By Amanda Hill and Claire Martin (with acknowledgment of significant input and support from Celia Kitzinger)

Update 26 May 2025: The application to vary the reporting restrictions was successful and a judgment, [2025] EWCOP 16 (T3), was published on the National Archives Friday 23 May 2025. We will blog about the hearing to vary the Transparency Order later. But we are now allowed to report that this committal hearing related to COP14187074. This is a case we have blogged about previously:

A few months ago, we observed a committal hearing at the Royal Courts of Justice at which someone was found to be in contempt of court for having breached undertakings and injunctions and given a (non-custodial) sentence.

We believe that the way these proceedings were managed does not meet the judicial aspiration for transparency in the following key ways:

- The public don’t know that the committal hearing even took place, because it wasn’t listed correctly as a committal: there was no public information in advance of the hearing about which public body made the committal application, and no record of the name of the person who faced being sent to prison, or fined, or having her assets seized[1].

- The judgment – which does name the local authority and the defendant – has not been published. This means there is no public record of what undertakings and injunctions the defendant was found to have breached, or what sentence was handed down. There is also no public record of the applicant’s and defendant’s names: we’ve been unable to find the defendant’s name on the judicial website.

- We are banned from reporting on the substantive content of the committal proceedings including, in particular, reporting on the proceedings in any way that connects the committal with the previously published fact-finding judgment in the same case, and with our blog posts and other published legal commentary about the case.

Here’s what happened in relation to each of these concerns in turn. We’ll chart the problems here and then turn, in the second part of the blog post, to what actually happened in the hearing we attended[2].

1. The hearing wasn’t listed as a committal hearing

The hearing was listed incorrectly – as is often the case (see: Contempt of court proceedings: Are they transparent?). The Practice Direction: Committal for contempt of court – open court sets out the standard format that should normally be used.

This was not complied with. Neither the name of the applicant nor the name of the defendant were provided in the public listing on the Royal Courts of Justice public website, and nor were the words “committal to prison” used.[3] This was apparently a mistake and not as a consequence of judicial direction: “With regard to the incorrect listing of the committal (which is also acknowledged in the judgment itself), this was due to an administrative error in the listings office. The court apologises for this”[4].

We knew it was a committal hearing because people involved with the Open Justice Court of Protection Project have been following this case for a while, and we knew that a committal hearing had been planned for this case on that date with this judge and we had arranged, in advance, to attend in person. We also advertised the fact of the upcoming committal hearing on our WhatsApp group for people interested in observing hearings, and we’d supplied links to the previous blog posts and judgment: one other observer attended remotely as a result. We do not know whether the judge had alerted the Press Association to this hearing – as also required by the Practice Direction – but in any event no journalists were in court.

2. There is no published judgment

A judgment was handed down which finds the defendant in contempt of court on five grounds and imposes a (non-custodial) sentence upon her.

We have been sent a document with 50 numbered paragraphs setting out the background to the case, the grounds on which the applicant local authority claims that the defendant is in contempt of court, the judge’s views on the evidence, and her decision and sentencing. The document resembles a published judgment in its format and layout, save that it specifies on its face that the judgment is “ex tempore”, and the space where the “Neutral Citation Number” should go has been left blank. A recital at the beginning of the judgment says that it is ”PURSUANT TO the guidance in Esper v NHS NW London ICB (Appeal: Anonymity in Committal Proceedings) [2023] EWCOP 29)” – which is the leading case law on the matter.

There is no legal requirement on the judge to publish the judgment because, although the defendant was found to be in contempt of court, she was not sentenced to prison. According to Poole J in Esper:

“If the court finds the defendant in contempt of court but does not make a committal order, then a reasoned judgment must be given in public and the defendant must be named in court and their name published on the judiciary website, but there is no requirement for a transcript of the judgment to be published on the judiciary website, although the court may choose to do so.” (§54(x)(b) in Esper v NHS NW London ICB (Appeal: Anonymity in Committal Proceedings) [2023] EWCOP 29)

We’ve been told that the judge “does not intend to publish her committal judgment” (email from judge’s clerk), so it will not appear on any of the usual sites (BAILLI, The National Archives, or the judicial website) where members of the public can access it.

We note that – contrary to the guidance in Esper (§54(x)(b))quoted above– there does not seem to have been any publication of the defendant’s name on the judiciary website (at least not where we’ve been able to locate it).

