By Claire Martin, 25th August 2025

Transparency and open justice are principles at the heart of our justice system. Last year, the Lady Chief Justice created a Transparency and Open Justice Board, chaired by Mr Justice Nicklin, who said that the Board will “set objectives for all Courts and Tribunals, focussing on timely and effective access in terms of listing, documents and public hearings”. (Mr Justice Nicklin’s speech at the workshop held by Court & Tribunals Observers’ Network on 4th June 2025 at Green-Templeton College, University of Oxford, can be found here).

Mr Justice Nicklin acknowledged that transparency cannot be achieved merely by allowing members of the public and journalists to enter a court room (either in-person or via a remote link). Simply being present in court does not necessarily mean that we can understand what’s happening. We need to be able to grasp what key issues are at stake in any given case; what the relevant facts are (and what remains uncertain and needs to be established); what statutes and case law apply and how they are interpreted; what is disputed between the parties and why. Without this, we can’t observe or appreciate that (or how) justice is being done.

I’ve observed over a hundred hearings in the Court of Protection since I became involved with the Open Justice Court of Protection Project in 2020. Even though I am more familiar, now, with the language used in this court, and some of the procedures and ways of working, hearings can remain impenetrable to me – and to other observers – if the court launches into a hearing as if everyone in the court knows the background to what’s happening.

So, what is ‘effective access’? As observers, we do not have access to the documents in the court ‘bundle’. If we’re observing a hearing in a case we’ve not watched before, and if the court does not provide us with either an opening summary and/or the position statements, then it’s like joining in the middle of a complicated conversation. We don’t have a clue what is happening and have to (try to) piece things together as we go along.

Three things that really help any observers in court are: (i) Position Statements ii) Opening summaries and (iii) Approved orders. Here’s why.

(i) Position statements

Position statements are especially helpful because they set out each party’s current position in relation to the matters before the court. Typically, they are somewhere between one and eight pages. They generally list the “essential reading” from the bundle to which observers do NOT have access (e.g. expert reports, witness statements) and then rehearse the background and basic facts of the case and set out the party’s position with reference to relevant statute and case law.

The current situation, since Poole J’s judgment in Re AB [2025] EWCOP 25 (T3) is that observers can request, and counsel can provide, anonymised position statements without need for permission from a judge. The guidance says: “If an observer wants to see a party’s position statement they should ask the party in advance of the hearing and state their reason. If they cannot contact a party in advance of the hearing (whether at court or otherwise) they may make the request (with reasons) to the court and that request can be passed on to the party or their representatives.” (§36(4))

We usually cannot “contact a party in advance of the hearing” because – unless we have been following a case over successive hearings (and even then, counsel can change) – we don’t know in advance who is acting as counsel. That information is never on the public lists.

Since the Re AB judgment was handed down on 15th July 2025, the Open Justice Court of Protection Project has amended its guidance for observers to advise asking for position statements at the outset, when emailing to request the link for a hearing (if observing remotely) or on spotting someone official (like a court usher) or someone recognisable as a member of a party’s legal team (if observing in person).

When we request position statements, we are required to give a reason for wanting to see them, but Poole J acknowledges that there is a “low threshold” for what constitutes a good reason, “at least where what is being sought are copies of skeleton arguments or written submissions which are central to an understanding of the case, and that in many or most cases it will be easily cleared” (§27). The wording suggested by the Project is: “so that I can follow the hearing and to support accurate understanding and reporting of it”. This has never been queried and seems to be routinely accepted as a legitimate reason.

If any party refuses to send a position statement, Poole J’s judgment sets out a procedure whereby we can make an oral application to the judge (§36(7)).

It sounds straightforward in theory. In practice, it’s rather more complicated.

(ii) Opening summaries

Way back in 2020 the then-Vice President of the Court of Protection, Mr Justice Hayden published guidance making “a small practical suggestion to improve access to the business of the Court when press or other members of the public join a virtual hearing”. He pointed out that “[w]hilst the judge and the lawyers will have read the papers and be able to move quickly to engage with the identified issues, those who are present as observers will often find it initially difficult fully to grasp what the case is about. I think it would be helpful, for a variety of reasons, if the applicant’s advocate began the case with a short opening helping to place the identified issues in some context. This is my usual practice when sitting in court ….”

