By Celia Kitzinger, 29th August 2025

Earlier this month, Sandra and Joe Preston published an account of their experience in the Court of Protection and queried whether the case about their relative’s “deprivation of liberty” was a good use of judicial time, tax-payers’ money and in the public interest. You can read their blog post here. “A court hearing and 23 visits from 16 officials: Family doubt that ‘Deprivation of liberty’ is working in the public interest”.

The person at the centre of this case (“P”) was Joe’s mother, who has dementia and lives in a care home. Sandra and Joe describe how concerns about DOLS dragged on for years, raised by successive RPPR (Relevant Person’s Paid Representatives) resulting in numerous short-term standard authorisations, before eventually resulting in a s.21A challenge in the Court of Protection in June 2025. Much to Joe and Sandra’s relief, the judge approved an Order that Joe’s mother should continue to reside at the care home where she had been living (they say) “as happily as her condition would allow for the past four and a half years. Nothing needed to change and there was nothing that could be done to make her life better”. It was a good outcome, but the process leading up to it had been gruelling: Joe and Sandra felt like “criminals” being “dragged through the court” and Joe’s mum was distressed by continual interrogations from professionals about where she would like to live. Professional concerns about “deprivation of liberty” became an intrusion into their family life for people who “certainly didn’t want our last days/weeks/months together taken up with Court of Protection and DOLS bureaucracy but instead to spend what precious time we may have left with her before the inevitable happens”. Their blog post raises important questions about why this was all considered necessary.

The implementation of statutory Deprivation of Liberty Safeguards and the way they are (or are not) working in practice is a matter of legitimate public interest. I very much admire Joe and Sandra for the civic responsibility they have demonstrated by publicly sharing their experience, in an accessible form, as a contribution to debate and critique of this area of the law. They also want to be able to reach out to other families whose loved ones are going through DOLS and offer the kind of understanding ‘listening ear’ that comes from shared experience. Publishing a blog post was a way of telling people about their experience and offering to make themselves available to support others.

But there was an obstacle preventing Joe and Sandra from achieving these laudable aims. There was a court injunction against them, preventing them from identifying themselves as family members of a “P” (protected person) in Court of Protection proceedings. The injunction meant that Joe and Sandra could have written anonymously about the case, but as soon as they used their own names, they were identifying themselves as “member[s] of the family of the subject of these proceedings”, as the order puts it – and that would have breached the injunction. Breaching court injunctions is a serious matter: on the first page of the order it says (with capitals and bold type as reproduced here): “ IMPORTANT: If any person disobeys the order … they may be found guilty of contempt of court and may be sent to prison, fined or have their assets seized”

Almost all families in the Court of Protection are bound by the same injunction: it’s the “standard transparency order” produced by default for all Court of Protection hearings and it says that nobody can publish information that identifies (or is likely to identify) the person at the centre of the case as a “P” in Court of Protection proceedings, or their family members. Sometimes the identity of other people (or even public bodies) is also protected. The transparency order in the case concerning Joe’s mother (COP 20009718) also included the manager of her care home.

