By Celia Kitzinger, 16th March 2025

Everybody makes mistakes sometimes. Even judges.

Some mistakes can be inconsequential: a typo, a bit of grammar that doesn’t make sense, paragraphs wrongly numbered. I’m not complaining about mistakes like that, what someone on X described (in response to my complaints) as “dotting the ‘i’s and crossing the ‘t’s”. Obviously it would be better if judges did pay attention to details like this – and goodness knows they are often enough described as “pedantic” and obsessed with precision of language – but I have better things to do with my time than correct these sorts of errors.

The mistakes that really matter include, for example, breaching the privacy rights of the person at the centre of the case. Or mistakenly banning observers from naming public bodies, paid for with our taxes and accountable to the public. Or not making it clear who is being referred to when injunctions say we can (or cannot) name someone under certain circumstances (it does needs to be clear which person exactly!).

Transparency orders are injunctions from the court that come with penal notices. It says on the face of the order that if we disobey them, we may be found guilty of contempt of court, and then sent to prison, or fined, or have our assets seized. That means I want to be very sure I understand what it is that the court is telling me I must not do. You’d think the court would want to be sure too – and that they’d make these orders as clear as possible. But in practice, they’re written in complex legal language that make them difficult for most ordinary members of the public to understand. Worse still, they’re often riddled with errors – as we’ve documented many times before.

For example, some orders say we can’t name public bodies – and in our experience that’s a mistake about 90% of the time. But there’s that other 10% or so when the judge has decided that there are good reasons for a public body not to be named (e.g. to protect P’s privacy) – so even if it is a mistake (and we know it probably is) -if it’s in a court Order, then we can’t just go ahead and name the public body and then say if the court objects: “oh I assumed it was a mistake in the order, as it usually is”. The consequences (both for us and for the person at the centre of the case) are too serious if we get it wrong. If the order says we can’t name a public body, then we can’t name the public body: our Project won’t publish a blog post that names the public body if the Transparency Order forbids it – however unlikely it is that the judge actually intended to stop us from doing so (see: What to do if the Transparency Order prevents you from naming a public body).

So, we’re constantly emailing court staff asking them please to check with the judge whether that’s a mistake, and please could the judge correct that mistake if it’s wrong. Sometimes corrections are done quickly – especially if the judge is able to deal with it right away, orally, in the course of a hearing – but even then it can take an hour or so of our time to write a formal letter explaining the mistake and citing the relevant law. Sometimes it can take weeks or months to get obvious mistakes corrected – especially if we’re required to fill in a formal application form (a so-called COP 9) and then, sometimes, go to court ourselves to defend our position. I describe one case where it took four months here: Prohibition on identifying Public Guardian is “mistake not conspiracy”, says Judge.

It’s got to the stage now where I dread opening the electronic documents labelled as transparency orders that pop into my inbox when I ask to observe a hearing. Will there be mistakes? How much of my time (and the court’s time) will it take to correct them? And why, oh why, can’t judges get it right first time (as some, eventually, do, see: “Getting it right first time around”: How members of the public contribute to the judicial “learning experience” about transparency orders).

Five mistakes in one transparency order: COP 14225316 (HHJ Robertshaw) – and listing errors for good measure

This blog illustrates the problem with transparency orders by showing five mistakes in one of them. This transparency order was made by HHJ Robertshaw sitting at Bristol Civil and Family court on 18th March 2024. Her order was kept on file and used for subsequent hearings in the same case. The hearing I attended was nearly a year later, before a different judge, District Judge Mark Tait, sitting in the County and Family Court at Gloucester and Cheltenham on 28th February 2025. That’s the first time I saw this transparency order – sent in response to my request to observe the hearing – though I’m pretty sure there must have been several other hearings in the same case, with the same transparency order in the bundle each time, and nobody noticing the mistakes.