This turned out to be a valuable suggestion from Mr Justice Hayden. An opening summary of the facts of the case and the issues before the court was then, and remains now, very helpful in orienting us as observers at the outset of the hearing. If we don’t get PSs, or only get them a few minutes before or after a hearing begins (which, understandably, is often the case), an opening summary is especially important.

We rarely receive PSs with sufficient time to read and digest their contents in advance of a hearing. This is because hearings are generally not listed until the evening before the day of a hearing, and unless we know a hearing is on a specific date – and who all counsel are – we cannot request PSs until then. Inevitably, our emails are not read and actioned until the next working day. So, an opening summary is important for transparency even when PSs may have been provided in the minutes before or after the start of a hearing (or when there is an intention – or direction – to provide PSs subsequent to a hearing). Also, we’re not lawyers and PSs can be dense legal documents and hard for us to follow. In addition, there are often advocates’ meetings between parties after the PSs are written, meaning new developments may have been communicated to the court via subsequent emails, so the parties and the judge are proceeding on the basis of information which we don’t know about.

We generally get opening summaries when the judge asks counsel to provide them, or provides one themselves (which in my experience has been frequent). Sometimes judges ask observers if we would like an opening summary, which is helpful. Sometimes counsel ask if they can provide one if the hearing seems otherwise set to proceed without one.

A good opening summary typically includes: basic details about P including diagnoses/impairments of mind or brain, and any determinations as to P’s capacity; what issues are before the court (and any disagreement between the parties); and what the judge needs to decide. These opening summaries can usually be provided in just 3 or 4 minutes.

(iii) Approved Orders

An approved court order (as described here by the National Legal Service): “… records an official judgment or way forward, as agreed by a Judge. A court order can be final (at the end of a hearing) or interim (which is in place until a final order can be made). What is in the order depends on the case presented to the judge and what evidence is necessary for just determination of the particular case”.

We can request from the judge the approved order from any case heard in public (to which we have a right under COP rule 5.9) aftera hearing has concluded, but they are sometimes not sent (even after repeated chasing). One judge (HHJ Redmond) recently asked counsel to send me the approved order without my asking for it, which was very helpful and efficient, saving email requests to the court office staff, who we know are overburdened in their roles.

Four case studies

Two weeks after the hand down of the judgment in Re AB, (between 28th and 31st July 2025), I observed four hearings (all remotely) in the Court of Protection, and it’s these I’m drawing on as case studies to illustrate how the provision of position statements, opening summaries and approved orders to members of the public actually works in practice.

