By Claire Martin, 30th July 2025

Luba Macpherson[1] is a woman with strongly held views regarding the care and treatment of her daughter. The Open Justice Court of Protection Project has published several blogs about the case, most recently this blog by Amanda Hill: ‘Strongly held beliefs do not equate to lack of litigation capacity: Judgment concerning Luba Macpherson’s appeal against committal to prison’. I quote the blog at length below to summarise the case history and current situation:

“Luba Macpherson has been involved as a party (sometimes as a litigant in person, sometimes with legal representation) in a long-running Court of Protection case concerning her daughter, referred to as “FP” in the judgments, who has been diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia. Luba’s daughter lives in a care home and Luba believes she is being abused and is being given medication that is making her symptoms worse. She has regularly communicated her views on these matters to her daughter, with the result that the court has authorised various forms of contact restrictions (and at times a total ban on contact). More detail is available in a published judgment (SCC v FP and others [2022] EWCOP 30) and in a previous blog about this case: An ‘impasse’ on face-to-face contact between mother and daughter.

During the proceedings concerning Luba’s daughter, the Court of Protection judge, Poole J, made an injunction prohibiting Luba from posting material about FP on the internet. […] After Poole J made this injunction, Luba continued to post material about FP on the internet (she still does). Her rationale for breaching the injunction is that the court is engaged in a cover-up. […]

In January 2023, Poole J found Luba in contempt of court for having breached his injunctions by posting material about her daughter online. The judge imposed a suspended 28-day sentence (judgment here [2023] EWCOP 3). We’ve also blogged about it: “A committal hearing to send P’s mother to prison”).

Luba appealed against this 28-day suspended sentence. […] Her 4th May [2023] appeal was dismissed.

After having received a suspended 28-day sentence, and after her appeal against it was dismissed, Luba continued to post videos and other material about her daughter. The local authority issued fresh committal proceedings – although by now Luba had relocated to France, where she was outside the jurisdiction of the court. Since Luba declined to return to the UK for the contempt hearing, the judge made a warrant for her arrest. At a hearing on 22nd January 2024 (which Luba attended remotely from France), Poole J imposed an immediate 3-month sentence for the new breaches, plus the 28-day sentence from January 2023, making a total of 4 months of imprisonment. We blogged about that hearing too: “Warrant for arrest of P’s mother”).

Luba wants to appeal that judgment (sending her to prison for 4 months) in the Court of Appeal. She filed her application to appeal a long time ago, on 21st March 2024, but it’s still not been heard. First there was a delay in securing legal aid, and then a delay due to a failed attempt to secure a transcript of the committal hearing. Most recently, the appeal has stalled altogether due to Luba’s own legal team having raised concerns that their client lacks capacity to litigate. ”

The question of whether or not Luba has litigation capacity was referred back to the Court of Protection to determine.

So, in the past year, Luba has herself become a protected party ( ‘P’) in the Court of Protection, with her capacity to litigate questioned by her own lawyers. Amanda has reported, in detail, on the Court of Appeal hearing regarding committal (3rd December 2024) and the Court of Protection hearing regarding litigation capacity (which was heard on 30th April 2025 by Mrs Justice Theis).

In this blog, I want to think about what is meant in general by litigation capacity and explore the trajectory of Luba’s case with reference to wider issues, such as the ‘protection imperative’. I have structured the blog as follows:

- How did it come about that Luba’s capacity to litigate was questioned?

- What is meant by capacity to conduct proceedings?

- Concerns about Luba’s behaviour and conduct earlier in the proceedings

- The protection imperative

- Reflections

1. How did it come about that Luba’s capacity to litigate was questioned?

I’ve followed this case with interest[2] and have witnessed Luba Macpherson’s grit and resilience throughout. It’s evident that Luba is passionate in the defence of her beliefs about what is the best and most appropriate care and treatment for her daughter, her beliefs about the legal and healthcare systems swirling around both of them, and, recently, her assertion of her own capacity as a litigant in person.

One feature of the case has been how Luba herself (and her mental health) has been characterised by others over the course of the hearings – culminating in the claim that there was reason to believe that she lacks capacity to conduct legal proceedings.

On the face of it, it seems odd that Luba’s capacity to conduct proceedings has recently become an issue. After all, she has engaged with the court across multiple hearings, over many years, beginning in 2018: first in hearings about the best interests and care of her daughter, and then about contact with her daughter (see the judgment of HHJ Moir in October 2020 ([2020] EWCOP 75); and latterly in relation to contempt of court (see Poole J’s judgments: at [2022] EWCOP 30 and at [2023] EWCOP 3 ; the Court of Appeal judgment 2023 [2023] EWCA Civ 574) and a committal hearing (see Poole J’s committal order [2024] EWCOP 8). At some of these hearings, over many years, Luba was a litigant in person, at others she instructed lawyers to act for her.

And then, after around six years of litigation, on 6 November 2024, her lawyers became concerned about her capacity to conduct the proceedings (which now constituted an appeal against her sentence for contempt of court). I don’t know the basis for that concern but according to Law Society guidance on ‘What should I do if my client loses capacity?’ the lawyers had a duty to act: “Under paragraph 3.4 of the SRA Code of Conduct for Solicitors, RELs and RFLs, you must consider and take account of your client’s attributes, needs and circumstances. If you’re not able to form a view about the client’s capacity or an assessment is required for court purposes, such as an application to the Court of Protection, you should seek the opinion of an appropriately skilled and qualified professional.”

So, they took their concern to the Court of Appeal who authorised an expert (Dr Pramod Prabhakaran, a psychiatrist) to undertake a paper-based assessment of Luba’s capacity to conduct proceedings (since she declined to participate in a face-to-face assessment).

That led in turn to a Court of Appeal judgment in 2024 which found “reason to believe” that she lacked mental capacity to conduct the proceedings. The Court of Appeal referred the matter of Luba’s litigation capacity back for the Vice-President of the Court of Protection (Theis J) to determine, with Luba now as a ‘protected party’ pending that decision (see the Court of Appeal judgment of King LJ [2024] EWCA Civ 1579).

After considering the evidence, Mrs Justice Theis found Luba to have capacity to conduct the proceedings in the Court of Appeal (and, retrospectively, that she’d had capacity to conduct proceedings at the contempt hearings the judgments from which she was now appealing [2023] EWCOP 3).

I’m not surprised at the finding that Luba Macpherson has capacity to conduct legal proceedings. I was surprised that her capacity was questioned. At all the hearings in this case that I’ve observed, I have witnessed Luba expressing herself articulately and forcefully. At times she’s been unwilling to accept and comply with the usual etiquette of the court – which is in any case opaque to many litigants in person. She’s frequently been told by judges that she’s interrupting them or presenting arguments not germane to the issues before the court. She has her own views on the court process, and on what the relevant issues are for her daughter’s care, and has openly (on social media) described the courts and judiciary, Local Authority and care system as ‘corrupt’.