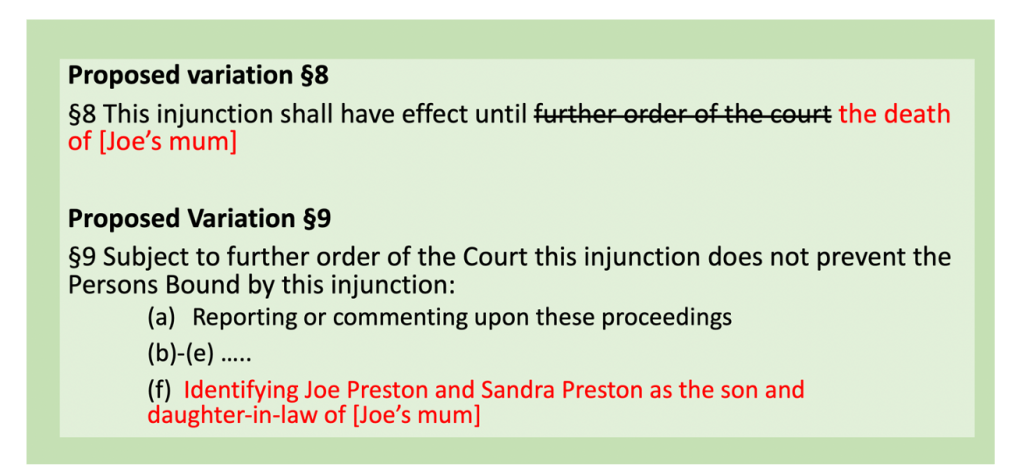

As in almost all the 400+ transparency orders I’ve seen, the order against Joe and Sandra lasted “until further order of the court”: in other words, indefinitely. They would still not be able to write or speak publicly about the Court of Protection case, even after Joe’s mother died.

So, this blog post is about how we got the injunction changed, so that Joe and Sandra could identify themselves as the son and daughter-in-law of a protected person in Court of Protection proceedings (and could do so while the protected person was still alive). I hope it’s useful to other families who also want to speak about their experience in the court.

If you’re reading this blog because YOU want to speak out about a Court of Protection case, it’s important to understand that it’s usually much more straightforward to change (“vary”) or get rid of (“discharge”) the transparency order after the protected party’s death[1]. Much of the challenge in this case was to do with the fact that the person at the centre of this case was still alive – meaning that there are (legitimate) concerns about her right to privacy.

Each case is different and needs to be considered in relation to its particular facts. These facts might include: what are P’s wishes and feelings about the application; how easy is it to identify P if family members speak out about the case, and is it likely that anyone would take the trouble to try to identify and locate P – and if they did, what is the likelihood of harm to P?; who opposes the application and why?. It’s all about balancing the benefits (of free speech) against the costs (of harm to P, including invasion of their privacy). We’ve published several other blogs about (successful) applications to vary transparency orders concerning living Ps: “A mother now free to tell her Court of Protection story” reports on Heather Walton’s (contested) application to name herself as the mother of a daughter with Down Syndrome involved in a DOLS case; and “I’m finally free to say I’m a family member of a P” reports on the protracted process endured by Amanda Hill to get the court to vary the transparency order so that she could identify herself as the daughter of a mother with dementia involved in a DOLS case. (In both cases, it was the local authority – rather than the Official Solicitor – that raised the most objections and concerns about variation to the order, and in Heather Walton’s case the local authority actively opposed the application.).

So, now I’ll describe what we did in this case that resulted in the judge agreeing to make a new transparency order which “does not prevent the persons bound by this Injunction […] identifying Joseph and Sandra Preston as the son and daughter-in-law of [P]” (§8(i)(f), order of DJ Mullins, made on 10th June 2025 and issued on 20th June 2025. The process followed here might not be right for every application – you’ll need to consider the particular facts in your own case.

How we got the reporting restrictions changed

Getting the reporting restrictions changed was very much a team effort between me, Joe and Sandra. We didn’t use a lawyer – we didn’t think we needed to (and few lawyers have experience of the complexities of varying transparency orders in the Court of Protection – I’m pretty confident I know more than they do!). I’ll report on (1) the application forms we filled in – one from Joe and then later one from me; then (2) I’ll describe what happened at the hearing; and finally (3) the oral judgment – as is the case for the vast majority of Court of Protection cases, there’s no published judgment (another reason why this blog post and so many others that we publish matter for transparency is important).

1. Application to vary the transparency order (COP 9)

With my help, Joe made a formal application to vary the transparency order, using a COP 9 form. You can download one here: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/602a3d8bd3bf7f03208c2b40/cop9-eng.pdf.

There is no charge for making an application like this.

