By Claire Martin, 6th November 2024

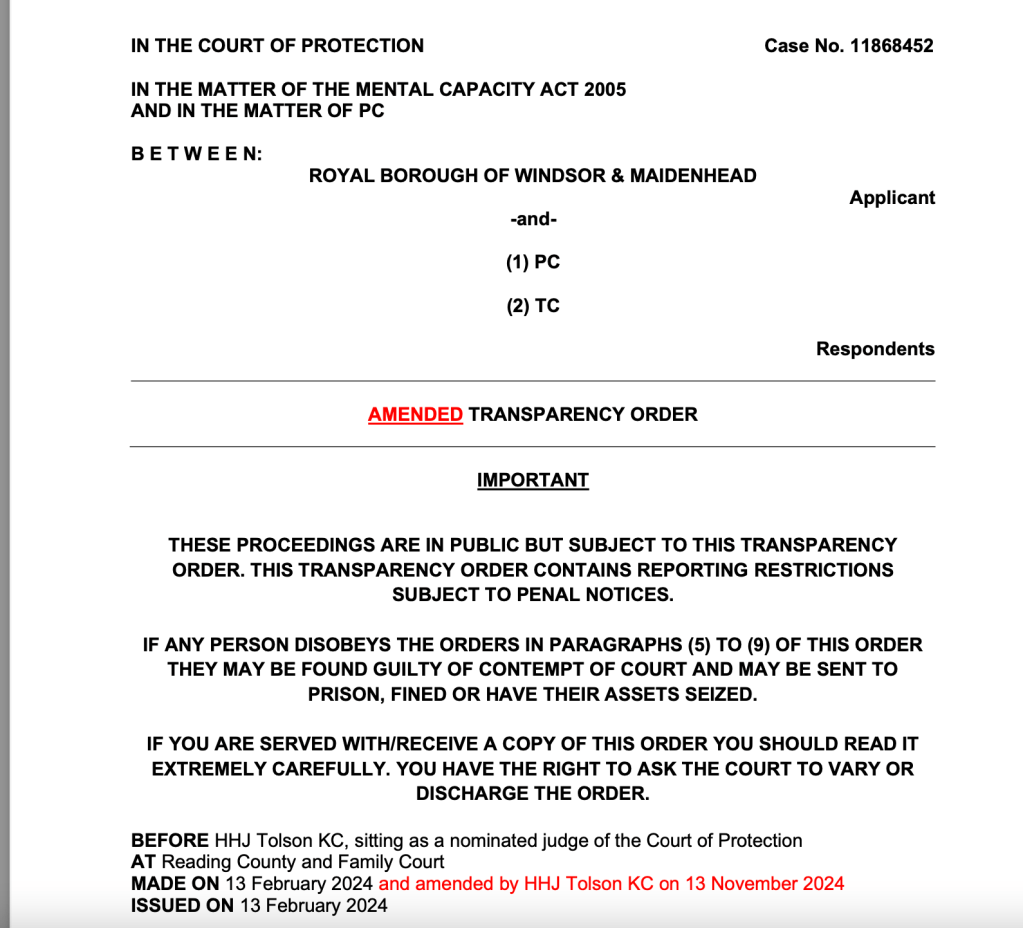

UPDATE: An application to name the local authority (originally prevented by the terms of the Transparency Order) was successful. The local authority is Royal Borough of Windsor and Maidenhead .