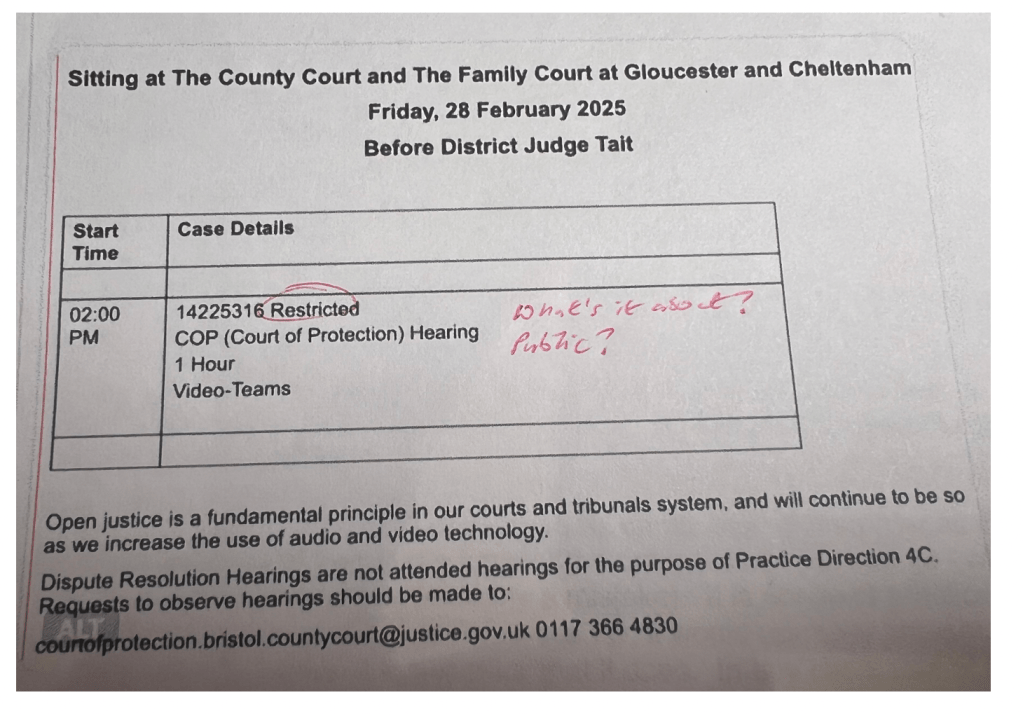

In fact, the mistakes with this case began before I even received the transparency order. Here’s how it was listed in Courtel/CourtServe, which is the only way members of the public normally learn about cases.

Obvious errors here: the word “restricted” shouldn’t be used for Court of Protection hearings (I think it’s intended to refer to the fact that there is a transparency order, which is what it should actually say). There’s no information as to what the case is about (there’s a drop-down list of menu options (e.g.”deprivation of liberty”, “section 21A”, “capacity for internet use” etc) that hasn’t been deployed; and it doesn’t say that it’s public. There’s also no case name. The case name that should, I learnt later, have appeared in the listing was: “Gloucester County Council v TD“.

And then I was sent the transparency order (it had been “approved” by the judge, and “sealed” by the court) – and my heart sank. I got out a red pen and started correcting it.