So, for now, only the people directly involved in the case and those of us associated with the Open Justice Court of Protection Project, are aware that a named individual has been found in contempt of court for breaching specific undertakings and injunctions, and she has been sentenced for those breaches, and what the sentence is.

3. A new reporting restriction effectively bans us from reporting the substantive content of the committal proceedings

During 2024, observers watched hearings in this case and blogged about them in compliance with the reporting restrictions imposed by the court, which were in all relevant respects those set out in the “standard” Transparency Order.

In 2025, the judge made a new Transparency Order (TO) specifically for the committal hearing. This is common practice because the “standard” Transparency Order states that the injunction “does not apply to a public hearing of, or to the listing for hearing of, any application for committal” (§9(iii) in the template, though its paragraph number may be different in any actual TO). The “standard” TO doesn’t apply to committal hearings because they are a different kind of proceeding, with rules all of their own[5].

In committal hearings, the name of the person facing a prison sentence should usually be published – even if publication of their name had previously been prohibited because they are a family member of the protected party.

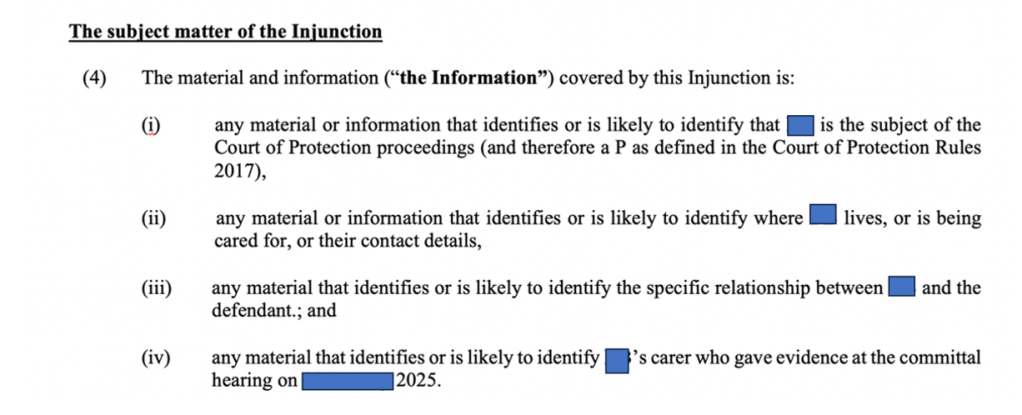

Here’s the salient part of the 2025 TO.

Like the 2024 TO, the new TO in this case prohibits publication of the name of the person who is the subject of the Court of Protection proceedings and anything that is “likely” to identify her, or where she lives, or the name of her carers. But it does not specifically prohibit us from naming the family member who is the defendant in this committal hearing. The defendant’s name appears on the face of the unpublished judgment – as does the name of the applicant local authority – as well as, several times, in the body of the judgment itself.

The problem we face in writing about the case is not that we cannot name the defendant – we can! – but that the new TO (unlike the previous one) prohibits publication of information “that identifies or is likely to identify the specific relationship” between [the protected party] and the defendant – and this information is already in the public domain.

The “specific relationship” (i.e. the nature of the family connection between P and the defendant, e.g. aunt/niece; grandmother/granddaughter) is revealed in the publicly-available fact-finding judgment in this case, published in 2024 a few months before the committal hearing took place. In the opening paragraphs of that judgment, the judge says of the person who is now the defendant that she “is P’s [X]” – where X names the “specific relationship” between them – and in the course of that judgment, there are more than 100 references to this “specific relationship”[6].

Of course, at the point that judgment was published, the family member referred to in the fact-finding hearing was not yet a “defendant” in a committal hearing – but the judge helpfully says, in her 2024 judgment that there will be a committal hearing concerning this family member[7], and she names the date. So, anyone reading the 2024 fact-finding judgment –available on public websites – has unfettered access to information about the “specific relationship” between the defendant-to-be and the protected party.