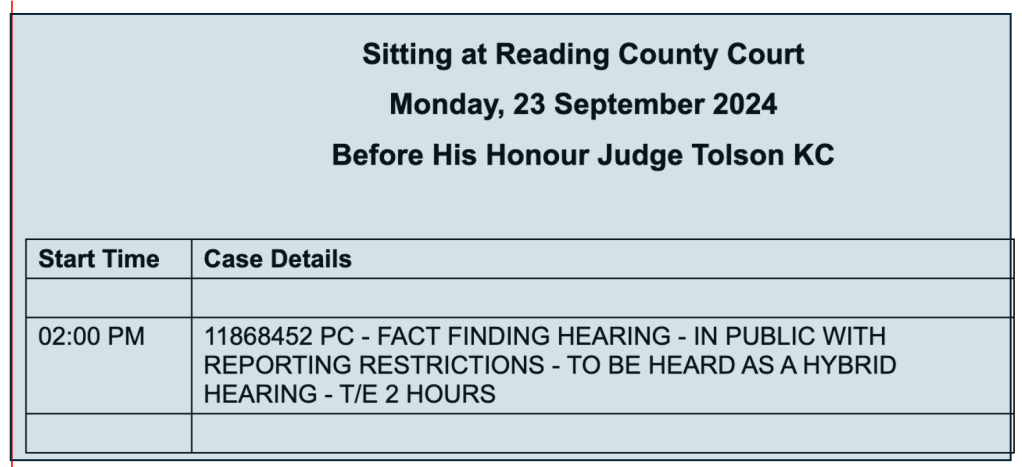

This hearing (COP 11868452), before HHJ Tolson, on 23rd September 2024, at Reading County Court, was listed as a two-hour ‘fact-finding’ hearing (to establish disputed ‘facts’ about the actions of the parties). It turned out to last only thirty-five minutes and was the final hearing in the case.

I think the planned fact-finding hearing was to establish whether P’s cousin, who I will call C, was coercively controlling of P and whether restricting or banning contact was in P’s best interests. It was no longer needed as some facts have now been established in relation to criminal proceedings against C. C pleaded guilty in separate, criminal, court proceedings, to defrauding P of over £30,000 (and the police believe that the final sum is likely to be much higher). He awaits sentencing in November 2024. P has also been working, unpaid, for C in his business for many years, and has sustained injuries and harm (including dehydration and a work-related fracture) whilst working for him.

P was represented by Dr Oliver Lewis (via P’s Litigation Friend – I am not sure if this was an ALR – Accredited Legal Representative but it was stated that the Litigation Friend was not the Official Solicitor) and the Local Authority was represented by Michael Paget. I have not named the Local Authority in this blog post because I think I am forbidden (by the Transparency Order) from doing so. I have addressed this matter at the end of the blog post – see the section below called “Transparency Matters”.

I am going to record what I know of what has happened so far in this long-running case, then describe the process by which HHJ Tolson came to a very quick judgment. I will end by discussing the role of the Court if Protection in ‘oversight’ of people’s care and then mention transparency matters.

What has happened so far?

There have been several hearings in this case already, but no opening summary of the case was provided in court and proceedings moved at pace, so it was quite difficult to follow what was happening. This is contrary to Mr Justice Hayden’s (former vice-president of the Court of Protection) guidance which states: “a small practical suggestion to improve access to the business of the Court when press or other members of the public join a virtual hearing. Whilst the judge and the lawyers will have read the papers and be able to move quickly to engage with the identified issues, those who are present as observers will often find it initially difficult fully to grasp what the case is about. I think it would be helpful, for a variety of reasons, if the applicant’s advocate began the case with a short opening helping to place the identified issues in some context.”

This guidance is reflected in a recent Open Justice Court of Protection Project blog, “Top Tips for Judges”, which includes this as “Tip 14”: “Ensure that the hearing starts with an “opening summary”, detailing the basic facts of the case and the issues before the court. This would also be in line with the advice of the former Vice-President, Mr Justice Hayden (“The Court of Protection and transparency”). Some judges prefer to do this themselves; others ask counsel for the Applicant to do so.”

Unfortunately, due to lack of an opening summary I don’t know what is said to be P’s “impairment of, or a disturbance in the functioning of, the mind or brain” (S2 (i) MCA 2005) such that he is unable to make decisions about his care, contact and finances (the three areas of capacity I think were the subject of best interest decisions for the court in this case). I also don’t know where P is currently living.