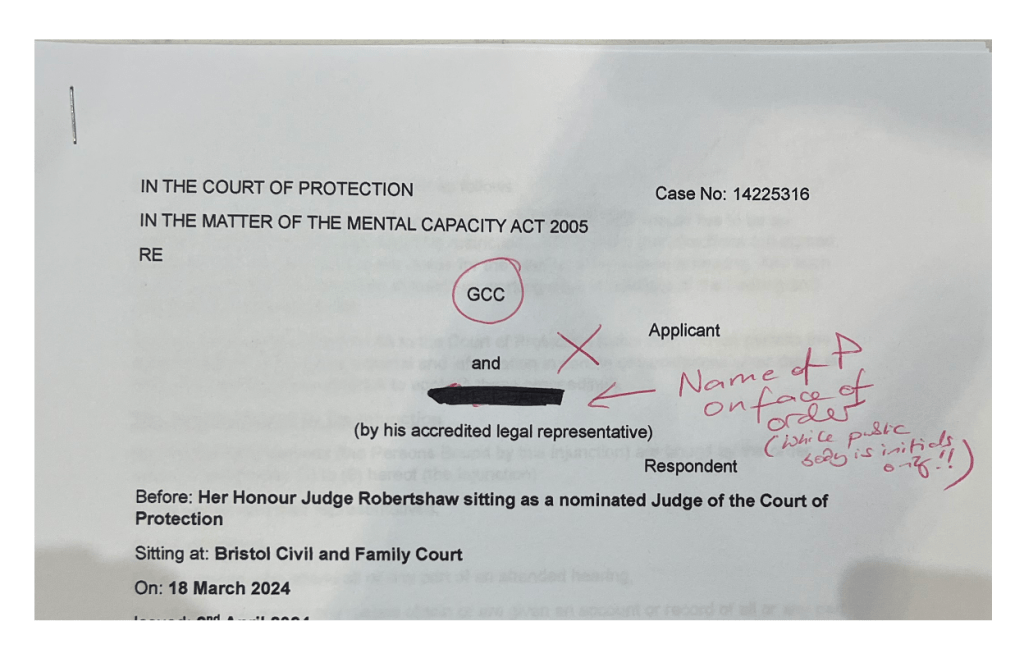

Mistake Number 1

Look at the face of the order: I’ve photographed it below. The applicant is listed as “GCC” (which I quickly figured out must be Gloucester County Council, since the case was being heard in Gloucester – but this should have been properly spelled out on the face of the order). The respondent is the protected party at the centre of the case – by his accredited legal representative (ALR as they are routinely referred to in COP jargon, all explained here: “Accredited legal representatives in the Court of Protection“). Contrary to all the guidance, his full name is displayed on the face of the order. Instead the court should have assigned initials – and in fact, it had: in this case, I later learnt, the initials chosen were TD. (Obviously I’ve concealed his name in the image below).

