By Celia Kitzinger with Jacqui Graves, Sophie Jones, Sophie Keegan, Kris Price, Katharine Shipley and Adam Tanner, 13th November 2020

The person at the centre of this case, Ms P (in her mid-40s), has granulosa cell cancer for which she has declined recommended treatments for more than a year. Recent scans show that the tumour has increased in size over that period, with possible metastases. She’s also in pain. The recommended treatment is now total hysterectomy with oophorectomy. Ms P has continued to refuse consent to treatment.

This hearing (COP 13672912) was before Mr Justice Hayden sitting in the Royal Courts of Justice, on 2 November 2020. It was a directions hearing to agree what needed to be done in order to make a determination of Ms P’s capacity to make her own decision about her medical treatment – and if she does not have that capacity, then what would be in her best interests. Another hearing before the end of November 2020 will make those determinations.

There have already been three capacity assessments by people associated with the Trust, and a fourth (at Ms P’s request) by an independent psychiatrist. All four find that she lacks capacity to make decisions about her cancer treatment. The Trust was now asking the judge to approve another independent psychiatric report of Ms P’s capacity (which he did).

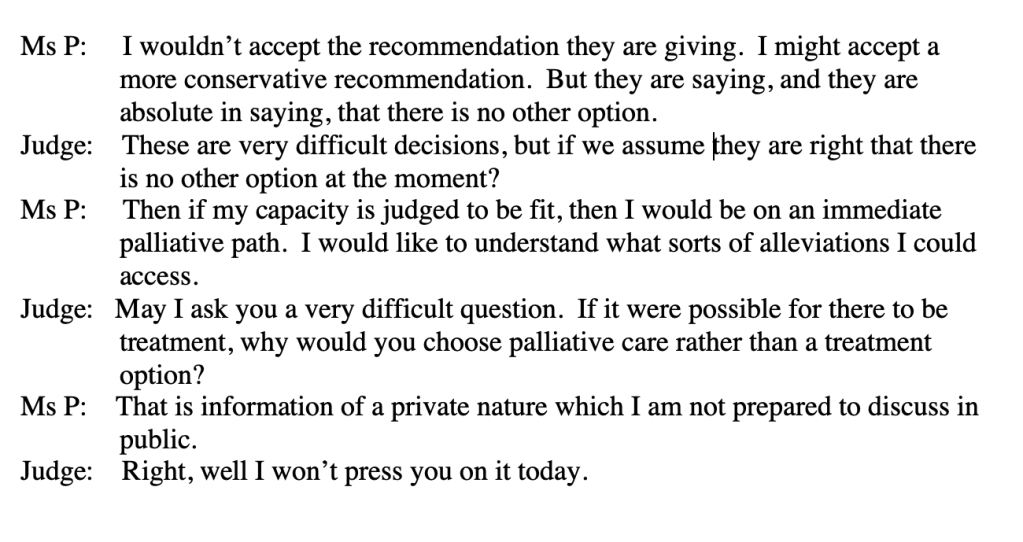

In conversation with the judge, Ms P made it quite clear that if she is found to have capacity she will continue to refuse the recommended treatment.

PRIVACY

The right to privacy turned out to be one of Ms P’s fundamental values and she was fiercely protective of her own privacy during this hearing.

Counsel for Ms P (Debra Powell QC, instructed by the Official Solicitor) opened proceedings by reporting that Ms P “strongly objects to members of the public being present” and that she would like to make an application for this to be a private hearing.

As we have noted before (e.g. here), there can be a gulf between the position taken by P’s legal representative in the Court of Protection and the position taken by P herself. Counsel for P was at pains to point out that the application for a private hearing came from Ms P herself, and did not represent the position of the Official Solicitor. So, the judge asked Ms P why she didn’t want the public to have access to the court.