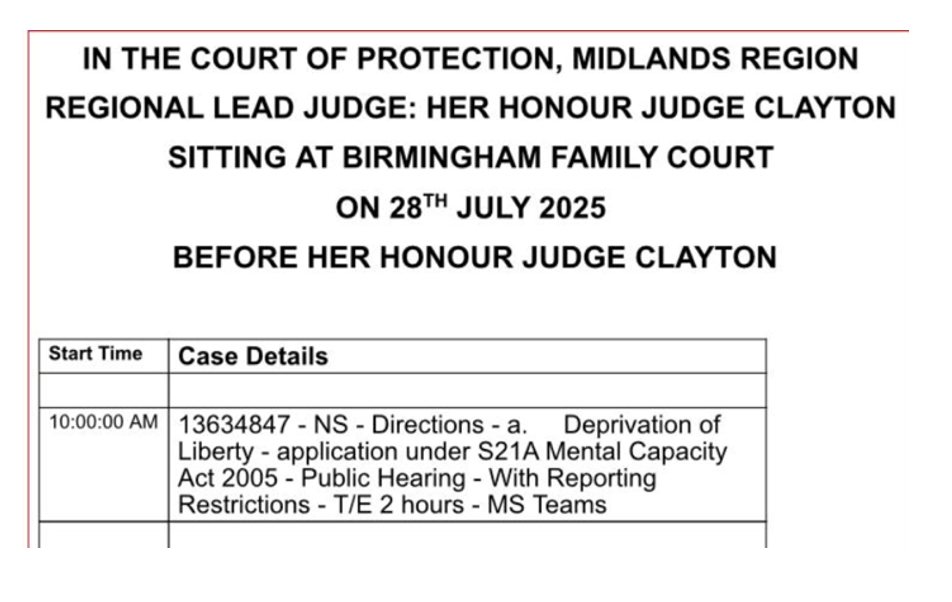

The hearings were (1) COP 13634847 before HHJ Clayton, Birmingham; (2) COP 13851997 before DJ Glassbrook, Northampton; (3) COP 20000888 before DJ Lucas, Slough; and (4) COP 20006349 before DJ Lucas, Slough. In this blog I will focus on what happened following my request (in each of the four cases) for Position Statements (requested in advance of the hearing) and approved orders (requested after the hearing). I will say for each hearing whether or not there was an opening summary (provided by whom and how), and consider the extent to which each hearing was actually transparent to me as an experienced observer seeking to advance the judicial aspiration for transparency. What’s clear from my experience, I think, is how much work it takes – for observers, court staff, counsel, solicitors and judges – to try to fulfil the judicial aspiration for open justice in the Court of Protection.

Most Court of Protection hearings are held not in London before specialist and Tier 1 (T1) judges, but in county courts across England and Wales. The four hearings I observed (summarised below) were in Birmingham, Northampton and Slough before T1 and Tier 2 (T2) judges. Each of the four hearings concerned key matters of legitimate public interest: an objection to a deprivation of liberty (1); a ‘‘failed Re X” case (2); arrangements for two sisters who had been ‘decanted’ from their home due to hoarding and cuckooing (3); and the management of what the judge described as “a war zone” between family members and carers for a woman with dementia (4).

So how did the courts do with transparency in relation to these hearings concerning matters of legitimate public interest.

Position Statements

Across these four hearings, I received only ONE position statement in time for the hearing itself (sent ten minutes before the hearing began). The other PS in that first case (before HHJ Clayton) had apparently been filed only 3 minutes before the hearing began, and the judge hadn’t seen it either (1).

In relation to the second hearing (before DJ Glassbrook), I was told that there were no Position Statements filed, and for the third (DJ Lucas), that there were position statements but the judge hadn’t received them yet.

In the case of the fourth hearing (DJ Lucas again), I received no PS before the hearing started, despite the judge having tried to help by emailing the court office, asking for my request to be passed to counsel so that they could send me their PSs before the hearing. I have since received all three: two during the course of the hearing and one the next day after it had been anonymised.

There were seven Position Statements prepared in total (the hearing before DJ Glassbrook had no PSs) across these four hearings. I received one before the hearing, two during the hearing, and one the day after the hearing. That means that I have received four of seven PSs, and three are still missing despite follow-up email (and chasing) requests.

Opening summaries

There was no opening summary for two of the hearings (before HHJ Clayton and DJ Lucas). In one case the judge (DJ Glassbrook) provided an opening summary; in the other (the second one before DJ Lucas), there would not have been one but that counsel for P via the Official Solicitor (Gemma Daly) intervened to ask the judge’s permission to give an opening summary for me as an observer (thank you!), which was immediately granted.

Approved orders

Three of the four orders (all requested on 3rd August 2025) have still not arrived more than three weeks later, despite chasing. I don’t know why not. In relation to DJ Lucas’ orders, I was told that one was delayed until a date for the next hearing had been decided on, and I received the other on 20th August 2025. The approved order I’ve received is extremely helpful to me because it sets out clearly what was directed by the judge at the hearing, meaning I don’t have to rely entirely on my (contemporaneously typed) notes if and when I report on that hearing, which (in this case before DJ Lucas COP 20006349) I hope to do after the next hearing.

Problems on the ground

Here’s more detail about each of the cases, focusing on the problems as they emerged on the ground.

1. HHJ Clayton, COP 13634847 – Birmingham (28th July 2025)

This was the first time I was asking for Position Statements since the Poole J judgment (and guidance) in Re AB. So, I asked for the TO and PSs and cited Poole J’s judgment in my email requesting the link for this remote hearing.

I almost gave up on this hearing (listed for 10am) as it hadn’t started by 10.30am, but at 10.40am I was contacted by counsel for the OS, sending me the PS and asking whether I had received the TO. I replied saying I hadn’t received the link to observe – or the TO. The link then arrived – but no TO. A court officer sent me the TO at 10.49am and I was admitted into the hearing at 10.51am. So, in this case, I received the (anonymised) PS from a party before getting the link to observe the hearing or the TO.

