By Celia Kitzinger, 20th September 2025

Note: The protected party died on 8th July 2025. I offer my condolences to his fiancée, his family, and his friends.

A document labelled a “Living Will” was at the centre of this case (COP 20006397) heard before Mr Justice Poole in the Royal Courts of Justice.

The family of the protected party (AB) claimed that this document was not valid, not applicable to his current situation, and not a genuine document produced by him of his own free will[1]. The hearing I observed on 30th June 2025 was supposed to be about the authenticity of the “Living Will” .

The issues of validity and applicability had already been dealt with in earlier hearings: the judge had ruled that the advance decision to refuse treatment (ADRT) contained within the “Living Will” was, if authentic, both valid and applicable (AB (ADRT: Validity and Applicability), Re [2025] EWCOP 20 (T3) (10 June 2025)). So now the question was, is it authentic?

The family said it was not an authentic document. They alleged fraud (that it wasn’t AB who had written or signed the document) and undue influence (that someone – unspecified – had persuaded or coerced him into writing or signing it). If the document was inauthentic, then neither the ADRT it contains, nor the expressions of wishes and preferences (e.g. in relation to contact with family) that are part of the document, could properly be taken into account in making decisions about his treatment and care. I haven’t seen the whole document, but a significant part of the Living Will is helpfully reproduced in the judgement cited above.

In the most recent blog post about this case, another observer and core team member of the OJCOP Project, Claire Martin summarised what’s happened so far:

The story is terribly sad. AB is a 43-year-old man who is being given medical treatment to keep him alive in a minimally conscious state. There’s a document that AB made not long before his brain injury, that he called a “Living Will” (not a legal term, but one which is commonly used), which includes refusals of life-sustaining treatments, including clinically assisted nutrition and hydration (i.e. the feeding tube, which is the main treatment currently keeping him alive). There’s been a dispute about whether these treatment refusals constitute a legally binding valid and applicable Advance Decision to Refuse Treatment (ss. 24-26 MCA 2005). That’s been resolved: the court has now ruled that they do. But the family also says that the document is fraudulent (that it’s not his signature on it) or, if it is his signature, then it was made under duress or undue influence. Meanwhile, the Trust continues to give him medical treatment which is quite possibly contrary to his legally binding instructions, and may also be contrary to his best interests – although these seem not to have been properly addressed. There is a bitter dispute between AB’s birth family and fiancée that is likely to be aired in court at the next hearing on 30th June-3rd July 2025. (Claire Martin, “Preparing for possible future lack of capacity: My advance decision to refuse treatment and the case before Poole J”).

It was listed as a four-day fact-finding hearing, and because ADRTs are a particular interest of mine (both personally and on public interests grounds), I went along to observe in person.

In the event, the case was concluded by the end of the first day. The family decided not to pursue their allegations of inauthenticity. The upshot of that was that the “Living Will” – including both the ADRT and the statements of wishes and preferences – was treated as genuine.

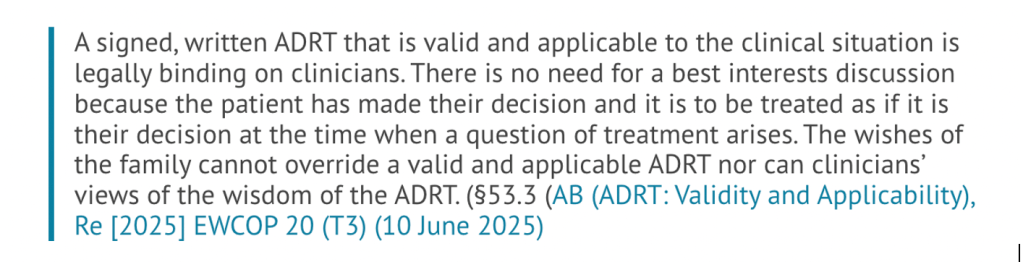

The authenticity of the “Living Will” document has different implications for the two elements within it. One part, the advance decision to refuse medical treatment (ADRT) is legally binding, as if the patient were making a contemporaneous capacitous refusal of treatment – and the court cannot interfere with that decision. The other part, stating wishes, feelings, and preferences, has legal standing and should properly be taken into account in making best interests decisions about the patient, but is not determinative.