We have experimented with google searches and with the search facilities in BAILLI and the National Archives to ascertain what information is “likely” (the word used in the TO) to lead people to uncover the “specific relationship” between the defendant and the protected party, as referenced repeatedly in the published judgment. Obviously, this includes any explicit link to the previous judgment (we would normally consider it good practice to provide the judgment name and an electronic link). Since (it turns out) this judge is not a prolific publisher of judgments, information “likely” to lead people to her previous judgment in this case, also includes: the judge’s name, the date of the hearing, names of counsel, and distinctive facts about the undertakings and injunctions breached by the defendant (also covered in the ‘fact finding’ judgment).[8]

The Open Justice Court of Protection Project also published blog posts over the course of 2024 making explicit the “specific relationship” between these family members – as have other legal commentators. At the time these blog posts (and legal commentaries) were published, this was not prohibited by any court orders – and it is well established that reporting restrictions cannot be imposed retrospectively (Roberts J, §109 in Re BU [2021] EWCOP 54). We would normally provide links to previous blog posts (and perhaps to legal commentaries) as part of our effort to present a case ‘in the round’. We cannot do that now without breaching the 2025 TO.

What all of this means is that we can’t report on the committal hearing in any way that relates it either to the public judgment that the (same) judge has already published about this case, or to our previous blog posts or to others’ legal commentary about the case. To do so makes it “likely” that readers would be able “to identify the specific relationship between [the protected party] and the defendant” (TO, (4)(iii)).

In effect, the reporting restrictions in the 2025 TO sever the link between the committal hearing and everything that has happened in this case previously – as reported in the judgment, blogs and legal commentary from 2024[9].

This is a very serious interference with the public’s Article 10 rights to freedom of information. Thousands of people have read our previously published blog posts about this case. There is a legitimate public interest in learning what happens when family members are found to have breached undertakings and/or injunctions in the Court of Protection. The effect of the injunction against us is that people can read about the events leading up to the committal hearing (in our blogs, in the legal commentary and in the 2024 judgment that announces the forthcoming committal proceedings) – but the trail stops there, with no public report of the committal itself.

We have submitted a formal application for variation of the Transparency Order to remove §4(3) (i.e. the prohibition on naming the “specific relationship” between the defendant and the protected party).

Why and how did the judge make the 2025 Transparency Order?

We attended this full-day committal hearing in person at the Royal Courts of Justice in London.

The hearing began without us having had sight of a Transparency Order. We’d asked counsel for the TO (and for the Position Statements) immediately before the hearing started, but it seemed there wasn’t one – not even in draft form for the judge to approve.

Consequently, the question of reporting restrictions was the first issue for the court to address.

Because – as a consequence of the “administrative error in the listings office” – the defendant’s name had not yet been made public via the committal listing as it should have been, this raised the possibility of a Transparency Order banning publication of her name altogether. The parties took different positions on this point.

Counsel for the Local Authority opened the proceedings by citing Esper and saying that the default position in committal proceedings is that the name of the defendant should be published. The court should also consider whether additional reporting restrictions were needed in view of the possibility of ‘jigsaw identification’ of the protected party once the defendant’s name was in the public domain, but “the predicament that [P] faces is already well-known to those who know her … and this is not a case where she would be placed at risk, for example from vigilante groups if the defendant’s name is published…. So the defendant’s name should be permitted to be published and the TO should be amended to permit that”.

Counsel for the Defendant submitted that the judge did have the power to make an order to prohibit reporting of the defendant’s name, and that she should do so because “the reporting of [defendant’s] name is almost bound to lead to [P’s] name being revealed” because of the specific family relationship between them.

Counsel for P (via the Official Solicitor) had not yet received instructions but took the interim position that the new Transparency Order should continue the protection afforded by the previous Order to the identities of P and her carers, and that “the only issue is whether [the defendant’s] name should be permitted to be reported”. He accepted that there is a risk of P being publicly identified as a result of identification of the defendant, who is a member of her family. The judge asked whether there was a way to prevent reporting of the specific relationship between the defendant and the protected party, and counsel said yes, “that happened in Esper – the defendant was identified only as a ‘relative’, so that may be an avenue”.

The judge decided to “see where we get to by the end of the day” before making a decision about the reporting restrictions – not least, since there would be different requirements concerning publication of a judgment depending on whether or not she handed down a custodial sentence (which would require a published judgment). She reflected out loud however that “I wouldn’t want [the defendant] to be identified as P’s [specific kinship relation]… ‘Relative’ is a better approach”.

Counsel for the Local Authority pointed out, in response, that “the only thing is, if there is a published judgment from today, is it going to have the case number on it? That is a difficulty because the case number is linked to the previous hearings and will identify [the defendant] as the [specific kinship relation] of the protected party…. It would be obvious that [the defendant] is the [specific kin]”.