What I do know is as follows:

- P is a man who has only one relative, his cousin, C – who has now pleaded guilty to defrauding him

- At the time of the hearing, P didn’t know why his contact with C had been stopped – so he did not know that C had defrauded him of a significant amount of money, only (Oliver Lewis said) that C had ‘done something wrong’.

- In between hearings for P, C’s criminal case has been heard, and he has pleaded guilty to the charges of fraud, meaning that the fact-finding planned for the hearing was not necessary.

- The dispute between parties at this hearing was about whether this should be a final hearing or whether the court should retain some oversight of P’s future contact arrangements with C:

- The Local Authority submitted that they were ‘seeking to conclude proceedings today’

- Counsel for P submitted that ‘the court needs to take time to ascertain what is in P’s best interests (in relation to contact with C)’.

A Quick Judicial Decision

The hearing was quickly into submissions – once it had been established that facts in relation to C’s treatment (in particular coercive control) of P were not necessary.

Counsel for P submitted that the benefit of continuing the litigation would be “…that P would have a Litigation Friend, in the name of Miss XX, and who he trusts, and she can inform court about what his wishes and feelings are. This may be a dynamic situation, but there is a defined piece of work about information gathering from P and [C], because we are IN PROCEEDINGS – it is inappropriate to direct them to go away and do this themselves, then a future final hearing could be vacated by consent at that stage.” [counsel’s emphasis]

The Local Authority was proposing, in their counsel’s words, that ‘the Local Authority can go off and explore that, without the supervision of the court’.

I was interested in how the court would go about making this decision about how much ‘supervision’ the Court of Protection has over P’s life and the relevance of ongoing, ‘dynamic’ decisions. In this case, the Local Authority was very keen to end the court proceedings before P knew about the extent of his cousin’s abuse of their relationship. This would be, then, without the court knowing the impact this information about his cousin’s abuse would have on P, and the nature of ongoing contact between them. In my experience of observing Court of Protection hearings (around 60 since 2020) this seemed precipitous. I have generally observed judges ensuring that the court is furnished with a clear contact plan and that it is in place and working (when contact with an abusive relative is proven) before proceedings are ended.

At this hearing there was no discussion of P’s wishes and feelings in relation to C, save for his counsel mentioning that ‘all we know about P’s wishes and feelings is that he’s OK with supervised contact’. This, of course, is before he knows about the fraud.

On the day of the hearing, the Local Authority was reported (by Oliver Lewis, acting for P) to have changed the details on the supervised contact plan (from monthly to weekly) without explanation. “In my submission, the court should look at a well thought through options appraisal. […] the Local Authority needs to discuss plans with [C], then… he may say ‘I don’t want contact’. So, it would raise P’s expectations [to have a weekly contact plan put in place]. So further work needs to go on. The court needs to take the time to ascertain what is in P’s best interests – whether monthly or weekly – but further work needs to go on. This hearing can’t be a final hearing, it can be a fact-finding hearing. It can find facts and do more work around what is in P’s best interests with regards to contact.” (Counsel for P)

After counsel for both parties had made their opening statements the judge intimated his intent straight away: “Yes hmmm, I’m not sure about that Mr Lewis …. these hearings continuing after today. I am not sure what purpose that would be. Circumstances could change over time …. I can’t see the merit in justifying the proceedings, at significant expensive as they are, continuing in those circumstances.”

It felt to me very much that counsel for the Local Authority wanted to hurry the judge and the proceedings to an end: “There’s going to be a decision to say no unsupervised contact with the caveat. It doesn’t warrant the supervision of the court”. But counsel for P pointed out the risks of curtailing the court proceedings: “Your Honour they’re not agreed [the contact arrangements] because it says [outlined what draft order said about contact] …. There aren’t any supervised contact arrangements RIGHT NOW, so in any event, even if there are, he {P} should be prohibited [from directly contacting his cousin] because the arrangements should be organised by someone other than P. In no circumstances should P be allowed to contact [C] directly. [Counsel for P, his emphasis]

In response to this submission, the judge simply directed amendments to the draft order to reflect that others should arrange supervised contact for P with C.

