By Amanda Hill, with Heather Walton and Celia Kitzinger, 10th December 2024

Something significant happened in the Court of Protection on Wednesday 30th October 2024.

Not within the grandeur of the Royal Courts of Justice with a blaze of media attention, but in a regional court: Bournemouth and Poole.

The case (COP14106873) was listed the evening before on Courtel/CourtServe, along with 30 or so other cases for that day. Most people would probably have missed it. It was listed as “Vary the Transparency Order”. I knew about it because I had blogged about the case before.

The decision the judge made at the end of this hearing was that, very unusually, a family member of a living P was allowed to identify herself as such. Although this decision was made on the facts of this individual case, I believe that it is a decision that should have ramifications for other family members who want to tell their Court of Protection story openly. These are stories that deserve to be told but are often banned by Transparency Orders, so the judicial decision that this mother can tell her story should inspire others to consider making applications as well.

Back in August, I (Amanda) wrote a blog about “HW”, who wanted to tell her story about being involved in a Court of Protection (COP) case: She wants to tell her Court of Protection story but will the court allow her?

The Transparency Order covering her daughter’s case, like the Transparency Order in most COP cases, prohibited family members from even saying that they have a relative who is or has been involved in a COP case.

HW (now I can call her Heather) applied to have the Transparency Order varied (changed) so that she could talk about her experience of the Court of Protection openly, in her own name.

Celia Kitzinger, co-director of the Open Justice Court of Protection Project, supported her application and acted as Intervenor in the case.

At a (remote) hearing on Wednesday 30th October 2024 before District Judge Bridger sitting in Bournemouth and Poole Combined Court Centre, the judge approved Heather Walton’s application.

In this blog, I’ll set out the arguments for and against the application from the various parties, and the judge’s decision and the reasoning behind it. Heather, P’s mum, adds her thoughts too, and Celia rounds the blog off with her own comments.

The hearing

At the beginning of the hearing, the judge organised a “batting order”: Heather Walton as the applicant (acting as a litigant in person) was asked to speak first, followed by Celia Kitzinger as the intervenor who supported her application. They were followed by P’s litigation friend the Official Solicitor and P’s father (who were both neutral about the application), and then counsel for the local authority (Wokingham Borough Council) who opposed it.

Applicant: Heather Walton

Heather made a moving and passionate plea to the court to allow her to tell her story as a parent of a protected party so that she will be able to support other families going through the Court of Protection process and help educate social workers and other professionals about what it is like for a family member. Here’s what she said (thank you to Heather for sharing her notes with me):

“Speaking from the heart, I adore my daughter, she gives me so much joy and I’ve met so many amazing people from being her mum. It’s important that the court understands that.

I do not see that varying the Transparency Order, as I’ve asked to, will cause her any possible harm. Of course, if I thought it would, I would not be making this application.

I didn’t choose to be involved in these proceedings – neither did my daughter. That’s true for most families involved in the Court of Protection.

The court has worked to ensure my daughter’s best interests and I’m grateful for its decisions. My daughter is settled and happy.

Although I believe the outcome is a good one for my daughter, the whole process of court involvement is something that I have found stressful and upsetting. It’s not a criminal court, but it’s hard not to feel that you’re being judged and that you’ve done something wrong and to fear the power of the court. I’ve learnt that many families feel that way.

Sir James Mumby said there was “a need for greater transparency in order to improve public understanding of the court process and confidence in the court system.”

This variation will give me the opportunity to help other families going through the process to feel supported and less isolated, something that I know I personally would have really valued during this experience. It will mean I can talk with social workers and those in the legal profession and help them to understand what families’ experiences are.

I’m not asking to name my daughter.

I’m not asking for the release of court documents.

There’s nothing in the Transparency Order at present to prevent me from discussing publicly in the press, online or anywhere else any aspect of my daughter’s private life – or my own life, or other family members. The only thing the Transparency Order prevents me from saying is that we’ve been involved in Court of Protection proceedings – that [Daughter] has been a “Protected Party”.

