By Eleanor Tallon, 3rd September 2024

Editorial Note: The judgment (making this hearing private) has now been published: Stockport MBC v NN & Anor [2024] EWCOP 51 (T1)

I was not able to observe this hearing because the protected party, N, said she did not want an observer as “she doesn’t know who they are or what their ethics and values are”, and the judge ruled that a public hearing was not in N’s best interests.

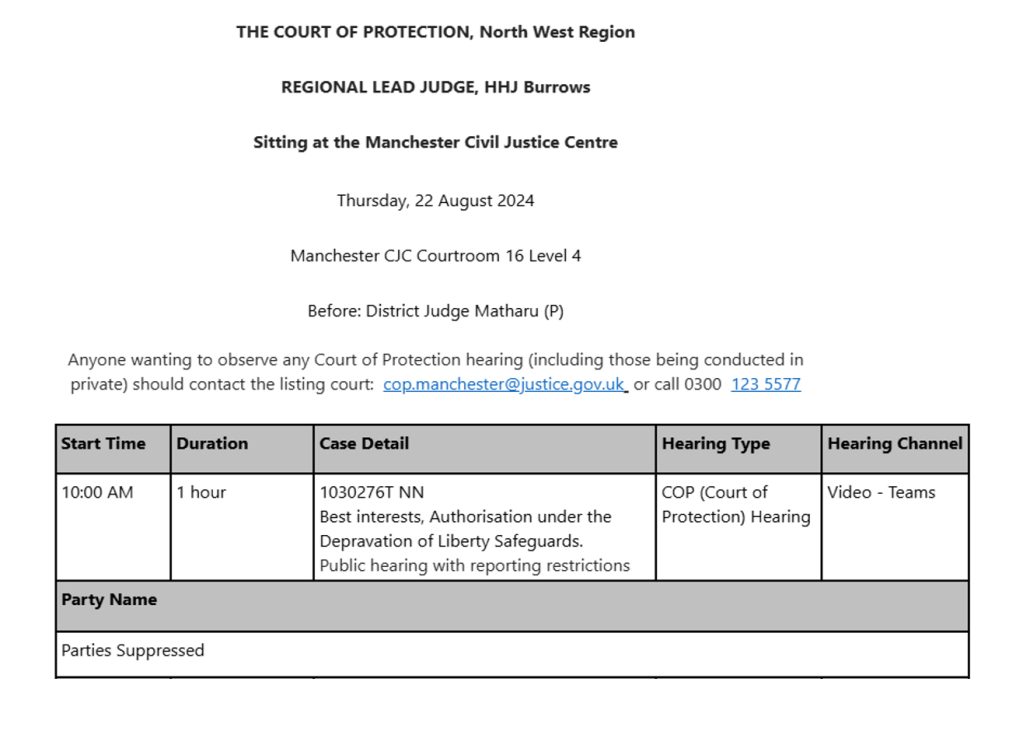

The case (COP 1030276T) was listed as a public hearing (see screenshot below). I gained access via the link sent by court staff at precisely 10am on 22 August 2024.

My observation was limited to hearing submissions about restricting public access to the hearing and an ex-tempore (oral) judgment. The judge’s decision was based on a report of N’s distress at having an observer attend, and the fact that the Official Solicitor acting on behalf of N, did not agree to my attendance. I was asked my position on the matter, before the judge ruled that it was not in N’s best interests to continue the hearing in public, so it became a private hearing, and I had to leave.

This blog will go through the judgment (on public access to the hearing), with a reflection on the challenges of balancing P’s privacy with the values of open justice. I will also discuss the court rules in relation to public and private hearings, which differ between the Civil Courts and the Court of Protection. It seems that even judges can sometimes misapply the rules. Finally, I will consider why advance planning is important when deciding whether proceedings should be made private – not only for the benefit of the protected party, but also to avoid a false impression of transparency being given to the public.

The hearing

I requested access to the hearing by email at 7.52pm on 21st August 2024. I then followed this up with a further request marked ‘urgent’ at 9.08am on 22nd August, as I hadn’t received the link or a transparency order. By 10.00am I still hadn’t received anything, so I telephoned the court, but while waiting for the phone to be answered, I saw the link to the hearing pop up in my emails. I quickly gained access to find 12 attendees waiting for DJ Matharu to join, including the following:

- Barrister Varsha Jagadesham (who I later learnt was counsel for N via the Official Solicitor)

- Barrister Mungo Wenban-Smith (who I learnt was acting for the first and second respondents, and I assumed from the email addresses that the respondents were the local authority and the ICB, and this was later confirmed)

- Legal professionals from Hampsons and Bindmans (presumably the instructing solicitors)

- Various professionals from the local authority, one from health and one from a care home organisation

The protected party, N, was not present, and I was the only member of the public attending.