HHJ Tolson then gave what he described as his ‘short judgment’ (which I reproduce here, as far as my contemporaneous typed notes could capture his speech, so there are likely to be gaps and possible inaccuracies):

“I think these proceedings should come to an end today. They are very longstanding and at considerable public expense. We have sought to engage the cause of the problem (P’s cousin) over a long time and have failed. This has demonstrated that a relationship between P and [C] is manifestly not in his best interests, save potentially in one limited respect. That the two men have been close is obvious from the papers, but what has happened is that charges of fraud brought by the CPS have been subject of pleas of guilty by him. He has defrauded P at least by £33,000 and the police view is [likely] more than that. Other concerns …. Did it involve a form of modern slavery? P was working unpaid in [C’s] [nature of business] business? Was the state of P’s unhygienic cluttered accommodation down to [C’s] actions? Were the conditions under which P worked for [C] such that he was injured out of [C’s] negligence? All of the above arguably demonstrated that the relationship could only be styled as one of coercive and controlling behaviour, so extensive as to characterise the entire relationship. The Local Authority and P’s Litigation Friend now agree that the court should issue an injunction against [C], preventing all contact save one limited respect. What they do not agree on is whether proceedings should end today or whether further work should be done to better define circumstances under which P may spend time with [C] in future. That the injunction should be issued is in my view clear. It is equally clear is there should be a declaration that it is in P’s best interests that he should not have any unsupervised contact with [C]. But as I have said in the past the two men have been close. P lacks capacity, but that does not mean his wishes and feelings are not significant. Suppose it is the case that in future he wishes to spend time with [C] and that [C] is a) at liberty and b) wishes to spend time with P, then [this can be arranged]. My difficulty with continuing proceedings is that it will vary over time … [P’s cousin is] due to be sentenced in November … will he be in prison? ….{missed} [there are] questions not answerable at this and future hearings. The right way to go is to give the Local Authority [permission] to organise supervised contact if it feels it is right to do so, and is (a) in line with P’s wishes, and (b) if [C] consents. Exceptions should say [amendment to the court order such that the Local Authority must organise the contact]. This is a fact-finding hearing, there is no need to make fixed decisions … Findings should record the convictions of fraud, the Local Authority does not pursue any other findings. I do think proceedings should conclude today. Right, that concludes the judgment.”

And that was that – a thirty-five-minute hearing.

Court of Protection ‘oversight’ or ‘micromanagement’?

This hearing led me to wonder whether there is any guidance about how much supervision or oversight is the ‘right’ amount? When should public bodies, in this Local Authority’s words, ‘go off and explore …. without the supervision of the court’? The court can’t oversee ALL best interest decisions. Which ones should it oversee? Which ones does it oversee and what is that based on?

In a recent Court of Appeal judgment (upholding the judgment of Mr Justice Poole in the Re: Covert Medication: Residence case) Lord Peter Jackson (who wrote the judgment with which the other two judges agreed) addressed the fact that the Court of Protection is not a ‘supervisory’ court:

… the Court of Protection exists to make decisions about whether a particular decision or action is in the best interests of the individual. It is not a supervisory court, as confirmed by Baroness Hale, giving the judgment of the Supreme Court in N v ACCG [2017] UKSC 22, [2017] AC 549 at [24], in a passage referred to by the judge: “…the jurisdiction of the Court of Protection (and for that matter the inherent jurisdiction of the High Court relating to people who lack capacity) is limited to decisions that a person is unable to take for himself. It is not to be equated with the jurisdiction of family courts under the Children Act 1989, to take children away from their families and place them in the care of a local authority, which then acquires parental responsibility for, and numerous statutory duties towards, those children. There is no such thing as a care order in respect of a person of 18 or over. Nor is the jurisdiction to be equated with the wardship jurisdiction of the High Court. Both may have their historical roots in the ancient powers of the Crown as parens patriae over people who were then termed infants, idiots and the insane. But the Court of Protection does not become the guardian of an adult who lacks capacity, and the adult does not become the ward of the court.”

