by George Palmer, 26th February 2024

Many people are unaware that you can appoint another person to make decisions on behalf of your health and welfare and/or your financial affairs if you ever lose the capacity to make these decisions for yourself. This involves appointing someone as your Lasting Power of Attorney (LPA). You can check this out on the government website.

Perhaps because people don’t know it’s possible to do this, or perhaps because they don’t think it’s necessary until the late stages of an illness, many people leave making their applications until their decision-making capacity to appoint an attorney is questionable. This can mean their application is rejected You can only appoint someone as your attorney when you have the mental capacity to decide to do so (and the fact that you do have such capacity has to be recorded in the application by a ‘certificate provider’). This case is about someone who may have left it too late to appoint an attorney. The Public Guardian took the view that she lacked capacity to make that decision at the point she completed the application forms.

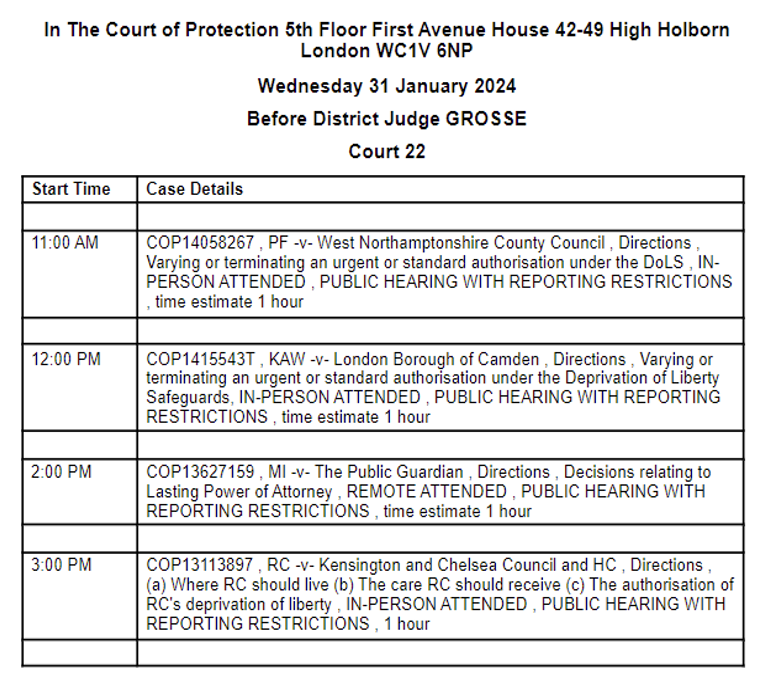

The hearing I observed – with the support of Daniel Clark from the Open Justice Court of Protection Project core team – was held on 31st January, at 2:00p.m before District Judge Grosse. It was listed as concerning a Lasting Power of Attorney (LPA) – see the third case on the list below, taken from Courtel/CourtServe (COP 13627159).

I knew very little about Lasting Powers of Attorney and so had a huge interest in this hearing. I was fortunate enough that Daniel could provide me with previous blog posts published by the Open Justice Court of Protection Project and these helped me to gain an initial understanding of what a Lasting Power of Attorney is and how it works (e.g.The logic, law and language of Lasting Power of Attorney: A case before Hayden J).

After requesting the link, I received the Transparency Order (TO) for the hearing at 9:03 a.m. that morning, five hours before the hearing, allowing plenty of time to read its terms and restrictions. The TO was easy to understand, and set out in the usual terms, prohibiting the publication of any information that will identify (or is likely to identify) the protected party, her family, or where they live, or their contact details. It was sent to us prior to the hearing, which is quite unusual: as usually we have to ask counsel for them, if we ever receive one at all. However, this was the second time running where I had received the TO before the hearing, which is a great way of promoting open justice and ease of access for public observers.

Armed with my new insight into LPAs and the TO, I was confident that, with a brief summary by the court on the facts of this case, I would be able to keep up with the legal arguments being made by both parties. Sadly, however, there was no opening summary of the facts and background to the case – despite guidance from the previous Vice-President of the Court of Protection. Although DJ Grosse did ask all public observers whether they had read and understood the TO (to ensure none of us would act in contempt of court) and was highly welcoming and friendly, it’s unfortunate that the judge did not follow the guidance and ask counsel to provide an opening summary, since this would have made a real difference to my understanding of the case and supported the judicial aspiration for open justice.

Instead, we had to pick up the facts of the case as we went along as they were mentioned at various points throughout the hearing. From the perspective of an observer, this made it all a bit disjointed and difficult to follow.