So the arguments against varying the Transparency Order on the grounds that private information about [my daughter] could “get out” into the public arena are null and void because the Transparency Order does not prevent me from talking about my daughter’s private life. It only prevents me from saying she’s a “Protected Party”.

I haven’t disclosed personal information about my daughter to people inappropriately. I don’t want to. I want to talk about the role of the Court of Protection in family life.

I have a right to free speech, and believe that there is a legitimate public interest in understanding more about Court of Protection proceedings, as well as a real need for training for social work and legal professionals.

There is also a huge need to offer support to families going through the process.

I am willing to give reasonable undertakings to protect my daughter’s privacy. I have always respected my daughter’s privacy and I will continue to do so, whatever the decision today.”

Heather said that she would be willing, if required, to make “undertakings” to the court – for example (as suggested by the Official Solicitor), she would be prepared to say simply that she was a “family member” of the protected party – rather than identifying herself as P’s “mother”. She pointed out, though, that this would negate some of the benefit she thought she could bring to other families, as a parent has a particular role and point of view.

Intervenor: Celia Kitzinger

Celia said that she was appearing on behalf of the Open Justice Court of Protection Project (OJCOP), which had been set up to support the judicial aspiration for transparency.

She emphasized the purpose and effect of a Transparency Order. It is made to protect P’s privacy (not that of other people except in so far as that might impinge upon P) and it’s quite circumscribed in scope. It applies only to information about the protected party in relation to the court proceedings. There is nothing in the Transparency Order to prevent Heather Walton from talking with parents of other children with Down Syndrome or disabilities. The Transparency Order does not prevent her from talking to social workers about how they could provide better support for parents with disabled children. It does not prevent her from sharing her experiences with journalists either. Heather Walton can do all these things without breaching the Transparency Order. The only thing the Transparency Order prevents her from doing is talking about that which relates to the Court of Protection proceedings.

The only new information that the variation Heather was seeking would reveal to the world, is information about the Court of Protection proceedings themselves: that they happened, and what the court experience was like for her. She would be able to say: “I’ve been through it; this is what it’s like”.

The Open Justice Court of Protection Project is often approached by people anxious about possible forthcoming proceedings, and helps with understanding how it’s an inquisitorial (rather than adversarial) process, explains that family members can write statements for the court, can speak to the judge, and that – if they are litigants in person – the judge is supposed to help them in line with the Equal Treatment Bench Book. And Heather wants to contribute to this public education and support about the Court of Protection. That’s her key interest – not revealing private information about her daughter. Celia ended by saying that preventing Heather from talking about her experience has a chilling effect on transparency and open justice.

The Official Solicitor (representing Heather’s daughter)

Counsel for P, Rachel Sullivan acting via her litigation friend the Official Solicitor (OS) did not oppose the application. She stated that in considering the application, the court is faced with balancing P’s right to private life (Article 8) with her mother’s right to freedom of expression (Article 10). Neither right has precedence over the other, and the court is faced with a fact-sensitive balancing exercise.

Although P has a legitimate and reasonable expectation of privacy in relation to the proceedings, the interference to P’s Article 8 rights to a private life were likely to be limited and there was unlikely to be ‘jigsaw identification’ of P. If P’s identity were to be revealed, there is a hypothetical risk of harm to P but it is unlikely to materialize. Against that, Heather’s Article 10 rights were being restricted by the current order – and her motive for speaking out was not a self-serving purpose but to create greater understanding of the court, and this is “compelling” and should “carry weight”.

Heather’s daughter had been asked about the application and (although it seems she did not really understand the meaning of confidentiality), she was “unconcerned”. Her response was that she trusted her mum and is “okay with it if Mum’s okay with it”.

P’s father

P’s father (also a party in his own right) stated simply that he wasn’t opposed to Heather’s application either, as long as P’s safety was not compromised. “Like any parent”, he said, that was his “priority”.

Counsel for the Local Authority (Wokingham Borough Council)

Finally, Counsel for the LA, Verity Bell, set out the local authority’s position, opposing the application, under three headings.