§90 in Re A(Covert Medication: Residence) [2024] EWCA Civ 572

HHJ Tolson, in this case, did think the court had discharged its duty to ‘make decisions about whether a particular decision or action is in the best interests of the individual’. The best interests decision, for P, was that supervised contact could be arranged with C (if both P and C agreed), and that others must make the arrangements. He referenced, a few times, how long and costly the court case had become.

So, why continue to have ‘supervisory’ oversight, when a decision had been made, and public bodies enact best interests decisions for people day in, day out, without the Court of Protection’s involvement?

I don’t know the answer to that question. All I know is that I have observed other cases in the Court of Protection where lengthier monitoring, supervision, oversight or what I have heard some public bodies call ‘micromanagement’ (see this blog) happens routinely. Why not this one?

The case referenced in the Court of Appeal judgment above (and we have blogged about many times) has been in the Court of Protection since 2018. At a recent hearing (see blogs here and here) it was ordered that the case must come back before the court in another twelve months, when the Deprivation of Liberty authorisation is due for review. So that will be eight years in proceedings. Whilst this could be ‘on the papers’ rather than in a court hearing (as long as there have been no changes or difficulties) the Court of Protection retains oversight.

The decision for P in this case, though, wasn’t about Deprivation of Liberty (although I suspect he was deprived of his liberty as he would be unlikely to be deemed capacitous to decide where to live, go out etc., given the description of his level of exploitation from C). So, I am guessing that a Deprivation of Liberty authorisation did also apply to this case.

Eleanor Tallon, addresses ‘micromanagement’ in this blog about the Court of Protection streamlined process (known as Re: X) which is ‘designed for non-contentious cases which allow for judicial review without an oral hearing (or ‘on the papers’):

“To some, it could be seen that the court is tasked with micro-management of a care plan, and there may be some debate as to whether this is best use of court time, as it should be the responsibility of the provider and the commissioning body to ensure that the care plan meets the legal and statutory requirements around care standards and human rights.

But in practice, support plans may fall short of this, and often it is these types of cases that come to the attention of the court for further scrutiny.”

The blog continues:

“I was reassured that the Judge in Cassie’s case was intent upon seeking specific evidence to address the discrepancies between the care planning and the actual implementation. In effect, it was highlighted that a support plan may sound wonderful, but the real question is whether the plan is being carried out effectively.

The proof is in the pudding.”

In this case, though, as Oliver Lewis submitted, “[t]here aren’t any supervised contact arrangements RIGHT NOW”. So, the court wasn’t authorising a plan that had been formulated. And indeed, it did not know whether P, or indeed his cousin, C, wanted to have continued contact with each other. The ingredients for the pudding hadn’t yet been selected.

Another long-running case is that of Tony Hickmott, who was detained in a psychiatric hospital for many years. His parents made an application to the Court of Protection in 2019 and the judge ruled that Tony must be discharged from hospital. He has been living in a renovated house with care since October 2022. However, this is not going as well as hoped and recently the case has come before the court again (blogged here). One issue is the role of the court and whether ongoing involvement is warranted. In the blog, Amanda Hill writes:

“I found the discussion around the role of the Court of Protection interesting. Initially the court had been involved to order Tony’s discharge from hospital. Now the parents want the court to stay involved to ensure that Tony is receiving appropriate care. Although counsel for the parents [also Oliver Lewis]stated that the court’s role isn’t to “micromanage”, it seemed to me that without the Court’s continuing involvement, Tony’s parents fear that there is no mechanism for ensuring improvements are made to Tony’s care and that he receives good ongoing care.