Anyone affected by a transparency order can make an application to vary or discharge it (it says so on the standard order at §10). I make a lot of COP 9 applications every month to vary transparency orders (mostly to stop prohibitions on naming public bodies). The person making the application does not need to be a party to the case (in fact, Joe and Sandra were not parties), so long as they are “affected” by it – as Joe and Sandra clearly were: the order prevented them from speaking out in their own names about the case and interfered with their freedom of speech. (Likewise, I was affected by the order because I wanted to publish a blog post by Joe and Sandra about the case, and I would be in breach of the transparency order if I did so with their names on it.)

It’s not a particularly long or difficult form to fill in, so long as you know exactly what you are asking for and what your arguments are as to why what you want (discharge or variation of the order) is the legally right thing to do. It has two sections:

Section 1 is very easy. It asks for the details (address, phone number etc) of the person filling in the form and their solicitor’s details if relevant (you don’t need a solicitor). It also asks: “What is your role in the proceedings?” and offers four boxes to tick:

- “Applicant” (in this s.21A case, that was Joe’s mother)

- “Person to whom the application relates”

- “Other party to the proceedings”

- “Other (please give details)”

Joe ticked “Other” and then typed into the text box: “Son, Next of Kin and Lasting Power of Attorney (both) for the Applicant”. When I complete the form, I put: “Member of the public and co-director of the Open Justice Court of Protection Project, a voluntary organisation established in June 2020 to support the judicial aspiration for transparency by encouraging members of the public to observe hearings and to blog about them.”

Section 2 is harder. It has three sub-sections. The first asks: “2.1 What order or direction are you seeking from the court”. The second asks: “2.2 Please set out the grounds on which you are seeking the order or direction”. The third says “2.3 Any evidence in support of your application must be filed with the application notice” and gives some instructions. (I’ve never used 2.3 – though looking back, I think I probably should have done, since I have submitted witness evidence later; I’m grateful for the court’s tolerance of missteps by litigants in person who don’t fully understand the rules.) It’s the content of these sections that you probably need some help with – because they need you to be very specific about how you want the order changed (if that’s what you’re asking for) and/or to explain why it’s lawful to change or discharge the order now, and why in fact the court should do so on legal grounds (not just because you want them to!). I gave Joe a lot of help with filling in this form (and am happy to help others – just email the Project).

The form is badly designed. There are character limits for the text boxes but it doesn’t say what those character limits are: if you type too much in the boxes on the screen, then even if you can see all the words in your version of the document, it’s quite likely the text will turn out to have been cut off and be invisible to the recipient. For that reason, Joe just put a couple of sentences in the text boxes and then attached some pages of text.

For 2.1 (What order or direction are you seeking from the court?), Joe wrote:

“Variation of the Transparency Order (TO) made and issued by DJ Ellington on 16 January 2025, in the standard terms. The variation will (i) permit identification of myself and my wife as family members of [P]; and (ii) cause the injunction to cease to have effect upon [P’s] death. Proposed wording is attached.”

It’s important to be very clear and factual and to specifically identify the order you are seeking to have changed – especially as in any COP proceedings there may have been more than one TO across the course of the hearings (and – as here – the TO was not necessarily made by the judge who is now hearing the case). It’s also important to say what exactly you want changed and how. If you can offer some proposed wording (which can be challenging since we’re not trained to write legal documents), it can help the court. I helped Joe with the wording by drawing on the wording in other TOs that had already been varied to permit other family members to speak out.