The principal reason for the local authority’s opposition was protection of P’s Article 8 rights. She’s a young adult with her whole life ahead of her and once a decision was made to make information about her mother’s role in the Court of Protection public, that decision would have a degree of permanence. Any information that Heather put out in her name, for example on social media, would be there forever. The subject matter of the proceedings is personal to P: that the court has a role in her life, that she is deprived of her liberty by the state – these are all things that will be on permanent record. Counsel continued by saying that although P might trust her mum now and be content with her mum’s decision now, her feelings might evolve as she grew older. On that primary basis, counsel for the LA stated that the curtailment of P’s Article 8 rights were not outweighed by Heather’s Article 10 rights.

Two other arguments were that if Heather is able to speak out about her role in a Court of Protection case, then other family members might be identified (despite the fact that they’re still covered by the Transparency Order); and that Heather’s rights are not in the wider public interests (“she’s not seeking to hold the state to account – the benefit accrues only to a small pool of potential families seeking her guidance or support”). She concluded by stating that P is entitled to expect a degree of privacy and the infringements to her Article 8 rights are not justified or proportionate.

Judgment

The judge then gave his decision – and ruled in favour of the application.

He stated that P’s mother wished to tell her story of her COP experience not from an anonymous impersonal position but to be able to say “my name is – ”, and to assist others by physically getting involved in person (not simply anonymously in writing), and “there are a goodly number of people who likely will wish for some assistance”. He said there is a human-interest story that is wholly lacking if someone can’t say “I am who I am and I can assist you if you wish”. There is a legitimate public interest in the Court of Protection.

It was also very important that there’s no evidence of likely harm to P in the unlikely event that she were actually to be identified. P herself “has the utmost trust in her mother to act in her best interests and I accept that: both mother and father have acted in her best interests in the past and will do so going forward. Neither of them will cause her risk of harm. Why would HW do anything other than seek to protect her daughter from harm? The balance of harm firmly falls down on side of HW.”

The judge said he did not see that there is a need for Heather to be limited to saying that she was simply a “relative”: he is satisfied that the personal element of a “mother” is better: “Every member of the public likes a personal interest story” – and “Heather Walton”, as he started to call her, (having referred to her as HW before), is the “mother” of a P in the Court of Protection. There is the ability for her to be able to assist other people going through COP proceedings. She has an Article 10 right to say who she is and a true story adds a very important element. She has a personal wish to assist other people and tell her story.

The judge then confirmed that he would allow the amendment to the Transparency Order, allowing Heather Walton to be named.

There was then a discussion about what “undertakings” might be asked of Heather – and this proved quite difficult to sort out (e.g. saying that P’s “private life” was not to be disclosed was felt to be too broad and unenforceable). It was finally agreed, on the suggestion of Counsel for the OS, that the court order should say – as a recital rather than as an “undertaking” – that Heather would not seek to disclose details of P’s daily routine or care. The judge agreed that this was a sensible, practical and pragmatic way forward. And, after 50 minutes, with those words, the hearing ended.

I could see that Heather was beaming.

Reflections

In my opinion, the judge came to a very pragmatic and sensible decision.

To me, it is odd that the only thing a Transparency Order prohibits is a person mentioning that their loved one has been involved in a COP case.

Heather has obviously found being involved in court proceedings stressful and distressing. Rather than trying to forget about it, she wants to use that experience to help other families and to help educate professionals about what it is like for families. This will provide support for other families and a better understanding of the Court of Protection. I wish her well.

I also hope this judge’s decision will have implications for other family members who want to tell their Court of Protection story in their own name.

One final thought. It struck me in this hearing that the OS, acting for P, was not opposing the application. The only party opposing the application was the Local Authority. They seemed to be putting themselves in the position of the OS, and saying they opposed it on P’s behalf. I did find that an interesting position, and I wondered why they considered themselves to know better than P’s own representatives what was best for P.

A note from Heather (P’s mum)

I am thrilled to be able, now, to identify myself as a mum of a disabled young adult who has been through the Court of Protection process.