I looked at the PS and it sounded an interesting case concerning a 70-year-old man with a diagnosis of Korsakoff’s syndrome, alcoholic amnestic syndrome , ‘cognitive impairment disorder’ (wonder whether they mean ‘mild cognitive impairment’ – since ‘cognitive impairment disorder’ isn’t a recognised diagnosis), COPD, rheumatoid arthritis, macular degeneration, anxiety and depression. He is objecting to his current supported living residence, which is why the case has come to court. He wants to go back to the area where he lived before and be near his family. He is divorced and his three children don’t want any contact with him, sadly.

It’s a best interests decision and the Local Authority has, seemingly, been dragging its feet. It also transpired (much to the judge’s displeasure) that the Local Authority (LA) had not filed their PS until 3 minutes before the start of the hearing. I have emailed the ‘solicitor advocate’ for the LA (Patricia McCausland) requesting their PS but I have not (yet) received it.

My engagement with the important issues in this case was overshadowed by the judge’s behaviour towards me as an observer.

There was no opening summary, but the judge addressed my request for PSs. In this particular case, the hearing was on a Monday, so I had emailed over the weekend (which we as observers often do, having read the listings on Friday afternoon or evening). She said that if I email my request at the weekend when the ‘court offices are closed’, there’s very little time to respond on the day. I spoke up and said that public listings (via Courtel/CourtServe) don’t usually appear until close or subsequent to office closing hours the day before a hearing, so it’s not usually possible to request either the link to the hearing, or the Position Statements, any sooner than the evening before. The judge didn’t respond to this. She said they had delayed the start of the hearing to ‘deal with [my] request’. She also said she didn’t know why I thought the hearing started at 10am when it had always been listed to start at 10.30am. It may, I suppose, have been listed at 10.30am in the judicial diary, but it was most certainly listed for 10am in Courtserve – as displayed below. Judges often don’t know how their cases appear in the public lists.

It’s unsettling to (in effect) be told off by a judge in open court. I have been told – many times – by judges that I should request links and documentation ‘earlier’ – and that’s frustrating advice, since it’s simply not possible to follow it. If we’re at work (which most public observers are), then given the time at which public listings appear, we can’t email until that evening or (given domestic responsibilities) first thing the following morning – or (for Monday hearings like this one) over the weekend. The Open Justice Court of Protection Project has previously published blogs by those of us chastised by judges for what feels to us like something entirely out of our control. We wish judges would understand that – and appreciate the negative effect on transparency and open justice of their apparent irritation and misplaced advice (see: Why members of the public don’t ask earlier to observe hearings (and what to do about it) and If this had been my first court observation, it would have been my last!)

The default assumption from the judiciary seems to be that we observers have failed to make timely requests when we could and should have done so (and are consequently making unbearable demands on the court) – when in fact the public listing system does not support transparency, or enable us to make earlier requests, as it should.

2. DJ Glassbrook, COP 13851997 – Northampton (31st July 2025)

At this hearing, there were just four people: me observing, the judge, one lawyer (Anslem Billy, acting for Northamptonshire County Council and not a barrister but an ‘Adult Social Care Lawyer’ according to his email signature) and P’s sister (who is applying to court to be her sister’s 1.2 representative). [I had not received anything except the link in advance of the hearing – no TO and no PSs.]

The judge, DJ Glassbrook, was very welcoming. He immediately addressed the fact that an observer was present at the hearing (I think so that P’s sister understood) and read out the Transparency Order (which was in ‘standard’ terms – preventing the identification of P or any of P’s family), saying it is ‘his practice’ not to anonymise public bodies. It transpired that the one lawyer involved did not have the Transparency Order either.