Ms P was attending via telephone, having declined the opportunity to join the video-platform since she did not want to risk her face being seen. Pressed by the judge to explain why she objects to video-conferencing, she said she was concerned about the security of the software: “there are technological flaws that cannot be protected against”. Explaining why she didn’t want the public present, she said:

“It’s a very private case. I’m aware that I may be asked questions that are of a personal nature that I don’t want to share with the public. It’s to protect my privacy. I don’t believe there’s anything in this case that wouldn’t have been covered by many other cases.” (Ms P)

After checking that both advocates – the applicant Trust (represented by Kiran Bhogal) and the Official Solicitor (Debra Powell QC) were content for the hearing to be held in public, Mr Justice Hayden refused Ms P’s application. He explained the Transparency Order to her, explaining that her name and identity could not be revealed, and highlighted the importance of open justice:

“Like many cases that come to the Court of Protection, the applicant Trust is asking the court to declare legal a course of treatment that is highly invasive concerning an adult whose capacity is in issue. This sort of case is of human importance in a mature, civilized, democratic society and it manifestly engages issues of civil liberties. In society at the present time, every day, a whole gamut of civil liberty issues are raised and I cannot think of any period when it’s been more important for the court to be vigilant to maintain civil liberties.” (Mr Justice Hayden – Note, like all other quotations in this blog post, these are as accurate as we can make them, given that we are not allowed to record hearings so they’re unlikely to be word perfect)

He added “if questions enter a particularly sensitive sphere, I will revisit the application and consider whether I can temporarily ask members of the public to leave”.

Ms P seemed reassured by the fact that her identity would remain confidential. She was referred to as “Ms P” throughout the hearing (unusually, we observers never got to know her real name); nor did we see her on screen. Nonetheless it felt quite uncomfortable to remain in the court given Ms P’s views. Knowing how important it is to Mr Justice Hayden to acknowledge and respect P’s choices, and also his commitment to open justice, I watched him wrestle with the dilemma of which of two competing values to honour on this occasion – and I found myself willing to put my trust in his judgment, his experience, and his knowledge of the case based on the bundle. I was actually reassured that I could trust his decision on this when, later the same day, I logged on to observe another hearing before him and found that an application had been made to hear that hearing, too, in private. On that occasion, Mr Justice Hayden granted the application and asked observers to leave.

Katharine Shipley

As soon as it became apparent that P did not want observers to be present, I felt a strong urge to remove myself from the video hearing out of respect for her feelings. I hung on, half expecting the judge to ask us to leave at the beginning, but clearly open justice is not always entirely compatible with the right to privacy. I felt guilty not leaving though, because P did not want us there and it felt almost sordid that there were a number of us sitting in silence and P had no idea how many of us were there, who we were and why we were listening. The formality of the court process maybe also paralysed me a little to take action to leave. Writing a blog about the case seems important, because of the issues it raises, but I also wonder if this is disrespectful of Ms P’s strong wish for privacy, even with anonymity.

Judge Hayden listened to Ms P, he carefully considered her requests and he explained well the efforts that would be taken to ensure anonymity. He assured Ms P that he would monitor the sensitivity of questions and discussions and said that he would ask observers to leave, if he felt that parts of the hearing should be heard in private. Nevertheless, this was clearly an extremely stressful situation for Ms P, and she was initially unclear about what the Judge’s decision had been regarding observers. I wondered how she was feeling and about the impact of this decision. I hope she had someone to support her.

Sophie Jones

Mr Justice Hayden went into detail of how he will safeguard her privacy throughout the hearing. He explained to Ms P that the court is “crafted to protect P’s identity”. He reassured her by saying “I entirely understand and I am hugely sympathetic for your desire for privacy”. I felt his communication skills with Ms P were exceptional.

Sophie Keegan

After a brief discussion of the application made by Ms P for the hearing to be conducted in private, the Judge (along with counsel for the Official Solicitor), explained clearly and concisely to Ms P why the hearing should be in the public domain. I thought both did this in a respectful way, which sought to reassure Ms P that the hearing would still be highly anonymised despite her application for a private hearing being refused.