In a second published judgment about this case, Poole J writes:

There being no challenge to its authenticity, the ADRT within the Living Will is binding in that it has effect as if AB were now refusing consent to the identified treatment, namely CANH. However, other parts of the Living Will which addressed contact with family members in the event that AB were to lose capacity, which he has, are not binding under the Mental Capacity Act 2005 but are highly relevant to a best interests decision about contact. I was invited to resolve outstanding disagreements about AB’s contact with the Third Respondent, his fiancée, and with members of his family whilst AB is cared for at a hospice. I made determinations about contact in his best interests. (Re AB (Disclosure of Position Statements) [2025] EWCOP 25 (T3))

I will deal with the two parts of the Living Will separately.

1. Advance decision to refuse treatment (ADRT)

Since the judge had already handed down a judgment confirming the validity and applicability of the advance decision to refuse treatment (Re AB (ADRT): Validity and Applicability) [2025] EWCOP 20 (T3), the court’s acceptance that it was authentic as well meant that the ADRT was now constituted as AB’s own legally binding decision. This meant that it was not open to the court to make a ‘best interests’ decision about life-sustaining treatment – because AB had already made his own advance decision in accordance with §§24-26 Mental Capacity Act 2005. A valid, applicable, and authentic ADRT means that it is unlawful to continue any treatment that has been refused – and that included, in AB’s case, clinically assisted nutrition and hydration.

The judge made a short declaration that it was lawful to continue clinically assisted nutrition and hydration until AB could be moved to a hospice, but that transfer must take place within the next seven days. During the period prior to transfer, there must be no escalation of treatment – no cardiopulmonary resuscitation and no antibiotic treatment. At the hospice, he must be provided with palliative care and all life-sustaining treatment withdrawn, in accordance with his own binding advance decision.

It was a sombre and moving experience to hear this in court. It was profoundly sad to understand that AB’s life would now come to an end. It was also (for me) empowering to hear the judge recognise the limits of his authority over AB and to witness how the decision-making power of clinicians and the court was blocked by AB’s autonomous and capacitous decision.

2. Contact – a statement of wishes and preferences

The issue of contact between the family and the patient was more complicated. The Mental Capacity Act 2005 permits us to make legally binding refusals of medical treatment in advance of losing capacity – and AB had done so. But we can’t make legally binding refusals to allow people to visit us after we lose capacity; all we can do is express our wishes and preferences on the matter, and these should be taken into account (alongside any apparent current wishes and feelings) at the point at which best interests decisions need to be made about who visits us. In this case, AB had expressed a strong preference that members of his family should not visit him if he were to lose capacity – and he also explained why that was, expressing some very negative views about them. Not surprisingly, the family were upset about what he’d said about them, and they did want to be at his bedside as he lay dying in the hospice.

As it turned out, AB’s fiancée was content for his family to visit him (as they had been doing frequently ever since his brain injury). This was in part because he was unconscious and not objecting or showing any distress when family were at the bedside.

The Official Solicitor (represented by Katie Scott) made the point that “even if [his fiancée] and the family were able to come to an agreement on contact, it may be that the Official Solicitor will say, ‘well we can’t agree to that because of what he’s said in the Living Will’”. I was pleased to hear this – it gave appropriate weight to his written views, and affirmed for me the value of advance statements of wishes and feelings, even though they’re not legally binding.

The Official Solicitor eventually decided “not to stand in the way of that agreement” between AB’s fiancée and his family. The reasons given were that the patient would be in ‘calm coma’ at the hospice and not in any way aware of his visitors, and – crucially I thought – that a key motivation in not wanting family visits was that AB had wanted to “protect [his fiancée] from the treatment that he perceives she will receive at the hands of his family” (i.e. they’d be unpleasant towards her). The Official Solicitor’s view was that “what this court could do is provide her with that protection – set up ways of them visiting and [his fiancée] visiting with no chance of them meeting”. The parties agreed, and the judge approved, a “contact schedule” with buffer times to avert the risk of family and fiancée running into each other because “regrettably, that would be prone to result in conflict” (as the judge put it).

Implications for everyone planning ahead for future lack of capacity

This case is really significant for all of us concerned to plan ahead for a future when we may lack the mental capacity to make our own decisions about medical treatment, or indeed about anything else. We will publish some more blog posts exploring this in more detail.

