By Claire Martin, 15th April 2024

A hearing before HHJ Beckley on 18th March 2024 (COP 1347207T) started off with counsel for P (Alison Harvey) describing the person at the centre of the case as “a most distinguished man’”. He is used to living in Kensington & Chelsea and wants to go back there to live.

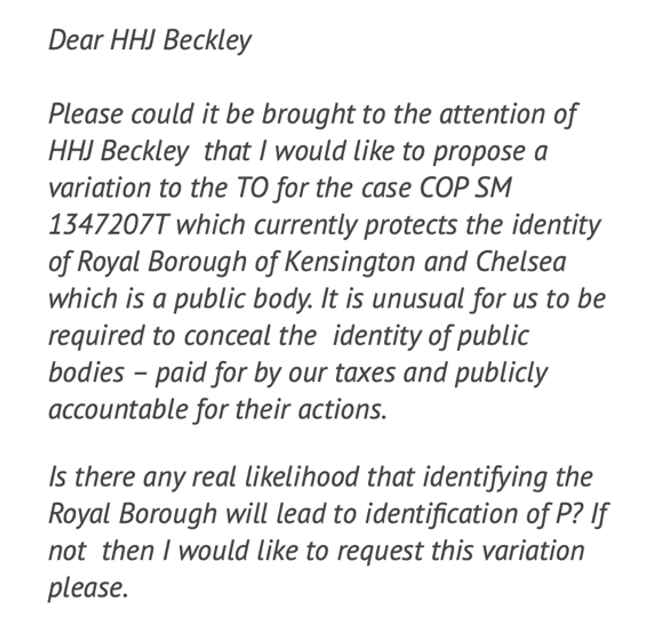

I am able to name the Royal Borough of Kensington & Chelsea (RKBC) because – although the Transparency Order (TO) that observers are served originally stated that RBKC could not be named – I emailed the judge before the hearing started and asked him to consider changing (‘varying’) the injunction.

At the start of the hearing, HHJ Beckley said that this issue had been “helpfully raised” and that “… the TO unusually, and in my view erroneously, says RBKC shouldn’t be identified. There’s no reason that RBKC shouldn’t be identified. That will be taken out of the order“.

We have found that (as this case illustrates) it is much easier to vary a Transparency Order before or during a hearing than afterwards. So, it really helps to be sent the TO prior to a hearing.

The Hearing

P (I am not sure how old he is) was a professional man in the STEM sector. He has lived where he currently resides since 2020.

From 2010 he is said to have experienced depression and alcoholism and then in 2013 he had a brain injury that has affected his short-term memory and has left him with seizures, which have led to further injuries. Up until some time in the mid-late 2010s he lived with his mother, but she moved out because she felt unsafe. Then he was evicted from the family property and had a further seizure in 2018 which eventually led to him living where he lives now.

P is the applicant in this case, via his ALR (who kindly shared their Position Statement so that I could better understand the current situation). The application was to challenge the authorisation of P’s deprivation of liberty at the place where he currently lives. The respondent is the Royal Borough of Kensington & Chelsea. Two family members, his niece and his sister, were also (remotely) at the hearing, but they are not (yet) parties in the case.

P really does not want to be living where he is now. He has consistently stated this. Counsel for P said that “proceedings have been DOGGED by delay. By the last hearing we reached a state of considerable vexation from his ALR” (her emphasis). The proceedings have been ongoing since March 2022 and “we have no tangible progress to show for it for [P] in terms of getting back to the area where he wants to live”.

P had been assessed by various care homes, and had repeatedly been turned down for a place to live. However, on the morning of the hearing, a company (which had previously declined to offer a place) had come forward with a place for P.

This was presented as an opportunity for P. He hadn’t yet seen it though, and had “turned his nose up” at it, being in a ‘less smart area of Kensington and Chelsea’. His counsel said “we hope that when he visits it he will feel more positive about it”.

However, it transpired that P’s family was somewhat concerned about the proposed move. The court was told that “they are involved at every step. Ultimately they are consulted and involved rather than having power to force the court to complete options“. Alison Harvey, Counsel for P, proposed a plan: “… an initial transition meeting, an opportunity for the family to see [the care home] so they can take a view, and then a transition plan which would include provision for [P] to visit the placement. Advice would be sought as to how to present that to him, make it as positive as possible. See if we can reach agreement on a transition plan. We are dependent on [P] wanting to go. That remains a question for all of us.”

Other options would be considered in parallel, in case it didn’t work out. The relief in P’s counsel’s voice was palpable when she said “having been through a very rocky period we have achieved for the first time a concrete option to explore within Kensington & Chelsea, and that’s very exciting for everybody“.

Counsel for RBKC (Catherine Rowlands) and P’s family seemed less excited about the developments.

Catherine Rowlands said, “Your Honour, the proposal that [P] should go to [the care home] is not set in stone. He has at the moment said that he’s not even willing to look at it“.