Our court journey was not long (5 months in total) and was a very simple case (not everyone agreed about where she should live). It also ended well in terms of a decision being for the right placement for my daughter (in my opinion). And yet it was one of the most isolating and stressful experiences I have been through.

I knew nothing about the system, I hadn’t chosen to go through the process and I wasn’t financially able to get my own legal representation. For those of us who care for adult children without capacity, the Court of Protection is a bewildering thing. We assume that because we have always cared for them and made decisions for them, that is how it will always be. To be plummeted into court proceedings, where complete strangers who do not know our children will make the decisions is, putting it bluntly, awful. It feels wrong in so many ways.

During the short 5-month case, we experienced three different judges, a change of social worker, changes in solicitor and counsel for both my daughter and the LA, and a variety of “advocates”, some of whom were spectacularly incompetent.

A previous counsel for the Official Solicitor came to one of the earlier hearings with wrong information, which was presented as fact, and with her mind already made up before she had listened to any of the arguments. She was adversarial rather than inquisitorial. So, a real mixed bag of professionals!

My daughter got to the point where she was refusing to speak to anyone about her wishes.

But we were saved in the end by the solicitor acting for the Official Solicitor, Eleanor Bulmer of Butler & Co Solicitors who showed great sensitivity and managed to skilfully draw my daughter out and get responses from her without her shutting down. And also by the judge, DJ Bridger, who as Amanda notes, was pragmatic and sensible, but also kind and sympathetic to us as parents.

As anyone with disabled children, or parents or siblings lacking capacity in one or more areas will know, it is rarely our relatives that cause the problem. It is the system – the constant bewildering change of professionals, and the lack of understanding that we, their family, know the person inside out – that causes the stress. The Court of Protection process is like the rest of our lives, only on speed – totally reliant on the knowledge and skill of professionals – some who are much more skilled, knowledgeable and sensitive than others.

I genuinely hope going forward that I can share the journey alongside other parents going through the experience. And also, that I can hope to make professionals more empathetic and understanding regarding the impact on family members. They have a job to do: but for us, it is our life.

I look forward to working alongside others with the Open Justice Court of Protection Project and would like to pass my heartfelt thanks to Celia Kitzinger, without whose incredible knowledge and understanding of the system I would not have been able to get this result.

A note from Celia Kitzinger

I’ve made – and helped others make – hundreds of court applications for variation or discharge of Transparency Orders. But this one was special.

Most of the variations I ask for are to permit naming public bodies (like the Local Authority or the ICB or Trust). In fact, the original TO used in Heather’s daughter’s hearing prohibited identification of the local authority – and that was the first thing I asked the judge to change (and it was changed without difficulty, as it usually is). When the variation I’m applying for is to permit identification of a family member, it’s always been after the protected party has died (e.g. the sad case of Ella Lung). Until now. Heather’s daughter is very much alive!