Adam Tanner

Hayden J had to weigh the principles of open justice, and the need for the public to be aware of matters of a serious nature, against Ms P’s personal feeling of privacy. Ultimately Hayden said that should matters arise which he felt encroached on Ms P’s privacy, and would stop her fully participating in giving evidence, then he would ask the public to leave at that time. It is a hard balance to strike between these two fundamental principles of the Court of Protection. I believe Hayden struck an acceptable balance whereby we as observers cannot see Ms P, do not know her name, and are bound by an injunction to protect her identity, and yet we are still able to observe and uphold the principle of Open Justice.

Celia Kitzinger

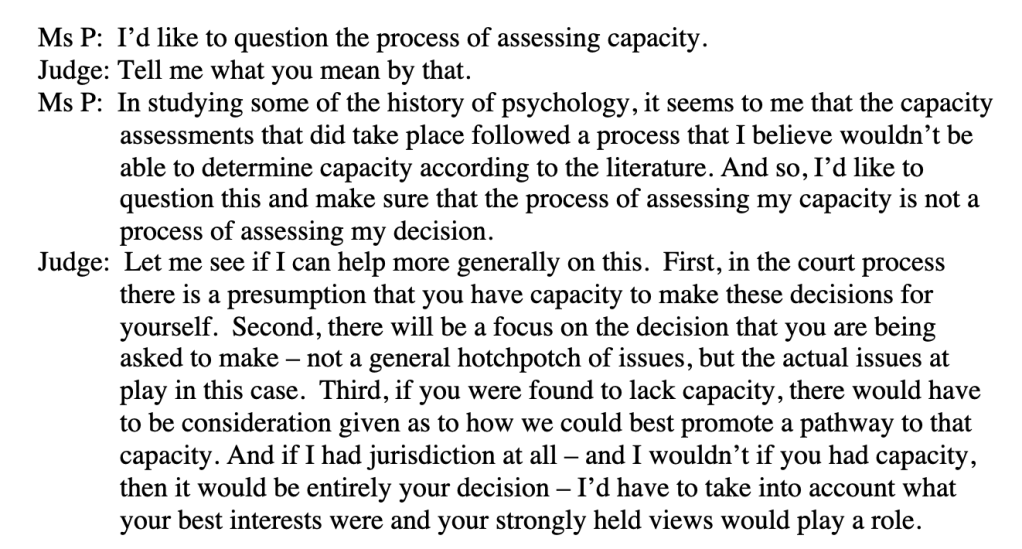

The extent of Ms P’s commitment to safeguarding her own privacy became still more clear as the hearing unfolded. She objected to having to explain – to the capacity assessors and to the judge – why she did not want the recommended surgery. She was being asked this question in order to assess her capacity to make this decision: can she understand, retain and weigh the information relevant to deciding one way or the other? But Ms P does not wish to discuss her reasons with the capacity assessors – and as Mr Justice Hayden pointed out, a person whose capacity is not in doubt would not be required to explain their reasoning. The competent person’s reason for refusing treatment is irrelevant: as Lord Donaldson MR said in Re T (Adult: Refusal of Treatment), “the patient’s right of choice exists whether the reasons for making that choice are rational, irrational, unknown or even non-existent”. Mr Justice Hayden summarised Ms P’s position like this:

“there is an inherent bias in the process because the only way Ms P can establish her capacity is by engaging in discussion about something she doesn’t want to engage in discussion about, and her capacitous coeval would not have to do that.” (Mr Justice Hayden)

Ms P also objected to some of the materials that had been included in the bundle before the court, which she believed should properly be confidential between her and her legal advocates. She said she had not agreed to disclosure of the attendance notes written by her solicitor recording conversations with her, nor to the report written by the Independent Mental Capacity Advocate (IMCA). It is absolutely standard practice for such documents to be included in the bundle before the court. On the other hand, attendance notes for other parties (recording, say, conversations between the Trust and their solicitor) would never normally be disclosed to the court. If a person has capacity, attendance notes are privileged and would not be disclosed: instead there would be a witness statement and P would decide what to say in it.