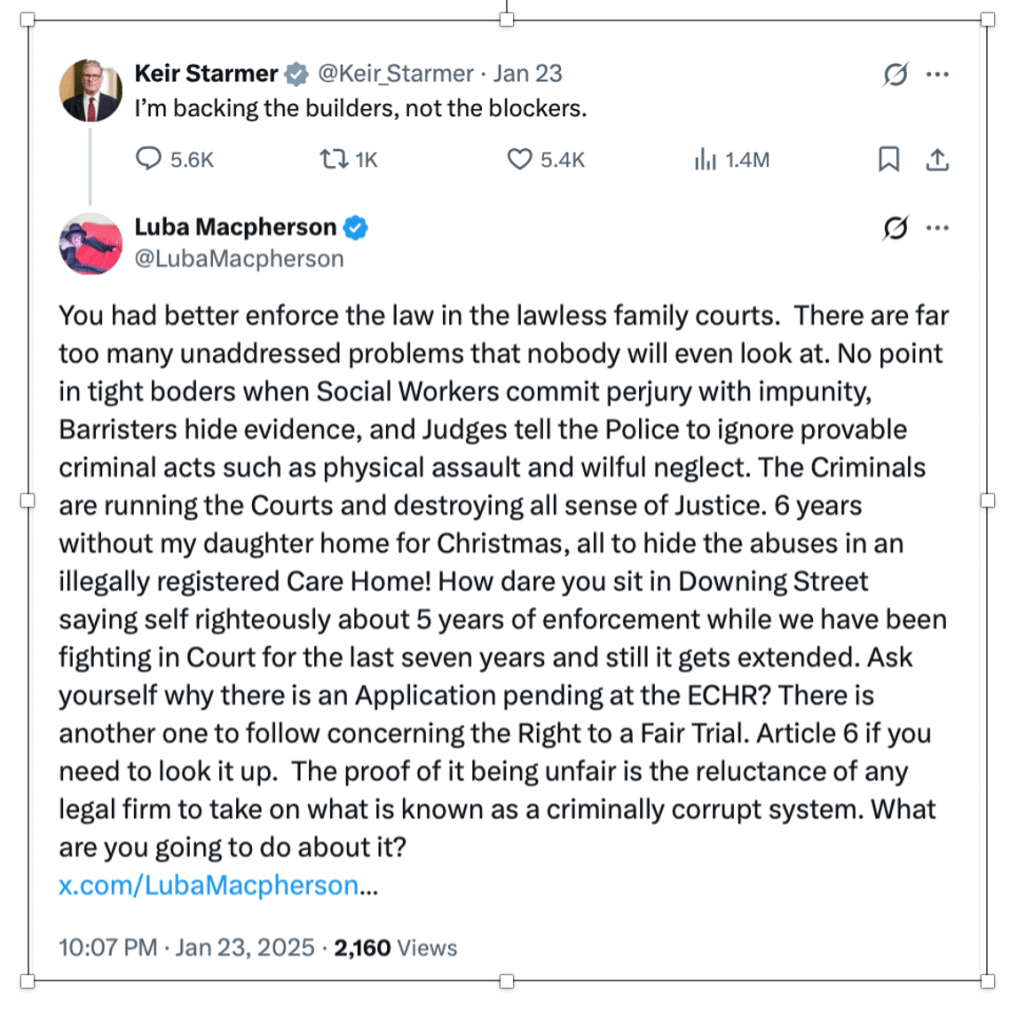

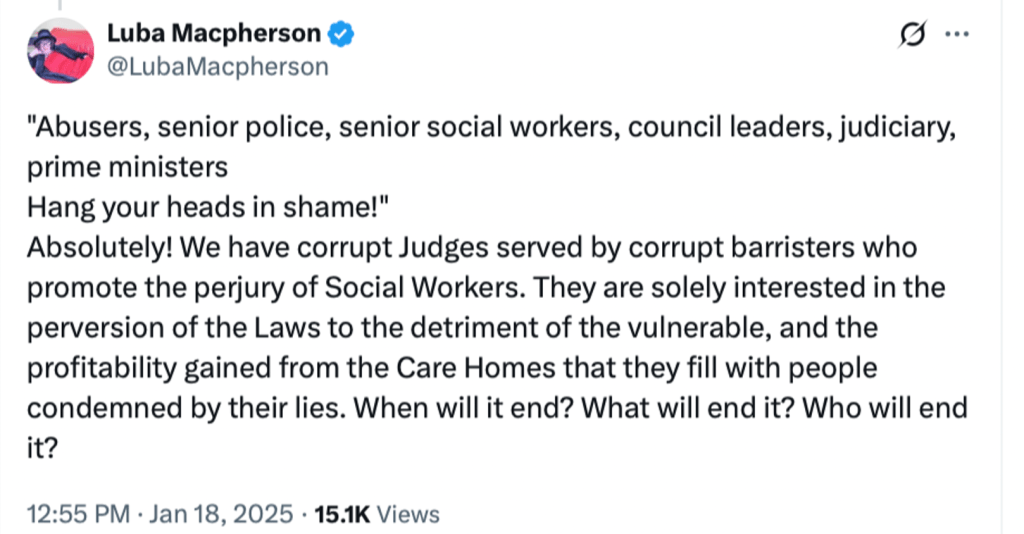

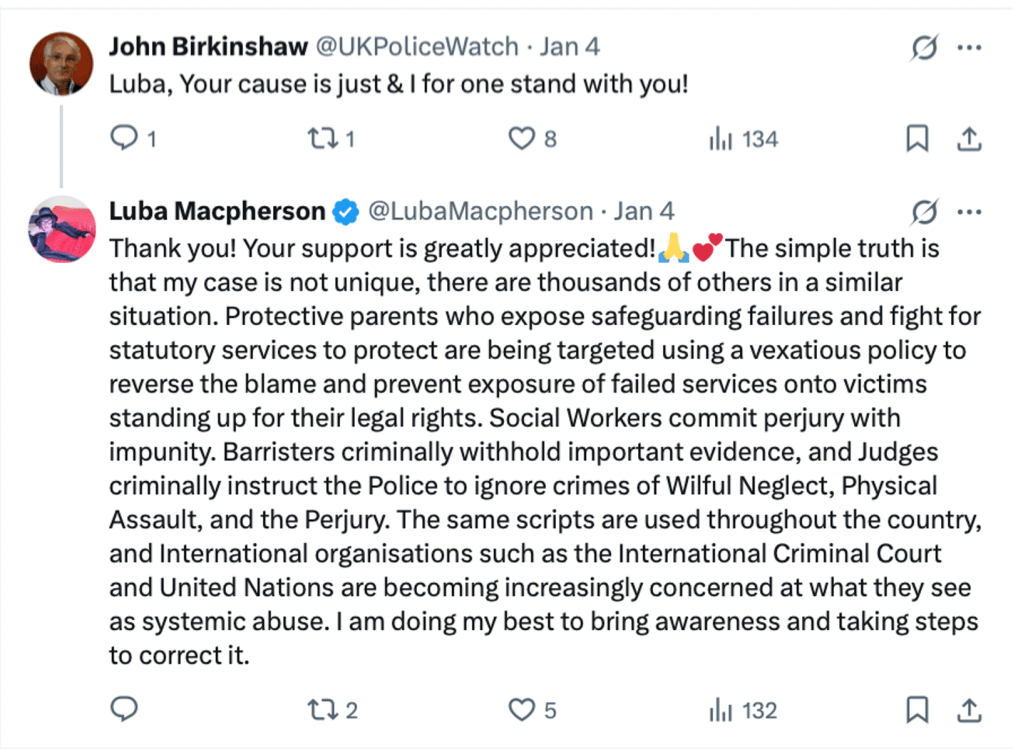

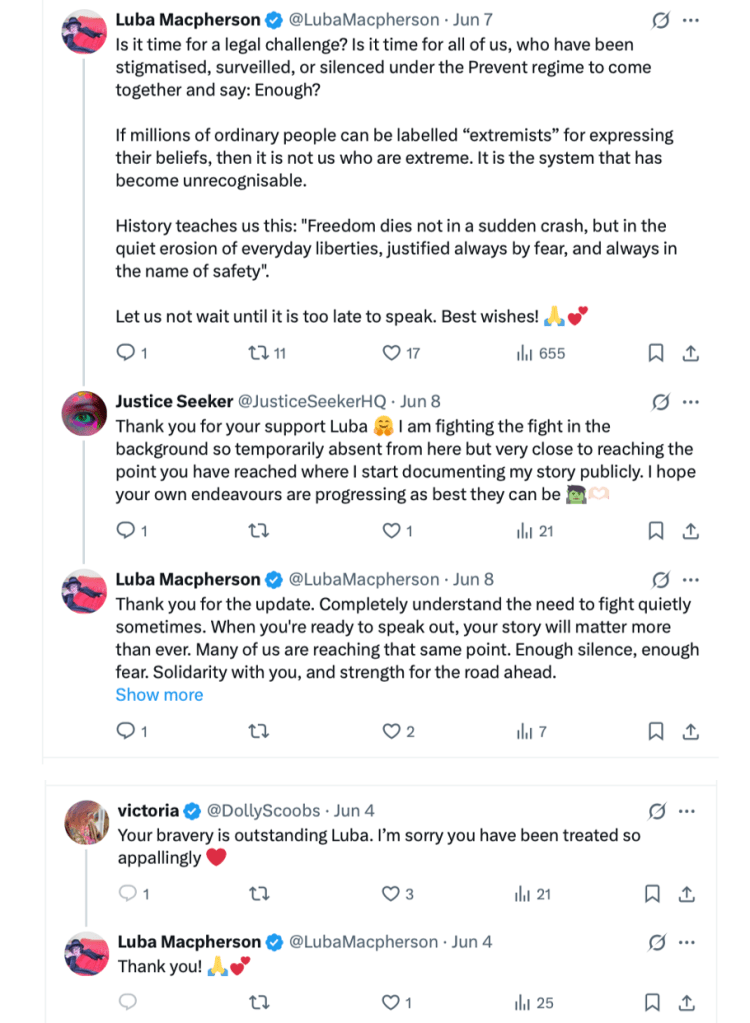

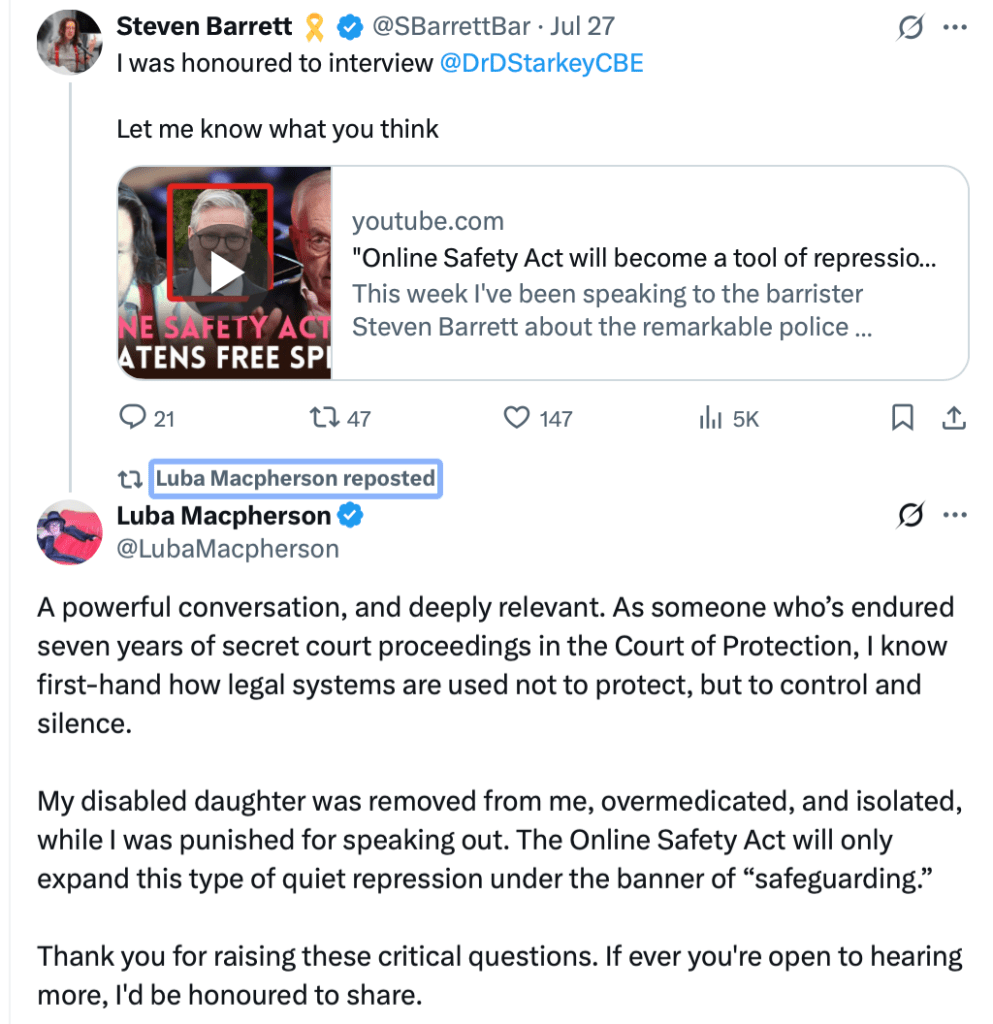

She has posted prolifically on social media about her outrage regarding the entire court, health and social care system – and she’s developed networking skills to build links with other justice campaigners and has attracted many supporters (see sample social media posts below).

Views like Luba’s are shared by others and are, arguably, more likely to form in response to situations and systems in which people feel controlled or find themselves positioned on the ‘wrong side’ with powerful state agencies in opposition to them.

Many individuals and families feel similarly to Luba and believe that our statutory systems of health and social care, and the justice system, do not properly listen to them, pathologise their beliefs and values, or blame them when they complain, campaign or enter into (persistent) disputes with those systems of care.

In July 2021, Leeds University published a report – Institutionalising parent carer blame – which – although referring to parents of disabled children (Luba’s daughter is an adult) – has relevance in general to how parents might be cast when there are disputes with statutory agencies. The report says that:

‘National and local social care policies in England create a default position for those assessing disabled children, that assumes parental failings. This approach locates the problems associated with a child’s impairment in the family – a phenomenon referred to in this report as ‘institutionalising parent carer blame’ ‘(para 1.04).

I have observed other cases – most notably that of Laura Wareham (see this blog for example: ‘The point is this – she is scared and vulnerable’: Judge about Laura Wareham) – where families are at loggerheads with services and are cast as vexatious or unreasonably ‘persistent’ in their complaints about health and social care bodies, which in itself can then be seen as the problem. As the Leeds University report says, problems associated with the child’s difficulties can often be ‘located’ in the family.

