By Celia Kitzinger, 20 July 2025

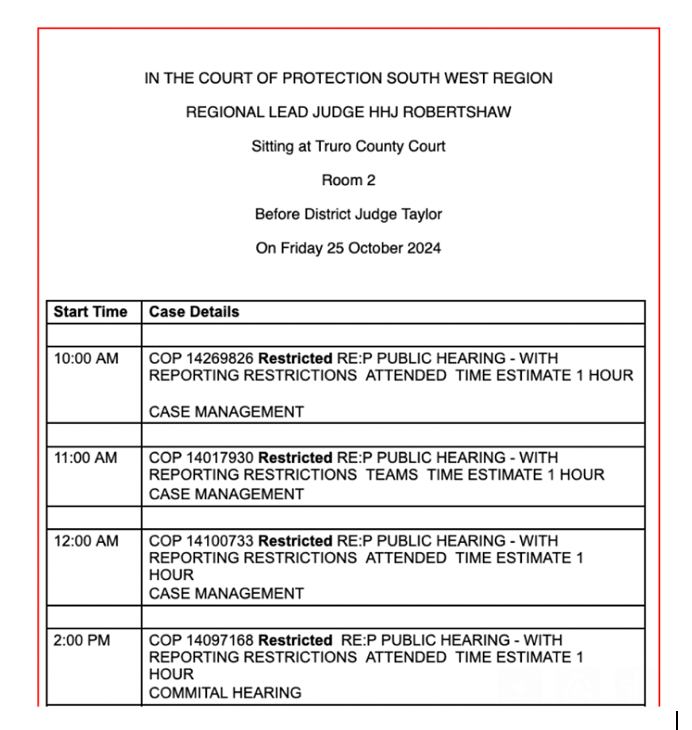

Since October 2024, I have been asking the Court of Protection (via the Bristol hub) for information about what happened at a committal hearing before DJ Taylor sitting in Truro at 2pm on Friday 25th October 2024. It’s COP 14097168 – the last in the CourtServe listing below.

The hearing was listed as public, but when I asked to observe it, I was not sent a link. Instead, I was told it had been vacated. This seems not to have been true – and I was subsequently promised (but, despite multiple reminders, have never been sent) a transcript of the hearing.

Today I learnt what happened at the hearing from which I was excluded. I discovered that the case heard by DJ Taylor in October 2024 subsequently went on to be heard a couple of months later by a different judge (HHJ Paul Mitchell), and he published a judgment (Committal for contempt of court: Council v Orange and others), one paragraph of which (§14) reports on the 25th October hearing.

I now know that at the October committal hearing (the one I was told had been vacated), the judge (DJ Taylor) handed down a suspended prison sentence of 7 days and also attached a “Power of Arrest” order to the injunction previously made (and previously breached) forbidding the contemnor from going to the home of the protected parties. (The alleged contemnor was not – I think – represented at that hearing. I don’t know who represented Cornwall Council at that hearing, but it may well have been Christopher Cuddihee, who represented the council at the hearing with which the judgment is concerned).

I had to google “Power of Arrest” since I’d not come across it before. It’s “a power attached to an order that enables the police to arrest a person whom they have reasonable cause to suspect of being in breach of the order, even though that person may not be committing a criminal act. Where a power of arrest is attached, the police do not need a warrant to arrest the person in breach of the order.” (Thomson Reuters Practical Law Glossary, “Power of arrest”).

The problem, I now know, is that DJ Taylor did not have authority to make a “Power of Arrest” order, and should not have done so.

The effect of the judge’s “Power of Arrest” order at the hearing from which I was excluded was that the defendant was wrongly arrested when he breached the injunction again. HHJ Mitchell who heard the case two months later says so in his judgment:

44. … [I]n my Judgement the Power of Arrest should not have been added to the Injunction Order.

45. The Court simply had no power to do so, sitting as a Court of Protection. That Power has since been removed, but it does mean that there was an element of wrongful arrest.

Committal for contempt of court: Council v Orange and others

In determining sentencing, HHJ Mitchell takes into account “that [the contemnor] was wrongfully subject to a Power of Arrest” (§46).

I have checked this point of law with a number of Court of Protection (and other) lawyers and am confident in reporting that the Court of Protection can’t attach a “Power of Arrest” directly. This is because the High Court cannot do so under its inherent jurisdiction (Re FD (Inherent Jurisdiction: Power of Arrest)) and the Court of Protection’s powers here are derived from those of the High Court. The Court of Protection can put a penal notice on an order, and a breach of that notice can lead to committal proceedings, and, in turn, to arrest. But DJ Taylor did not have the power to make a “Power of Arrest” and that action short-circuited the procedure[1].