The judge explained the situation to the sister very straightforwardly. “The Court hearing is not private. People not directly involved may attend. Ms Martin is an example – nobody may publish anything ….. [he explained the standard TO and not anonymising public bodies] …. There is an injunction which gives her the details. Ms Martin quite properly asked for the Transparency Order. The challenge that I have is that, unlike a High Court judge, I do not have a clerk. I don’t have time for emails. I have to do my best to fit things around other hearings. I had hearings at 10 o’clock this morning, and 11 o’clock and 11.30. The time before 10 o’clock was preparation for other hearings. So, I simply don’t have the wherewithal to deal with things as promptly as perfect. When Ms Martin asked for the Transparency Order, I sent an email back to the central hub in Birmingham saying ‘Please let her have a copy’.”

The judge asked me if I wanted to comment. I asked if he wanted me to put on my camera (‘Yes why not!) and then said ‘You have observed before – indeed we have met before’. I agreed that we had, and said I hadn’t received the TO. The judge said ‘That doesn’t surprise me’. I also said that I’d requested the PSs for the case, to which the judge replied ‘I don’t think we have any?’ The lawyer confirmed: “There is no PS!’.

I know – from looking frequently at court listings – how judges’ daily lists often include back-to-back (or even simultaneously listed) hearings. We also know, at the OJCOP Project, that around one in three hearings is ‘vacated’ (cancelled) on or just before the scheduled hearing day. Perhaps this is why judge’s diaries are so jam-packed. But what if they do all go ahead? That morning, for DJ Glassbrook, was one of those mornings. I was left wondering what judges’ employment contracts contain, and whether they are allowed breaks or a cup of tea. And then they have observers requesting things from them on top of all that. Open justice is a fundamental part of our system, but it can’t be the most efficient use of a district judge’s time, or a cost-effective use of staff skills, for them to be sending and chasing emails to court staff asking for documents to be sent to observers.

It was the judge who provided the opening summary. P is a woman (I don’t know her age) with a diagnosis of schizophrenia. She lives in ‘bespoke accommodation’. The Re: X fast-track application was declined (by a previous judge). I knew from Eleanor Tallon’s blog that, sometimes: “‘Re X’ applications are made, and upon reviewing the evidence, the court decides this streamlined process is not appropriate and the case needs to be heard”.

DJ Glassbrook explained that, in this case: ‘capacity evidence is not the most stringent I have seen’, expressing consternation that the capacity report from the consultant psychiatrist contained ‘bald assertions rather than, ’This is the conversation, these are the answers I had back and from that it is apparent that….’. That bit is not there. And then, retain information, it is more a bald assertion rather than ‘the reason I come to this decision is’”. The solicitor said that everyone agreed that P lacked capacity for the decision in question, including P’s sister, and that the hearing had been listed on a ‘fast-track process’. The judge said ‘That may be right, that we have the correct interim declaration, but I need to set a final hearing if we get that far. I wouldn’t be very chuffed if we get there and the evidence doesn’t stand up. We do not have the necessary evidence to make final declarations: the evidence not strong. Of course, the fundamental point, firstly, if this lady has capacity, [is that] I don’t have jurisdiction, and if she HAS capacity then any deprivation of liberty cannot possibly be authorised by anybody and it would mean she’s free to get up and go wherever she likes. I know it’s not a s.21a case but there are similarities. I am being asked to authorise deprivation of liberty, and I can’t do that if she’s got capacity.’ [Judge’s emphasis]

DJ Glassbrook was very facilitative to P’s sister, explaining the options for legal aid, what a 1.2 representative needs to know, and the advantages and disadvantages of becoming a party (one disadvantage being that ‘if we end up having an independent expert on capacity, all parties would need to chip in on paying for that’).

The judge had (in a previous hearing, that I didn’t observe) directed that an ALR be appointed – it hadn’t happened, so he picked one himself and told the lawyer to sort it out and ensure P’s sister got all the documentation. He asked the lawyer to send me and P’s sister the TO. I tracked down the email for legal services in Northampton County Council and sent him my email and I received the TO later that same day, and a promise to send me the sealed order when it’s available. The next hearing for this case is Monday 22nd September via MS Teams.

3. COP 20000888 – DJ Lucas, Slough (31st July 2025)

At both this and the 3pm hearing on the same day (my fourth case study), DJ Lucas was very efficient and helpful. He welcomed me to the hearing and checked that I had received the Transparency Order (which I had, along with the one for his next – 3pm – hearing, at 07.43 from the court hub).

