Jenny Kitzinger, 15th November 2024

It felt quite lonely and empty in Court 33 in the Royal Courts of Justice when I went (in person) on 14th October 2024.

The case (COP 14234849) concerned a man in his early 60s who’d suffered a cardiac arrest in 2017, been resuscitated, and then remained in a prolonged disorder of consciousness [PDoC] ever since. He had no visitors, and at the time of the court application no family or friends had been identified and very little was known about his life before his injury, except that he had been very socially isolated.

The central issue to be determined by the court was whether or not it was in his best interests to continue clinically-assisted nutrition and hydration – although it soon became apparent there were also some more general issues at stake.

Usually, when I go in person to a hearing about PDoC there are family present – indeed, historically my reason for going along to a courtroom (as opposed to, more recently, just attending online) has been precisely to support the patient’s relatives in court. I’ve done this as an offshoot of my research in the Coma & Disorders of Consciousness Research Centre: we often have people coming to us for help when they have concerns about their relative’s care, particularly when they are frustrated by failures or delays in addressing best interests around life-sustaining treatment.

Going to this hearing made me realise that of multiple PDoC court hearings that I’ve attended, I’ve only twice before been at hearings without family or friends present. Once this was because the patient’s brother was too distressed to go (although he’d submitted a detailed statement) and asked me to go along instead; another time, the family were expecting a simple ‘directions hearing’ and were happy for me to simply report back to them – but the judge decided to make a final ruling because the evidence was already so compelling. (The man in question had already been a permanent vegetative state for over 20 years and his parents were clear that he’d not have wanted that: see Kitzinger J & Kitzinger C. (2017) Why futile and unwanted treatment continues for some PVS patients (and what to do about it) International Journal of Mental Health and Capacity Law. pp129-143.)

So, being in court this time felt very different. There was nobody who knew the patient and could try to articulate his possible views – no family members who might disagree with each other about what those might have been. There was nobody to miss or mourn him, and no sense of an individual who was part of a family or community.

There were almost no resources for the court to work with in an effort to ensure that the protected party’s voice was heard as much as possible, no material to ensure that his wishes and values were ‘present’ in the court. Extensive efforts had been made by the clinicians involved. The Official Solicitor, who’d been able to deploy third party disclosure orders, had also tried to gather information. But it had proved impossible to find anything that might give the court insight into this patient’s wishes, values, beliefs and feelings that might be relevant to his current situation.

This lacuna not only impacted on the atmosphere and process of the hearing, it also, of course, created challenges for making a best interests decision and raised questions of principle about how to assess the patient’s best interests. It is that which makes this case so particularly interesting.

It also accounted for the presence of a journalist sitting on the press benches. The majority of court hearings about adults in PDoC do not receive media coverage. What attention they do get may be random (a journalist just happens to be in court on the day), unless the press are informed in advance that there may be something interesting about a particular case that makes it of more general public or legal interest.

The hearing

This case was heard before Mrs Justice Theis, the vice president of the Court of Protection.

The application was brought by the NHS North Central London Integrated Care Board [ICB] responsible for funding the patient’s care – represented by Claire Watson KC. The application was for the court to determine whether it was in this patient’s best interests to continue to receive clinically assisted nutrition and hydration (CANH). The court was also being invited to produce some general guidance about how to handle best interests when there is very limited evidence about a patient’s wishes, feelings, belief and values because of the absence of friends and family.

The other parties were the Royal Hospital for Neuro-Disability (where the patient resides) – represented by Ms Katie Scott, KC and the protected party, known as ‘XR’, represented (via his litigation friend, the Official Solicitor) by Mr Michael Horne KC.

The patient had suffered a severe hypoxic ischaemic brain injury in 2017 (then in his 50s) and had been an inpatient at the Royal Hospital for Neuro-Disability (“the RHN”) since Spring 2018.

The treating team and second opinion experts agree that he is in a prolonged disorder of consciousness [PDoC], with no prospect of any recovery, and at the lowest end of the spectrum (what historically would have been labelled a Permanent Vegetative State). His treating clinician, Dr A, felt that in the absence of knowledge about XR’s wishes, the decision about clinically-assisted nutrition and hydration was ‘finely balanced’.

Two second-opinion experts gave oral evidence in court: Professor Wade, Consultant in Neurological Rehabilitation and Dr Hanrahan, Consultant in Neuro-rehabilitation. Both took the position that it was clearly not in XR’s best interests to continue with CANH.

