend a private family court hearing” (see: “Committal hearings and open justice in the Court of Protection”.

Another member of the public asked for the link to observe a committal hearing before Mr Justice Hayden that was publicly listed as “remote”. On asking for the link, he was told that in fact the court would be sitting in person at 2pm that day, and so he made his way to the Royal Courts of Justice, where the printed list on display still showed a ‘remote’ hearing, which initially stymied the attempts of staff to assist with finding the right courtroom. Eventually – after multiple phone calls and two protracted conversations with staff at different “enquiry desks” – he discovered which courtroom the judge was sitting in, only to find a notice on the courtroom door reading “NO ENTRY TO THE PUBLIC SAVE FOR ACCREDITED PRESS/MEDIA REPRESENTATIVES”. Daniel Cloake is an unusually persistent observer – many others would have given up long before this. He eventually gained entry to this “public” hearing by attracting the attention of the judge’s clerk through the window in the courtroom door, but only eight minutes before the hearing finished. (‘No Entry’ – A committal hearing at the RCJ).

These access difficulties show the real world consequences of listing errors. They effectively prevent members of the public from attending hearings in open court – obviously not limited to, but most certainly including, hearings for contempt of court.

5. Derogations from transparency to protect P’s identity without appropriately or transparently balancing Article 8 with Article 10

According to Nicklin J, Chair of the judiciary’s new Transparency and Open Justice Board, it is a “fundamental component” of open justice that there should be “open reporting“ and “ … that any restrictions imposed by the court preventing (or postponing) reports of proceedings (including anonymity orders) must (1) have a statutory basis … ; and (2) fulfil a legitimate aim, be necessary, proportionate, and convincingly established by clear and cogent evidence”. (Nicklin, J, Newcastle-upon-Tyne Law Society Annual Lecture 2024, 9th May 2024, Newcastle Law School)

In my experience, the reporting restrictions relating to contempt of court hearings are often not (or not transparently) “necessary, proportionate, and convincingly established by clear and cogent evidence”.

Some contempt hearings in the Court of Protection are listed as private – sometimes, it seems, incorrectly due to listing error (a problem in itself) – but others by order of the court because (I was told on one occasion) the judge had decided that this was the best way of protecting P’s identity.

Parties sometimes arrive in the courtroom apparently assuming that the ‘standard’ Transparency Order for Court of Protection hearings that has covered the case up to that point remains in place – and that’s the one I’ve often been sent in advance of the contempt hearing. But the standard order includes the statement that it “does not apply to a public hearing of, or to the listing for hearing of, any application for committal” (9(3)). When I’ve pointed this out, it feels like a last-minute scramble by lawyers unprepared for this eventuality to draft an appropriate order.

The previous order – the one that “does not apply” to the committal application now about to be heard – almost invariably protects P’s identity and that of their family members. It is almost always one of those family members who is now before the court accused of contempt. Lawyers and the judiciary display a protective impulse and are attracted to the idea of a new order which duplicates or extends the existing one – including the prohibition on naming not just P, but also the family member now risking a prison sentence, the defendant. This is not, according to Poole J’s judgment in Esper the correct way to go. The Court of Protection Handbook summarises the situation as follows:

COPR r21.8(5) is not triggered to prevent the disclosure of the identity of the defendant if the sole purpose is to protect the interests of P. It must be the interests of the defendant that need protecting. In the event of a committal order it will be exceptionally rare for the court to find that the r 21.8(5) conditions are met in respect of the defendant. In the event of a finding of no contempt of court, it will be relatively more likely that the court will find that the r 21.8(5) conditions are met in respect of the defendant, but it will still be an exception for the identity of a defendant to committal proceedings not to be disclosed.

Despite this clear guidance, I have listened many times to counsel advancing the argument that publishing the name of the defendant is not in the best interests of P because it risks P becoming publicly identified. Sometimes this argument is advanced as part of a case for prohibiting publication of the name of the defendant. Alternatively, it’s sometimes advanced to point to the increased risk to P created by publicly naming the defendant, and as an invitation to the court to consider what further protection might be needed via enhanced restrictions in the Transparency Order to prevent jigsaw identification.

Protecting P’s right to privacy, and protecting P from harm that might result from public identification, are legitimate aims that have been long been widely accepted as justifications for derogations from open justice in the Court of Protection. That’s why (except in exceptional circumstances) we are routinely prohibited from publishing the names of P and their family members, or their contact details, or anything “likely” to enable them to be publicly identified.