The judge accepted this, remarking “the cat would be out of the bag”. Pending determination of the reporting restrictions, she ruled that we could not report at all during the hearing – including a reporting restriction on the discussion about the reporting restrictions.

The parties then focussed on the matter of the committal, of which we can provide only a minimalist account. Essentially:

- The defendant admitted breaches to undertakings she’d made regarding contact with the protected party – including having unsupervised contact and behaving towards P in ways that caused P to become upset and distressed. But she did not accept that she was in breach of the two terms of an injunction (the details of which we can’t give).

- In relation to breach of the injunction (not admitted), a carer was sworn in to give evidence and be cross-examined about an “incident” she witnessed at which the defendant allegedly raised matters known to be upsetting to the protected party.

- The defendant exercised her right to silence and did not give oral evidence (which is apparently a choice from which – it was determined – the judge can draw adverse inferences).

- Counsel for the Local Authority argued that the evidence of the witness met the criminal standard of proof for a breach; the defendant’s counsel argued that it did not; and on behalf of P, the Official Solicitor took a neutral stance.

- The judge found the defendant to have disobeyed the law and to be in contempt of court on all the grounds raised (bar one that was withdrawn by the Local Authority), including breach of the injunction.

- The parties made submissions about the appropriate punishment – nobody argued for a custodial sentence: the breaches were said not to meet the requisite threshold (the Local Authority), not to be in P’s best interests (the Official Solicitor) and not to be merited given the “loving” relationship between the defendant and P, and the defendant’s commitment to P’s best interests as she sees them, at a time of some personal difficulties for the defendant. The judge imposed a penalty short of a custodial sentence. There was no application for costs.

The court then returned to the matter of reporting restrictions. The focus was firmly on the matter of whether or not the defendant should be named.

Counsel for the LA: Talking about whether a defendant’s name should or should not appear in the court list, it [i.e. Esper, specifically, “Conclusions on PD 2015 and COPR r21.8(5) §54 III”)] says the defendant should be named, that anonymisation is derogation of open justice.

Judge: I assume [the defendant’s] name was listed in the court list?

Counsel for the LA: No. ((Judge shakes head)). Mr Justice Poole noted in that case [i.e. Esper) that it was not the first time it (i.e. failure to name the defendant in court lists) had happened. So, your order was not followed. I don’t know if there’s anything you can do behind the scenes in future to prevent that happening. [The defendant’s] name should have been made public prior to today’s hearing. ((He then took the judge through the relevant law and guidance, concluding that the defendant should be named in the judgment.)) We can’t say [the defendant’s] name should not be published in order to protect [P’s] identity. There’s always a risk of jigsaw identification. You’ve already anonymised the initials in the previous judgment. This is not a case where harm would come to [P] if her name was inadvertently found out, even though there would be prohibition – our understanding is that the wider family and those caring for [P] are aware of the dynamic in the family and aware of the COP proceedings […]. The interests of open justice should prevail. There is public interest in learning the identity of people who are subject to committal proceedings. In this case, this is not a high-profile case with a lot of media attention. If people do find out, they are prevented from publishing the name of [P] in any event…. Your judgment from [2024] did say that there would be contempt proceedings in the New Year…. We say there is public interest in knowing what’s happened in that application.

Counsel for the defendant returned to the problem that, in their view, identification of the defendant would “inevitably” lead to public identification of P. He suggested that “it may be that taking different initials is the approach the court takes” (i.e. using different initials for the parties in the contempt proceedings from those used in the fact-finding proceedings) in order to avoid “the two judgments [being] linked”. He said: “My instructions are to raise concerns about P being identified, and to ask the court to give consideration to ways those risks can be minimised. Of course, the obvious way is for [the defendant] not to be named at all, but the court needs to consider open justice…. I suppose my closing submission is this: if the court considers that naming [the defendant] has the inevitable impact of identifying [the protected party] as P within the Court of Protection proceedings, then if there’s no way of ameliorating that risk, we would be concerned about that course of action, from the perspective of wishing to protect P’s identity”.

Counsel for P (via the Official Solicitor) expressed concern about naming the defendant in a context where the committal proceedings had been brought for the protection of P, and naming the defendant risks undermining the protection (of her privacy) that has been put in place for the welfare and fact-finding proceedings. He hoped that there might be “a sensible and appropriate way to name [the defendant] without risking jigsaw identification of P”.

