By ‘Anna’, 30 April 2024

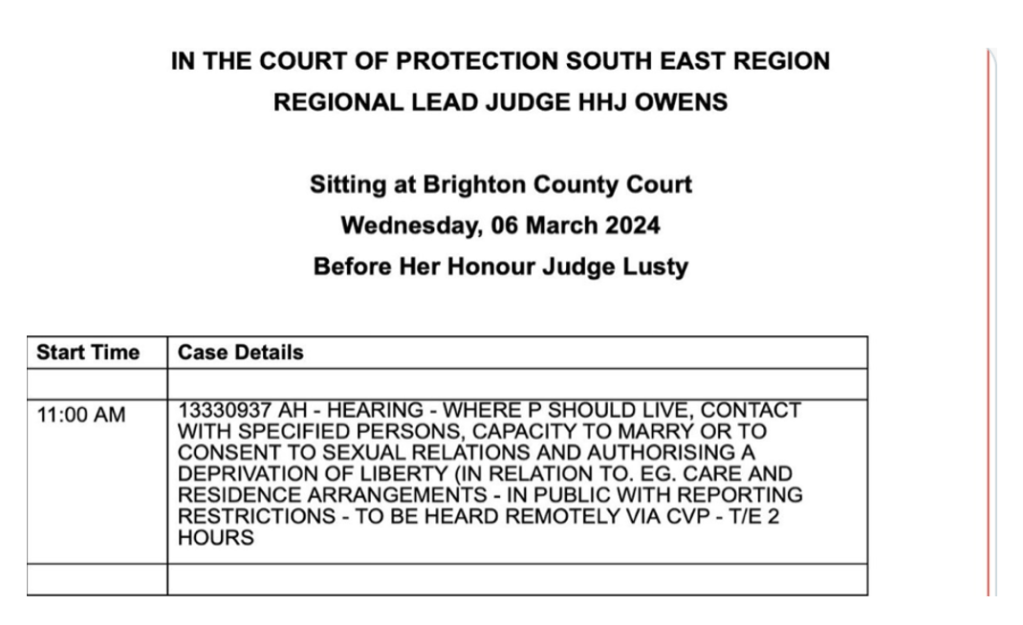

I want to learn more about capacity, how capacity assessments are done and how Court of Protection judges determine whether somebody has capacity to make decisions. So, when I saw the following hearing listed on the Open Justice Court of Protection Project Twitter (X) page, it sounded an interesting hearing to observe as the case involved various different decisions about capacity:

Although the hearing was listed for 2 hours, it actually only lasted for about 30 minutes.

Having read the position statements from both the local authority, East Sussex County Council, (the applicant) and the Official Solicitor (OS) (representing P, the first respondent) before the hearing, I knew that a lot of work had gone on behind the scenes to ensure that the parties were in agreement about a way forward. But even though the hearing was short, I learned a lot from it, including the role of expert witnesses and about the process of capacity assessments. I was able to do this not only from observing the hearing but from receiving the position statements (PS) in advance so I thank the parties’ representatives for allowing me to have them.

The PS from the OS was particularly useful because it was 22 pages long and included a lot of detail about the law relating to capacity. It also included an annex at the end which detailed a summary of the expert witness’s conclusions and reasoning of the various capacity assessments she was being asked to make, over a number of different areas. I will start by setting out the background to the hearing, before describing the hearing itself and then reflecting on what I have learned from it, including about the role of expert witnesses, the role of family and how I experienced open justice.

Background

P, the protected party in this case, is a young woman with complex needs arising from a brain injury acquired when she was 7 years old. She lives with her mother and siblings. P currently has a boyfriend (T) who is under the age of 18, T. P wishes to be in a relationship with T, and engage in sexual relations with him. It is also reported that she wishes to have children. She doesn’t agree with some of the restrictions in place, including those which affect her freedom and ability to spend time with T, unsupervised. She does not disagree with all of the support in place for her, though, and she wants to remain living in the family home with her mother.