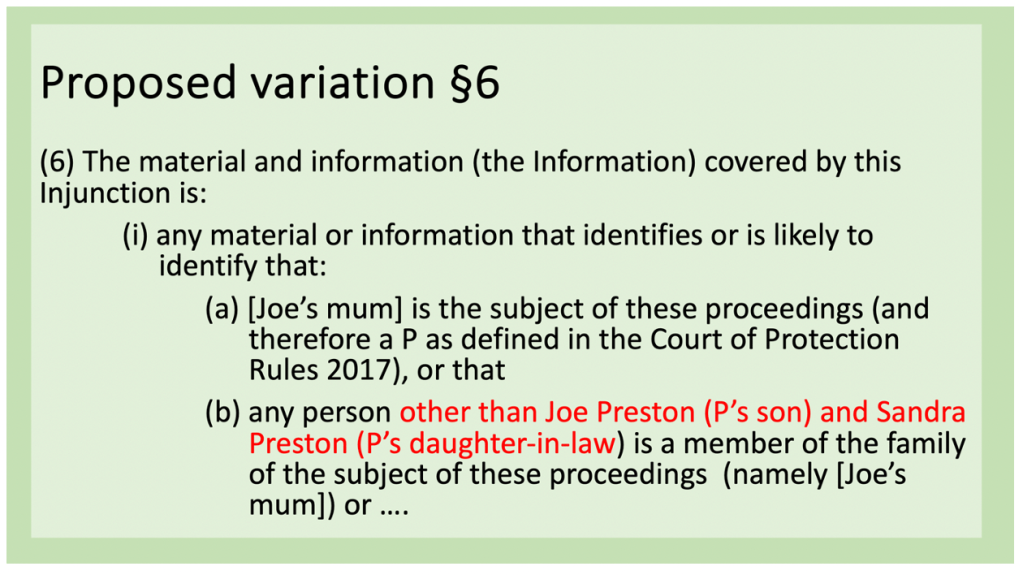

In the attached document, Joe further specified that “The intended effect of varying §6 is to permit identification of myself and my wife as [P’s] son and daughter-in-law. It is not intended to permit identification of P (e.g. by name), or where she lives or is cared for, nor is it intended to permit identification of professionals involved in this case”. He then set out the proposed variations. I’ve illustrated them here by reproducing the original text of the order and adding in red the changes Joe was asking for. (If you have your own transparency order, you might want to look at it now and see how it would need to be amended to achieve the effect YOU would like to happen.)

In response to 2.2 (“Please set out the grounds on which you are seeking the order or direction” Joe wrote: “In the particular circumstances of this case, variation of the Transparency Order in the proposed terms strikes the right balance of my own and my wife’s ECHR Article 10 right to freedom of speech (and the public’s Article 10 right to freedom of information) with [my mother’s] ECHR Article 8 privacy rights. See attached.”

The ”attached” document explaining Joe’s grounds was five pages long. It began by saying that the current order was “an unjustified restriction on our freedom of expression”. He explained that he and his wife wanted to “talk and write about our experience as a family, in particular as regards the effects of the Mental Capacity Act 2005 on our lives… and our experience of court proceedings…”. He said that they wanted to be free to “openly share information about the COP case with friends and family, and with other people involved in DOLS and COP, for example through the Open Justice Court of Protection Project”, and that they wanted to do that in their own names, since this would have greater impact than an anonymous text.

Joe said that unlike other cases where the protected party has been named (I gave him a list of examples of such cases including William Verden, Robert Bourn, Michelle Davies, Laura Wareham, Manuela Sykes, and if you google their names you can learn about them), he was NOT making an application to name the protected person (his mother) – or anyone else in the family. If you are not actually applying to name P say so explicitly, because (especially if P is still alive) it will make your application less controversial. Joe acknowledged it it was possible that people would be able to figure out her name from knowing that she’s Joe’s mother – but also thought it very unlikely that anyone would bother (why would they?). He wrote movingly about what his mother’s likely views would have been:

“We know that, when she had capacity, [my mother] would have wanted us to be able to publish information about her legal case. She would trust us to be sensitive and respectful of her privacy in doing so. She has been caught up in a legal situation she could not have imagined in advance and would want us to be able to talk to other people about that, so that they can better prepare themselves for this sort of situation. She would want her friends and family to know the broad outline of what is happening in her life. She would be proud of me for wanting to use my experience to help other people, having instilled in me since an early age, values such as honesty, integrity, respect, kindness, and considering others. She would not want me to shy away from an opportunity to support and assist others and she would consider it the coward’s way out to simply move on without looking back and sharing lessons about what went well, or less well, in order to do better next time. If she knew that I had turned down an opportunity to help others, she would be unable to conceal her disappointment in me, and were she not quite so frail, she would probably threaten me with a clip round the ear.”