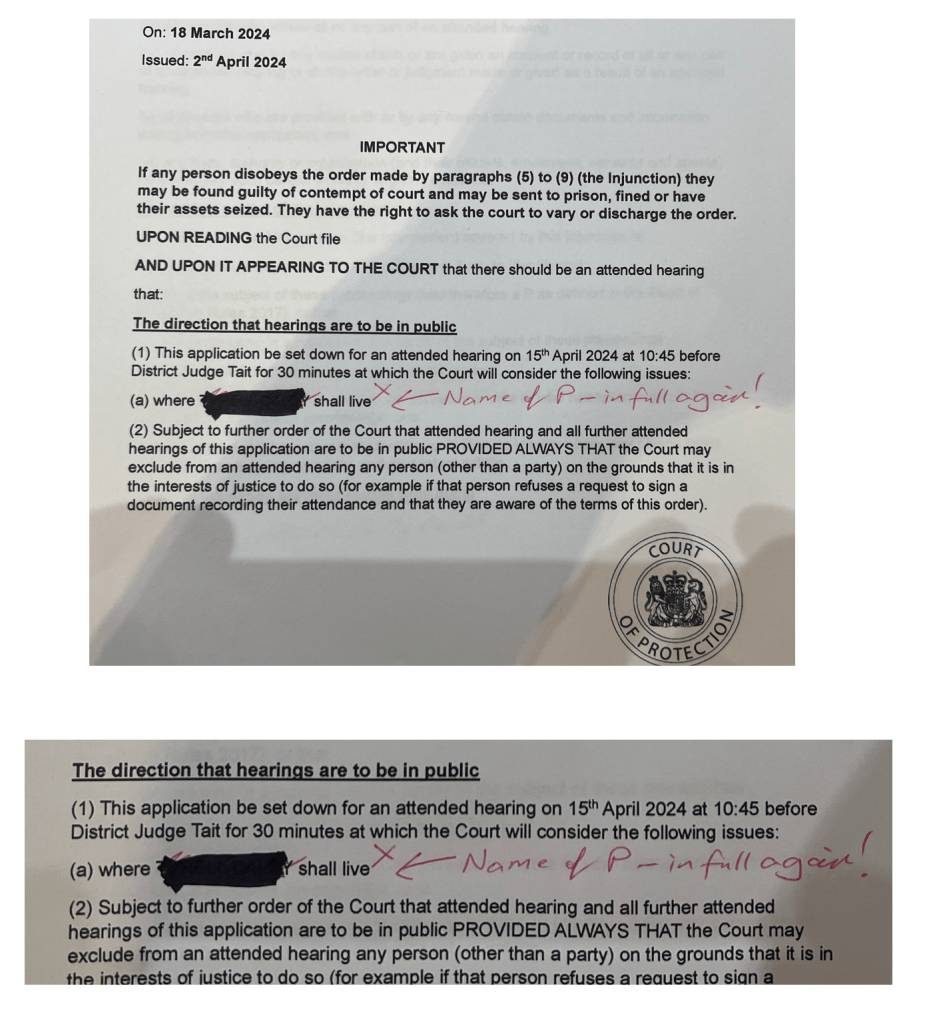

Mistake Number 2

The name of the protected party also appeared (twice) in the body of the order itself. That shouldn’t have happened. The assigned initials should have been used instead.

Mistake Number 3

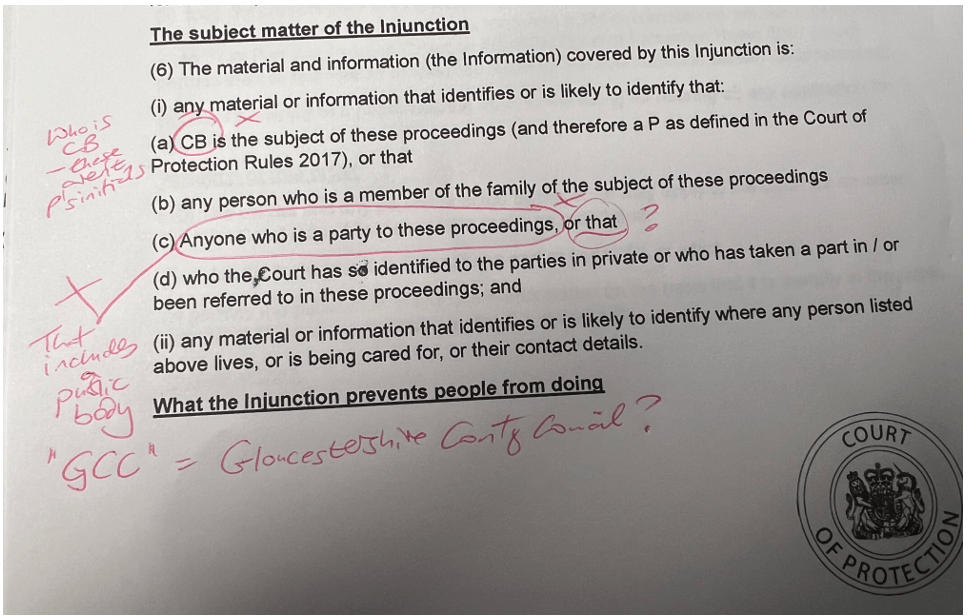

Then there’s a paragraph where some initials are used – but they aren’t the initials the court has assigned to the protected party in this case (TD) but someone else’s initials (“CB”) – and CB is described as “the subject of these proceedings” – which they clearly are NOT. Was someone perhaps using a previous template and forgot to delete the last person’s initials?

Mistake Number 4

Having put the protected party’s name on the face of the transparency order, and referred to him (twice) by his name in the body of the order – and failed adequately to protect him since 6(a) above protects someone called “CB” instead – the order finally does belatedly provide P with some possible protection by preventing us from publishing anything that identifies or is likely to identify “anyone who is a party to these proceedings” (though we’ve been told in 6(i)(a) this is “CB” not “TD”).

Unfortunately, the formulation in 6(i)(c) can be read as covering all parties, including the public body – which isn’t named on the injunction but is referred to by its initials on the face of the order as GCC. So, another order apparently banning us from naming a public body. (Oh, and the words “or that” at the end of (6)(i)(c) make no sense – I suspect because there are missing initials for another person which should have been at the beginning of (d).)