I have never seen an application to name P (during their lifetime) in committal proceedings. I have never made such an application myself and cannot imagine the circumstances under which I would wish to do so.

In the context of committal hearings, in which the contemnor (often P’s family member) is named (which post-Esper seems to be more common), there needs to be a realistic assessment of the risks of this for P. The key issue is not whether naming the defendant increases the theoretical possibility of someone being able to identify P (whose name they are in any case prevented by the Transparency Order from publishing) but whether, in reality, this is “likely”, whether it might cause harm, and what additional safeguards involving derogations from transparency are “necessary, proportionate and convincingly established by clear and cogent evidence“. Essentially, the judge is back in what should be familiar territory (from drafting the previous Transparency Order): she is carrying out an Article 8/Article 10 balancing exercise – but with different law and facts to consider in the new context of committal proceedings and in relation to what is already (or should be, or will be) in the public domain, including, now, the defendant’s name.

Former PA journalist Brian Farmer addresses some pertinent issues relating to the Article 8/Article 10 balance in a letter he wrote to Poole J in response to the judge’s decision, at an early stage in the committal hearing, to withhold the name of the defendant from the public court lists. Brian Farmer and I made an application for the defendant (subsequently identified as Lioubov [Luba] Macpherson) to be publicly identified, along with the applicant (Sunderland City Council). (We did not apply to publish the name of the protected party, her daughter.). Post-Esper I think it’s increasingly clear that naming the defendant is no longer viewed as discretionary (as Poole J saw it then) but must comply with strict tests of necessity – but Brian Farmer’s points about the real world implications of naming a defendant family member and the likelihood of P being publicly identified (or harmed) as a consequence are of continuing relevance.

Extracts from letter from Brian Farmer (then Press Association journalist), to Mr Justice Poole

We would say people have a fundamental right to know the names of members of the public who are facing jail sentences, and the names of people or bodies “prosecuting” them – and that right should prevail here.

I’d also urge you to step into the real world and consider how much harm P is really likely to suffer if her mother is named.

The vast majority of people won’t read your published judgment, they’ll find out about the case through the media. In reality, how many passengers on the Seaburn omnibus are going to read a report in the Sunderland Echo then try to piece together an information jigsaw? Dr Kitzinger and I might have the inclination and ability to track down your earlier anonymised judgment on BAILLI, but will the average person really even try? Will they really start searching for the mother’s Facebook and Twitter accounts? Why would they? People have a lot on their minds at the moment. They’re struggling to heat their homes, struggling to pay food bills, war is raging, Prince Harry is on the front pages, Sunderland look like they’re going to miss out on promotion. In reality, this case isn’t big news and I suspect the vast majority will glance at any report, think how sad life is and how lucky they are, then turn to the back page to check the league table.

Likewise, how many people are really keeping track of what the mother is putting into the public domain? She’s not the BBC, she’s not Prince Harry. This case hasn’t been the focus of enormous media attention.

[…]

My proposal [to name the defendant] will obviously create a risk of jigsaw identification; however, I think you can take steps to greatly limit that risk.

Someone always knows the identity of the child, or P. Social workers know, court ushers know, friends of families know, neighbours know. Any report will identify the child, or P, to someone. We’d argue that the test must be “will the passenger on the omnibus, the average person, identify the child, or P?” The test should not be “will anyone identify the child, or P.” If the test is “will anyone identify…?” then the media can never report any family case, or Court of Protection case, because someone will always be able to work it out.

[…]

I suspect that, in reality, only the people who know the family will know the identity of the P, and they must already know. I also suspect that, in reality, relatives, friends, neighbours etc will already know what has happened in this case – and will probably learn of the outcome regardless of whether or not there are media reports.

[…]

I think in any weighing of the Article 8 rights of P, and P’s mother, against the Article 10 rights of the media and the public, the balance here falls on the 10 side. Naming the applicant and respondent would create a limited risk to P: not naming would effectively be secret justice.

(Originally published here: Committal hearings and open justice in the Court of Protection

So, Brian Farmer’s argument is that not naming the applicant and defendant in committal proceedings is “effectively secret justice” and that naming them creates only “a limited risk to P”, such that the Article 8/Article 10 balance comes down on the side of publication. In this case, Mr Justice Poole agreed. Brian Farmer also makes the important point that identification of P is actually rather unlikely to result from naming a defendant in committal proceedings, because that’s not how it works in “the real world”.