At 10.10am, DJ Matharu came on screen. She explained that she had just spent some time communicating with Ms Jagadesham (counsel for N) about an observer wanting to join. She elaborated: “I have had conduct of this case for a number of years, through which N has been actively involved in her own case. It was important for counsel to inform her that an observer request had been received. Ms Jagadesham you have informed N, what is your view?” Before counsel responded, the judge emphasised that the starting point was that this was a public hearing.

Counsel for N replied: “I have spoken to N and she said no, she does not want a public observer attending as she doesn’t know who they are or what their ethics and values are. There is the potential for distress and the Official Solicitor does not consent to an observer. This is an unusual position. The Official Solicitor is concerned that public attendance would not be in N’s best interests, given it could cause real distress. N is already fairly heightened. The social worker assisted her to speak with me and she needed support to calm her down. It took a few attempts to close the call. Given that N would be very unhappy with a public observer, and she’s already upset that the court has been invited to conclude the matter today, having a public observer could be more upsetting. We are not opposed but the Official Solicitor does not consent, and it must be considered whether it would be in her best interests under section 4 of the Mental Capacity Act.“

The judge then turned to Mungo Wenban-Smith (counsel for the respondents), pointing out that he had been involved in the case long-term and she asked what his position was. He said: We wouldn’t oppose an application to exclude observers, and listening to the submissions on behalf of N, distress is likely. I refer to your consideration, but we wouldn’t oppose a private hearing, should this support a smooth hearing and N’s best interests.

The judge then addressed me: We have an observer, Ms Tallon. We have discussed the paramount considerations: what do you say? I wanted to say that I was observing as a volunteer with the Open Justice Court of Protection Project, and that my ethics and values are aligned with the focus of the Project – to ensure people are being treated fairly by the court. However, I wasn’t expecting this to happen, and I had not anticipated the need to champion open justice under such circumstances. I also didn’t want to distress N or delay the hearing further and I was acutely aware of the discomfort I would have felt, if the judge had allowed me to observe against N’s wishes. I responded: “Good morning judge. I don’t wish to cause any distress, and, on that basis, I am happy not to observe the hearing“.

The judge then continued: “I have to give a judgment as to the rules and I will be brief because I’m conscious of the agitation of N if there is delay. The case is concerning N, and it’s been before me many times, supporting judicial continuity. A public observer request was made late last night. This is a public hearing and it’s important to notify the legal teams of such requests. This is in the knowledge of N being actively involved in the case with regular and frequent participation. Counsel for N and the Official Solicitor feel that distress will be heightened. She does not want an observer in this case, and this would displace the presumption of a public hearing. I need to take the court rules into account, and I must have regard to N’s best interests. Her best interests would not be served by an observer attending the hearing. N is a private lady, she’s treated with dignity, and her voice shall be heard and is often heard. There are finely balanced outcomes. N was going to participate, but this caused her anxiety. Ms Tallon has been gracious. Having heard that, she is willing to withdraw. Yet I have to give my judgment. The facts are that the court welcomes observers, but on the facts of this case, it is not in N’s best interests. The Civil Court rules are imported into the MCA and the hearing must be public unless one or more of matters at CPR 39.2 paragraph (3) apply. At subsection (c) it involves confidential information and personal matters, and at subsection (d) it would not be in the best interests of the protected party, if anyone was to observe. The observer is not opposed. Do you have anything to add Ms Tallon?“

I responded: “No, thank you, judge. I will remove myself from the link now“.

I left the hearing at 10:24.

Balancing the right to freedom of information (Article 10) and the right to privacy (Article 8)

As an Independent Social Worker, I am regularly instructed to provide expert opinions on mental capacity and best interests. My approach to this always centres around enabling decision-making capacity, and failing that, supporting the person’s participation in decision-making and aligning decisions with their wishes and feelings as far as possible. Yet there are times when there are competing values. Often this is in the context of protecting a person from risks of harm versus protecting their autonomy, but here the situation was different.