That is not to say that families (or family members) are never abusive or neglectful (or both) to their relatives. That would be an obviously nonsensical position to take. However, I would assert that most families, most of the time, aim to do what they think is the best thing for their relatives. And they also, often, know best the person receiving care, and have the biggest investment in their wellbeing as a loved family member. When their views on what is best differ from those of services, the significant power imbalance (between the system and those on the receiving end) often becomes evident, arguably with those at the ‘powerful’ end employing their arsenal in efforts to exert control, dominance and ‘expert’ clinical or legal authority.

Such power dynamics might not always even be in response to purported wrongdoing on the part of relatives. In a very recent blog (“Perhaps the most contentious matter is the question of his social media and internet access.” But who is the decision-maker?) about a long-running case concerning a young man, XY, whose family members are deputies for his care decisions, there was a sudden and unexpected ‘veiled threat’ from the judge regarding the court’s powers to revoke deputyships, despite there never having been a suggestion that this particular family was acting in any way improperly. Daniel Clark notes:

“As far as I am aware, no party is suggesting that XY’s deputies are acting other than in his best interests. […]

The fact that the judge chose to go down this path left a sour taste in my mouth. It seemed to be a thinly veiled threat that proceeding with the application runs the high risk of the deputyship being revoked.

Of course, what the judge was saying is technically true. The court can, of its own motion (without being asked), make an order that it considers to be proportionate and necessary. One of those orders is the revocation of a deputyship.

This, however, misses the point.

Given the fact that this was not foreshadowed, the exchange felt more like a hostile assertion of asymmetric power dynamics. The not-so-implicit message was, “I have the power here – don’t get on my wrong side”. That it was directed (through counsel) at family members was shocking enough. From what I’ve seen, the family have only acted in XY’s best interests (including issuing these proceedings in the first place). This made it even more shocking.”

There are a lot of people who feel wronged by our statutory systems, and many say so loudly on social media. And of course, there will be many people who work in those systems who, individually, try their best and aim to do a good, person-centred job, but when there are multiple agencies and systems of control, decision-making and care interacting and trying to work together (or not) the effects on people and their families who need those systems the most might not be experienced as benign and compassionate, let alone fair.