I am struck that in Luba Macpherson’s case there’s been no indication either that P has been publicly identified (other than, obviously, by Luba Macpherson herself); or that P has been harmed as a consequence of publication of the name of their mother. (I’m also not aware of publication of P’s identity or harm to P arising out of identification of a contemnor in any other Court of Protection case.)

Each case has a distinctive set of facts relevant to assessing the likely risks to P: for example whether P and the defendant have the same last name, whether they live together, whether there is already media publicity about the case, the use of social media by P and their family members, and what information has been published in previous judgments in the same case. There can be “clear and cogent evidence” of risks to P and these risks may be based on facts not known to observers, who have always a necessarily partial understanding of a case. Equally, the “solutions” proposed to deal with those risks – the enhanced protections provided by new reporting restrictions – may impose impossible burdens on transparency in ways the court does not appreciate since it is bloggers and journalists (and not judges) who have the hands-on experience of publishing information about court hearings.

Given increasing acceptance in the wake of Esper that publicly naming an alleged contemnor is likely to be an inescapable consequence of launching contempt hearings, judges seem now to be less likely to entertain arguments about prohibiting public identification of the defendant, and more likely to be concerned with approaches designed to manage what they see as the resulting risks to the person at the centre of the case. Attempts to identify and manage the risks of jigsaw identification needs to be approached very carefully in these cases, considering the realistic (not merely hypothetic) risks to P, and with a view to necessity and proportionality in creating further reporting restrictions, and their practical ‘real world’ consequences.

We are alarmed by one particular strategy – a strategy we’d characterise as an attempt to sever committal proceedings from previously published judgments (and blog posts) about the same case. We’ve been sent one unpublished contempt judgment which does name the defendant (albeit with no benefit to transparency since we’ve been informed that there is no intention to publish the judgment), along with a draconian new Transparency Order. The new Transparency Order bans publication of the “specific relationship” between P and the contemnor – information already published both in a previous judgment, and in Open Justice Court of Protection Project blog posts which are compliant with the Transparency Order in force up until the date on which the contempt hearing took place. In court, the judge made clear that she was concerned to manage a perceived risk of jigsaw identification if the contempt judgment were to be connected with her own previous judgment in the case. This means, inter alia, that we cannot publish the case number, or the name of the judge or the date of the contempt hearing – all of which are (very) “likely” (in the words of the Transparency Order) to lead readers to the earlier judgment which includes the newly-prohibited information. This is effectively secret justice. We are in the course of making an application for this Transparency Order to be varied and will blog about this separately.

Conclusion

The pilot transparency project in the Court of Protection – which, at least in theory, threw open the courtroom doors to the public and journalists – was launched in 2016. It followed a Daily Mail campaign against committal hearings allegedly held in secret, starting with Wanda Maddocks “the first person known to be imprisoned by the Court of Protection” who was sentenced to five months in prison. The Mail reports that Wanda Maddocks “was initially not allowed to be named after the hearing and was identified only by her initials WM” (a reporting restriction the Mail says was lifted only when P died) “[a]nd the court’s ruling containing details of her sentence was not published”. I checked this out, and there’s a published judgment dated 31 August 2012, which states that the order for committal was made on 10 July (I assume of the same year) (§14 Stoke City Council v Maddocks & Ors [2012] EWCOP B31 (31 August 2012)), so publication of the judgment seems to have been delayed by about two months from the date of sentencing: it’s a short and sketchy judgment, but it does include the length of the sentence.

There have been many really positive changes in the direction of transparency and open justice in the Court of Protection over the course of the last decade. But the evidence I’ve reported here suggests that many committal hearings are still held effectively in secret – if not by design, because they are not listed correctly so we don’t know they’re happening, or because there is no practical means for us to gain access. If we can’t get to hearings and their judgments aren’t published, then even if there’s no court-ordered reporting restriction, the names of the people who received prison sentences, or risked doing so whatever the eventual outcome, are effectively secret. Few people are motivated, as I have been, to pursue the courts to name people (like Tia Bench and David Orange) whose hearings we haven’t been able to attend – and still, despite all my enquiries, I have no idea what either of these defendants was alleged to have done, which orders they disobeyed, whether or not they were found guilty, and what penalties were imposed. And now, post-Esper, the “price” of transparency (in the sense of an increased likelihood that defendants’ names will be published) seems to be that we find ourselves up against draconian reporting restrictions relating to material already in the public domain, severely limiting what we can publish about the case.

So, are contempt of court proceedings now transparent? I’d say, clearly not.