Professor Wade testified first – and he was cross questioned about how he’d made his diagnosis, and in particular why he thought it was possible that, even in his highly compromised state, XR might experience some form of pain (‘in the moment’, without the ability to anticipate, explain or remember it). He was also asked in what way XR’s condition or treatment might be considered ‘burdensome’ if he, in fact, could not experience that burden, and asked about XR’s day-to-day life and his future. It was clear that XR’s future was one of inevitable deterioration, but he was clinically stable. If life-sustaining treatment continues, he might die soon anyway from a one-off incident, or alternatively he might live on for another 10, or even 20 years.

Dr Hanrahan gave evidence next. His testimony and cross-questioning covered a similar range of issues. Generally, this presented a very consistent view of XR’s diagnosis and prognosis but it was clear that Dr Hanrahan had a different view on the potential for pain – judging it inconceivable that any pain could be experienced given the severity of the brain damage. He agreed with Professor Wade, though, that it was right to provide treatment ‘as if’ pain might be experienced.

There were other questions to both experts, including some that sounded rather critical from the Official Solicitor, asking Professor Wade about why he thought it was a straightforward best interests decision to discontinue CANH for this patient and on what basis he had speculated about what XR’s wishes might have been. Counsel for the Official Solicitor, Mr Horne, drew attention to, and problematised, inferences about what XR might want by reference to survey data about what ‘most people’ would want in this situation. He also challenged a postulation that a man who lived in such an isolated way probably valued his privacy and would have found his current situation of total dependence in a hospital anathema to the way he lived his life. Mr Horne pointed out that further rigorous investigation that the Official Solicitor had been able to do (e.g. using powers to get information disclosed from other organisations with which XR had had contact during his lifetime) had revealed more information than others had been able to obtain, and that one could not assume that how someone lived was necessarily though choice.

The closing statements from all three parties concluded that it was not in XR’s best interests for CANH to be continued.

Each closing statement also argued for more judicial guidance for cases such as XR’s, with the Official Solicitor concluding that, without the appointment of the Official Solicitor and bringing these cases to court, clinicians risk making unjustifiable inferences and also: “marking their own homework and being judges in their own courts”. It was not clear to me from the hearing what general principles were being drawn from this case and how that might inform judicial guidance about cases ‘like XR’ in future, and I didn’t feel I’d heard the evidence around that unpacked in court (although there was much more information in the Position Statements which I received later, after they’d been redacted).

The judgment

The judgment has now been handed down. It’s available here: NHS North Central London Integrated Care Board v Royal Hospital for Neuro-Disability & Anor [2024] EWCOP 66 (T3) (14 November 2024)

Is CANH in XR’s best interests?

A far as the key question about CANH is concerned, the judgment is straightforward. Mrs Justice Theis rules that it is not in XR’s best interests to continue to be given CANH.

Delays – again!

The judge is highly critical of delays in considering this patient’s best interests. She quotes the Official Solicitor’s statement that “even in a specialist facility such as the RHN”, XR remained “drifting in a vacuum of ineffective best interests decision making for a number of years.” Such delays, the judgment emphasises, are ‘wholly unacceptable and contrary to the patient’s best interests”. The judgment also spells out an important message for Integrated Care Boards. Annual reviews of the care the ICB commissions:

“.. should include active consideration by the ICB at each review to be vigilant that the care package includes an effective system being in place for best interest decisions to be made in these difficult cases so that drift and delay is avoided. The ICB should not just be a bystander at these reviews.”

The issue of CANH being given by default without any best interests assessment is a depressingly familiar point. Judges have been criticising this in case after case for many years now, and it’s something I’ve written about in several articles (e.g. Kitzinger, J & Kitzinger, C (2016) Causes and Consequences of Delays in Treatment-Withdrawal from PVS Patients: A Case Study of Cumbria NHS Clinical Commissioning Group v Miss S and Ors [2016] EWCOP 32, Journal of Medical Ethics, 43:459-468.)

Ironically, in some ways the recent cases exposing delays in relation to patients at the RHN may be partly because this hospital has made efforts to get systems in place, and review patients’ best interests – following major criticism of how another patient, ‘GU’, was treated by the RHN in a judgment published in 2021 (North West London Clinical Commissioning Group v GU [2021] EWCOP 59.)

While the RHN undoubtedly has more work to do, I am very concerned that some centres with a large number of PDoC patients never seem to have any cases come to court. This leads me to suspect that these centres may not be carrying out best interests reviews of CANH at all, as it seems unlikely that all of their patients have clear-cut best interests, where there is no dispute about CANH or where the decision is never finely balanced.

General guidance?