We were asked for our views as public observers at this point[10] and took the general position that it was important for open justice to be able to name the defendant. We were not asked to consider, and did not think to address, the question of whether the defendant’s “specific relationship” with the protected party should be concealed – and, in retrospect, that was a mistake. If the judge had raised this as a possible outcome, we would have explained that not only had the previous judgment made this relationship explicit, but also that the Open Justice Court of Protection Project blog posts had too. But we are not lawyers and not accustomed to being asked to make submissions in court, and were doing so ‘on the hoof’, without having had an opportunity to prepare. On previous occasions when we’ve made submissions in court, we’ve had the TO in front on us and have been able to point to particular wording as problematic – but there didn’t seem to be any concrete proposals (other than a total ban on naming the defendant) before the court. We had simply not appreciated at the time that naming the defendant but obfuscating her relationship with the protected party was a likely outcome. Our focus was instead on ensuring, as far as possible, that publishing the name of the defendant would not be prohibited.

Counsel for the Local Authority repeated again words to the effect that the principle of open justice weighs heavily here, despite a risk of jigsaw identification, and that it’s “important that there is continuity between the judgments”so that the case can be understood in the round.

The judge concluded by saying that she would not give a ruling on the transparency issues that evening and that the existing Transparency Order would remain in effect until she had made a decision about whether or not the name of the defendant could be published. She indicated that her decision would be communicated within five days or so.

In fact, the new TO was not issued until three weeks after the hearing – and we received it only after Amanda wrote to the judge enquiring about it.

We were shocked when we read the new TO – immediately realising that it severs the link between the 2024 fact-finding judgment and the 2025 committal judgment. The prohibition relating to the “specific relationship” between defendant and protected party (combined with the changed initials for the parties) ensures that nobody except the observers and those involved in the case can know that the two judgments refer to the same case. This is not open justice.

There may be circumstances under which it is necessary and proportionate to sever the continuity of two judgments in a case and to block transparent reporting. But we have not heard any arguments in this case to indicate that P’s Article 8 privacy rights (or her right to protection from harm) would be so desperately imperilled by reporting the “specific relationship” between her and her family member as to justify this draconian restriction on the public’s Article 10 right to freedom of information.

We will report back on the application to vary the 2025 Transparency Order in due course.

Amanda Hill is a PhD student at the School of Journalism, Media and Culture at Cardiff University. Her research focuses on the Court of Protection, exploring family experiences, media representations and social media activism. She is also a daughter of a P in a Court of Protection case and has been a Litigant in Person. She is on LinkedIn (here), and also on X as (@AmandaAPHill) and on Bluesky (@AmandaAPHill.bsky.social)

Claire Martin is a Consultant Clinical Psychologist, Cumbria, Northumberland, Tyne and Wear NHS Foundation Trust, Older People’s Clinical Psychology Department, Gateshead. She is a member of the core team of the Open Justice Court of Protection Project and has published dozens of blog posts for the Project about hearings she’s observed (e.g. here and here). She is on X as @DocCMartin and on BlueSky as @doccmartin.bsky.social

[1] For convenience, we refer to the defendant, the protected party and the judge using feminine pronouns (she/her etc) and to all the barristers in court (representing the applicant LA, P via the Official Solicitor and the defendant) using masculine pronouns (he/his etc). Readers should not, however, draw any inferences as to the sex or gender identity of these persons.

[2] The two observers who wrote this blog post were Amanda and Claire. Celia Kitzinger was out of the country and without internet access at the time of this hearing, but as co-director of the Open Justice Court of Protection Project became involved on her return in trying to untangle the complex transparency issues involved in this case. She also took responsibility for submitting the COP 9 application to vary the 2025 Transparency Order. Thank you also to Daniel Clark for exhaustive experiments with different search terms in different search engines to determine how “likely” it was that naming the judge or giving the date of the committal hearing (for example) would lead to information about the “specific relationship” between the defendant and the protected party.

[3] In the unpublished judgment from this committal hearing, the judge says: “it was unfortunate that the court list did not show the defendant’s name but identified her by initials” (§15). This is incorrect: the initials that were published were not the initials of the defendant, but the initials of the protected party. The judge does not comment on the fact that the word “committal” was not used in the listing or on the failure to publish the name of the applicant public body in the list.