Although those (in the ‘system’) who disagree with them might describe their views colloquially as “unhinged” or as “wild conspiracy theories” or “delusions”, this does not translate into a medical or mental health diagnosis of the kind that might qualify as an “impairment of, or a disturbance in, the functioning of the mind or brain” for the purposes of finding a lack of capacity. And further, ‘persistence’ in itself does not necessarily mean that the person is wrong about whatever they are persistent about. For embattled systems of care and courts with enormous backlogs, it’s possible to see how those ‘persistent’ people (and I do not mean those who are truly abusive to those they care for) can be framed as the problem, rather than the systems they are caught up in. Systems are made up of people, and people (in general) don’t like to be criticised, stood up to or made demands of. Arguably, however, ‘people’ making up our statutory care systems are in exactly the roles where those experiences should be expected (even welcomed) with equanimity, even when we are (individually) ‘trying our best’ and intentions are good.

How did it come about that Luba’s capacity to litigate was questioned? Perhaps this wider cultural context can offer some understanding of how systems can respond to experiences of significant challenge.

2. What is meant by ‘capacity to conduct proceedings’ and how was this applied in Luba’s case?

In her judgment determining that Luba Macpherson had litigation capacity, Mrs Justice Theis referred to a recent (2025) case heard by the Court of Appeal (I’ll call it the ‘Johnston case’):

§27 The case law regarding capacity has recently been set out by Baker LJ in Johnston at [38] – [43]. That was a case that involved capacity to conduct current and past proceedings. He referred to the two stage test in A Local Authority v JB [2021] UKSC 52 at [66 – 79]. The first question to be asked is whether P is unable to make a decision for himself in relation to the matter. If so, the second question is whether the inability is because of an impairment of, or a disturbance in the functioning of the mind or brain. The second question ‘looks to whether there is a clear causative nexus between P’s inability to make a decision for himself in relation to the matter and an impairment of, or a disturbance in the functioning of, P’s mind or brain’. The Supreme Court was clear at [79] that the two question [sic] should be approached in that sequence.

So, capacity to conduct proceedings must be presumed. It’s displaced if, on the balance of probabilities, the evidence is that the person is not able to understand, retain, weigh, and communicate the information relevant to the decisions that need to be made in order to conduct proceedings – and if that inability is caused by an impairment or disturbance in the functioning of the mind or brain.

The test of capacity needs to be applied in that order – first the functional test (can the person understand/retain/weigh/communicate the relevant information?), then the diagnostic test (is the inability caused by an impairment or disturbance in the functioning of the mind or brain?)

So, what does a person need to understand/retain/weigh in relation to determining litigation capacity? In the Johnston case, the judgment records:

§40…. the leading common law authority on capacity to conduct proceedings was Masterman-Lister v Brutton and Co and another [2002] EWCA Civ 1889 in which Chadwick LJ said, at paragraph 75: “For the purposes of … CPR 21 – the test to be applied, as it seems to me, is whether the party to legal proceedings is capable of understanding, with the assistance of such proper explanation from legal advisers and experts in other disciplines as the case may require, the issues on which his consent or decision is likely to be necessary in the course of those proceedings.”

What might be the ‘issues on which his consent or decision’ are necessary? The GOV.UK Certificate: Capacity to Conduct Proceedings states:

‘To have litigation capacity the party or intended party must:

• be able to understand the information relevant to the decisions arising during the course of the proceedings (including legal advice); this means being able to understand with the assistance of such proper explanation from legal advisors and experts in other disciplines as the case may require, the issues on which their consent or decision is likely to be necessary in the course of those proceedings.

• be able to retain that information for long enough to make a decision about it,

• be able to use or weigh that information as part of the process of making the decisions, and

• be able to communicate their decision (whether by talking, using sign language or any other means) – this is intended to apply to those who are unable to communicate at all, for example because they are unconscious or in a coma.Please note:

• legal proceedings are not simply a question of providing instruction to a lawyer and then sitting back and observing the litigation, but rather a dynamic transactional process, both prior to and in court, with information to be recalled, instructions to be given, advice to be received and decisions to be taken, potentially on a number of occasions over the span of the proceedings as they develop;

• the information relevant to the conduct of the proceedings includes the reasonably foreseeable consequences of deciding one way or the other, or failing to decide at all;

• a person should not be held to be unable to understand if they can understand an explanation of the relevant information in broad terms and simple language;

• a lack of capacity cannot be established merely because of a person’s age or appearance or their condition or an aspect of their behaviour.The relevant information which a party or intended party would need to be able to understand, retain and use or weigh may include:

(a) how the proceedings are to be funded;

(b) the chances of not succeeding and the risk of an adverse order as to costs;

(c) the sorts of decisions that may arise in the litigation;

And: ‘Capacity to conduct the proceedings would include the ability to give proper instructions for and to approve the particulars of a claim, and to approve a compromise. To be able to approve a compromise, a party or intended party would need insight into the compromise, an ability to instruct solicitors to advise them on it, and, if solicitors are instructed, an ability to understand and weigh their advice.’

How might these requirements have applied in Luba’s case?

First the functional test. In her judgment, Theis J quotes Baker LJ from the Court of Appeal hearing for Luba on December 3rd 2024:

“So far as the functional test found in section 3 of the Mental Capacity Act is concerned, Dr Prabhakaran concluded that there was no evidence to suggest that the Appellant could not understand or retain information but that: “due to her firmly held beliefs which persist despite evidence against these, on balance, her ability to use and weigh up information relevant to the court proceedings is likely to be affected as a result”. Therefore, he said, on the balance of probabilities she was “unable to make decisions regarding the conduct of these proceedings“.

So, the expert psychiatrist’s view rested on the assertion that Luba lacked the relevant capacity to ‘use and weigh up information relevant to the court proceedings’. In an interesting (2012) paper (‘Unreasonable reasons: normative judgements in the assessment of mental capacity’) the author argues the following in relation specifically to ‘weighing’ information:

“The major conceptual flaw in cognitive accounts of capacity is that underpinning the assessment of the descriptive criteria for capacity is an intrinsically normative judgement. Specifically, assessing the criterion of using, weighing or balancing information involves the clinician making a judgement that hinges upon whether the patient is appropriating and using the information given in the way that he, in a sense I will seek to clarify, ought to. Importantly, this sense of how the patient ‘ought to’ use information is open to interpretation by clinicians, and it is my contention that this is what gives rise to disagreement in difficult cases”

In the conclusion, the author says “I suggest that clinical judgement is enhanced by recognizing that it involves navigating a complex encounter in which clinicians play an active role, not as impartial observers of cognitive functioning but as participants in judgement guided by normative assumptions about what it means to engage successfully in a decision-making process.” This is the opposite of a belief that capacity for a decision is a fixed entity and resides ‘in’ a person; instead framing ‘capacity’ as a dialogical process, which I think was the spirit of the MCA 2005 which emphasises the importance of facilitating understanding as much as feasibly possible, and truly accepting different values and beliefs.

In relation to the diagnostic test for Luba, Dr Prabhakaran’s evidence was that “on the balance of probabilities the information available suggests the “possibility of a delusional disorder”.’ (Court of Appeal, quoted in Theis J judgment §17)

Given the complexities of assessing capacity, I wonder whether Luba being judged (in a paper-based assessment) as not weighing up and using the relevant information in a normative way (as she ‘ought to’) contributed to the conclusion of a delusional disorder.