One of the oft-quoted purposes of open justice is to “keep the judge himself, while trying, under trial,”[2] as the eighteenth-century jurist Jeremy Bentham proclaimed.

If I’d been admitted to the hearing before DJ Taylor, my ears would have pricked up at the phrase “Power of Arrest” and I’d have started googling it and then asked around (as I have done now). I’d have written a blog post within a week of the hearing saying something to the effect of “Oi! DJ Taylor has done something I don’t think the judge has the power to do“. Or if, unaccountably, I hadn’t researched it and simply written a blog reporting the facts of what happened, I think it’s quite likely that some of the lawyers who read our blog posts would have spotted the problem for themselves. Either way, I’m optimistic that it would somehow have got back to DJ Taylor who would have corrected the error – and the defendant wouldn’t then have been subject to wrongful arrest two months later.

This illustrates one important reason why hearings need to be open. There was, in all likelihood, a cost to justice in excluding me from that hearing – not just a cost to the abstract principle of transparency as a good in and of itself, but quite possibly a concrete practical cost to the administration of justice. Keeping the judge, while trying, under trial, can sometimes be a reality – even for members of the public who observe hearings.

I don’t know why I was not admitted to the hearing and I don’t know why I haven’t been provided with the transcript I was promised.

My primary concern in writing this blog post is not the committal proceedings as such but rather the lack of transparency about what has been going on – and its implications for my belief in the integrity of the justice system. There are only so many times you can say “cock-up, not conspiracy” before it begins to sounds like a hollow refrain.

Background

25th October 2024

I sent an email, time-stamped at 11.49am, asking to observe the committal hearing. At 14.05, I received an email from an administrative officer at the Bristol Civil and Family Justice Centre saying: “I would like to confirm that this hearing has been vacated”. This seems not to have been true.

I responded by thanking the administrative officer for that information but also pointing out that the listing of the hearing seemed to be non-compliant with the relevant Practice Direction in that neither the name of the applicant nor the name of the person alleged to be in contempt of court had been published. So, I asked for this information.

28th October 2024

I was sent a “response from the judge” telling me that the applicant was Cornwall Council and the alleged contemnor was David Orange. I was also told: “No further hearing listed – matter dealt with today. I have ordered a copy of the judgment to be transcribed and will be requesting that the hub publish through the appropriate channels.” That judgment has never, to my knowledge been published.

I wrote to senior HMCTS staff asking: “Please can you investigate urgently how it came about that I was informed by Bristol Admin Officer, [NAME], that this hearing was vacated when the judge tells me that the matter was in fact dealt with that day”. I received no response.

11th/12th November 2024

I contacted the court to say, “I have been looking out for this judgment and have not yet located it. Can someone advise me when it will be available (and where) please”. I got a reply the next day: “The transcription is not yet available, we will let you know once we receive it.”

26th- and 28th February 2025

I’d been intermittently checking for a published judgment, and failing to find one, and had heard nothing further from the court, so I wrote again. “Hello – is this judgment available yet please? The matter was dealt with in October 2024 and I was promised a transcript when one was available – which I imagine it might be more than three months later?” (26th February 2025)

This reply came through a couple of days later. “Thank you for your email. The transcript for case 14097168 has been requested. I apologise, we have not yet received a copy of the transcript, when this becomes available I will provide you with a copy of the transcript for the hearing that took place on the 25 October 2024.” (28th February 2025)

3rd March 2025

I acknowledged the reply of 28th February and asked for more information. “Thank you for letting me know that the transcript is not yet available. It does seem to be taking a rather long time. Is it possible please to know – in the interests of open justice and transparency – whether a finding of contempt was made, and if so what the penalty was please.” (3rd March 2025)

I have never received a reply.

16th May 2025

I tried again: “Is this transcript ready yet please? The hearing was on 25th October 2024 so it’s been more than six months now.” I have never received a reply.