Finally, Joe also mentioned his reasons for wanting the duration of the order changed from “until further order of the court” to “until the death” of his mother. This change, he said, would “obviate the need for another COP 9 application to discharge the TO on the death of [my mother], which would be distressing for me after my mother’s death, and also take up court time unnecessarily”. He also pointed to a recent Supreme Court case (Abbasi) which – as I’d explained – is widely understood as making blanket reporting restrictions for indefinite periods (like “until further order of the court”) entirely untenable (see “Reflections on the Supreme Court’s judgment in Abbasi on the duration of reporting restrictions”).

Joe submitted the COP 9 form and we waited to see what would happen next. There was already a date listed for a final hearing concerning the substantive issues in the case (the s.21A matter) before District Judge Mullins sitting at First Avenue House in London on 10th June 2025. Sandra reminded me (when I sent her an earlier version of this blog post) that “the local authority and the Official Solicitor tried to get us to delay putting in the COP 9 until after the s21A proceedings had finished” – which would have left the injunction hanging over their heads until another hearing could be arranged. We hoped we could get the judge to squeeze it in at the last moment while there was a hearing still listed (and which would otherwise have been vacated since the parties had now reached agreement, and the judge would be given a draft approved order agreed by everyone, including Joe and Sandra). Lots of hearings are vacated and if a judge actually has a slot available due to a vacated hearing, my view is always ask them to use it! Doing that definitely paid dividends. The judge did look at the draft approved order and made some changes that Joe and Sandra thought were helpful. And he did deal with the issue of the transparency order (which is what took up most of the hearing).

On learning from Joe and Sandra shortly before the hearing that there were some concerns from the local authority about the application to vary the transparency order, I also submitted an application of my own (very last minute!) asking to be joined as an applicant (or as an intervenor, or simply given permission to speak to the court) due to my experience with the Open Justice Court of Protection Project which has led to many applications for varying and discharging transparency orders.

DJ Mullins directed that both Joe’s application and mine (with me joined as an applicant) should be heard on the hearing on 10th June 2025.

2. The hearing

The first part of the hearing dealt with the s.21A deprivation of liberty issue for Joe’s mum. Everyone agreed that she was now settled and happy in the care home and there was no need to consider alternative placement options. She’s shown “no signs by word or action of objection to [the care home] since April 2024” and she has informed her solicitors that she “loves” the staff and “likes” the care home. The local authority apologised for the delays in bringing the application to court. The standard authorisation was extended for another six months, and it was agreed that it was fine for Joe to act as his mother’s RPR. This was all good news for Joe and Sandra (and for Joe’s mother).

Then the judge turned to the transparency order.

Joe talked about how much he cared for his mother and said he wouldn’t have made this application if he thought it would cause harm to her. But the whole DOLS process had been “stressful and upsetting” to him and to his wife. They feared they had already inadvertently breached the TO (e.g. by writing to their MP about the case) and they wanted now to “remove some of the fear from what has been an overwhelming process” by being free to talk to others about what has gone on. Plus “Mum would be pleased that these challenges might create the opportunity for us to support others”. Sandra added: “it would turn a negative into a positive”.

Poignantly, Sandra also gave a very moving example of the effect of the TO on her life that very day. “I’m here today”, she said, “on the anniversary of my Dad’s passing, I had to tell my mum something about why I couldn’t be with her today – but I couldn’t say much without breaching the transparency order”. She became tearful, adding: “I don’t want to be bound by these issues that tie us in knots when we’re seeking to help others”.

I don’t remember what I said: I couldn’t speak and make notes at the same time. But I have a position statement which covers the basics, including:

- the need for an “intense focus” on competing Article 8 (right to privacy) and Article 10 (right to freedom of information) as set out in Re S by Lord Steyn

- the clear and legitimate public interest factors in this case, given an ageing population and increasing numbers of families facing the challenges of caring for elderly parents with dementia

- the lack of evidence of any harm to Joe’s mother, given that the parties acknowledge that Joe clearly has his mother’s best interests at heart

- the evidence that Joe’s mother trusted him and Sandra to act in her best interests (she appointed them both with Lasting Powers of Attorney)

- the evidence that she would want Joe and Sandra to be able to speak publicly about what has happened

- the risk to public perceptions of the justice system if family members’ freedom of speech is curtailed without compelling and robust reasons as to why it is necessary and proportionate so to do.

