By Clare Fuller, 4th January 2021

Uncomfortable questions were raised for me when I witnessed the hearing (COP 13861502 Re MW) on 13th December 2021 before Sir Andrew McFarlane, President of the Family Division (also blogged here: “Patient dies in hospital as Trust fails to comply with Mental Capacity Act 2005”).

When I joined the hearing, I was unaware that the lady at the centre, Mrs W, had sadly died the previous evening.

Learning this, in the opening minutes of the hearing, added an emotive element and changed the hearing from a decision-making process about Mrs W’s future to a more unusual “lessons to be learned” situation.

It was, as counsel said “a profoundly sad time” for the family, who had also experienced the death of their father just twelve days earlier.

As the case opened, we learned that the Trust (the London North West University Healthcare NHS Trust) had commenced a full Serious Untoward Incident (SUI) investigation and would be referring Mrs W’s death to the coroner.

The Court heard from Mr Hallin (who represented Mrs W via the Official Solicitor) that “it is hard to accept there may not be other cases which have not come before the Court” and listening to the case I agreed.

The case was originally brought to court by the family of Mrs W when they were told that clinicians had withdrawn Mrs W’s nasogastric tube. The nasogastric tube ensured that Mrs W received nutrition and hydration, and had been in place since around 23rd November 2021. After it was withdrawn, her hydration was provided by an IV route, but she received no nutrition other than some sugars dissolved in her hydration.

Details of the case as disclosed in earlier hearing on 10th December 2021 can be found here and (in a report on this same hearing) in this blog post.

Why this case interested me

I promote proactive Advance Care Planning, conversations about What Matters Most and formalising planning through tools such as Lasting Power of Attorney.

I advise people that appointing an Attorney, via a Lasting Power of Attorney, is part of normal life planning. I do so in the belief that this provides a legal framework ensuring that decisions about whether or not to consent to treatments can be made by people we choose if our capacity to make independent decisions is lost.

The hearing demonstrated that, without professional understanding and good organisational practice, frameworks for planning ahead can fail.

There are two specific legal frameworks at the heart of this blog, each of which I’ll address in turn. They are (1) Lasting Power of Attorney; and (2) Do Not Attempt Cardio-Pulmonary Resuscitation (DNACPR) decision-making.

1. Lasting Power of Attorney

A Lasting Power of Attorney is a legal document that enables a someone to nominate a person or persons to act for them if they ever lose capacity to make decisions for themselves.

There are two Lasting Power of Attorney forms, one for Health and Welfare and one for Property and Finance.

In a previous blog, I have focused on Property and Finance decision-making; here the issue is Health and Welfare. However, the basic principles that professionals need to understand are the same for both.

Mrs W had nominated one of her sons and one of her daughters as attorneys for a Health and Welfare Lasting Power of Attorney. She selected Option A in the Lasting Power of Attorney application. This meant that Mrs W gave her son and daughter authority to give or refuse consent to life sustaining treatment.

Provision of nutrition via a nasogastric tube is a life sustaining treatment and included as an example in the formal guidelines for making a Lasting Power of Attorney:

By not consulting with Mrs W’s attorneys the Trust failed to recognise their legal role.

The lack of communication has been highlighted as a failing for which the Trust has apologised.

The law is clear on withdrawal of clinically assisted nutrition or hydration (CANH) following the Supreme Court case of An NHS Trust v Y and another [2018] UKSC 46 and the subsequent publication of national Guidelinesby the British Medical Association and the Royal College of Physicians, endorsed by the General Medical Counsel.

GMC guidance (since 2010) has been clear that doctors must seek a second medical opinion where a decision is made not to start, or to withdraw, CANH in a patient who is ‘not expected to die within hours or days’ (as in this case). The guidance is reiterated in Re Y and in the national guidelines.

Celia Kitzinger and Jenny Kitzinger comment on the “apparent disregard for the fact that the patient has a son and daughter who she designated as her health and welfare attorneys. She assigned them authority over consenting or refusing consent to life-sustaining decisions, and backed this up with a statement of preferences (or instruction) on the form appointing them.clinicians – If life-sustaining treatments were on offer, then the decision-makers were the son and daughter, NOT the clinicians – and it was up to them to make the decision as to whether it was in her best interests to continue with CANH or not.

Guidance published by the BMA in 2018 for clinically assisted nutrition and hydration (CANH) and adults who lack the capacity to consent clarifies the role and importance of a Health and Welfare attorney: “Legally, family members cannot give consent to, or refuse treatment on the patient’s behalf unless they have been formally appointed as a health and welfare attorney“.

The decision-making process is summarised in a useful flowchart in the guidance. The flowchart demonstrates explicitly the hierarchy of decision making in a person who lacks capacity. Taking precedence is an Advance Decision to Refuse Treatment (ADRT), followed by a Health and Welfare attorney with relevant power.

I find this flowchart invaluable in demonstrating the importance of Advance Care Planning, and a stark reminder that without an ADRT or Power of Attorney a family member does not have authority to consent to or refuse treatment for their loved one. One positive action that might result from this case and associated publicity is greater awareness of Lasting Power of Attorney and ADRT.