For now, it is obvious that we need to ensure, as has always been the case, that our refusals of medical treatment comply with the statutory requirements for an Advance Decision as set out in ss. 24-26 of the Mental Capacity Act 2005. In addition, the most striking lesson from this case is that we also need to pre-emptively protect ourselves against possible claims of inauthenticity on the grounds that we didn’t actually write or sign the document ourselves, or that we were coerced or manipulated into doing so.

Compliance with the statute is not too difficult for anyone using one of the templates produced by competent charities in England and Wales. (These tend to be much better in practice than those I’ve seen produced by solicitors. And they’re free!). I recommend Compassion in Dying. Beware – because there are bad templates out there and I’ve seen many poorly composed ADRTs as a result. I’ve also been dismayed by reliance on templates from other jurisdictions, including American “advance directives” (presumably the result of a google search) and templates produced by Swiss assisted dying organisations: these rarely comply with statutory requirements in England and Wales.

It’s less obvious how to protect ourselves against claims of fraud and undue influence.

In his judgment dated 10th June 2025 Mr Justice Poole summarises the main strands to the family’s argument explaining why he considered it necessary and proportionate to hear the family’s case that the ADRT is a fake document, or was signed under undue influence. He says:

51. Mere assertion of such a case without any grounds might well result in the Court exercising its case management powers to avoid a substantial hearing on those assertions. Here, however, I am satisfied that the Fourth Respondent’s [ i.e. the family’s] contentions merit proper, but proportionate, consideration by the Court:

51.1 There is evidence from the family that the style of language used in the ADRT […] is not at all typical of AB.

51.2 The family has provided evidence that there are plain errors in the documents which suggest that they were not made by AB, for example in the pet-name he gave his grandmother.

51.3 The family has given evidence that some of the assertions made in the documents are at odds with AB’s communications with them at the time.

51.4 The documents were produced so late after AB’s brain injury. It is a legitimate question to ask why those who knew he had made the ADRT would not produce it if it had indeed been made before he lost capacity.

51.5 The document was produced after a significant falling out between [AB’s fiancée] and the family and was relied upon by [AB’s fiancée] to seek to exclude the family from involvement in AB’s life and decision-making about his treatment.

Re AB (ADRT: Validity and Applicability) EWCOP 20 (T3)

Because the family decided, at the eleventh hour, on the first day of the projected four-day hearing, not to pursue their case that the Living Will was a fake or the product of undue influence, I don’t know how these arguments would have played out in court. The two people who witnessed the signature to the Living Will were in court ready to give evidence, but they were never called on to do so – not least because there were concerns that there could have been potential criminal charges against them that had not been spelt out, and they hadn’t been given the opportunity to get legal advice.

The position statement from AB’s fiancée (represented in court on that day by Victoria Butler Cole KC[2]) helps me to understand how she had planned to counter the allegations of fraud and undue influence. She says: “There is no obligation on any person inviting a medical professional to rely on an ADRT to establish in the Court of Protection that it is a genuine document”. So, the starting assumption must be that a legal document (such as an ADRT) is genuine, and allegations of fraud and dishonesty in relation to such documents must be proved on the balance of probabilities, based on evidence and not mere speculation.

In this case, the evidence in support of the fiancee’s position that the ‘Living Will’ is a genuine document, freely created, and reflecting AB’s actual wishes and values includes:

- the court has sworn witness statements from the two men who signed the living will as witnesses to AB’s signature

- these two witnesses are close friends of AB’s, they don’t stand to gain anything by making fraudulent claims about his living will

- the reason why the fiancée was not aware of the living will until August 2024 was because AB didn’t tell her he was making it as he didn’t want to “upset” or “worry” her

- AB’s friends were not surprised that he produced a living will – they gave witness evidence that he’d told them that he had “got his affairs in order in case the worst were to happen”. This followed a series of serious health issues (leading to several A&E visits due to breathing problems) in the run up to his cardiac arrest on 4th May 2025.

- The advance decision to refuse treatment is consistent with AB’s views as expressed to those of his friends who submitted witness evidence (in writing) to the court, and with a tattoo he has which reads “Death is not the greatest loss in life. The greatest loss is what dies inside us while we live”. This is consistent with views expressed in the living will that prioritise quality of life over quantity.