In the event, neither the Official Solicitor nor the local authority opposed our applications to vary the Transparency Order. The local authority raised various caveats – including

- concerns about “editorial guidelines and/or standards” of the Open Justice Court of Protection blog (For anyone facing that objection in future, it may be useful to quote Lieven J: “it is of the greatest importance to understand that it is not for the Court to consider the quality or fairness of the reporting. The Court is not an arbiter of the editorial content of reporting” Tickle v Father & Ors, [2023] EWHC 2446 (Fam))

- a suggestion that the court “may find the justification that the amendment is necessary because writing under one’s own name rather than a pseudonym ‘has greater impact’ to be relatively weak”. Tell that to Lord Rodger in Guardian News and Media Ltd and Ors [2010] UKSC 1: “’What’s in a name?’ ‘A lot’, the press would answer. This is because stories about particular individuals are simply much more attractive to readers than stories about unidentified people. It is just human nature”

The local authority also resisted the suggestion that the (revised) transparency order should expire automatically on the death of Joe’s mother, proposing instead that the order should extend for an additional three months. The justification for this seemed to be to protect Joe and Sandra on the grounds that their position “may change” when she dies, because “loved ones passing is a very difficult time”. It seemed unclear to the judge (and to me) what the local authority envisaged might happen on P’s death that could be averted by this variation. At most, he said, “there might be a simple and dignified statement” added to the blog posts, naming her and recognising her death.

3. Judgment

The judge thanked all the parties for their submissions and (very graciously) added that he was “grateful to Professor Kitzinger for bringing her experience of transparency and transparency orders and practice into this case and making an application of her own and for her position statement and oral submissions”.

He said he would make a short judgment. After acknowledging the competing rights at play, he said he would allow the application to vary the order in the terms requested – although he would achieve this by discharging the current transparency order and making a new one.

The judge said that in coming to his decision he had taken into account the relevant legal framework and the facts of this case. He highlighted the motivations behind the application that weighed heavily with him in lifting the restriction on naming Joe and Sandra.

“Mr and Mrs Preston have emphasised that the story they want to tell is their story – about the stresses and strains of being part of this process and having a loved one who is going through this journey through dementia. They want to share their experience with the aim of helping and supporting others – and I think – and it’s a legitimate reason – helping themselves by discharging an obligation [Joe’s mother] would have wanted them to discharge. The change to the transparency order will also allow others to identify them and comment on their role in the case. They are aware of that, and Professor Kitzinger’s presence here today, representing the Open Justice Project she pioneered, embodies that fact – although this is not of course the only organisation or set of people that might want to write about this case, and not everything written about Mr and Mrs Preston will be what they would have wanted. But what this reminds us of is how important this court’s presence is, and the importance of getting out into the open people’s experience of the process of coming to court and what works well and doesn’t work well.”

The judge acknowledged that there was a risk that Joe’s mother would be identified by virtue of Joe and Sandra’s names becoming public, and that there could be an effect on her own privacy – “and in a different way a consideration that even though she’s not named, if Mr and Mrs Preston are named and wider public domain debate – even to the modest extent anticipated – takes place, then her circumstances will move more into the public domain than she might have wanted.”. Having said that, he acknowledged facts which militated against too much negative impact: she has a different surname from Joe and Sandra, and Joe is “absolutely clear his mother would have wanted to have him make use of her situation to help others even if that involve some degree of invasion of her privacy”. His conclusion was that during her life-time the balance was clearly in favour of the revisions suggested.

The judge also decided “on the facts of this particular case”, in favour of an order that ends on Joe’s mother’s death – i.e. without need for a further court application to discharge it. That’s because he “accepted that [Joe’s mother] would have wanted to help other people and I sought to identify what interest of hers would be protected in that 3-month period proposed by the local authority and I struggle to see what the interest would be”.

