By Claire Martin, Laura Eccleston and Jess Wright, 8th December 2024

Claire, a seasoned observer and member of the core team at the Open Justice Court of Protection (OJCOP) Project observed a hearing with two new observers: Laura Eccleston (an Admiral Nurse) and Jess Wright (student nurse). This was their first time observing a Court of Protection hearing. The three of us were in touch during the hearing via WhatsApp. Communicating via WhatsApp provides support for access, answers (if we can!) any questions during the hearing, and enables reflection in real time. It is increasingly a service we’re providing through OJCOP for new observers.

It can be daunting to attend court for the first time on one’s own. Even after locating a hearing to observe, getting the link is not always straightforward. On this occasion we had not received the link quite close to the start time, so Claire emailed the court to enquire further. The clerk was very helpful and told us that the hearing was starting late. But most first-time observers would be reluctant to email the court chasing a link (and of course, it would be better if court communication were such that we were not placed in the position of needing to do that).

The hearing was on CVP (Cloud Video Platform), which is not easy to navigate. For example the first box you encounter on logging on asks whether you want to join by ‘audio+video’ or as ‘an observer’. Well, we are observers, aren’t we? But no, that would be the wrong box to tick – if you do that it means that no one on the court side can hear or see you and you can’t turn on your mic or camera! Sometimes this might not matter, but we’ve found in the past that judges and court staff (unaware of the implications of joining as “an observer”) often ask us to switch on our camera and to confirm that we can see and hear the court, and/or that we’ve received the Transparency Order. On occasion they’ve removed us from the hearing when we’ve not responded (because, if we’ve logged on as “an observer”, we can’t). So, what we advise everyone now is that they click ‘audio+video’ and later click, ‘guest’. All this is even before you are in the hearing, and sometimes before you have received the Transparency Order. (Later in this blog post, Laura reflects on the impact of reading the Transparency Order: it can be very off-putting for everyone, especially first-time observers.)

We were looking for a hearing about an older person, because we all work in older people’s mental health services, however the listings do not give that level of detail about the person at the centre of the case. So it was the listing of this case, as a “Final Hearing” which drew our attention. Final Hearings can be interesting because they are (often) the culmination of all of the evidence and the judge provides a judgment about the decision being made. This is what happened at this hearing.

This is how the listing appeared in Courtserve/Courtel the Friday before the hearing:

In turned out that the hearing was about where P should live and (although it wasn’t clear from the outset) we pieced together the information that P has been living in her current home (which we will call Care Home 1) for seven years. She doesn’t like it there and wants to move. Counsel for P (Bethan Harris, via her Accredited Legal Representative) said that there were ‘not a large number of options’. The ICB (Surrey Heartlands Integrated Care Board, represented by Conrad Hallin, who also represented the Local Authority, Surrey County Council) had put forward one specific option and P herself had proposed another.

This was a final, remote, hearing (COP 14075656) on Monday 25th November 2024, before DJ Nightingale in Guildford to determine where P will live in future.

Transparency Matters

We had some helpful correspondence with the court clerk (noted above) assuring us that the link would arrive in time, and informing us that the start time had been delayed by at least half an hour because the judge was conducting a remote (private) judicial visit with P. We were also sent the Transparency Order, which tells us what we cannot report about the case.

Unfortunately (contrary to guidance from the then-vice-president of the Court of Protection) an opening summary was not provided. We were all totally lost about what was happening. Even though Claire is a seasoned observer in the Court of Protection, she did not know what was happening either, other than that the matter seemed to be about where P should live. P was on the link too, with her sister (who was not a party to proceedings but was invited to address the court).

Here are some WhatsApp exchanges illustrating the lack of understanding about what was happening in the hearing (The green messages are from Claire:

It was only (after the hearing) on receiving the very helpful Position Statement from counsel for P, that we learned what are said to be P’s ‘impairments of the mind or brain’ [s.2(1) MCA 2005] and the history of the case.

The judge did spend several minutes at the start of the hearing addressing the fact that there were three observers and that we were bound by the TO and that:

“The court has the power to exclude persons if it is in the interests of justice to do so, but the purpose of the injunction is to set out if third parties attend … it makes it clear that 3rd parties who attend a hearing such as this … [reading out TO]

Of course, it is important for us as observers to read and understand the TO – but it is also important for open justice for the wider public to understand what is happening in our courts, otherwise justice is not ‘transparent’. The judge, rightly, explained that observers in court are a potential risk to people’s (Article 8 ) rights to privacy. It would perhaps better support the judicial aspiration for transparency if this were to be balanced with acknowledgement of the public’s right to freedom of information (e.g. a summary) to comply with Article 10 rights.