So, over the course of more than six months, I was aware that someone (a person called David Orange) had been before the Court of Protection for alleged contempt of court, and that he must have faced the possibility of a prison sentence. But I had no idea whatsoever what Cornwall Council alleged he had done, or what the injunctions were that he was said to have breached. I did not know whether or not the judge had found him guilty. I did not know whether or not he had been sent to prison. When I asked for this information, I simply got no response. This is not open justice.[3]

HHJ Mitchell’s published judgment

Today, in the course of reviewing the dismal history of my attempts to get information about this case, and poised to send yet another letter to the court, I discovered that a judgment has been published about this case: Committal for contempt of court: Council v Orange and others. It was published on the judiciary website (which is hard to search) and not on BAILII or the National Archives, which we regularly check for judgments. It’s not a judgment from the hearing I’d tried to observe, but from another hearing a couple of months later before a different judge. But it does report on what happened at the hearing I was excluded from.

The published judgment is dated 6th January 2025. I’d been told in late February 2025, when I asked for the judgment, that there was no transcript available for the earlier hearing – and if that is true, it might explain the vagueness and apparent uncertainty in HHJ Mitchell’s judgment, which is hedged about with provisos in relation to earlier proceedings[4] . But on reading this judgment, I was able to discover what happened at the October hearing – and what I have learnt only adds to my concerns about transparency.

Rather surprisingly, the published judgment names not only David Orange but also the “two vulnerable elderly people”, both of whom have dementia, who are the protected parties in this case[5]. The published judgment also gives the full postal address of the home where they live (also referred to as “the Property”). I have not reproduced that information here, because – although this information has now been publicly available on the judiciary website for more than six months – it seems an invasion of their privacy and not necessary in the interests of transparency[6].

It turns out that there was an injunction (issued by DJ Taylor on 9th July 2024[7]) against David Orange saying that he “must not return to enter or attempt to enter [the Property] except with prior agreement of Cornwall Council”. This was to protect the viability of the care package for the “two vulnerable elderly people” which was at risk due to his “obstructive behaviour”, “aggression”, and “verbal abuse” towards care providers commissioned by the local authority. The hearing I’d asked to observe concerned breaches of that injunction.

The judgment by HHJ Mitchell records:

On 25 October District Judge Taylor dealt with a Committal Hearing. That was in respect of an allegation of breach of the Injunction or allegations of breaches I think on three separate occasions, when David was said to have been at the Property in breach, and the Judge found the breaches proved. The Court duly imposed a suspended prison sentence of 7 days suspended for 6 months. A Power of Arrest was added to the Injunction. (§14, Committal for contempt of court: Council v Orange and others).

As I was reading the judgment, I paused at this point to google “Power of Arrest” since I’ve not seen it added to an injunction before. I’ve seen judges make “bench warrants” – and I wasn’t sure if they were the same thing. It seemed not. It looked complicated. I asked some lawyers for help, both privately and publicly on X and Bluesky. I learnt that the court has to fill in Form N110A (click here) which asks for the “statutory provision” under which the “Power of Arrest” order is made – and I don’t know how that was completed in this case since (lawyers tell me) there doesn’t seem to be any statutory provision for “Power of Arrest” in the Court of Protection.

In any case, perhaps predictably, David Orange breached the orders again, after the hearing of 25th October 2024. Given that the judge at that hearing had added Power of Arrest” to the injunction, his breach (going to the home of the protected parties) led to his being arrested by the police on 6th December 2025 and held in custody for some period of time (HHJ Mitchell is not sure how long – “He appears to have been held or detained for less than 24 hours” §43).

A committal hearing was listed for 19th December 2024 but adjourned since David Orange did not attend court. He didn’t attend the subsequent hearing either, but the court decided to proceed anyway. The judge said, “Plainly, proceeding in his absence is potentially prejudicial to him, but I have to say that it is unclear if anything is to be gained by putting this off on a further occasion because all indications are that non attendance is deliberate.” (§23, Committal for contempt of court: Council v Orange and others).

The judge considered evidence from the police officer who arrested David Orange at the Property (who recognised the defendant as someone he’d been at school with). He heard from the lead social worker who confirmed that “there is no record of David Orange being in touch with the Local Authority requesting or agreeing any arrangements to visit the Property” (§31). The judge was “entirely satisfied that the Council has established the case beyond reasonable doubt” (§33) and (after making sentencing reductions relating to the unlawful arrest and the period of detention already served and considering the sentence in its “totality”), he determined on an overall total of 14 days imprisonment for contempt of court.

So, finally, I know what happened to David Orange.

Conspiracy?