Aftermath: what’s changed now that the transparency order is discharged?

In the three months since DJ Mullins changed the transparency order for Joe and Sandra Preston they have written two blog posts. One deals with what went wrong in their family experience with DOLS: “A court hearing and 23 visits from 16 officials: Family doubt that ‘Deprivation of liberty’ is working in the public interest”. Their blog post has been influential in prompting discussion and debate about the role of the Relevant Persons Paid Representative and we making plans to develop this. Sandra has also taken the step of attending hearings at First Avenue House as an observer – and she’s written a blog post about that: My first experience of being an in-person observer at First Avenue House (London): HHJ Beckley decides on where P should live and receive care

Discharge of the transparency order has felt like a burden lifted in their personal life with family and friends. Joe says: ” The relief of being able to update friends and family who care about Mum has been immense. Mum’s oldest friend, who used to phone her every week and stopped only when she could no longer make sense of their conversations, called this week to ask how she was and to see how we had got on at court, and it was such a relief to be able to tell her about the court’s decision.“

Because they are able to be open about their family experience of caring for an elderly parent with dementia – including their experience of DOLS and the COP – others with similar experiences feel more able to turn to them for support and understanding. Joe says: “A couple of weeks ago we were asked for advice by a friend of ours whose mother has been displaying challenging behaviour due to her vascular dementia; she said that knowing a little of what we had been through made her feel more able to talk openly with us. Another friend who is caring for his elderly mother and facing challenges over deputyship also admitted he felt more able to confide because he knew that we had faced issues with court processes”. As I read this I was reminded that Joe and Sandra had raised in court their desire to help others in similar situations and that I was struck at the time- and am still more forcibly struck now – by the dismissive response of the local authority. The local authority said that, although educating others and sharing experiences is “a legitimate and justifiable aim under Article 10“, this argument is “… tempered by the fact that those involved in Court of Protection proceedings have the right to apply to become parties to that litigation and/or to seek expert legal advice should they choose. Mr and Mrs Preston will be providing … anecdotal accounts of their interaction with the public bodies and the courts, and are not in a position to offer any legal advice”. And that, I think, rather spectacularly misses the point! It’s precisely the “anecdotal account” – the experiential story – of Joe and Sandra’s interaction with the public bodies and the courts that strikes a chord with others, brings the law to life, and helps everyone to better understand the effects of law and social policy on our everyday lives. A big thank you from me to Joe and Sandra for their willingness to do this after a gruelling and distressing few years. It takes courage and commitment to (as Sandra put it) “turn a negative into a positive” by reaching out to help others.

Finally, although the court case is over, the challenges Joe and Sandra face are not. I’ll leave the last word to Joe: “We may have been able to close the door on the court case, but we cannot hide from the fact that Mum’s illness is still there and provides us with daily challenges. That feeling of dread whenever the phone rings and we see that it’s the care home is one that we can’t avoid – but knowing that we can no longer be found to be in contempt of court is one weight lifted off our shoulders.”

Celia Kitzinger is co-director of the Open Justice Court of Protection Project. She has observed more than 600 hearings since May 2020 and written more than 100 blog posts. She is on LinkedIn (here), and also on X (@KitzingerCelia) and Bluesky @kitzingercelia.bsky.social)

Footnote

[1] Discharging a transparency order, even after the death of the protected party, can also pose difficulties too – especially if family members disagree between themselves about whether or not people’s names should be in the public domain. This is probably more likely when the Court of Protection case has also involved disputes or disagreements between family members See “When families want to tell their story”. Public bodies – local authorities, ICBs, Trusts – can also oppose discharge of a transparency order even after a person’s death as here: “Silence from HHJ Rowland” – and as that blog post illustrates only too clearly, the legal processes can be impossibly complex and unhelpful.

Congratulations! Very well done indeed,Annette LawsonSent from my iPad

LikeLike