The Court of Appeal then made an interim declaration that the Court had ‘reason to believe that the Appellant lacks capacity’, referring the determination on litigation capacity back to the Court of Protection. Theis J, in her Court of Protection judgment, was clear:

One of the submissions advanced to evidence Luba’s lack of litigation capacity (from Oliver Lewis, who – at the litigation capacity hearing before Mrs Justice Theis on 30th April 2025 – represented Luba via the Official Solicitor at the invitation of the Court of Appeal) related to her ‘persistent’ attempts to reopen the case regarding her daughter. The judgment states:

However, Theis J. found that the making of repeated applications does not demonstrate lack of capacity. In this paragraph [§56 (6)] of the judgment, she says:

“I have weighed in the balance the point made by Mr Lewis that Ms Macpherson has continued to make applications. That is not unusual behaviour with litigants who, like Ms Macpherson hold strongly held beliefs. It does not equate with lack of capacity on its own and can be managed by the court through the exercise of appropriate case management powers.”

Indeed. There are very many people who believe that justice is not being carried out, and for some it can feel like a life-or-death situation for them or the people they love, or a cause that they believe in passionately. Why shouldn’t they take advantage of a legal system which allows them to ‘persistently’ pursue their concerns? And to ‘equate with lack of capacity’, as Mrs Justice Theis states above, is curious. In whose interests would it be useful to equate multiple applications with lack of litigation capacity? Luba has become quite an inconvenience for the court and she won’t be silenced – if she were deemed to lack mental capacity to litigate, the optics would be very different. It is perhaps tempting to pathologise someone whose views are simply not shared by ‘the system’, and who will go to the ends of the earth to make their case and have it heard to their satisfaction. That doesn’t mean, though, that they lack the capacity to make that case.

3. Concerns about Luba Macpherson’s behaviour and conduct earlier in the proceedings

Theis J acknowledged that Luba’s “behaviour and conduct” (§53) had been described in various judgments, by different judges, over the years before January 2024, in ways that clearly show the judge(s) were concerned with how Luba was engaging with court proceedings. At first, largely in relation to the way her behaviour affected her daughter (HHJ Moir), then with additional concern about Luba’s own mental health status (Poole J) and latterly with the focus on Luba herself (Theis J). But none of the judges (or lawyers, including her own legal representatives when she had them), at those moments in time, explicitly suggested that this was evidence that she might lack litigation capacity.

In her judgment dated 21st October 2020, HHJ Moir made findings that Luba lacks “a basic understanding” of her daughter’s mental illness and communicates “negative critical thoughts” to her in sometimes “abusive” terms. She “attempts to challenge FP’s medication and has interfered with FP’s medication to the detriment to FP” (§29). The judge reported that Luba was said to “regularly disregard professional advice and standards. [She] constantly challenged health advice and instruction from professionals designed to promote FP’s wellbeing” (§46) and has been “obstructive” (§47). ‘FP’ are the initials given to Luba’s daughter in the judgments.

In the earlier judgments, Luba is anonymised as “RT”, which I have replaced with “Luba” in the quote below to help the reader.

Noting “in court that [Luba] could become very agitated and voluble” (§113), HHJ Moir says in her (2020) judgment:

“§81 In her oral evidence before me, [Luba] made her views clear. She told me: ‘FP has been tortured and abused for years’, that the fluctuation in FP’s mental state was because her medication was not properly reviewed. [Luba] referred to the conspiracy between the doctors and the nurses to experiment with FP’s medication. She told me the Social Services influenced the hospital:

“The social worker interferes, tittle tattle again, turning the nurses against me. I’ve been through so much. They are just bullies. They put me through daily stress. I have been deliberately aggravated. I have been excluded. I have had aggravation since day one. I don’t know why. Statements by the social workers are not accurate; they are just not. They are a lot of lies. I just try my best for my daughter. I have not done anything wrong”.

There is no recognition of the effect her behaviour has upon other people, including FP, or any acceptance of any responsibility for the distress occasioned to FP by reason of the high expressed emotion, referred to by Dr Ince, on [Luba’s] behalf.”

After HHJ Moir’s retirement, the case was heard by Mr Justice Poole.

By 2022/2023, the focus of hearings had shifted from concerns about Luba’s contact with her daughter (which had led the judge to make contact restrictions) to the fact that – in contravention of an order forbidding her from doing so – Luba was posting videos and photographs of her daughter on social media (sometimes apparently also featuring the care staff) and publicly naming her daughter. Although Luba was posting this material as part of her campaign to demonstrate how her daughter was being harmed by professionals, the judge’s view was that these published recordings “disclose conduct that is harmful to FP. The Defendant manipulates conversations with her vulnerable daughter and feeds her the line that she is being harmed by those caring for her and by her medication. Since FP has paranoid schizophrenia and believes she is being persecuted, the line fed to her by the Defendant is particularly dangerous to the mental health of her daughter” (§54 Poole J’s January 2022 judgment [3])

In his judgment from the committal hearings (dates: 8th December 2022 and 16th January 2023, at which Luba was represented by Oliver Lewis), Poole J also raised the issue of Luba’s capacity:

“§16 On 8 December 2022 I indicated that I would adjourn for approximately one month before considering sentencing of the Defendant. I asked whether Ms Turner [I think she’s the instructing solicitor] sought any reports on the Defendant prior to sentencing but she said not. I had in mind the possibility of the court receiving medical evidence about the Defendant if that might be relevant to sentencing. Ms Turner was satisfied that her client had capacity to give instructions. Mr Lewis representing the Defendant today, on 16 January 2023, has not sought any capacity assessment of his client nor any medical reports.” [my emphasis]

As in the earlier judgments before HHJ Moir, this (more senior) judge raised concerns about Luba’s mental health in his 22nd January 2024 judgment:

“§6 […] I have a long experience of Ms Macpherson appearing before me remotely and she can become angry and unfocused.[…]

§31 […] The defendant has continued to resist all suggestions that she might require medical assessment. She regards such suggestions as a feature of the conspiracy against her and her daughter.”

Theis J’s final determination in relation to any evidence that Luba lacked litigation capacity, either then or previously, was as follows:

§54 Whilst it is important in this wide canvas to consider that assessment of capacity is both time and decision specific, and I fully recognise and factor in the dynamic nature of the decisions involved in assessing litigation capacity, as detailed in the letter of instruction, but it needs to be in the context of understanding the salient features. I can’t ignore the evidence that in each of these hearings Ms Macpherson has been able to conduct them either with the assistance of legal representation or not with what has been described as her misguided and entrenched opinions. It is right that her behaviour has been difficult and, at times, difficult for the court to manage (such as described by King LJ in the Court of Appeal) but that does not and should not be used against her in assessing capacity to conduct the proceedings now or in January 2024. Many litigants can be difficult to manage in hearings or within proceedings, and often express very strongly held views about one or more aspects of the proceedings. In many cases that type of behaviour can be managed by effective and proportionate case management, such as limiting the length of any documents submitted, the volume of any documents in a court bundle, the time for any submissions, to ensure any parties’ right to a fair trial protected by Article 6 of the European Convention on Human Rights are respected within the confines of what is relevant and proportionate to the issues being determined by the court. This accords with the overriding objective in the relevant procedural rules. In these proceedings it is rule 1.1 Court of Protection Rules 2017. In assessing litigation capacity it is important not to conflate this type of behaviour, coupled with strongly held views as evidence of lack of capacity. Each situation is, by definition, very fact specific.

Vital points, in my view, from that paragraph are:

- “It is right that her behaviour has been difficult and, at times, difficult for the court to manage […] but that does not and should not be used against her in assessing capacity to conduct the proceedings now or in January 2024”, and

- “In assessing litigation capacity it is important not to conflate this type of behaviour, coupled with strongly held views as evidence of lack of capacity.”

So, difficult and annoying litigants are not the same as incapacitous litigants!