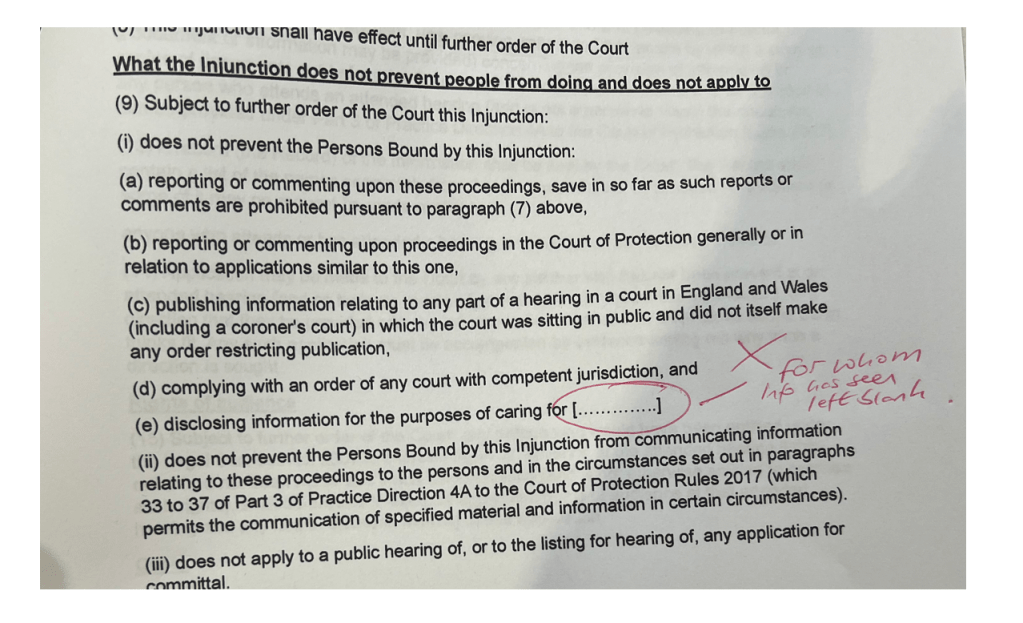

Mistake number 5

Then there’s an order that information can be released “for the purposes of caring for […..]” 9(i)(e) – and who is that? No initials fill the blank. I presume that is where TD’s initials should have gone.

Correcting the mistakes

Once I’d looked through the transparency order and marked up the mistakes in red ink, I wrote a careful, detailed respectful email to the judge who was hearing the case (who wasn’t the judge who’d made this transparency order) asking him please to correct the errors. I sent this to the court staff, by replying to the email address from which I’d received the transparency order. It took me about an hour to make sure I’d spotted all the mistakes and write the email explaining to the judge what they were and why they needed correcting.

The formal process for making changes to a transparency order involves filling in a form (with all sorts of information extraneous to requirements for this purpose) and then sending it to the court, waiting for it to be “issued”, and then for a judge to look at it and make a decision about where the matter should go from there. It can take months! I said in the email that I hoped to circumvent this process: “I know I can make a formal COP 9 application to vary the TO, but I wonder if it might be more efficient (and less costly of court time) if I simply note the following points, which I would be grateful if you could raise with the judge before the 2pm hearing“. And then I listed the corrections required.

It was frustrating to get a response from the court staff saying: “Thank you for your email. I understand that you are trying to save some time by not submitting a COP9 application however an application needs to be filed for a Judge to review and/or amend the transparency order“. I know that’s not true in practice. Judges have often reviewed and/or amended transparency orders without my filing a formal COP 9 application – on the basis of either an email, or my oral submissions in court. In an email forwarding this response to senior HMCTS staff I commented: “this is nuts!” (for which intemperate language I subsequently apologised). I was surprised that senior staff too confirmed that “The process to amend the transparency order provided for by the Judge is as mentioned to file a COP9, the Judge will need to consider the points formally and any amendments required, and therefore a COP9 should be submitted, this is the process as set out within the Courts procedures.”