The judge seemed to accept in the hearing that the court will continue to be involved on an ongoing basis. She said “…you are right that the main purpose was achieved. Tony is now living in the community. The court will probably be involved in the rest of Tony’s life for the Deprivation of Liberty authorization. So, the dispute between the parties is about the nature of that involvement”.”

One difference between Tony Hickmott and P in this case, of course, is that Tony has loving parents who advocate strongly for the court’s assistance in ensuring his care is good enough. P in this case has no other relative, other than his exploitative cousin, C. Could it be that when faced with relatives who are desperately trying to secure adequate care for their relatives, judges are more likely to agree to the court’s ongoing involvement? I don’t know – and I can’t find guidance on what criteria apply to oversight of the implementation of court orders. Is there any?

In this case, the judge’s decision felt cursory and without a full explanation of why the contact plans for P shouldn’t be scrutinised by the court.

As well as cost, court hearings are often unsettling for P, and/or their relatives and many people do not want them to continue. In the case of Re: A, that is certainly the situation for A and her mother who experience the court, and services involved on behalf of the state, as intrusive and unwelcome. Although the substantive hearings for that case are at an end, the possible developments in A’s case are also dynamic and, as HHJ Tolson warned in this hearing ‘[c]ircumstances could change over time’, so they could for A. I feel uncertain about why, in this case, the potential for change over time weighs less heavily in favour of the COP remaining involved, than for A in her case.

From what I heard in this hearing, P is a very vulnerable man, who has lived under the coercive control of his cousin for many years, seemingly believing he is working for him, yet in reality having been subject to what seems to be a form of modern slavery. He was not paid for his labour. He also suffered physical harm as a result of that labour. If P is under a Deprivation of Liberty authorisation he will have an RPR (Relevant Person’s Representative). He has no one, other than statutory services, to look out for him.

Transparency Matters

The hearing was listed like this:

It correctly lists it as a public hearing, which is as it should be, and tells us it is ‘hybrid’, meaning some of the parties are in the physical courtroom and others attending via a remote link.

The court clerk had helpfully sent the Transparency Order about two and half hours before the start of the hearing (and told me I would receive the link from the court directly). I received the link for the hearing ten minutes before it was due to start, so I was starting to get anxious I wouldn’t receive it.

The importance of receiving the Transparency Order well before the hearing is that it enables us to check the subject matter of the injunction – what we can and cannot report. Sometimes public bodies are included in the injunction and (although there are sometimes very good reasons to anonymise public bodies – for example if it might put P at risk or make their identification inevitable) the default position is that public bodies should always be named in public hearings. They are accountable to us, the public, paid for by our taxes.