Is the Court of Protection still sending family members to prison in secret? I don’t know for sure. But I suspect the answer is ‘yes’.

Postscript: Good news on transparency (finally) Re: COP 12991351

On 10th March 2025, within 24 hours of publishing this blog post, I received an email from HMCTS responding to my enquiry about the committal judgment handed down in relation to the (incorrectly listed) contempt of court hearing before HHJ Searle. I’m told that a transcript had been requested but not received, and is now being progressed urgently.

Ever since 28th June 2023 (the date the contempt hearing took place), I’ve been raising concerns about the listing of this case, asking about publication of the judgment, and checking BAILLI and The National Archives in hope of finding the judgment. The email trail includes earlier messages from:

- HHJ Searle in person (noting my concerns, and saying she’ll respond in due course, 28 June 2023 – followed on 2 August 2023 by a message from the Bristol office telling me the contemnor’s name and instructing me not to contact the judge directly again);

- the clerk to the Vice President of the Court of Protection (“I have forwarded to Theis J to consider”, 29 June 2023)

- HIVE – an internal Court of Protection group set up during the Covid-19 lockdown to advise on policy matters (“I’ll see what I can find out. Please bear with me“, 11 July 2023) – with a senior HMCTS staff member copied into the email to whom I have been told to direct enquiries

- Bristol HMCTS court staff (“Just to let you know we are awaiting the directions“, 25 August 2023).

Finally, on 26th February 2025, in the course of preparing this blog post, I emailed senior HMCTS staff saying that I’d sent a submission to the Ministry of Justice (which I was now reworking for a blog post), in which I referred to this missing judgment “as evidence of the (sadly, typical) lack of transparency associated with hearings for contempt of court in the Court of Protection”. I wondered if they might be able to pursue what had happened, The 10th March 2025 message saying that no transcript of the judgment had ever been received was the response.

I am baffled and dismayed that neither the judge concerned, nor her “lead judge” (to whom she told me she would refer the matter), nor the Vice President of the Court of Protection, nor HMCTS staff, all of whom I had made aware of this missing committal judgment, were able or willing to pursue this matter until now. It reflects very badly on the Court of Protection’s approach to transparency that my enquiry about a judgment concerning a prison sentence for breaching court orders simply disappeared into a void, with each contact sending me a holding message and then not following up with any action. It’s a devastating derogation from open justice and transparency.

I will blog about the judgment if or when I receive it, and post a link to that future blog post here.

Finally, sadly – but as you might perhaps expect – my experience is shared by other court observers in other courts. Inspired by this blog post, Daniel Cloake (aka Mouse in the Court) posted a blog the day after mine (see “A fight for a contempt of court judgment”). He describes how, when trying to track down a judgment from a contempt hearing in the High Court, he was variously told over a (mere!) six-week period in 2022 that (1) the judgment didn’t exist (30th May); (2) “there is no judgment as such on the file, although it looks like Judgment is in the form of an order” (1st June); (3) that the interlocutor “didn’t really know as this is not something I normally deal with” (1st June); (4) that he’d have to pay for a transcript – likely several hundred pounds (6th July); before finally – (5) “After speaking to the Judge’s then clerk, I have been able to obtain a transcript of Arnold J’s judgment” (6th July).

The courts urgently need to consider how better to manage the publication of committal judgments.

UPDATE

The judgment has finally been published: Torbay Council v Tia Bench & Anor [2023] EWCOP 75 (T2).

Tia Bench was given a suspended custodial sentence on 28th June 2023. The judgment publicly reporting this custodial sentence was published about 22 months after sentencing.

There’s a note at the beginning of the published judgment saying: “This judgment was handed down orally at the end of the Committal hearing. The approved order of 28 06 2023 directed a transcript and publication of this judgement. Publication until now has not taken place.” I can’t see any date on the judgment indicating what date it was published (i.e. when “now” was), but on 23rd June 2025 I received an email from a Court of Protection Operations Manager sending me the link to the judgment and telling me, in response to my latest email (dated 18th June 2024) chasing this judgment, that: “The judge was informed on 24.04.2025 that the judgment “Torbay Council v Tia Bench & Anor”, reference TDR-2025-CRMS, has been published on Find Case Law“, so it sounds as though it was published by the end of April 2025. Nobody thought to inform me although I have been chasing this judgment for nearly two years.