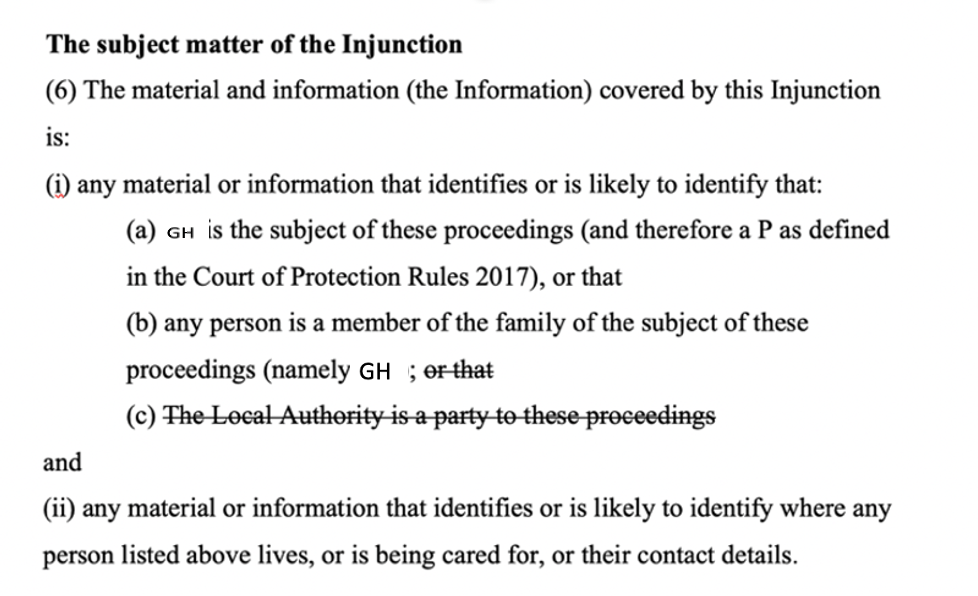

Here’s what the TO looked like after the judge removed the clause prohibiting identification of the Local Authority, but before he ruled that Heather could be identified. It’s the “standard” form of the Transparency Order.

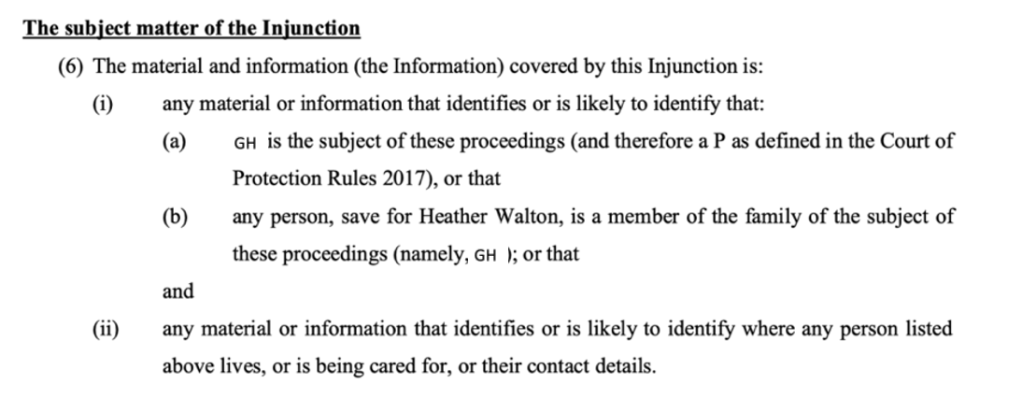

Here’s how it looks now (we only got the sealed order this week, in early December) – with the clause prohibiting identification of the local authority removed, and “Heather Walton” added as an exception to the clause preventing identification of the family. With this small but significant change, Heather is free to share her story.

It took time to achieve this result. Heather first contacted me on 29th November 2023, saying she’d like to make herself available to support other families involved in COP proceedings, and we quickly identified the problem that this wouldn’t be possible with the TO in place. Heather made a formal application to vary the TO on 8th May 2024 which was heard on 30th October 2024 – and although the judge gave an oral decision on the day, it’s taken a further month or so to receive the sealed order. So just about a year from start to finish. But an excellent result and we’re all delighted.

Amanda Hill is a PhD student at the School of Journalism, Media and Culture at Cardiff University. Her research focuses on the Court of Protection, exploring family experiences, media representations and social media activism. She is on LinkedIn (here), and also on X as (@AmandaAPHill) and Bluesky (@AmandaAPHill.bsky.social)

Heather Walton is the mother of a “P” who was involved in Court of Protection proceedings.

Celia Kitzinger is co-director of the Open Justice Court of Protection Project. She can be contacted through the project email on openjustice@yahoo.com

congratulations to you a person or family who is find themselves involved will find it bewildering, having the help of someone who has gone through the process would be invaluable. Its scary, stressful, your anxiety level go through the roof and you do feel judged and you have done nothing wrong You do get to the point where your mental health suffers.

LikeLike

Thank you so much – yes it is so hard going through it all, and I think everyone feels judged in some way, even if that isn’t true! I am hoping that I can help to assist professionals to see this side of the COP process and now that I can be “myself” this will be so much easier!

LikeLike