The LA first applied to the court in January 2023, wanting declarations regarding P’s capacity to make decisions in various domains. They also applied for an ‘authorisation of deprivation of liberty in her best interests’. Since that time there have been various case management orders made through previous hearings, round table meetings and discussions with the parties, interested persons[1] and the joint expert, Dr Lilley[2], who had been appointed to conduct the capacity assessments.

The case had now reached a hearing on 6th March 2024, 14 months after the initial application. The PS for the OS outlined the issues before the court, which were whether P has capacity to make decisions about:

a) her residence

b) her care

c) contact with close family members

d) her contact with others (excluding close family members)

e) contact with a person with whom she may wish to engage in sexual relations

f) decisions about the support she requires when having contact with a person with whom she may wish to engage in sexual relations

g) engaging in sexual relations

h) her use of the internet and social media

and about her capacity to:

i) conduct the legal proceedings

The court was also being asked to determine best interests for P in relation to her care arrangements and whether the restrictions that amount to a deprivation of liberty are necessary and proportionate to the risk and likelihood of harm for P. The final issues for the court were what evidence and plans were required to determine P’s best interests in relation to arrangements for contact with T, arrangements for contact with other persons with whom P may wish to engage in sexual relations[3] and finally P’s use of the internet and social media.

I reflected on reading this that 14 months is a long time in a young adult’s life, especially one who wanted to spend time with a boyfriend, and that there were a lot of issues before the court. One sentence in the PS for the LA particularly struck me: “it is not in P’s best interests for the proceedings to drag on indefinitely nor for them to be a vehicle to micro-manage all aspects of P’s welfare.”

Assessment of P’s capacity to make decisions in the various domains was conducted by Dr Lilley, who wrote four reports. According to the local authority, “her opinions on capacity remained consistent apart from in one area: consent to sexual relations.” It seems as though there had been a lot of debate around this specific domain, and in particular around a difference between P’s capacity to engage in sexual relations with T, and engage in sexual relations with non-specific others. Dr Lilley’s initial conclusions were that P lacked capacity to engage in sexual relations, then that she lacked capacity to engage in sexual relations for anyone other than a person such as her boyfriend T. A meeting was held in late January 2024 between Dr Lilley and all the interested parties. Following that, Dr Lilley wrote a fourth and final report, with that recent view being that P does have capacity to engage in sexual relations. As all parties are now in agreement, it was deemed that it was not necessary for Dr Lilley to attend the hearing.

The agreed position between the parties now being put forward to the court was that P lacks capacity to conduct the proceedings, make decisions about her care, make decisions about her contact with others, except for contact with close family members she knows well, and to make decisions about using the internet and social media.

She does, however, have capacity to engage in sexual relations and make decisions about her residence.

The reason for the hearing was that the court was being asked to make final declarations as to these assessments of capacity and the best interests decisions on behalf of P outlined above.

The hearing on 6th March 2024[4]

The hearing started at 11.20 am and finished at 11.50 am. Judge Lusty was in a physical courtroom but everybody else was appearing remotely. On logging on, I had added the label “public observer” to my name and I was glad I did because on joining the hearing Judge Lusty asked Lindsay Johnson, Counsel for the LA, to introduce everybody. Judge Lusty also asked me to confirm that I had received, read and understood the TO and I confirmed that I had.

The other people in court included Counsel for the OS Gemma Daly, solicitors for both the OS and the LA, P’s case manager at the care provider, a privately instructed Clinical Psychologist, a member of the social work team and a representative of P’s Property and Affairs deputy. It struck me that everybody attending the hearing was a professional involved in the case. P was not present and neither were the other two respondents to the case, nor any other friend or family member.

There was no summary of the case (so it wasn’t best practice in accordance with guidance from the former Vice-President of the Court of Protection, Mr Justice Hayden). But as I had received the parties’ position statements in advance it was probably thought unnecessary, which – as I believe I was the only observer – it would have been.