I think 7.43am is very early for court staff to be sending out TOs. I had received an auto-response from the Reading hub (which Slough comes under), saying: ‘HMCTS staff are working under significant pressure due to a lack of staff and the current urgent need to triage, list, vacate, and re-list cases. Your enquiry will be addressed, but it will take longer if these are alongside emails asking for updates’. The whole system seems under enormous strain.

Counsel for P started by stating that the PSs for the hearing had been ‘filed late’. DJ Lucas said, ‘I don’t have any PSs. Unfortunately, at three minutes past two they haven’t made their way to me’. That explained why I had not received them prior to the hearing.

But then the court launched straight into the substantive matters of the hearing without an opening summary. I found it hard to understand at first. I gleaned that the applicant is Wokingham Borough Council, represented by Louise Thomson and that P was represented by Tim Baldwin, via the Official Solicitor.

The case concerned a woman (I don’t know her age or ‘impairment/s’) who is currently living in ‘decanted’ accommodation: what an awful phrase – they all used it – she’s not a bottle of port! She’s been ‘decanted’ with her sister, while their council house (in her sister’s name) is being deep cleaned and repaired. There is some suggestion of ‘cuckooing’ and some unsuitable associates of P’s sister, who also seems to have her own challenges. She hoards, which led to a rat infestation (hence the ‘decanting’). The local authority wants P to move to independent supported living and has identified a suitable place. They want P’s buy-in, and she seemed keen on the move when her sister was not there, and then less keen when she was. So, there was some suggestion of inappropriate influence or even coercion and control, but it was not explicitly named. The OS position was not settled on a view as to whether P should be (forcibly) separated from her sister, with whom P wishes to stay living. The judge said ‘her sister seems to have a strong presence – the expert report is that her sister has a lot of influence over her’.

It then transpired that P and her sister have been ‘decanted’, together, for almost two years. At first the judge thought it was one year, saying: “The sisters have been decanted from their home for a year now. Well, if it were my home and I was told I would have to move out for a 2-day job to be done and here we are a year later, I suppose [there’s] clearing up to be done, but even so this is an extraordinary amount of time”.

The judge wants a statement from the Local Authority housing department about why the works are taking so long. Counsel for the LA said that delays were ‘due to completing electricity checks at the property’, and the judge replied ‘Does it take long for an electrician to go round? Is it that extraordinary for a Local Authority with housing stock to carry out an electricity check?’. My thoughts exactly.

Interestingly, once he realised that it was two years since the sisters had been ‘decanted’, the judge floated a theory that it might be ‘convenient’ for the local authority that the property isn’t ready for them to move back to, stating ‘that is how it appears’.

The plan is for the LA Social Worker to show the proposed new accommodation to P on her own (without her sister) and to ascertain P’s own wishes and feelings about the proposal to move there (without her sister, since it was reported that ‘it seems likely’ that the placement would not accept P’s sister as well – another unknown that the judge asked to be clarified by the next hearing). The case might end up with the LA applying for authorisation to force P to live separately from her sister, but they are not yet at that point. The case is back in court in the week commencing 13th October 2025 (or as soon as possible thereafter).

I managed to follow quite a lot of what was going on in this hearing, even without the PSs or an introduction – this is because the judge himself had not received the PSs and counsel needed to apprise him of their positions.

4. COP 20006349 – DJ Lucas, Slough (31st July 2025)

At this 3pm hearing DJ Lucas opened proceedings by introducing me as an observer and asking if I had been sent PSs. When I said ‘No’, he said (with marked irony) ‘That’s great news, because I specifically asked the court office to ask for them to be relayed and specifically requested that her email be forwarded to allow that to happen. Sorry they have not reached you. My apologies. I have tried my best to facilitate’.

The judge checked and none of the lawyers had received my request from the court office. The judge asked me to put my email in the group chat and for them to forward the PSs to me, and he reminded counsel at the end to send me their PSs. I received two PSs during the hearing and the third the next day.

Although he didn’t remember to give (or request) an opening summary to this case (or the previous one that I observed before him), DJ Lucas had clearly tried very hard to arrange for me to be sent PSs in advance of the hearings. There has to be a better way to get this done than using up judges’ time like this.