RBKC would place P on the waiting list for a council property (which would require a care agency for independent living) and the social worker was to do that. This was a “fallback” (said the judge) and “this isn’t going to magic a property rapidly“.

The judge then addressed P’s family. P’s sister spoke first. She said that she was concerned about P moving out of the place where he is now because of a potential reduction in support. She mentioned that he currently receives psychological support from a psychotherapist and that he has epileptic fits and is concerned about whether he will receive 24/7 support. A further concern is access to alcohol and potential trouble with the police.

P’s niece (who is a doctor) expressed pleasure that progress had been made, though she had reservations. She was concerned that the place being proposed now had, only the previous week, said that their care home was not appropriate for P, “so we’ve done a 180“. She also said that, despite being told that they would receive communications about the case, the family received everything “last minute” and that she felt this was “being pushed through … it feels like due diligence isn’t being done”. She outlined significant care concerns: “The website [of the proposed care home] mentions offenders and ex-offenders. My uncle is very vulnerable. With my healthcare hat on … he needs a consultant neurologist like he has in [current residence]. Who’s going to do that? Timing is my big concern – the neuropsychologist has concerns about [GP and hospital appointments].”

Counsel for RBKC and (I think) P’s social worker, who was also at the hearing, both tried to reassure the family that “transition planning is going to be thorough“.

The judge, similarly, stated: “Again, just to set [sister and niece’s] minds at rest. It’s not proposed that [P] will move before the next hearing. This is a best interests decision. […] [It has been] absolutely clear throughout the proceedings with [P] … he wants to be in RBKC. I do take into that view, his family’s views.”

So, that was the plan. P was to be encouraged and supported to go to look at the new proposed place to live, P’s social worker was to be authorised to make an application for social housing in RBKC as a ‘fallback’ and the family was to be involved in considerations.

At the end, P’s niece spoke up: “One request I would have, in front of everybody, if documents are being submitted please can we have them in plenty of time? The cynic in me says: do we get them late so we can’t have a voice? You will hear my voice! I ask court that everyone sticks to time and we have two weeks”.

She explained that time is needed to translate and discuss the proposals with P’s mother, whose first language is not English. The judge engaged with this request, suggesting that the Local Authority’s evidence should be received a month before the hearing.

Reflections

This case had clearly been long and arduous for all concerned. It was clear that there is not a preponderance of specialist places to live for P, that can meet his needs and that are in his preferred area to live. Finding the balance between those two things has clearly been challenging.

There was dispute between P’s counsel/ALR and the Local Authority about who should be doing what and paying for it. For example, at one point, searching for potential properties to buy was raised as an option, but counsel for the Local Authority was clear that “It is not the case where we intend to go and look for somewhere in the property market. It is not the job of RKBC”. Who should make the application for social housing was a further issue. Counsel for P was firm: “May I say … the legal aid agency wouldn’t fund [ALR] to fill out any of those forms. There’s no way they’d pay him“. The judge confirmed that this was authorised to be the Social Worker’s role.

This case seems beset with issues, not only by finding an appropriate place for P to live, but also with budgets and who will do what, when. This is the way of things, I understand. I know from my own experience that it is the same in the NHS. People get lost in the melee though – and, even when professionals try their best, delays inevitably happen. Such has been the impact on P’s life here, it seems.

I thought some of the language used was interesting. P was presented as “a very distinguished man”, which made my ears prick up. I am reminded of medical letters that often start off “I had the pleasure of meeting this delightful lady….’” or some such accolade. What about people who are not “distinguished” or “delightful”? Are those adjectives relevant? Maybe they are. We were told that, although where P was living was a specialist placement and it has rehabilitated him: “…. it is not where he wants to be. He identifies very strongly with Kensington & Chelsea. The borough is central to his identity, as a resident of Kensington & Chelsea, and as a very smart man of a very smart suburb“.

Perhaps that is the case. Maybe I am being a bit picky here. I wondered why that way of describing him was chosen, rather than, say, that P previously lived in Kensington & Chelsea and this is where he feels at home and would prefer to live. P was also very keen to be registered with his previous GP, with whom it seemed he had a good relationship. This was presented as follows: “If he is in the borough, the surgery which he is very fixated on is more likely to accept him as a patient.” It made me wonder whether the rest of us, when thinking about things that matter to us and that we can autonomously pursue, would consider ourselves to be “fixated” on those things?

These are just little words, here and there. I think, though, that they might be more readily applied to others, rather than how we would choose to describe ourselves, when we speak for ourselves.

The next hearing for this case is planned for Wednesday 5th June at 10.30am.

Claire Martin is a Consultant Clinical Psychologist, Cumbria, Northumberland, Tyne and Wear NHS Foundation Trust, Older People’s Clinical Psychology Department, Gateshead. She is a member of the core team of the Open Justice Court of Protection Project and has published dozens of blog posts for the Project about hearings she’s observed (e.g. here and here). She tweets @DocCMartin

One thought on ““A most distinguished man” ”