The balance was between, on the one hand, the ECHR Article 10 right to freedom of information and the value of open justice (which also offers a further level of quality assurance that the courts are operating fairly) and, on the other, N’s ECHR Article 8 right to privacy, and her sense of dignity and participation in the proceedings. It was a natural response to willingly concede to the hearing being made private, as it went against the grain for me to be the very reason N did not participate in her own hearing, regardless of how well intentioned my reasons were for wanting to observe.

A similar case before Hayden J

Having the discussed the course of events with Celia Kitzinger, co-director of the Open Justice Court of Protection Project, she drew my attention to a previous blog, which reports a hearing before Hayden J, in which the protected party ‘Ms P’ “strongly objects to members of the public being present” (“Privacy, capacity and the judge’s communication skills”). That case was different, in that counsel (including Ms P’s counsel), were content for the hearing to be in public, and Mr Justice Hayden refused Ms P’s request for the hearing to be held in private. He explained the Transparency Order to her, and said that her name and identity could not be revealed, and highlighted the importance of open justice. The judge said: “Like many cases that come to the Court of Protection, the applicant Trust is asking the court to declare legal a course of treatment that is highly invasive concerning an adult whose capacity is in issue. This sort of case is of human importance in a mature, civilized, democratic society and it manifestly engages issues of civil liberties. In society at the present time, every day, a whole gamut of civil liberty issues are raised and I cannot think of any period when it’s been more important for the court to be vigilant to maintain civil liberties.” (Mr Justice Hayden, as reported in the blog post)

Although Hayden J communicated sensitively and reassured Ms P in an exemplary manner (and she did in fact participate fully in the hearing), the public observers still felt a tangible level of unease and guilt whilst attending a hearing against the wishes of the protected party where the person felt her private affairs were laid bare.

I reflected on what I experienced in the small part of N’s hearing I attended, and I completely empathise with N. On a personal note, if I was subject to decisions being made about my life by professionals within a court arena, it would fill me with an intense feeling of anxiety and powerlessness, which would only be increased by having unknown public observers watching from a virtual gallery.

Yet, from a professional perspective, I’m also mindful that there can be errors made, closed cultures and a (sometimes devastating) misapplication of the MCA within all professional domains.

The Court of Protection is the responsible body for setting the legal precedent and providing rulings which direct wider practice under the MCA. Open justice is therefore vital to safeguarding the rights of individuals, exposing abuse of power, and allowing for public scrutiny over decisions made.

Court rules and practice directions

I was puzzled by the judge’s use of the Civil Procedure Rules (CPR 39.2) in the Court of Protection. This perplexity was based on my understanding that the Court of Protection Rules and Practice Directions would apply.

With Celia’s help, I researched this (thank you Legal Twitter/X), and it was confirmed by lawyers that the Court of Protection Rules 2017 are the primary procedural rules of the Court of Protection.

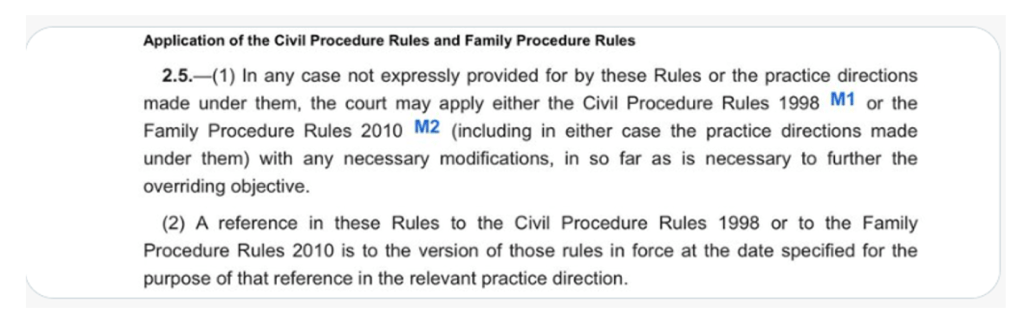

The Civil Procedure Rules are incorporated into the Court of Protection to fill in any ‘gaps’ in the COP rules, as necessary (see Rule 2.5 of the Court of Protection Rules, copied below).

So, it seems that the Civil Procedure Rules can be applied in the Court of Protection but only in situations where the Court of Protection Rules don’t provide for the issue.

But the Court of Protection Rules do cover decisions about making hearings public or private (at part 4.3).