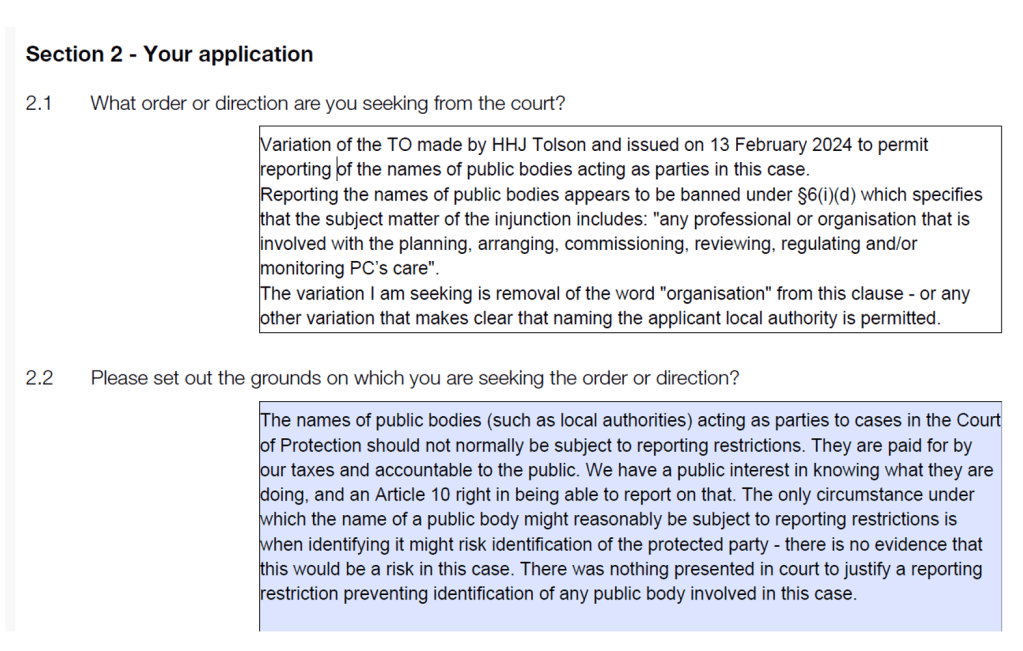

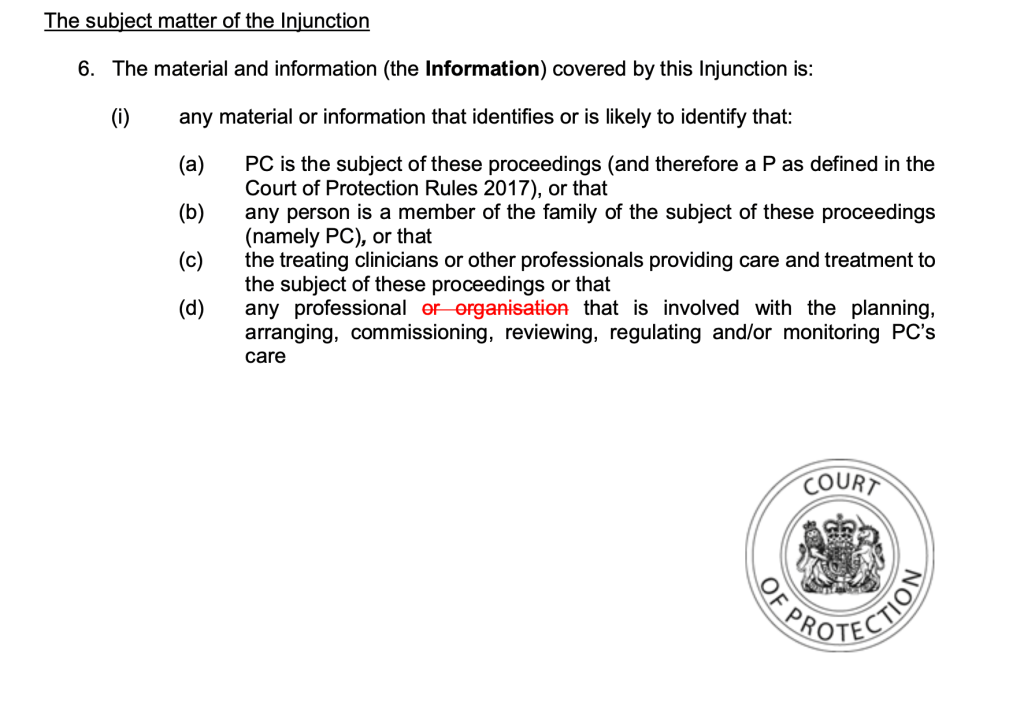

On this occasion there did appear to be an injunction against naming the public bodies involved in the case. This is what it said:

The subject matter of the Injunction

6. The material and information (the Information) covered by this Injunction is:

(i) any material or information that identifies or is likely to identify that:

[…]

(d) any professional or organisation that is involved with the planning,

arranging, commissioning, reviewing, regulating and/or monitoring PC’s

care

I took the opportunity to email the staff member back asking her to raise the TO with the judge:

Dear XX

Please could this be brought to the attention of HHJ Tolson. Thank you.