The delay of 22 months in publishing a committal judgment is obviously unacceptable. It is all the more shocking because (as documented above) I was repeatedly asking judges and HMCTS staff for the judgment over that time span. My multiple requests were largely ignored I published my submission to the Ministry of Justice Law Commission Consultation on contempt of court, which referred to this case. It should not be necessary to involve the Ministry of Justice, or to publicly blog about the court’s failings, before a committal judgment is finally published.

Part of the delay in publication was also occasioned by a judicial decision (reported in an email with attached order on 3rd April 2025) to consult counsel (and me) about naming the contemnor, Tia Bench, in the published judgment. I had already publicly named her in this blog post and on social media posts, in accordance with the reporting restrictions in force at the time I did so. Since I was not provided with any information about Tia Bench, the actions she had committed that constituted contempt of court, or her sentence, I informed the judge that I was unable to see any reason why the usual rules (i.e. that a contemnor should be named) would apply. I also informed the judge that, in the event that any party made submissions that the contemnor should be anonymised in the published judgment, I wanted the opportunity to make an application for naming the contemnor. Despite subsequently asking (on 16 May 2025, 3rd June 2025 and 18th June 2025) whether whether further submissions were needed from me, and what decision the judge had made, I heard nothing more, until the email of 23rd June 2025 telling me that the judgment was now published. This lack of communication is also unhelpful for those of us seeking to support transparency in the court.

From reading the judgment, this sounds a very sad case – for the protected party, obviously, but also for Tia Bench. We have blogged recently about a couple of different cases of contempt of court where there have been concerns that the contemnor lacks capacity either to understand and comply with a court order, or to litigate the contempt proceedings. There is no suggestion of lack of capacity in this judgment, but it does record that: “Ms Bench has done her best to inform the court of her own vulnerability. The court has been told that she will do anything to avoid going into prison and having a sentence activated. The court understands that her own evidence is that she has a borderline personality disorder which has not helped her react appropriately to the injunction and to the suspended sentence“. (§16 Torbay Council v Tia Bench & Anor [2023] EWCOP 75 (T2)). Ms Bench – who was on benefits – asked to be fined rather than sent to prison (§10): she recognised that she should not have breached the injunctions (§10) and sought to reassure the court that she would not breach the injunctions (preventing her from spending time with the protected party) in future (§17). The court considered the possibility that these were “crocodile tears” and that she was merely “trying to convince the court of the fact that she will now turn over a new leaf” (§18), but the judge was willing to give her the benefit of the doubt. Instead of activating the suspended sentence of 14-days imprisonment (which must have been imposed in an earlier committal hearing of which I was previously unaware), the court re-sentenced her to a further 4 days, making a total of 21 days suspended for 12 months (§19). The judge warned: “I want Ms Bench to be absolutely clear that if she, in any way, associates with [the protected party] and continues to breach the injunction which will continue, that it is almost inevitable that she will now go to prison and the sentence will be activated. I am prepared to give her a second chance, but I want her to be absolutely clear that it is most unlikely that there will be a third chance”. (§20).

Those sentencing remarks, only recently published, were made on 28th June 2023. I wish I could be sure that any subsequent committal hearings concerning Tia Bench had been properly listed and any committal decisions published. Obviously, given the history of this case, I cannot be confident that this is so. I have now asked for confirmation that there have been no further committal hearings in this case since June 2023. (I received a same-day response to my enquiry on 24th June 2025: “There have been no further committal applications in this matter.”)

Celia Kitzinger is co-director of the Open Justice Court of Protection Project. She has observed more than 600 hearings since May 2020 and written more than 100 blog posts. She is on LinkedIn (here), and also on X (@KitzingerCelia) and Bluesky @kitzingercelia.bsky.social)

[1] According to the MOJ consultation paper: “Transparency data” is the term generally used to describe data that is published on the government websites pertaining to the work of different government departments. A wide range of information is published for the purposes of enhancing transparency, for example, prison population figures, spending for services for government departments, data about senior civil servants in the Cabinet Office, as well as more specific data such as outcomes of unduly lenient sentence referrals by the AG.’ (footnote 7, Chapter 7, p. 170).

[2] Ministry of Justice data on prison receptions records that over 100 people were imprisoned for contempt from 2020-2022 (quoted in footnote 3 on p. 1, Ministry of Justice Contempt of Court Consultation paper (July 2024). Based on my observations of custodial sentences handed down in the Court of Protection this is a surprisingly low number, even allowing for successful appeals – unless perhaps custodial sentences for contempt of court are disproportionally frequent in the Court of Protection compared with other courts.