Over and over again in my dealings with the Court of Protection, I tell others – and I tell myself – that the problems we face are “cock-up not conspiracy”. I share the perspective articulated by my colleague on the Open Justice Court of Protection Project, Daniel Clark, in a recent blog post reflecting on the errors in Transparency Orders. He said: “I try not to see conspiracy behind the multiple transparency failures of the Court of Protection. The judicial system is busy and overstretched, and mistakes are (unfortunately) inevitable: links won’t be sent in time, listings won’t be always accurate, video links won’t always be set up.” (Prohibitive Transparency Orders: Honest mistakes or weaponised incompetence? )

The problem is that there are just so very many transparency failures. Adherence to the view that the Court of Protection is basically striving for transparency requires us to believe in cock-ups on an industrial scale.

In this case, I’m prepared to believe that the listing of 25th October 2024 was botched (or, more technically, non-compliant with the Practice Direction) as a result of error – since naming people in listings doesn’t come naturally to staff in the Court of Protection, and committal hearings requiring this are relatively scarce. Also, the names of the applicant and the alleged contemnor were swiftly provided on request. But why was I told by an HMCTS staff member that the hearing was vacated, when DJ Taylor told me two days later that the matter had been dealt with that day, and that a transcript of the judgment had been ordered? Why, despite the judge’s offer to send me the transcript and my multiple requests, have I never been sent a transcript of that judgment? Why was I left to discover for myself, in HHJ Mitchell’s judgment some months later, a vague summary of what happened at that hearing? Could the apparent “cock-ups” in transparency relating to DJ Taylor’s hearing possibly have anything to do with the fact that he made an error of law, resulting in unlawful arrest? I’m not asserting that, but it becomes harder and harder to believe that everything I’m encountering is unmotivated cock-up.

No part of my experience of this hearing has been transparent. And sadly, the experience I’ve had with this case is not so very dissimilar to my experience of seeking transparency in other committal cases, including notably the case of Tia Bench – a judgment I chased for almost two years (see the Postscript and subsequent Update to this blog post). My faith in the judiciary’s aspiration to open justice is becoming increasingly strained by the weight of experiences like these: they could easily be read as evidence that actually transparency is not much valued, and may even be deliberately obstructed. There are days I feel like giving up.

Judges continue, of course, to trot out the slogans. Justice must not only be done but be seen to be done. Publicity is the very soul of justice. Sunlight is the best disinfectant. Even the one about how transparency keeps the judge, while judging, under trial – which might in fact have had direct relevant to this case and prevented an unlawful arrest.

But fine words butter no parsnips.

Celia Kitzinger is co-director of the Open Justice Court of Protection Project. She has observed more than 600 hearings since May 2020 and written more than 100 blog posts. She is on LinkedIn (here), and also on X (@KitzingerCelia) and Bluesky @kitzingercelia.bsky.social)

Footnotes

[1] Thank you to the lawyers who took time to answer my questions about this including Alex Ruck Keene and Jacob Gifford Head.

[2] Jeremy Bentham, “Draught For The Organization Of Judicial Establishments, Compared With That Of The National Assembly, With A Commentary On The Same” (1790), quoted (for example) recently by Mr Justice Cobb in a speech entitled “Justice must be seen to be done”

[3] I referred to this case in my submission to the Ministry of Justice Law Commission Consultation on contempt of court.

[4] For example, HHJ Mitchell says (the emphases are mine): “The Local Authority commenced welfare proceedings in the Court of Protection in, I think May of this year…” (§5); “[X] has, as I understand it, significant health and social care needs…” (§6); “I think [Y], also needs significant support…” (§7); “ I think that was in the autumn of ’23…} (§8); “allegations of breaches I think on three separate occasions (§14).

[5] It’s not entirely clear from the judgment whether or not both of them (they are husband and wife) are protected parties, or just the husband.

[6] Other published committal judgments avoid naming protected parties and have certainly not provided contact information for them. Where possible (it’s not always possible), other judgments have also avoided specifying the nature of the relationship between the contemnor and the protected party. In my view, based admittedly solely on my reading of this judgment, there is no reason why this should not have been so in this case. There seems no reason to publish the names of the “two vulnerable elderly people” at the centre of this case, and no reason to give their home address. Other people are also named in the judgment including the police officer who arrested David Orange and two different social workers.

[7] The judgment, published on 6th January 2025, does not state the date of this hearing. It has been transcribed from an oral judgment delivered in December 2024 (I think 30th December 2024 is implied by §19). There are several references to events “this year” which must be read (despite the January 2025 date of the published judgment) as referring to events in 2024 (e.g. “May of this year” §5; “on 9 July of this year” §11).

2 thoughts on “Wrongful arrest and a secret prison sentence: DJ Taylor (Truro) and the failure of open justice”