[4] Extract from an email sent by the judge’s clerk. (We’ve avoided giving the date and other details since to do so would increase the likelihood of readers becoming able to source information prohibited by the 2025 Transparency Order in this case.)

[5] See the Lord Chief Justice’s Practice Direction on committal for contempt of court and (especially) Esper v NHS NW London ICB [2023] EWCOP 29, in which Poole J offers a thorough review of the rules around contempt and transparency – including the interplay of different regulations.

[6] In the 2024 judgment, the defendant is referred to more than 30 times by reference to her “specific relationship” with P (e.g. “niece”) and the protected party is referred to more than 70 times by reference to her “specific relationship” with the defendant (e.g. “aunt”) – although, for the avoidance of doubt, we point out that this is illustrative only and that the reader should not draw from this example any inference as to the actual relationship of defendant and P. Our point is simply that the published judgment repeatedly invokes the “specific relationship” between the defendant and P in sentences such as: “She told her aunt…”….“She accepted that her aunt….” and “There was concern that her niece….”… “Her niece was observed by the social worker to….”).

[7] The judge said, in the course of the committal proceedings, that she “rather regrets” having included reference to the upcoming committal hearing in the fact-finding judgment.

[8] It would be possible to argue, in our defence, that, although naming the judge (for example) would make it easy in principle for people to identify the previous judgment in this case, and hence to identify the “specific relationship” between defendant and protected party, would anyone really bother? It would take less than 5 minutes to anyone familiar with the relevant legal archives, but the reality is (it could be argued) that very few readers of our blog posts will be sufficiently motivated to discover the “specific relationship” between the defendant and the protected party that they would enter the judge’s name into a National Archives search and open all her 2024 judgments to detect the one adumbrating an upcoming committal. People have other, more pressing, demands on their time! We don’t advance this argument for the following reasons: (1) it is a matter of principle that we should be able to link to published judgments, and this principle should not be predicated on an assumption that it’s unlikely that members of the public will click on these links; (2) in fact, in the last 12 months there have been more than 1,800 clicks on links from our blog posts to BAILLI, the National Archives, and the judicial website where judgments are published, so clearly some readers are accessing judgments from our blogs; (3) the 2025 Transparency Order is an injunction against us with a penal notice, and we don’t want to risk committal for contempt of court on the basis of an untested argument about how “likely” is it (or isn’t) that linking to a judgment will mean people (a) click on it, (b) read it, and (c) discover the “specific relationship” between the defendant and the protected party.

[9] The 2025 TO also refers to the protected party (and another family member) with different initials from the initials deployed in the 2024 judgment (which already represented a different set of initials from those used in listings for earlier hearings in the same case). This third set of initials makes it less likely that anyone casually stumbling over the fact-finding judgment will recognize it as relating to the committal judgment (which is public albeit not published) simply on the basis of the initials on the face of the judgment. The decision to create a third set of initials for the parties must be part of a deliberate strategy by the court to sever the connection between the committal and the previously published judgment. (The judge’s stated “regret” at having announced the upcoming committal hearing in her 2024 published judgment supports that interpretation.)

[10] Perhaps our position in the physical courtroom, sitting front and centre on the press bench focused attention on us. We’d asked to sit there in order to be able to hear better (and there weren’t any journalists in court competing for those seats). At one point earlier in the hearing, counsel for the Local Authority had looked over at us and said “The observers in court are responsible legal bloggers and part of the Open Justice Court of Protection Project and they won’t make it easier to identify (P)”. Another observer was watching the hearing via the video-platform, but was not asked for her views about the Transparency Order. It may also be relevant to point out that we’re not technically “legal bloggers”, as that term is used in the Family Court Transparency Pilot (Family Practice Rule 27.11). In the Family Court, “legal bloggers” is defined with reference to ‘duly authorised’ lawyers (see: Legal Blogging and the Open Reporting Provisions). We blog about legal matters and hearings we have observed but we aren’t lawyers. (The judge also refers to us as ‘legal bloggers’ in §15 of her unpublished 2025 committal judgment.) Finally, the 2025 Transparency Order has an opening recital “UPON hearing from…” which lists counsel for the applicant, counsel for the defendant and counsel for the first respondent, but (curiously) not us, despite the fact that the judge asked for our views and we provided them in court.