By now it was 12.14 and the hearing was at 2pm, and my hope that the judge would deal with it swiftly at the beginning of the hearing was fading fast. I spent the next 45 minutes cutting and pasting my email onto a COP 9 form, wrestling the form into submission (it didn’t want to take as many characters per text box as I’d written) and filling in extraneous information required. It did not feel like a productive use of my time to do this, nor did I think it a good use of the court staff’s time to have to process a formal application this way.

Depressed by the COP 9 response, and envisioning this as another episode that was going to drag on for months, I asked three other members of the public to request the link and come along to the hearing to see how it was dealt with. It was fairly shocking to me that after I’d already informed the court about the problems with the transparency order (especially the risks posed by circulating a document with TD’s full name on it), all three of the additional observers were sent the transparency order, uncorrected.

A happy ending?

I received a response to my original email (not to the COP 9 form submission) saying the judge could see no difficulty with my requests for variations to the transparency order. Then right at the beginning of the hearing, after everyone had been introduced, DJ Tait said “The transparency order was made by HHJ Robertshaw and issued on 2nd April 2024. I’m grateful to Professor Kitzinger, who raised issues with the order, and I’m minded to adopt every recommendation that she makes. It’s important to get it right.” Then he went through the order, instructing counsel to make all the changes I’d pointed to, saying again that he was “grateful”. So, that was good.

But it had taken hours of my time – and involved other observers and court staff, and also occupied about five minutes of court time during the hearing, plus the time the lawyers would now have to spend correcting the mistakes on the order. And, several weeks later, I’ve not received the corrected version of the order. It would all be so much better if they could get it right first time around.

There’s another cost too. It turned out that TD is a young man who’s in an unregulated placement which isn’t suitable for him. The local authority has located an alternative placement, but is unable to identify a registered manager to manage the placement. They’d offered the job to one person, but then had to withdraw the offer after that person tried to change the conditions of employment. TD’s mother was in court and quite distressed by what was going on. She said it was “overwhelming“. She felt “frustrated, disappointed – all this is taking so long. I feel quite emotional“. She wasn’t blaming anyone and nobody seemed to think it was anyone’s fault, and everyone seemed to be working very hard to try to solve the problem of TD’s placement. But it was obviously an upsetting time for TD and his mother. It’s unfortunate that the judge’s attention was diverted, at the beginning of the hearing, onto the transparency order instead of being able to address, right away, the substantive business of the case. It was also unfortunate that nobody had prepared TD’s mother for the possibility of observers in court. I don’t know if she minded us being there (one observer thought she did; I thought her focus was on her son and we were no more than a peripheral irritation) – but I wish the corrections hadn’t been necessary.

Here’s what two of the other observers said:

“My overall impression is one of sorrow for ordinary people involved and how little they will probably be aware of the impact of these types of errors. Clearly privacy was important to Mum, upset that no notice was given about observers being present – and she kept her camera off the whole time. The system needs appropriate controls and accountability when errors keep being repeated. In my opinion, it’s sloppy, harmful and unneccesary. Goodness knows there are enough well-remunerated people in these processes who should be preventing this occurring.” (Angela Killeavy, public observer)

“From my experience, I suspect they involve cutting and pasting of previous Transparency Orders and they often seem to be an afterthought, a supplementary part of the process of preparing for a hearing. I just don’t think that those involved in drafting them have any idea of their impact” (Amanda Hill, public observer)

I know that, in the real world, it’s not judges who literally compose these transparency orders. Someone else (paralegals, or solicitors?) tries to paste the relevant information into a template and puts it before the judge. But judges are approving them (surely, sometimes, without reading them?!) and off they go to be sealed by the court. In my view, the buck stops with the judge. It’s their order.

Everyone makes mistakes – even judges! But it takes all of about 3 minutes to spot mistakes in transparency orders (if only someone would check them before sending them out to observers) – and it’s surely not that hard to get them right in the first place? And when observers do spot mistakes and proffer corrections, we really appreciate the swift and courteous response of judges like DJ Tait.

Celia Kitzinger is co-director of the Open Justice Court of Protection Project. She has observed more than 600 hearings since May 2020 and written more than 100 blog posts. She is on LinkedIn (here), and also on X (@KitzingerCelia) and Bluesky @kitzingercelia.bsky.social)