Referring to the attendance notes, Ms P said, “these are transcripts of a private conversation which I wasn’t told would be revealed”. On the IMCA report:

“I didn’t get to see it, or review it, and I wasn’t asked whether it reflected my views accurately. I also allowed a personal friend of mine to speak to the IMCA, not knowing that she’d report these conversations to the Trust. I would never have allowed this to take place if I’d known what would happen. I was told she was my advocate and would champion my perspective. Her report doesn’t do that. It seems to be a transcription of private conversations, pasted together and handed to the Trust. This is a betrayal. She broke trust with me.” (Ms P)

The IMCA report was (I think) withdrawn from the court bundle after Mr Justice Hayden expressed the view that it “doesn’t appear to add a great deal” and asked, “Given that Ms P values her privacy, and the sensitivity of the point she makes, does this document need to be disclosed?” The information in the attendance notes seemed to be trickier, with counsel for Ms P saying that she would need to take instruction from the Official Solicitor (note – not from Ms P, who – despite being wholly clear and articulate about her wishes, is deemed to lack capacity to litigate).

Ms P’s concern with the way the attendance notes and IMCA records had been disclosed raised important issues that I hadn’t previously considered. The private and confidential relationship normally assumed between advocate and client is here not the case. This is part of the wholesale removal of control that happens when a litigation friend is appointed. For me this raises concerns, especially when (as I believe is the case in this hearing) the litigation friend has been appointed on the basis of an interim decision that P lacks capacity to conduct proceedings without there having been a full consideration of this issue.

CAPACITY

I (Celia) have seen articulate, eloquent, intelligent and assertive Ps (like Ms P) in the Court of Protection many times and blogged about them here and here. (See also the blogs by Clare Fuller (here), David Thornicroft (here) and Jenny Kitzinger (here)).

“Some people subject to best interests decision-making in the Court of Protection are a long way from the popular imaginings of the typical “incapacitous person” [and] some can present very clear and compelling statements about the choices they wish to make for themselves.” (Jenny Kitzinger)

For some observers, this was revelatory:

Kris Price

As a trainee capacity assessor (without, as yet, having started training) I found this hearing a real eye-opener. My knowledge about lack of capacity has been gained in the context of dementia, rather than mental health issues. Watching this hearing made me realise that I had preconceived ideas about how someone who lacks capacity to make a decision would present in the court. I’m ashamed to say that I had stereotyped views that they’d be obviously incoherent or a complete emotional wreck. Yet there had been four different assessments of Ms P’s capacity to make a decision about surgery and they had all – including the independent one – concluded that she did not have the mental capacity to make this decision. That was a real epiphany moment – to realise that someone can be articulate, coherent, engaged with court procedures, and still lack the capacity to make decisions about her own body.

Jacqui Graves

I was really surprised that Ms P was not only present at the hearing but was able to speak for herself and not through a legal representative. She was amazingly articulate in expressing her understanding of her situation.

Celia Kitzinger

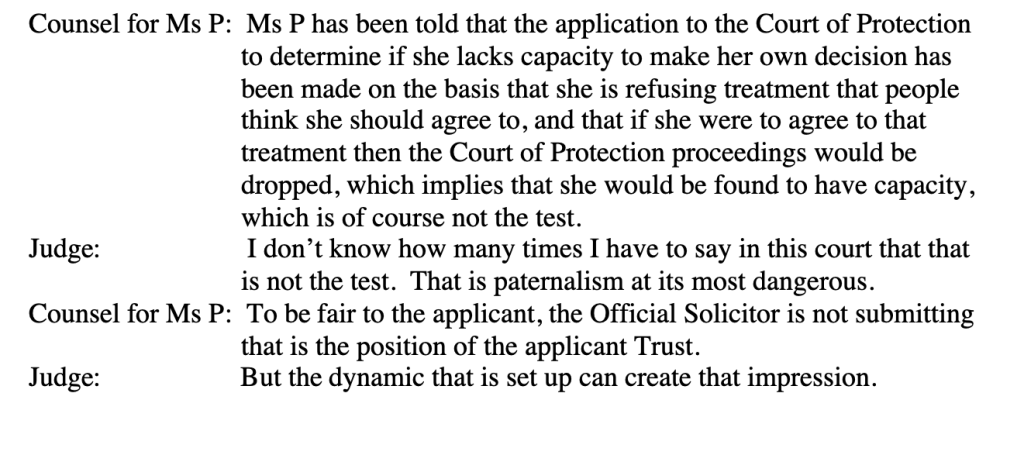

There was concern from some observers that Ms P’s capacity had been called into question because she was making an “unwise” decision to refuse medical treatment. This impression was reinforced by the following exchange:

And that was, indeed, the impression created for many observers – along with a sense that the Trust had not provided Ms P with sufficient information about her treatment options.