4. The Protection Imperative?

“The court must avoid the “protection imperative” – the danger that the court, that all professionals involved with treating and helping P, may feel drawn towards an outcome that is more protective of her and fail to carry out an assessment of capacity that is detached and objective” CC v KK [2012] EWHC 2136 (COP), Quoted at §39 of Theis J’s judgment, see also 39 Essex Chambers’ report on the 2012 case here]

In a 2019 International Journal of Law and Psychiatry paper, entitled ‘Taking capacity seriously? Ten years of mental capacity disputes before England’s Court of Protection’, Alex Ruck Keene et al. explained Baker LJ’s CC v KK judgment further:

“In this case Baker J synthesised observations made by other judges in a number of cases, and emphasised that: the roles of the court and the expert are distinct and it is the court that makes the final decision as to the person’s functional ability after considering all of the evidence, and not merely the views of the independent expert; professionals and the court must not be unduly influenced by the “protection imperative”; that is, the perceived need to protect the vulnerable adult; the person need only comprehend and weigh the salient details relevant to the decision and not all the peripheral detail. Moreover, different individuals may give different weight to different factors; and capacity assessors should not start with a blank canvas: “The person under evaluation must be presented with detailed options so that their capacity to weigh up those options can be fairly assessed” (CC v KK, para 68).[4] These cases illustrate that, even when P has a diagnosed mental disorder, judges may override expert psychiatric opinion on capacity, thus firmly establishing that it is not mental disorder or impairment that is dictating the judgment.”

The following quote from Poole J’s committal hearing judgment demonstrates that the court seemed not to want to send Luba to prison:

“§58 In this case the Defendant has almost dared the court to send her to prison because she believes it will bring attention to her bizarre views. However, to imprison the Defendant could well cause harm to others, both to the Defendant’s husband, FP’s stepfather, who has health issues and is aged 74 and who is looked after at home by the Defendant, and to FP herself. It seems to me very likely that FP would learn that her mother had been imprisoned by the court. The evidence of Mr Salmon shows that by whatever means, FP has been informed of the committal proceedings. It is very likely that FP would be informed if her mother was indeed imprisoned, and this would be upsetting to FP whose mental state is of course fragile. The knowledge that the Defendant had been imprisoned would risk exacerbating FP’s paranoia and fear of persecution. Her understanding of why she has been removed from her mother appears to be limited. Her understanding of why her mother had been imprisoned may well also have limitations. I have to bear in mind that imprisoning the Defendant could well do FP more harm than the breaches themselves.”

At a recent webinar hosted by Kings Chambers (Current and retrospective litigation capacity: revisited by the Court of Appeal and Court of Protection – 26 June 2025), which reviewed Luba’s case and the topic of litigation capacity, a consultant psychiatrist (Dr Faisal Parvez) discussed what is widely known as the ‘protection imperative’ [quote from my notes]:

“As doctors, we often try and protect people. And either rightly or wrongly, it may have been felt that, in this case, LM [Luba] might end up in prison, she might end up with a really harsh sentence, and actually if she didn’t have capacity that might mean that she [receives (?)] less in terms of sentencing, that the court might be more sympathetic to her in some way and the repercussions might be less. That’s a real challenge for us as clinicians because all throughout our training you’re taught that your primary concern is the patient, if you like – or the person that you’re seeing or assessing. So, in some ways, you try and advocate for them as best as possible.”

The same thoughts had occurred to me. I have wondered whether the system might have taken the ‘protection imperative’ route, described above by Dr Parvez.

It also doesn’t seem irrelevant to consider that the context, at this point, was that Luba had been found to be in contempt of court, already had a suspended sentence, and by continuing in contempt of court it was almost inevitable that an immediate custodial sentence would have to be imposed. Could it be possible that, as a system around Luba and her daughter, the court became embroiled in the ‘protection imperative’ (even unconsciously, to get out of its pickle of facing having to send Luba to prison, which it really did not want to do)? Who is the object of protection here is perhaps arguable.

It is clear from Poole J’s judgment, quoted earlier, that the court really did not want to imprison Luba because that would be inimical to the purposes of the CoP: P’s best interests, i.e. in this case, the best interests of Luba’s daughter. One way out for the courts to avoid sending Luba to prison (and distressing her daughter by doing so – the very person that they are there to protect) would be to find that Luba did not have the requisite capacity. No such decision could have been made in accordance with the law of course, because as Peter Jackson J memorably pointed out in Heart of England NHS Foundation Trust v JB (2014):

‘The temptation to base a judgment of a person’s capacity upon whether they seem to have made a good or bad decision, and in particular on whether they have accepted or rejected medical advice, is absolutely to be avoided. That would be to put the cart before the horse or, expressed another way, to allow the tail of welfare to wag the dog of capacity. Any tendency in this direction risks infringing the rights of that group of persons who, though vulnerable, are capable of making their own decisions.’ But we are all human (even lawyers) and I can understand the temptation to adopt that approach. It would certainly be wrong to imprison someone on the basis of an unjust trial at which they’d been wrongly presumed to have capacity to litigate.’

In an earlier blog about this same case (A committal hearing to send P’s relative to prison – and the challenges of an in-person hearing) from 8th February 2023, I wrote: “ … I am left wondering whether Sunderland City Council would do anything differently, were they able to rewind the clock and do it all again. Listening to the reasons for not incarcerating Luba (mainly so as not to distress FP, as well as enabling her (Luba) to continue to care for her husband) I couldn’t really understand why the recordings (and their publication) had been part of the injunctive order. FP did not know (or the court thought she did not know) about the recordings – she therefore did not know they had been posted online. That is not to say it wasn’t an intrusion into her right to privacy (Article 8 rights), though Luba would contest that claim: she believes that FP [Luba’s daughter] has capacity to decide to be recorded and share those recordings and that FP had consented. What seemed more harmful to FP though (from the Council’s perspective) was Luba’s influence and what they described as ‘manipulation’ of FP. It felt as if they had got themselves into a pickle over the recordings when maybe it is the contact (i.e. the actual experience of FP) that should be the focus. Luba was still allowed contact with FP, and I couldn’t understand how threatening Luba with jail would foster a situation where she might temper her conversations with FP? Surely it is more likely to inflame her views and become more entrenched in her position.”

And Poole J’s judgment had confirmed that he did not judge the social media posts to be harmful to FP:

“§54 However, it is the conversations themselves that are most harmful to FP, not the posting of recordings of those conversations online. I have seen no evidence that FP is herself aware of the fact that her conversations have been shown to others by publication online. FP may not even be aware that her telephone conversations have been recorded. She will be aware that she was filmed being “interviewed” by the Defendant but there is no evidence that she knows what the Defendant did with that film. Accordingly, I proceed on the basis that there is no evidence that the admitted breaches have caused FP harm.”

I still wonder why Sunderland City Council chose to include the social media posting in their case. The fact that they did has resulted in the enormously protracted and expensive appeal and capacity litigation, which is still not concluded. This is not to mention how stressful it must be for Luba, and surely less, not more, likely to result in a collaborative or measured way forward. And, still, the very real possibility that Luba will be put in jail – most definitely not the outcome that the court wants.

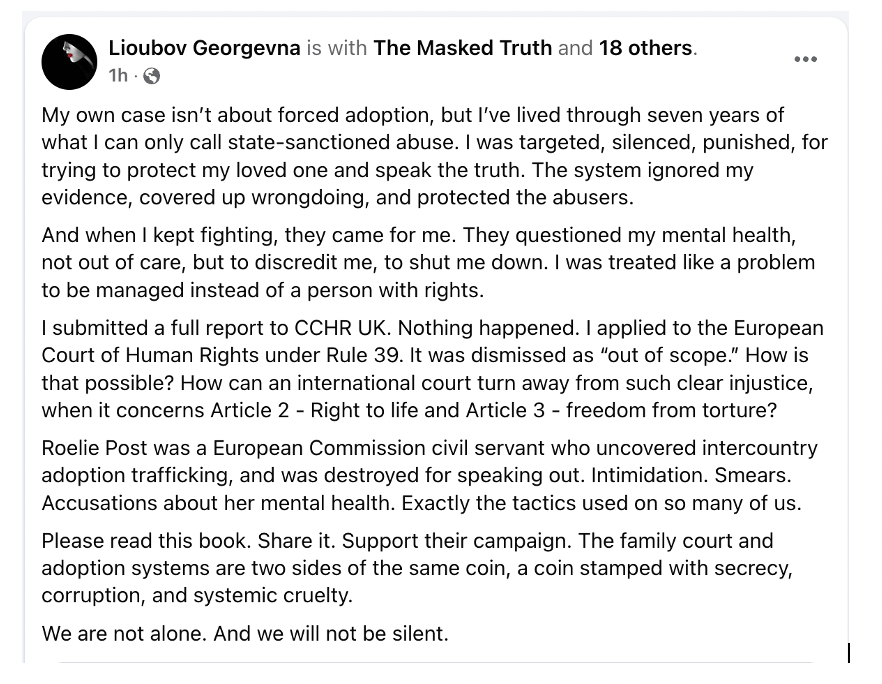

In this context it is possible to understand why Luba believes ‘And when I kept fighting, they came for me’ (below, Facebook post 14th June 2025):

Whatever the genesis of the question about Luba’s litigation capacity – I would suggest that what has happened, and her sense of vindication now that the presumption of her capacity has been confirmed, has entrenched, rather than ameliorated, her beliefs about the authorities being out to get her. It’s made it less, rather than more, likely that she will desist from posting on social media, and less likely that she will collaborate with the ‘system’ in any other way.