The case was very interesting. It concerns residence and care for P, who is a 90-year-old woman with dementia who lives in her own home with her daughter (L). Another daughter (D) was in the hearing. At home P has live-in care, with a new provider: that’s because service from the previous provider broke down. Issues before the court relate to residence and care in her own home, and also to the Lasting Power of Attorney for Health & Welfare that L holds. The COP has suspended this LPA during these proceedings, in part due to allegations against L by the Local Authority. There are currently no contact restrictions in place and no person has proposed, at the moment, that P should move from her own home, but there have been suggestions (from a previous social worker) that she should move to a care home. The applicant is the Royal Borough of Windsor and Maidenhead (represented by Michael Paget). Both daughters are to become property and affairs deputies and no one disagrees with this.

Proceedings have been going on for some time (the TO I was sent was dated November 2024). Efforts to try to improve relationships on the ground between L and the carers have been made – and there continue to be allegations against L by the LA (and vice versa). A fact-finding hearing regarding these allegations is likely. A ‘schedule of allegations’ needs to be properly compiled and meanwhile, in the approved order (which I received on 20th August) there is a ‘Schedule to Order’ setting out the expected behaviours for both L and the carers in relation to caring for P and communications between them all.

It looks like the next hearing will be ‘mid-Oct to mid-Dec’, so (given that we cannot – unlike journalists – sign up for ‘alerts’ for specific hearings from the court) I will need to keep checking the listing in Courtel/CourtServe for hearings in Slough in those months to ensure I do not miss it.

Conclusion

These four case studies show the problems with transparency in practice in relation to position statements,

- 4/7 position statements (only one of them before the hearing) – but not a surprising finding when the judges hadn’t received them in advance either

- 2/4 opening summaries – judges simply forgot about these when under pressure of time and trying to also to sort out the position statements for me, and for themselves

- 1/4 approved orders – the other three are quite likely still stuck in the system somewhere and not yet available to anyone, three weeks later, and one awaits listing of a next hearing before it can be finalised.

Despite this, I think everyone – including the judge who chastised me – wanted to deliver on transparency. Expressions suggestive of frustration, exasperation and cynicism that the system would support the judicial aspiration to transparency were common across the hearings. The problems are systemic as the whole justice system seems to be unravelling without sufficient staff or resourcing.

There are so many places where things can go wrong. Court staff at regional hubs (from which we request links to observe) don’t always pick up our emails in time to forward our requests to the court at which the hearing is actually taking place. The hearing courts then don’t receive our requests in time to send us link. Even when the requests are passed on before the hearing to the judge, judges’ diaries can be so choc-a-bloc that they simply don’t have the time to give the go-ahead for a link (or to approve court documents to be sent). And even when the judge does receive an email and seeks to ensure that the observer gets a TO and PSs, as the cases before DJ Lucas show, this is sometimes not actioned in time by court staff – probably due to an unrealistic list of demands on the overburdened court staff, rather than any deliberate obstruction. The outcome is the same though – open justice becomes the casualty. It’s clear that judges themselves are frustrated by this.

Court staff seem run off their feet in many hearings we observe, and they almost always appear to try their best to facilitate access for observers; district judges’ listings look wholly unrealistic to an outside eye, with no time for a comfort break, lunch or simply time to think. Like seats on an aeroplane, they are booked in the expectation that some will not be filled (which is often so and is another cause of problems for observers (see “a day in the life of a court observer” for an observer’s experience of multiple vacated hearings). Requests for approved orders seem to get lost – most likely in the avalanche of duties for court staff. When court staff, lawyers and judges already feel harassed and overburdened, it can feel as if open justice needs to go to the end of the queue.

If Nicklin J’s words are going to butter any parsnips then the court system needs to grapple with how it can efficiently respond to people who want to understand what happens in court and grant us (as Nicklin J hopes) “effective access in terms of listing, documents and public hearings”.

Claire Martin is a Consultant Clinical Psychologist, Cumbria, Northumberland, Tyne and Wear NHS Foundation Trust, Older People’s Clinical Psychology Department, Gateshead. She is a member of the core team of the Open Justice Court of Protection Project and has published dozens of blog posts for the Project about hearings she’s observed (e.g. here and here). She is on X as @DocCMartin, on LinkedIn and on BlueSky as @doccmartin.bsky.social