Jacqui Graves

Ms P was not challenging her diagnosis, but was challenging the assessments that she lacked capacity to make treatment decisions, just because she was going against medical recommendations. Article 8, the right to private and family life, home and correspondence is the Article protecting our autonomy: anyone with decision-making capacity can refuse treatment. It was clear to me that Ms P felt she hadn’t been given sufficient information about her treatment options to make an informed choice and therefore had refused treatment on that basis. She wants to know not only the full range of treatment options available to her now but also the likely impact of those treatment options on her quality of life. This seems completely reasonable to me and what I would want for myself or my family and friends if I was faced with a similar decision.

Sophie Jones

Ms P was eloquent and appeared to be educated around the topic of capacity and her rights to privacy. The most interesting point I felt was made by Ms P and Mr Justice Hayden, which is (in short) whether Ms P’s capacity is being determined/judged by her refusal to accept the recommended treatment, rather than her ability to make the actual decision for herself.

I find that this can indeed happen in practice, and at times I have felt the (unintentional) judgment of professional opinions being imposed on clients. We must always remember that our clients are allowed to make unwise decisions, as we all do through life. I often reflect back on the Mental Capacity Act 2005 and ask myself “Is the client making this decision for themselves? Have I given them all the information in an accessible manner, for them to make their own choices? If the client appears unable to make the decision, how and why will this be assessed”.

Ms P alluded to the Trust not engaging in discussions with her around treatment options, and gave an example of trying to discuss alternatives she had sourced, and getting no response back. If this is true, then I am not surprised she has declined treatment options to date. Additionally, Ms P appears to be in conflict with the NHS Trust surrounding the timeline of events and delays which may have impacted her treatment options (which Mr Justice Hayden explained was a matter for another court). Ms P stated that due to the Trust deeming her to not have capacity, she was unable to explore legal aid for litigation on the matter. From this point and as a Health Professional, my thoughts go to the fact that we are held by a duty of care to our clients. I found it sad that Ms P appeared to be hinting towards a conspiracy between those assessing her capacity and the Trust. I felt that this issue was impacting her ability to move forward with her current situation and how the professionals involved can improve her quality of life.

Katharine Shipley

It seems likely that the only reason Ms P’s capacity has been called into question at all is because of the gravity of the decision in hand and the fact that her decision to refuse medical treatment has been considered to be unwise. The right to make unwise decisions is one of the central principles of the Mental Capacity Act. It is difficult to speculate about this in this case, without more information about the capacity assessments that have taken place, and indeed the outcome of a new independent assessment that has been commissioned. It was disheartening to hear that Ms P felt that her medical team had not considered all treatment options and that precious time had been lost, resulting in fewer options now being available to her.

There was reference to a previous suggestion from her medical team that if Ms P engaged with the treatment process, the application to the Court of Protection would not be made. Judge Hayden was unimpressed, remarking that this was not the test for capacity and reflected “paternalism at its most dangerous”.

THE JUDGE’S COMMUNICATION SKILLS

There was unanimous approbation for Mr Justice Hayden’s communication skills from all the observers.

Sophie Jones

Overall, I felt that Mr Justice Hayden handled this hearing with exceptional communication skills, ensuring that P was listened to throughout, whilst also asserting himself appropriately when she was not wishing to be “pressed” any further.

Jacqui Graves

It felt quite relaxed and Judge Hayden came across as very warm and very human. I was expecting something much more formal, clouded with lots of legal language, that would make it inaccessible to me. The Judge was very respectful towards P and reassured her that her views were important to him, which in turn reassured me that she was not just being dismissed.