Counsel for the applicant local authority

Lindsay Johnson set out the latest developments. He started by saying that Dr Lilley had updated her report following the very useful meeting on the 31st January. It had clarified views and there was now an agreed position as to P’s capacity across a number of domains, which were included in the draft order (and as I have set out above). He stated that her capacity to make decisions with regards to residence was that she could choose between two different options but that was not an imminent issue. He was asking the judge to make final declarations, to build on interim court orders. But there had been a major change in Dr Lilley’s views on P’s capacity to engage in sexual relations, from the original view of no capacity, to a modified view of capacity to engage in sexual relations with T, to now being assessed as having relations to engage in sexual relations. This meant that capacity issues had been agreed.

Best interests decisions now needed to be made, but at present the judge did not have all the evidence before her. A draft plan of contact was in the order, including plans for unsupervised contact between P and T, where there was general agreement. There would be a return to the court if more restrictive measures were proposed. In essence what remained to be determined was a plan for P to have contact with other people, the so called TZ N°2 plan. The social worker was going to prepare that, which would then be agreed with the OS.

The best interests of P with regards to use of the internet and social media was also outstanding. Mirroring software that allowed for proportionate monitoring of social media was the restriction currently in place. It was proposed that the draft care plan should include everything with regards to best interests before the court, namely the TZ N°2 plan and methods for monitoring social media and internet use.

Lindsay Johnson also raised the fact that P’s mother should be given an opportunity to provide a statement to the court if she wished to. She had not taken an active role in proceedings to date and had not chosen to file evidence. He said that he wanted her to have a voice in the proceedings, although he was in no way suggesting that she didn’t want to be involved in P’s care. He proposed a round table meeting and /or an advocates meeting.

At the final hearing, the arrangements for care, via the care plan, will be presented. The judge will have to decide if the proposed plans posed proportionate restrictions to P’s liberty.

Counsel for P (via her litigation friend the Official Solicitor)

Gemma Daly stated that the OS accepted the conclusions of the order. With regards to capacity, the judge could make s.15 final declarations on the matters in the order. The concerns about Dr Lilley’s evidence had now been resolved now that she had changed her position. The connected concern about contact with others had also been resolved. Contact with close family was now a separate issue and it was deemed that P does have capacity in that domain, as a distinction to “contact with others”. Dr Lilley’s view was that P could gain capacity when she gets to know somebody over time. The difficulty in this case was the distinction between capacity to engage in sexual relations with somebody (which she was deemed to have) but the fact that she lacks capacity to make decisions about contact with others.

Gemma Daly referred to a paragraph in Dr Lilley’s most recent report which reads. “I now consider that P does have capacity to make decisions about sexual relations with others generally, not just with T. She does understand and retain the relevant information and she is capable of using and weighing it and communicating to make decisions about engaging in sexual relations”. With regards to contact with others, “P lacks capacity to make decisions about contact with others, with the exception of close family members she knows well and has known for many years. This should be subject to review”.

Gemma Daly stated that logically there was a distinction between capacity to engage in sexual relations and capacity to make decisions about contact with others in this case. She went on to say that there was not a longitudinal approach to capacity in this case and the judge was not being asked to make an order as to this as it would be contentious. She went on to outline that the “causative nexus”, the cause of the lack of capacity, was a mental disorder and was not due to P’s age or maturity. However, because of her age and maturity, her capacity would have to be kept under review.

In terms of capacity for decisions as to the use of the internet and social media, Dr Lilley had not had the opportunity to assess whether she has capacity. (The report states that she lacks capacity but that “this should be subject to review, particularly as restrictions are reduced and more information about her current functioning becomes available.” P had not been able to hold information in mind because of her impulsive behaviour. Education has helped, but she still lacks capacity. The order asks for review periods to be added to the care plans.

In terms of best interests, Gemma Daly referred to §33 of her PS, stating that P’s capacity to “engage in sexual relations with others would be restricted somewhat by best interests regarding her contact and the support she requires”. She referenced Mr Justice Hayden’s comment in Manchester CC v LC & KR [2018] EWCOP 30 that “It has been canvassed that if the court is to restrict LC either in part or, potentially, fully in such a sphere (i.e. where she has capacity) the court ought to only consider such measures under the parens patriae jurisdiction of the High Court.” (I understood by this that if P wanted to engage in sexual relations with somebody other than T but was restricted because she was not deemed to have capacity to have contact with them and a judge would have to decide whether it was in her best interests for contact, then that would have to be heard in the High Court. At present it isn’t a situation that has arisen.)