Background

We learned from the Position Statement that P is a woman in her 50s who brought the application (via her ALR) to court in April 2023 under Section 21a of the Mental Capacity Act 2005. She wants to leave Care Home 1, and furthermore Care Home 1 is saying that it can no longer meet P’s needs.

P (we were told in court) has been able to clearly express her views to the court about her care, what is important to her, and where she wants to live. She was on the video-link with her sister, sitting on her bed in her room and, at times, moving about.

P has diabetes (we think Type I) and is understandably concerned about her dietary needs being adequately met. She experienced a diabetic coma in 2005, and lived with her mother until 2017, since which she has lived in Care Home 1.

During these proceedings, P has been assessed by an expert consultant forensic psychiatrist (Dr O’Donovan) who has given P diagnoses of ‘delusional disorder in the context of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and significant health anxiety’. She reported that ‘these mental health conditions have a very significant impact on [P’s] behaviour and level of functioning’. We assume that it is these diagnoses which underpin the determination that P lacks the capacity to make decisions about where she lives and what care she receives. Dr O’Donovan’s view was that P fully understands the court process, can retain the information about the proceedings and communicate her views, but that she is not able to weigh up the necessary information in order to make decisions (for litigation, residence and care needs).

The Position Statement also describes P’s current view about her mental health diagnoses: she declines any and all treatment for her mental health and will not engage with the Community Mental Health Team (CMHT). Dr O’Donovan recommended a home for P that could ‘support adults with chronic and enduring mental health needs’.

Where shall P live?

The ICB (Integrated Care Board – formerly CCG, Clinical Commissioning Group) has proposed one particular placement, which we will call Care Home 2.

Care Home 2 is a specialised community hospital which provides acute and rehabilitation service for people with mental health needs. We learned that it has a ‘full multi-disciplinary team’ comprising doctors, nurses, psychologists, occupational therapists and dieticians. There are ‘step-down’ apartments on site and the aim would be to enable P to move into one of these semi-independent apartments (which have 24/7 support) in time.

P does not like the idea of living in a ‘hospital’ setting and has herself approached a care home (which we will call Care Home 3). This care home is registered for EMI (Elderly Mentally Infirm). P knows the manager there, who supported her when she lived elsewhere. The court was told that P’s mental health needs, were she to move to Care Home 3, would be provided by the Community Mental Health Team. There is no current vacancy at Care Home 3.

It was clear that all parties viewed Care Home 2 as the best place for her. P herself did not agree (but she is represented via her ALR, who makes submissions in what they think are P’s ‘best interests’, which might not – and in this case, did not – accord with P’s own views: see https://www.mentalcapacitylawandpolicy.org.uk/litigation-friend-or-foe/).

Counsel for P: The magnetic factor in this case […] on behalf of the ALR for P is where P’s needs would be best met, and where all P’s needs can be best met. The court has received information about the TYPE of place that Care Home 2 is, and the holistic provision that Care Home 2 makes – a range of professionals, who would be able to meet P’s needs across the board. [Counsel’s emphasis)

Counsel for the ICB and LA: They can fully meet her needs across the board, it has a good CQC rating, a full MDT to help her, a range of activities that she can participate in if she wishes to do so. They have great expertise in helping people with complex medical conditions – diabetes … which she has. There is no formal 1:1 requirement, but it can be provided if necessary. [There are] a lot of advantages to this placement, and although there are not a lot of options, this is a good option. She’s keen to move on from where she is now, this is a good and constructive option. […] The point is that it’s a specialist health placement – specialist in diabetes […] it needs to be carefully managed. There are specialists in the management of diabetes, so it’s not just about dieticians but about diabetes. The intention is for a transition plan to include [P] in considering her dietary requirements with the specialists who are in place. … to make sure she’s on-board with the proposals.

The judge raised several of the concerns that P had spoken to her about: information about the care home, how the transition would be done (she’d previously not had control over her possessions and was keen to ensure this would not happen again), and the environment itself:

Judge: P thinks it will be noisy and she’s a quiet private person

Counsel for the ICB/LA: I can’t see anything that would suggest that this will be a noisy environment, but if you want anything beyond the photographs I will need to ask [the clinical manager from Continuing Health Care].