Sophie Keegan

I was surprised by the fluidity of the hearing and by the range of what was discussed. I had presumed the hearing would focus on the issue of capacity in relation to the medical procedure involved and that would be it– but it became obvious that numerous other issues needed to be addressed and both the Judge and the advocates moved flexibly between issues, and addressed them fully when they arose.

There was extensive interaction between the Judge and Ms P herself. The Judge frequently asked questions directly to Ms P and gave her the chance to voice her concerns fully to the court. It was reassuring to see a high level of involvement by P in the case (although I appreciate this may not be possible in all cases). Ms P was very articulate and it felt right that she was able to get her own views across in her own time and in her own words directly to the Judge. The Judge was always sure to state that he took Ps views on the issues seriously. On numerous occasions, he referred counsel for the Official Solicitor to the “valid points” raised by Ms P to him, and sought the Official Solicitor’s response to them.

While this was a case of a very serious and sensitive nature, the Judge through his interaction with Ms P herself created a comforting but efficient environment (with some light-hearted moments along the way) and it was encouraging to feel that Ms P herself was at the heart of this hearing.

Kris Price

I’m a novice observer to this type of hearing and was really surprised by how informal the courtroom seemed and how sensitively everyone approached Ms P. I would not have expected her to have been given as much space and time as she was to address the court and to get her views across. I thought that was excellent. Her views were taken very much into account in formulating the next step.

The judge seemed both sympathetic and empathetic. I was very impressed by him. I thought it was a pity that, because she’d chosen to phone in and not to use the video-platform, she couldn’t see him. I think she missed out by not being able to see him – because you could practically see the cogs of his mind ticking over as he was contemplating the best way forward. He was very engaged, very thoughtful, very concerned to do the right thing. There were some really long pauses where you could see him weighing up the pros and cons of different approaches.

Adam Tanner

In addition to this application, Ms P asked the Court about the processes that Hayden J would have to adhere to in deciding whether or not she had capacity and whether or not she would have to undergo the proposed procedures. Hayden J, not unusually for him, took the time to slowly and succinctly explain the law behind the MCA and how the Court decides whether a person lacks capacity and how it is an issue specific decision, not simply deeming her to lack capacity at all times

Here’s how I (Celia) noted down that exchange:

Adam Tanner

Hayden J has been at the forefront of ensuring that the voice of P is heard in the Court of Protection and that P is included in the hearing about them as much as is feasible (something I also observed in an earlier hearing here). Although Ms P was represented, it was nice to see Hayden J take the time to ensure that she was fully aware of what was going on and that she understood how capacity and best interest decisions are made. Patient-centred discourse has been promoted widely – and this hearing embodied that, with Hayden J taking the lead in ensuring that Ms P’s voice was not only heard but that she fully understood the proceedings.

The next hearing (which some of us hope to attend) will determine whether or not Ms P has capacity to make her own treatment decisions, and – if not – whether the treatment the clinicians recommend is in her best interests.

Celia Kitzinger is co-director (with Gill Loomes-Quinn) of the Open Justice Court of Protection Project. She tweets @kitzingercelia and @OpenJusticeCOP

Jacqui Graves is a nurse and currently the Human Rights Lead at Sue Ryder. She tweets @GravesJacqui

Sophie Jones is Director of Beacon Case Management Ltd, practising as a Case Manager having qualified as an Occupational Therapist in 2010. She tweets @sophiebenko

Sophie Keegan is an LLB Law and French and a BPTC graduate due to start as a Pupil Barrister next year.

Kris Price is a trainee capacity assessor.

Katharine Shipley is a clinical psychologist and Court of Protection Special Visitor. She tweets @KatharineShipl2

Adam Tanner is a PhD researcher in mental capacity law and has contributed previous blogs to this Project (e.g. here). He tweets @AdamrTanner

Photo by Priscilla Du Preez on Unsplash

3 thoughts on “Privacy, Capacity, and the Judge’s Communication Skills”