Witnessing the hearing it appeared that the failing to consult with attorneys was not the action of a single person, rather a systematic failure.

This made me question the professional understanding of Lasting Power of Attorney within the Trust.

As a Registered Nurse, I have completed mandatory Mental Capacity Act (MCA) Training since the Mental Capacity Act was introduced in 2005. I have worked in a number of different NHS organisations and Trusts and draw on experiences from them all. Training invariably included awareness of Lasting Power of Attorney, but specific detail was absent. My learning and understanding of Lasting Power of Attorney has been gained through professional curiosity and my role as a Lasting Power of Attorney Consultant

With an awareness of the general lack of professional understanding about Lasting Power of Attorneys I have previously blogged about how to check the validity of an Lasting Power of Attorney here and in further detail here .

The key points I summarised for clinicians checking a Lasting Power of Attorney:

- Clarify which Lasting Power of Attorney has been made – Health and Welfare, Property and Finance or both.

- Be aware that you need to know more than if someone “is” an attorney; for Health and Welfare LPAs you need to understand the detail of the LPA, specifically if option A or B has been selected for life sustaining treatment, and any instructions the donor has given to the attorneys, or wishes and preferences they have expressed, on the form.

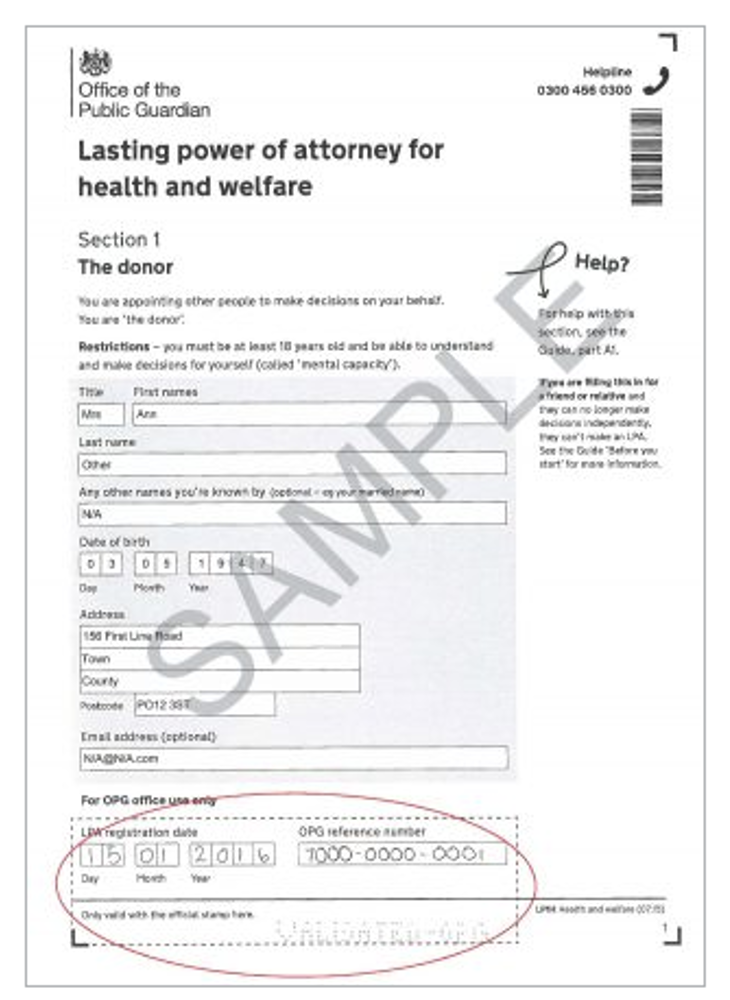

- Ask to see the original Lasting Power of Attorney document (for LPAs registered pre- 17.7.2020). The picture below shows the stamp and perforated confirmation you would expect to see on a registered document.

- If the LPA was registered on or after 12.7.2020 the attorneys and donor will have been issued with an activation key (a number) to create an on-line account. The online service enables people to:

- view a summary of the LPA

- keep track of people or organisations given access to the LPA

- see how people named on the LPA are using the service

- request or replace an activation key

The LPA reference number will be required in addition to the activation key. This is a significant improvement to the efficiency of checking LPAs. Full details of the service can be found on the Gov.UK use a Lasting Power of Attorney page.

- Clarify how the attorneys can act if there is more than one attorney; this could be jointly (together) or severally (separately) – and might differ for different decisions.

- An LPA for Health and Welfare can ONLY be used when the donor has lost capacity to make the specified decision. When making the LPA for Health & Welfare the donor will have made an important decision whether or not to give their attorney(s) authority to give or refuse consent for life sustaining treatment

- An LPA for Property & Finance can be used EITHER as soon as it is registered or only when the donor loses mental capacity. The donor will have selected which option they wanted when making their LPA.

In this hearing, Peter Mant (Counsel for the Trust) questioned why events “took the turn they did” and asked “what can be learned and how can proper respect be given to Power of Attorney and to those that have this in their favour.”

I would echo this statement and be interested to find out how the Trust will be supporting clinicians in better understanding of Lasting Power of Attorney in future.