Although we asked for the Public Guardian’s position statement, it was never received, so we weren’t able to fact-check after the hearing either. The failure to supply a position statement may be because I can’t be sure who the barrister was. The judge and counsel for the Public Guardian were in a physical courtroom, and the judge simply referred to Counsel as “Mr Francis” during the hearing. We deduced that he might be Thomas Francis of 45 Gray’s Inn Square based on the picture on his Chambers’ website – but we could be wrong about this. An email to the court sent shortly after the hearing, asking for counsel’s first name, went unanswered.

I learned that the case concerned the validity of an LPA that named the respondent, AF, as an attorney. Due to the lack of opening summary and position statement, I’m not sure whether both types of LPA (i.e. health and welfare and finance), or just one type, were being discussed.

AF’s mother, MI, had revoked an earlier LPA and then made two more of the same type, both appointing AF as her attorney. The Public Guardian, argued that MI lacked the relevant mental capacity to make the LPA (or one of them, if in fact there were two). Furthermore, it was the view of the Public Guardian that if the court found MI had in fact had the capacity to make her LPA at the time she made it, the LPA should nevertheless now be revoked.

I understand that a doctor’s witness report had been received which stated that the mother did NOT have capacity at the requisite time (when she purported to make the LPA).

AF argued against this, stating that MI’s lawyers, as well as her own treating doctors, had assessed MI as having the capacity to sign the LPA at the material time.

I was unable to ascertain from the short hearing whether the certificate provider (i.e. the person who fills in the form stating the individual has the capacity to make the LPA) had been the mother’s lawyer or her doctor, and I found it a highly worrying possibility that an individual such as MI can go through all the legal procedures correctly to have her past capacity rejected later down the line by another doctor.

In addition, AF was adamant that the care she had undertaken for her mother over the past four years, all – she claimed – with her mother’s consent, should enable her to be granted LPA on behalf of her mother, whom she clearly cares for and wishes to help. This highlights the disadvantage that some litigants in person may face: an argument that sounds perfectly reasonable may not be on strong legal ground.

In not wanting to prolong the case for any longer, DJ Grosse proposed two weeks for AF to respond to the doctor’s report, before issuing a final hearing, not seeing the benefit of any additional direction hearings.

In anticipation of this final hearing, DJ Grosse noted that AF was calling from a foreign jurisdiction: namely, America. Recalling a case in which there were issues with a party giving evidence remotely from Pakistan, and in which they had to give evidence in a UK Court, she proposed that AF would potentially need to seek permission from the UK consulate in the state in which she lives regarding giving evidence. Mr Francis was offered his support in advising the respondent on how to do this and the impact it would have on the proceedings.

Final thoughts

Cases such as these emphasise the importance of LPAs alongside other existing frameworks such as Advance Decisions to Refuse Treatment. Such devices allow individuals, particularly those who have strong desires about their future treatment, should they ever lack capacity, to make legally binding decisions on behalf of their future selves. Other kinds of Advance Care Planning (e.g. advance statements) can be equally important toolsm and have legal standing, though an advance statement is not legally binding.

While some may argue that no one can truly know what they will want until such a time comes, many feel that the ability to allow individuals who know and care about you to make decisions on your behalf, instead of, in this case, a public body, is a far more comforting and suitable solution. This is something that struck me enormously during this case, where a daughter, who loves her mother dearly, wishes to make decisions on her mother’s behalf that she is confident is what her mother would have wanted. Even more worrying, is the potential vulnerability we all face in having the state tear down the very protections we have tried to put in place to protect our incapacitated future selves.

I look forward to attending future hearings in this case, and continuing to learn more about LPAs and the issues individuals face in attempting to make them, and the challenges their families and would-be attorneys face in enforcing them.

It seems apparent that many individuals may not think about making such applications until their capacity to make such decisions has potentially been reduced, making such applications far more complex and open to challenge by public bodies.

While public bodies are required under the Mental Capacity Act 2005 to make decisions in the person’s best interests (which take into account the person’s own wishes, but are not determined by them), some people would prefer those decisions to be made by someone they know and trust. That’s why Lasting Power of Attorney is an important legal tool. I now believe that all of us , no matter our age, should seriously consider making an Lasting Power of Attorney and/or an advance decision or advance statement.

This case will return to court on Friday 26th April 2024, and will be listed for a full day (remote) hearing.

George Palmer is a third-year law student at the University of York and an aspiring clinical negligence barrister. He hopes that observing Court of Protection hearings will give him a greater knowledge and understanding of the legal system, as well as provide him with the foundational principles of a successful barrister, which he hopes to take into practice in future.