And now, of course, in that context, the court is back to the matter of whether Luba’s appeal against her prison sentence is upheld.

Reflections

Another way of looking at this is to consider what we want ‘litigation capacity’ to mean in practice. I wonder whether many of us could really understand, retain, weigh and communicate all legal aspects of our case sufficiently to instruct a lawyer or to act as litigants in person. The matter of where to draw the line between capacity and incapacity depends on what level of involvement and competence is considered adequate.

Definitions and understanding of ‘capacity’ can and do develop over time: an example is the decision of the Supreme Court in Re: JB A Local Authority v JB (by his litigation friend, the Official Solicitor) [2021] UKSC 52:

At §121 in the Supreme Court judgment it is clarified that, in law, in assessment of the capacity requirement for sex, ‘information relevant to that decision includes’ (1) ‘the fact that the other person must have the ability to consent to the sexual activity’ and (2) ‘the fact that the other person must in fact consent before and throughout the sexual activity’. This meant that a proportion of people previously deemed to have capacity to consent to (or engage in) sex were now deemed to lack that capacity.

Likewise, arguably the definition of “capacity to litigate” can be made more or less stringent, and can involve a requirement to understand, retain, and weigh, more (or less) information. A finding that Luba Macpherson lacked capacity to litigate would have undoubtedly had implications for many other family members who act as parties to CoP cases, since the bar for litigation capacity would have been set relatively high. The finding that she has capacity to litigate is in this sense unsurprising, since there are serious human rights implications in setting such a high bar that would disqualify many more people – including many family members of protected parties – from the right to instruct a solicitor or to represent themselves in court.

Claire Martin is a Consultant Clinical Psychologist, Cumbria, Northumberland, Tyne and Wear NHS Foundation Trust, Older People’s Clinical Psychology Department, Gateshead. She is a member of the core team of the Open Justice Court of Protection Project and has published dozens of blog posts for the Project about hearings she’s observed (e.g. here and here). She is on X as @DocCMartin, on LinkedIn and on BlueSky as @doccmartin.bsky.social

Footnotes

[1] Luba is content for us to use her shortened first name for the purposes of our blog

[2] I didn’t observe the hearing before Mrs Justice Theis on 30th April 2025, or the judgment being handed down on 22nd May 2025, but I’ve observed previous hearings in this long-running case (including – in person – the committal for contempt hearing on 16th January 2022, at Newcastle Court, blogged here; (remotely) the appeal hearing against that committal, on the 4th May 2023, which Celia Kitzinger attended in person at the Court of Appeal; and another (remotely) regarding further alleged breaches of court orders on 4th December 2023, blogged here by Amanda Hill).

[3] On BAILLI this judgment is dated 20 January 2022. I think this is a typo and it should, I believe, say 2023, because it relates to hearings on 8th Dec 2022 and 16th Jan 2023)

[4] Two other relevant cases (concerning medical disagreement and insight in relation to mental capacity) are described by Alex Ruck Keene in his blog ‘Capacity, insight and professional cultures – an important new decision from the Court of Protection’

Have sent feedback to Bailii re the incorrect date at the top right of [3]

LikeLiked by 1 person

Re: “Litigation Capacity, Luba Macpherson and the court’s engagement with a ‘persistent’ litigant”

Thank you very much, Claire, for your thoughtful and compassionate analysis, especially your reference to the duty of lawyers under the SRA Code to act when capacity is questioned. But it’s precisely here that I believe the process in my case became deeply flawed. My lawyers claimed to be fulfilling their professional duty, yet failed to act on key legal authorities that protected my right to freedom of expression and to a fair trial.

In particular, I refer again to the guidance set out in judgments by Lord Burnett of Maldon, the former Lord Chief Justice, where Article 10 of the European Convention on Human Rights was given proper weight, even in family or sensitive proceedings. Lord Burnett has made it clear that transparency is essential, especially where individuals allege serious injustice and public interest disclosure is at stake. In my case, my legal representatives failed to raise such precedents, even when I was explicitly arguing that secrecy was being used to cover up misconduct and violations of my daughter’s and my rights.

As you rightly say, there is a legal and ethical duty to consider a client’s “attributes, needs and circumstances.” But what about my need to expose abuse? My right to lawful protest? My express instructions to pursue justice through legal means, not psychiatric silencing? A paper-based psychiatric assessment was authorised, without my participation, while no equivalent weight was given to my legal arguments, or to applicable case law on Article 10. How can that be right?

The short answer is, it’s not. Not legally, and not ethically. It was a form of procedural dispossession, in which my identity as a campaigner and carer was reframed as evidence of mental disorder, simply because my views did not align with those of the state.

And when you write that I was “frequently told by judges” that I was interrupting or speaking about irrelevant matters, I would suggest a different framing: I was insisting that the real issues — systemic abuse, judicial secrecy, and violations of my daughter’s rights — be heard. The fact that those issues were repeatedly sidelined is not proof of my incapacity, but rather of the system’s refusal to engage with the inconvenient truth I was trying to speak.

The entire detour into litigation capacity has been, for me, a frustrating, unjust, and unnecessary diversion from the real matter at hand: my appeal against a prison sentence imposed for trying to protect my daughter. That detour not only delayed justice, it reframed my pursuit of justice as a symptom of mental disorder.

And yet, thanks to Claire Martin and the Open Justice team, some clarity and balance have emerged from this experience. Her blog has helped to document and expose the deeper questions I’ve been raising for months, questions which remain unanswered by the very system that claims to uphold fairness and transparency.

One of those questions is this: Why did the Court of Appeal appoint the Official Solicitor to represent me as a protected party without notifying me, involving me, or following any visible due process? That decision altered the course of my appeal. I was sidelined from my own case, without explanation, and without being given a chance to object. That is not how justice should function in a democratic society.

Another unaddressed issue is the behaviour of judges themselves. In court, I’ve been repeatedly accused of interrupting, but no one has examined the interruptions directed at me — the dismissive tones, the cutting off mid-sentence, the refusal to acknowledge the evidence I was trying to raise. If I sometimes reacted emotionally, it was not because I lacked capacity, it was because I was being provoked, silenced, and stripped of my role as a mother and advocate.

Capacity has been used, in this context, as a shield against accountability, a tool to reframe dissent as disorder, persistence as pathology. That should concern everyone. Because if it can happen to me, it can happen to anyone who challenges authority from a vulnerable position.

I’m grateful for your careful unpacking of the functional test for capacity, and especially for quoting Dr Prabhakaran’s conclusion as presented to the Court. But I must challenge the formulation he relied on — and that the Court repeated without proper scrutiny:

My question is simple: What evidence and what about my evidence?

This phrase is clinically loaded and legally consequential, yet nowhere does the psychiatrist specify exactly what the “evidence” against my beliefs actually is. Was it medical evidence? Judicial findings? Social work reports? If so, were those documents ever tested, cross-examined, or weighed in accordance with due process? Or was this just an echo chamber of unchallenged assumptions, repeated by professionals with power?