This is what Practice Direction 4C says:

2.1. The court will ordinarily (and so without any application being made)—

(a) make an order under rule 4.3(1)(a) that any attended hearing shall be in public;

and

(b) in the same order, impose restrictions under rule 4.3(2) in relation to the publication of information about the proceedings.

2.5. (1) In deciding whether there is good reason not to make an order pursuant to

paragraph 2.1 and whether to make an order pursuant to paragraph 2.4 instead, the court

will have regard in particular to—

(a) the need to protect P or another person involved in the proceedings;

(b) the nature of the evidence in the proceedings;

(c) whether earlier hearings in the proceedings have taken place in private;

(d) whether the court location where the hearing will be held has facilities

appropriate to allowing general public access to the hearing, and whether it would be

practicable or proportionate to move to another location or hearing room;

(e) whether there is any risk of disruption to the hearing if there is general public

access to it;

(f) whether, if there is good reason for not allowing general public access, there also

exists good reason to deny access to duly accredited representatives of news

gathering and reporting organisations.

It appears that the judge made an error in applying the Civil Procedure Rules where the Court of Protection Rules should have been applied instead.

It’s quite possible that the outcome would have been the same regardless of which set of rules were applied, but the court should, nonetheless, be clear and accurate about the basis on which decisions are made.

Of course, not all judges are Court of Protection specialists, and I imagine that it isn’t easy to move between different courts, with a myriad of applicable laws, rules and regulations depending on the type of case.

This apparent legal error also points to the value of having an observer in court who can detect a potential misapplication of the law, research the matter with guidance from experts, and report on it, thereby (hopefully) improving the justice system.

It is also a credit to open justice that there are lawyers who are supportive and instrumental in helping public observers and bloggers to understand the law and who are willing to contribute directly in a very pragmatic way, to enhance public knowledge and advance the judicial aspiration for transparency.

Further reflections

I admired that DJ Matharu held N’s privacy and dignity in high regard, and she was clearly committed to N’s participation.

Yet with reflection on the court rules, it may have been less stressful for N if the court had thought ahead and made the hearing private in advance, rather than this being triggered at the point of an observer request being received – particularly as observer requests can usually only be made after about 5pm on the evening before the hearing at the earliest (please see this blog post which explains why: Why members of the public don’t ask earlier to observe hearings (and what to do about it)).

Given that N had been such an active participant in the hearings over some years, discussions about whether or not there should be public observers and the principle of open justice as it applied to this case could have been held much earlier in the proceedings. Then if N objected to observers, her counsel could have prepared a formal application to make the hearing private. It felt to me that this hearing was, under the circumstances, inappropriately designated as public. Forward planning would have also allowed for clarity as to which rules to apply and made for a ‘smoother’ hearing for all concerned.

In PBM v TGT & Anor [2019] EWCOP 6, Francis J made the hearing private because “(f)rom the outset, PBM expressed considerable concern about the possibility of members of the public being present at this hearing”’ – so it seems that in that case, someone raised the matter of public observers with the protected party early on (“from the outset”), meaning that the hearing was listed as private and the situation that arose in this case was avoided entirely. The Court of Protection Handbook also remarks that “there are some situations in which insufficient focus has been paid to the impact upon P of (in effect) broadcasting – or at least, narrowcasting – a hearing” (my emphasis). It seems in this case that ‘insufficient focus’ was given until I asked to observe, which really was too late.*

To conclude, when a judge makes a decision to change the status of a hearing from public to private, there has to be a significant rationale and a careful balancing exercise between ECHR article 8 (right to privacy) and article 10 (freedom of expression). It is not solely a ‘best interests’ decision, as seems to have been implied in the course of this hearing. Ultimately, I believe in this case the right decision was made based on N’s strongly expressed wishes – but advance planning and preparation could have avoided the distress to N, the discomfort I felt having been admitted to a hearing that N didn’t want me to observe, and the hasty misapplication of court rules to the matter. Finally, whether or not a final judgment was made to authorise a deprivation of N’s liberty, I hope that N can find some peace with the outcome, and that her voice continues to be heard.

Eleanor Tallon is an Independent Social Worker, Expert Witness and Best Interests Assessor. Eleanor can be contacted via email eleanor@mcaprofessional.co.uk or through her website mcaprofessional.co.uk and found on LinkedIn or X(Twitter) @Eleanor_Tallon

* I am grateful to Daniel Clark for drawing my attention to this case law and to the Handbook commentary.