Social Worker: I can’t add anything to the building or noise – I haven’t visited. [P’s] sister has visited …. I can only see what’s on the brochure.

Judge [to sister]: I don’t want to pressure you – do you have anything to add?

Sister: I was explaining to [P] that the room intended for her is on the end of a block, a semi-detached [block]. When I visited, there was a common room and music, but not noisy. The venue is spacious and there is a garden …. a dining room, quiet areas … different spaces available – a female-only floor where [P] would be, no noise when I was there. Only 14 residents at the time, but it has capacity for more. The staffing ratio is higher … certainly I wasn’t aware – it has a nice homely atmosphere, someone was leaving and celebrating … a positive atmosphere when I spoke to staff.

The judge gave an ex-tempore (oral) judgement, which authorised a move to Care Home 2 – the one that all, including (we were told) all of P’s family, supported. But where P herself does not want to go.

The judge said that one of P’s concerns is that it is a hospital, and that Counsel for the ICB/LA had ‘explained that it’s not a hospital in a formal sense, but a community hospital with an MDT on site’. She ended her judgment by saying: “Care Home 2 offers the best opportunity for [P] to be cared for in a setting for all of her needs to be met holistically”

Reflections

As we listened to the hearing and began to understand that this was a final hearing to make what seemed, by the end, an inevitable judgment , we realised that P as a person had not been discussed at the hearing at all. Save for saying she was a ‘private’ person and that she does not accept any suggestion of mental health difficulties, we didn’t learn much about her. We know nothing about her likes and dislikes and the sort of place that she would prefer (save again for the one care home that she had approached herself, which had a private – not shared, like Care Home 2 – shower, and that P knew the manager).

There was a suggestion that, once she was there, she would see that Care Home 2 was a good choice for her, be more likely to engage with professionals (including mental health professionals) and be able to develop her independence (which she was said to want to do). However, it was concerning to us that there was no evidence presented (orally, in the course of this hearing) to support this contention.

However, as observers, we only see and hear a snapshot of the huge amount of work behind a court hearing, and it is likely that the court had much more of an understanding about these things than we did.

Nevertheless, what we did see, at times, during the hearing was P strongly and visually expressing her views about what she heard.

Laura

I noticed how distressing it was for P as she was getting up and down and throwing her arms open, throughout the hearing, when arguments were being made for different places to those she might have wanted for herself. At the times I noticed this, it was at points where I also felt very confused with what was being said. I also questioned if more had been considered around her physical health conditions rather than the focus being on mental health. One of the questions this made me think of, was how some physical health conditions that people have managed for a long time don’t fit to new routines of different establishments and can made it difficult for people to function as they once did. Often, when people with diabetes are in ‘hospital’ settings, we get people to change lifestyle choices to fit the needs of the hospital, rather than look at what they can do in the community.

At the start of the hearing P had a sheet wrapped around her and was walking around the room. One of the things that I felt was how undignified this was for her, and how everyone could see the pad she was wearing when she was getting into the bed, as she was wearing no pants. Why wasn’t this noticed by the court?

My other reflections are about the process of attending the hearing itself. As a first-time observer, initially when I read through the Transparency Order, I was overwhelmed by the document. The terminology was difficult to follow, in parts. I was also taken aback by the statement about the injunction and how it stated a person may be found guilty of contempt of court and may be sent to prison, fined or have their assets seized. Had I not been supported to access the hearing I would not have gone any further for fear that I would do something wrong. Without support from Claire, I was also unsure about doing the blog as the Transparency Order would have put me off saying the people’s names (barristers and judge) and even identifying the person at the centre of the case as female.

At the beginning of the hearing, the Transparency Order was highlighted by the judge. This was daunting and made me reconsider whether I should be attending.

Following the judge reading this we heard from the barristers. It was difficult to follow who was proposing what and on behalf of whom.

After attending, I felt I was able to recognise in more detail how the COP works. I also considered how difficult it can be for people who are waiting for life-changing decisions to be made. This has made me consider the importance of how we look at the wider picture for people and how we can improve their care. As an Admiral Nurse, I work with family carers of people with dementia and I have experience, as a Community Psychiatric Nurse, of people detained under the Mental Health Act and of Mental Health Tribunals.

My interest in observing the COP hearing was stirred when I attended a talk at work about fluctuating mental capacity in dementia and I learnt about the OJCOP project.