Persisting in one’s beliefs is not incapacity. Refusing to adopt the views of professionals, especially when those professionals are part of a system one is challenging is not a mental disorder. As Theis J rightly pointed out, strongly held beliefs do not equate to lack of capacity, and repeated applications do not equate to delusional persistence.

In my case, I wasn’t “resisting evidence” — I was resisting untested claims, some of which were later disproved or admitted to be flawed. To frame that as an incapacity to weigh information is deeply dangerous, not just to me, but to anyone who raises concerns about the conduct of courts, care homes, or mental health systems.

It cannot be acceptable for a capacity assessment to rely on unspecified and untested “evidence” as justification to override a person’s agency in legal proceedings. That is the very antithesis of justice.

With respect to the submission described at §34, that I “persistently attempted to reopen the substantive Court of Protection proceedings concerning [my] daughter at a time when [I] knew the Official Solicitor had been invited to act as [my] litigation friend”, I must correct the record:

No, I did not know that the Official Solicitor had been appointed.

I was never formally notified. There was no hearing, no service, no letter of instruction, and no opportunity to object or be heard. In other words, the Official Solicitor was appointed without due process, in clear breach of my procedural rights.

My legal capacity was questioned behind my back, and decisions were made about me without me. This violates not only the principles of the Mental Capacity Act, but also Article 6 of the European Convention on Human Rights, the right to a fair hearing. If the Official Solicitor was instructed on the basis that I lacked capacity without due process, that very instruction is tainted by the unlawful process that preceded it.

Yes, I have continued to pursue my appeal and just recently, have submitted three previous COP9 applications to the Court of Protection that were dismissed by Poole in February 2025, plus a new COP9 application supported by fresh evidence. That is not a sign of incapacity, it is a sign of my persistence, determination, and commitment to the truth.

I have acted throughout with the belief that the Court has a duty to correct injustices, and I have used the proper legal mechanisms to seek that correction. To treat lawful applications as evidence of incapacity is a dangerous and perverse logic, and risks punishing those who try to use the system rather than abandon it.

Reopening a case in light of new evidence is not irrational, it’s what justice demands.

In response to the section titled “Concerns about Luba Macpherson’s behaviour and conduct earlier in the proceedings,” I must challenge the underlying premise, and the way it is presented as “fact” when, in reality, none of the allegations about my “bad behaviour” were ever substantiated in law.

Over the course of seven years of Court of Protection proceedings, no proven finding of abusive conduct was made against me. Despite repeated efforts to paint me as a harmful or destabilising presence in my daughter’s life, my daughter herself has consistently and clearly denied these claims. She has told staff and social workers, and most recently and in no uncertain terms that she is upset not because of me, but because her concerns have been persistently ignored by the system. Yet the same narrative continues to be pushed, regardless of what she actually says.

It is deeply disturbing that judges have continued to rely on outdated and unproven assertions, many of which are rooted in perjury, medical negligence, and professional misconduct, all of which I have repeatedly brought to the court’s attention. I provided documented evidence of:

Despite this, Judge Moir ignored it all. Even after I confronted the court with clear procedural irregularities, including serious flaws in Dr Ince’s report and a question over jurisdiction to proceed, the court proceeded anyway, not based on fact, but on the opinion of a psychiatrist who claimed my daughter lacked capacity six months before even meeting her.

At that point, my daughter had already been assessed by another Doctor, with all legal safeguards in place, and was found to have mental capacity. But because of Dr Ince’s unverified opinion, my lawfully registered Power of Attorney was stripped, leaving my daughter unprotected and open to abuse.

And I use the word abuse deliberately, because I have clear evidence of it. It is precisely because I was trying to expose this that I became a target. The refusal to engage with this evidence, and the continued repetition of unfounded claims about my “conduct”, speaks not to my behaviour, but to the system’s determination to suppress inconvenient truths.

Strongly expressed emotion in the face of injustice is not abuse. A mother refusing to abandon her daughter is not pathology. What is pathological is a system that uses psychiatric opinion to undermine legal safeguards and silence legitimate safeguarding concerns.

In relation to Mr Justice Poole’s involvement, I must say this plainly:

What better way to silence a parent raising uncomfortable truths than to declare their mental capacity is impaired?

That’s exactly what happened in my case. The system, including judges and lawyers, simply refused to acknowledge criticism, even when backed by solid medical evidence, including assessments and expert opinions contradicting their narrative.

For years, I have tried to raise serious safeguarding concerns about my daughter. And instead of engaging with those concerns transparently, they have been met with dismissal, retaliation, and suppression.

The court repeatedly accused me of naming my daughter or filming carers, but I never once named her in public, and I have never identified any staff member in any video or post. The only time my daughter’s full name was published was by the Court of Appeal in London itself, by its own admission.

It is dangerously easy for the state to make accusations when no proof is required to back them up, and when the person being accused is treated as mentally unwell for daring to question it.

Even more shockingly, I have never been given copies of my daughter’s recent mental health assessment — the very document on which the authorities rely to declare she lacks capacity. How can such declarations be trusted when they are made in secret, without scrutiny, and against evidence to the contrary?

Transparency has been systematically denied, and so has basic procedural fairness. The state claims to protect my daughter but it has refused her voice, ignored her choices, blocked her support, and shut out those who know her best.

I believe the question of mental capacity, both hers and mine, has been weaponised to maintain control and avoid accountability. And it is this pattern of injustice that must finally be seen for what it is: an abuse of power, not a protection of rights.

The idea of the “protection imperative” is central to understanding what has happened in my case. While the term is meant to flag a potential danger, that courts or professionals might prioritise protecting someone over properly assessing capacity, in practice, I believe the “protection imperative” was not just a temptation in my case, but an operating principle.

When the Court faced the uncomfortable reality of having to send a mother to prison for speaking out about safeguarding concerns — concerns backed by evidence, it seems they reached for a convenient solution: claim that she might not have litigation capacity, and refer the question back to the Court of Protection.

This did two things:

The whole exercise created a procedural detour, not to protect me, nor my daughter, but — arguably — to protect the credibility of the system itself.

Let me be clear:

The Council and the courts have justified years of forced separation, control, and secrecy based on vague generalisations, untested psychiatric opinions, and the repetition of disproven narratives. The idea that I was “manipulating” my daughter or “distressing her with conspiracy theories” was used to justify the most extreme measures, including stripping me of power of attorney, banning contact, and jailing me for speaking out.

And yet, even Poole J himself admitted that the recordings I made and posted online caused no proven harm to my daughter:

If that’s the case, why was I punished so severely? Why was capacity suddenly questioned after six years of litigation? Why did the Court appoint the Official Solicitor without notice, and without any legal process? Why was my fight for my daughter recast as a symptom of incapacity?

The answer, I believe, lies in what Claire Martin and Dr Parvez rightly call the protection imperative, but in this case, it was not about protecting my daughter or me. It was about protecting the system, by shifting blame, avoiding scrutiny, and delaying accountability.

Real protection starts with listening. To my daughter. To me. To the evidence. That’s all I ever asked for. And that’s exactly what I was denied.

Final reflections:

Claire Martin’s blog is one of the most robust, respectful, and intellectually honest assessments of my case that I’ve seen. It treats me not as a problem to be managed, or a diagnosis to be explained away, but as a person with convictions, evidence, and a right to be heard. For once, I am not portrayed as a “difficult mother,” but as a thinker, a litigant, and a witness to systemic failure.

In this system, where the line between care and control is often blurred, and where the “protection imperative” is too easily used to silence dissent, Claire’s analysis brings clarity, compassion, and a call for deeper accountability.

I have faced an entrenched institutional machine, and I have not folded. My experience may be uncomfortable for some to confront, but it is part of a much larger reality that others are also living. This blog gives public voice to that reality, and I hope it can be a starting point for a wider conversation about power, capacity, justice, and reform in the Court of Protection.

Kind regards,

Luba Macpherson.

LikeLike