Dear HHJ Tolson

I am a public observer and core team member of the Open Justice Court of Protection project. I am hoping to observe a hearing before you this afternoon.

I would like to clarify the TO for the case COP 11868452.

It is 6(i)(d) that I wish to clarify. I read this as meaning that I CAN name a provider public body (such as a Local Authority or an NHS Trust) in any reporting about the public hearing.

If I have misunderstood the wording of the TO and the “professional(s) and organisation(s)” included in “planning, arranging, commissioning, reviewing, regulating and/or monitoring” P’s care are indeed public bodies involved in the provision and delivery of care, I would like to request a variation of the TO to enable me to name any public body that is involved in the case. I understand that there must be careful consideration and balancing of Article 8 and Article 10 rights in a decision such as this. It is unusual for us to be required to conceal the identity of public bodies – paid for by our taxes and publicly accountable for their actions.

Many thanks for your consideration of this matter and thank you for your support of open justice.

Yours Sincerely

Dr Claire Martin

Public Observer and Core Team Member of Open Justice Court of Protection

HHJ Tolson didn’t refer to my query in the hearing (which judges often do, because the query relates directly to the transparency of the case, and it is far more efficient than needing to address the issue after a hearing has ended).

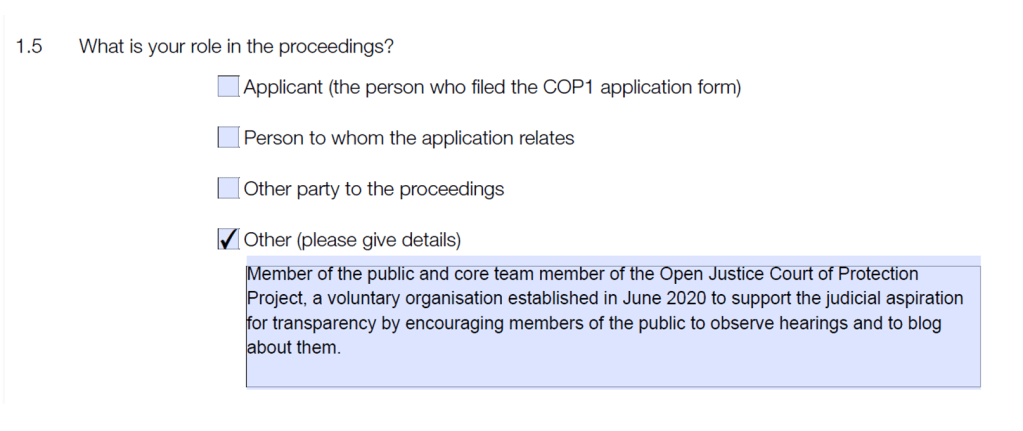

I didn’t receive a reply, so I sent a formal application via a COP9 form on 20th October 2024 requesting that the Transparency Order is varied to enable the naming of the public bodies involved in P’s care. This is what I said:

Update: On 15th November 2024 I received an email from the court attaching an amended Transparency Order. It was the previous Order, amended in red. Here’s the front page.

And paragraph 6 had been amended as I requested. Here’s how it looks now.

Success! Ir would be even better if the court could get it right first time in future.

Claire Martin is a Consultant Clinical Psychologist, Cumbria, Northumberland, Tyne and Wear NHS Foundation Trust, Older People’s Clinical Psychology Department, Gateshead. She is a member of the core team of the Open Justice Court of Protection Project and has published dozens of blog posts for the Project about hearings she’s observed (e.g. here and here). She is on X as @DocCMartin and on BlueSky as @doccmartin.bsky.social

One thought on “How much court ‘oversight’ should there be in long-running COP cases? ”