The judge declined to produce the general guidance requested in the application from the ICB. But it was interesting to see though that a lot seems to have happened by way of evidence-gathering, reflection and discussion around the general points since the hearing. Not least, some parties may have changed their positions or arguments, with consultation happening with those involved in producing professional guidelines about PDoC for the Royal College of Physicians and the RHN position moving away from requesting judicial guidance in these cases.

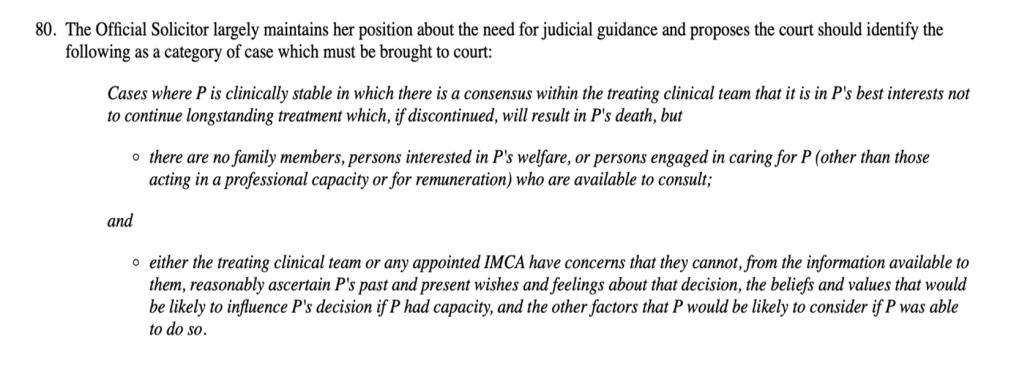

The Official Solicitor, however, had reportedly remained of the opinion that a discrete sub-category of cases where CANH discontinuation is being considered should come to court.

Later, in §84 of the judgement, it is stated that if judicial guidance requires cases ‘such as XR’ to be brought to court the Official Solicitor submits that this will facilitate “a reduction in the pool of patients who are unlawfully receiving continued longstanding life-sustaining treatment by default because of an absence of family or friends to consult”.

It is not obvious how implementation of the suggestion in para 80 could result in facilitating such a reduction in treatment by default for these patients as outlined in para 84. It seems more likely to exacerbate the problem by creating a new barrier (the need for court application) to withdrawal of treatment from Ps without family and friends.

Clearly, a “reduction in the pool of patients who are unlawfully receiving continued longstanding life-sustaining treatment by default because of an absence of family or friends to consult” could only be achieved if the category of cases which “must” be brought to court were composed not only of those cases where there is a consensus within the treating clinical team that it is in Ps best interests not to continue life-sustaining treatment (as suggested in para 80), but also those cases in which the treating clinical team have adopted the position that (since family and friends are not available to argue a contrary position), treatment should simply continue indefinitely.

The reality on the ground is that clinically stable PDoC patients are routinely given CANH and other treatments by default, often for decades. Our research shows that withdrawal of treatment that is not in a patient’s best interests often comes about only with the intervention of family members to advocate for the patient, and that without families to raise concerns about ongoing treatment, it is likely to continue by default. (Withdrawing artificial nutrition and hydration from minimally conscious and vegetative patients: family perspectives).

There is a great deal more in the judgment to analyse, including reflections on how Independent Mental Capacity Advocates might investigate when patients are unable to communicate values, wishes, feelings and beliefs themselves and have no family or friends. Finally, this judgment could also usefully be analysed in relation to the question of when treatments are ‘on offer’ or not, and when a decision is a ‘best interests’ decision at all – a matter that does not seem to have risen to the surface of the arguments made in this case.

Jenny Kitzinger is co-director of the Coma & Disorders of Consciousness Research Centre, and Emeritus Professor at Cardiff University. She has developed an online training course on law and ethics around PDoC and is on X and BlueSky as @JennyKitzinger

Declaration of conflict of interests: Jenny Kitzinger has recently been on a work placement at the Royal Hospital for Neuro-disability but had no involvement in this case and did not observe or write about the hearing as part of her placement activity.

I find the point about avoiding assumptions based on how P lived her or his life compelling. Particularly in our post-pandemic society, isolation and loneliness are endemic – especially among older and/or disabled people (who are likely to form the majority of P’s in COP proceedings). And inferring active choice from their living circumstances strikes me as a risky action. I think this illustrates the complexities involved in advocating for P’s ‘voice’ to be upheld while ensuring one avoids adding insult to the injury of social marginalisation.

LikeLike