2. Do Not Attempt Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation

Moving to the second framework, Do Not Attempt Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation (DNACPR), there is a similar lack of evidence that the correct process was in place for Mrs W.

The attorneys had been told that Mrs W was not for cardio-pulmonary resuscitation, and they did not agree with this.

As with Lasting Power of Attorney, DNACPR is underpinned by the Mental Capacity Act . Another key legal framework with relevance to DNACPR is the Human Rights Act 1998. Both these acts are referenced in the Resuscitation Council UK guidelines decisions relating to cardiopulmonary resuscitation

Cardiopulmonary resuscitation or CPR is an active intervention or treatment aimed at restarting the heart in someone who has experienced a sudden cardiac arrest. The important word is treatment; like any medical intervention, the benefit and burden must be balanced. CPR is not an appropriate action for someone who is approaching the end of life and, contrary to popular belief, is not an action that can be requested. CPR can however be refused by an individual with capacity or by an attorney who has been granted option A decision-making via a Lasting Power of Attorney.

The NHS information Do not attempt cardiopulmonary resuscitation decisions updated in March 2021, makes this explicit with the statement: “It is important to understand that nobody has the right to demand CPR, so the decision may not change if there was a good clinical reason for it (for example, your heart, lungs or other organs are struggling to work). The doctor should explain their reasons and ask about your wishes and preferences“.

At the hearing for Mrs W on 10th December 2021, the applicant, represented by Katie Gollop QC , requested a review of the DNACPR decision:

“The son also wanted the DNACPR removed (again on an interim basis), disclosure of medical records, and an independent second opinion from an expert.”

DNACPR is an emotive subject. I have seen first-hand, and have personal experience of, DNACPR conversations handled poorly with little professional understanding. It is never appropriate to ask “do you want your mother resuscitated”: the decision to attempt CPR is a medical one. What is always appropriate and indeed part of the legal framework, is the necessity to consult with a person about the DNACPR decision.

The ruling concerning Janet Tracey (R (Tracey) v Cambridge University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust & Ors [2014] EWCA Civ 822) concluded that: “there had been an unlawful failure to involve Mrs Tracey in the decision to impose the first DNACPR notice, in breach of Article 8 ECHR for the following reasons:

- Since a DNACPR decision is one which will potentially deprive the patient of life-saving treatment, there should be a presumption in favour of patient involvement. There need to be convincing reasons not to involve the patient.

- It is inappropriate (and therefore not a requirement of Article 8) to involve the patient in the process if the clinician considers that to do so is likely to cause her to suffer physical or psychological harm. Merely causing distress, however, would not be sufficient to obviate the need to involve the patient.

- Where the clinician’s decision is that attempting CPR is futile, there is an obligation to tell the patient that this is the decision. The patient may then be able to seek a second opinion (although if the patient’s multi-disciplinary team all agree that attempting CPR would be futile, the team is not obliged to arrange for a further opinion).”

The later Winspear judgment Elaine Winspear v City Hospitals Sunderland NHS Foundation Trust [2015]EWHC 3250 (QB) in 2015 made clear that the principle of consultation applied both in the presence and absence of capacity:

“As Blake J noted: “[t]here is nothing in the case of Tracey or the Strasbourg case law to suggest that the concept of human dignity applies any the less in the case of a patient without capacity” (paragraph 45). He therefore accepted the claimant’s case that the core principle of prior consultation before a DNACPR decision is put into place on the case file applies in cases both of capacity and absence of capacity.”

There would appear to have been be a similar lack of consultation or discussion regarding DNACPR for Mrs W and I hope this will be included as part of the SUI.

What next? Organisational accountability

Ensuring correct frameworks and best practice requires appropriate education. Equally important is a monitoring and assurance element.

The shocking feature for me in attending the hearing is what appeared to be a systematic failure in process.

I am left wondering how decisions such as DNACPR and CANH are monitored within the Trust, how decisions are audited and how best practice can be assured.

It is the details of this case that matter so much, and the apparent lack of reference to legal frameworks, alongside a lack of communication with a family.

I noted that the family were fighting for the interventions not as a cure or believing their mother’s condition was reversable, but so she could “move to home and end her days there”.

I find it profoundly sad that there is no evidence of proactive Advance Care Planning and eight years after the Janet Tracey ruling we are witnessing yet another family who have not been included in decision making.

My deepest sympathies are with Mrs W’s family. They are contending with grieving for both parents, and with an investigation into the death of their mother.

I remain mindful that there is a very human story behind the facts of the case and respectful of the opportunity I had to be in Court to witness it.

My sincere wish is lessons are indeed learned by this Trust – and beyond.

Clare Fuller RGN MSc is a registered nurse with a career dedicated to Palliative and End of Life Care. She is an advocate for proactive Advance Care Planning and provides EoLC Service Analysis and bespoke EoLC Education. Clare hosts Conversations About Advance Care Planning. She is also a Lasting Power of Attorney Consultant and director of Speak for Me LPA. Connect with Clare on Twitter @ClareFuller17

Photo by Benjamin Elliott on Unsplash

Reblogged this on Residential Forum.

LikeLike