Summing up

The judge then summed up. She said that things have moved on since they were all together and she didn’t underestimate the effort that had been put in, especially by Dr Lilley. She was satisfied that she could make s.15 final declarations in the draft order which had been read by Mr Johnson. She appreciated that Dr Lilley’s views had changed but the evidence had made it clear why they had changed. She was not in a position to approve a final order because it was necessary to continue interim restrictions. However, there were sensible directions to hopefully take the case to the point of concluding, to the benefit of everybody. The final hearing is listed for 2pm – 4pm 28th May 2024.

The judge finished by asking that her thanks be sent to Dr Lilley and by saying that “everyone’s approach has been conciliatory which has been very helpful”.

Reflections

This hearing underscores the importance of an expert witness to decisions about capacity. Clearly a lot of work had gone on behind the scenes and I thought it was interesting to hear about a case where an expert witness had changed their opinion, and to be given an insight into the process that led to that. This hearing underlines that people can have (or lack) capacity for different things and at different times and that there is no such blanket term as ‘having capacity’, which I think lay people like myself can sometimes assume.

As a family member involved in a COP case myself, and keen to be involved, I wondered why neither P nor any family member was at the hearing. I was pleased to note that Lyndsey Johnson was keen for the family’s voice to be heard. This case highlights that, sadly, anybody at any time can become a P in a COP case through an unexpected injury, and any family can find themselves involved too. That’s why open justice is so important in increasing understanding and awareness of the Court of Protection.

Finally, the process of gaining access to be able to observe the hearing was an exemplary instance of open justice. I sent a standard email to the court, requesting the video link, the transparency order (TO) and the position statements (PS) at 7am the morning of the 6th March. I received the TO at 7.35am, from the administration officer of the SE court hub. I then received the link to the hearing from the clerk to HHJ Lusty at 8.30am. I was then surprised to receive another email from the administration officer at about 9.50am, saying that Judge Lusty had informed her that “Counsel for the OS is just waiting for instructions from her solicitors about the disclosure of their position statement”. And then at 10.10 am I received both PSs, a full 50 minutes before the hearing was due to start, giving me a good amount of time to read them. This was the first time I could recall being sent the PSs before the hearing. I have sometimes been sent them when I have requested them again after a hearing but I would say that more often than not I am not sent them.

So, in this case I was able to really appreciate what was covered in the hearing. The PS was redacted so that P could not be identified, nor the other two parties. This was in line with the TO. It was so useful to me to have read both of these before the hearing started.

‘Anna’ is the pseudonym of a woman whose mother was a P in a Court of Protection s.21A (challenge to a Deprivation of Liberty) application. She is a core team member of the Open Justice Court of Protection Project. She is particularly interested in family experiences of the Court of Protection and increasing understanding of the Court of Protection for families. Anna is not using her real name because she is subject to a transparency order from her mother’s case. She is hoping to change this. She has written about her family’s experience: ‘Deprived of her liberty’: My experience of the court procedure for my mum

[1] These included P’s Property and Affairs deputy, her case manager, and a psychologist, who were all present at the hearing I observed. A social worker was also present.

[2] I have been unable to identify who exactly Dr Lilley is, as she was not named in full in either the court documents or during the hearing

[3] This was identified in the LA PS as a TZ-style plan, after TZ (N°2) [2014] EWHC 973. Daniel Clarke has blogged recently about another case involving a TZ-style plan here

[4] It is forbidden to record any part of a hearing and I don’t touch type so my notes will not be 100% accurate.

These proceedings and hearings are always fascinating and sad in equal measure but incredibly difficult to resolve. It’s good to hear the expert witness had changed their opinion and outlined the reasons for it which to be honest, more should do. The more information and assessment that takes place, the more likely it is that changes and new information becomes relevant so it should lead to a full reassessment rather than someone sticking with what they originally determined.

I’m curious to know about T and what his situation is? 🤔 Be interesting to follow this one.

LikeLike