The case left me with the following questions to reflect upon:

The difference between the Mental Health Act and Mental Capacity Act. The COP did make me consider the difference between the MCA and MHA and how different the timescales can be. Things seem to be more regulated and quicker in Mental Health Act detention and tribunals. The difference I have seen is how everyone will be reviewed under the Mental Health Act after a period of time if they have not made an appeal. Rights are provided to people on a regular basis with guidance around this. I can’t say that I have ever come across people having their rights explained around how they can challenge MCA 2005 decisions. I have so many times seen people being told “They’re on a DOLs”, and that’s that. I think that the Mental Capacity Act can be used as a least restrictive option to move someone to a different location. This often makes me wonder, if the Mental Health Act was used, would the person have more rights around being able to challenge.

How do we define what is a least restrictive option? Through the hearing they discussed what was available. When hearing this I considered how this varied between local authorities and how the outcome could be different in different locations.

Submitted evidence: It was unclear through the hearing if services other than mental health services had been consulted. This led me to think about the importance of considering how all aspects of care should be looked at in detail to avoid diagnostic overshadowing.

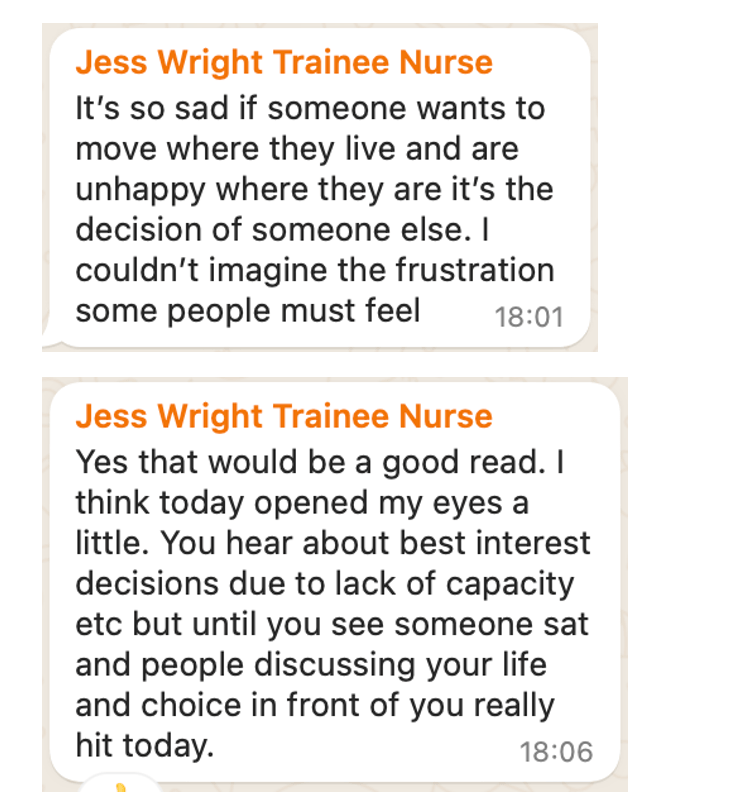

Jess

Jess is a student nurse in the throes of her dissertation. Her immediate, post-hearing reflections are captured powerfully in these WhatsApp messages sent to Claire and Laura in the evening after the hearing was finished.

(The “good read” above is this blog about a 91-year-old woman who wanted to return home to live with her son.)

(In that last message, Jess is referring to feeling upset after the hearing, as she was about to leave work for home. She sent this message after arriving at home the same evening.)

What is clear from Jess’ statements above is how observing a Court of Protection hearing makes (what feel like) cold, legal decisions about people’s lives ‘hit’ you on a personal level. Watching P herself ‘sat and people discussing your life’ helps to develop a level of empathy that reading cases, or working as a professional in your role, don’t necessarily facilitate in the same way.

We hope that P can find a way to feel comfortable in her new home and that, even though others think it’s the best place for her, that her own feelings and views are considered on an ongoing basis in future, whatever they may be.

Claire Martin is a Consultant Clinical Psychologist, Cumbria, Northumberland, Tyne and Wear NHS Foundation Trust, Older People’s Clinical Psychology Department, Gateshead. She is a member of the core team of the Open Justice Court of Protection Project and has published dozens of blog posts for the Project about hearings she’s observed (e.g. here and here). She is on X as @DocCMartin and on BlueSky as @doccmartin.bsky.social

Laura Eccleston is Community Admiral Nurse Lead at Gateshead Health Foundation Trust.

Jess Wright is a student nurse, currently at Gateshead Health NHS Trust.