The fiancee’s position statement counters the concerns raised by the family, saying (for example) that AB wrote formal professional documents as part of his work and was perfectly competent to do so (and this was testified to by a colleague); that he used different pet names interchangeably for his grandmother; and that the reason why the living will wasn’t brought to the attention of the doctors before August 2025 was because she was not aware of its existence and the two witnesses were not aware of the severity of AB’s brain injury (as borne out by contemporaneous text messages e.g. between one of the witness’ mother – an advanced health care practitioner – and AB’s fiancée, one of which reads “Thank GOD No Brain damage they will check his cognition when they wake him up”).

The fiancée points out, too, that she has nothing to gain from AB’s death: he has no property, no savings and no life insurance: there is no motive for her alleged dishonesty.

Finally, in relation to the allegation of undue influence, it would be odd (as Poole J observed in his judgment) to manipulate AB into signing the Living Will when he had capacity, and then to fail to bring the document to anyone’s attention for four months after his brain injury.

In any event, these arguments were not tested in court because the family did not pursue the allegations. But it worries me that the circumstances surrounding the Living Will, and the content of the Living Will itself, raised sufficient concerns to the judge that he considered it necessary and proportionate to hear the family’s case. The judge’s decision to hear the family’s evidence caused a significant delay in implementation of (what turned out to be) AB’s properly-made valid and applicable ADRT – a delay of many months during which he was subjected to medical treatments he had lawfully refused. I would want to guard against my own ADRT being vulnerable to this kind of scrutiny by the court. If anyone were to try to question the authenticity of my ADRT in future, I would very much hope that the court would “exercise its case management powers to avoid a substantial hearing“.

None of us would want our loved ones to be placed (like AB’s fiancee) in the position of having to defend the authenticity of our written documents after we’ve lost capacity. We want to produce documents that are sufficiently robust to avoid this kind of challenge. The best I can come up with for now are these three suggestions.

1. Tell everyone about your ADRT and any other statements you’ve made about what you want to happen if you lose capacity to make decisions for yourself. Tell your GP, and your family and friends – including people you really don’t want to “upset” or “worry” – because if things go wrong later, they will be much more upset and worried than if you’d told them at the time. Tell people who you know or suspect will disagree with what you want for yourself, because those are the people who might challenge the document and plant doubts in the minds of clinicians and the courts.

2. Record, in writing, who you have told and what their views are. It’s can be helpful to write (for example) “I’ve told my daughter that I don’t want cardio-pulmonary resuscitation and I’ve got my GP to formally record this in a DNACPR form. My daughter’s very upset about this – she wants me to live forever, but this is my decision and I’ve explained to her why I don’t want anyone to try to get my heart beating again if I have a cardiac arrest. She doesn’t agree with me – so if you’re reading this in a situation where I’ve lost capacity, please give my daughter the emotional support she needs to cope with this, but please respect my wishes and don’t let them be over-ruled by what she wants”. There’s no need to be hostile or angry with people who might disagree with you – but you do want to protect your right to make your own decisions, irrespective of their opinions on the matter.

3. Tell people where your documents are stored. Give copies to people, including your GP and any professionals treating you. Take them to hospital with you. Make clear that people who know about them must produce them immediately in any medical emergency or if you’re found to lack capacity to make your own decisions (even temporarily). You may need to find ways of engaging with health care professionals who are uncomfortable with being informed about your decisions and may be dismissive or cavalier about your documents (e.g. refusing to look at them and stating airily, “I’m sure it won’t come to that”, in my own experience!).

There may well be other lessons to be learnt from this case – and from another very similar case which I’m currently following in a regional court, in which there are also allegations that P was subject to undue influence in making her Advance Decision to Refuse Treatment.

The case continues after AB’s death

Finally, there have also been two further developments in this case since AB’s death.

One relates to the duration of the reporting restrictions. The family applied to extend the Transparency Order, which prohibits anyone from naming or doing anything likely to identify them, AB and AB’s fiancée, as the people involved in this case. It was due to expire at the end of August 2025. It was extended pending a judicial decision on this, after the family applied for the Transparency Order to be extended for a further 10 years. The family’s application is opposed by AB’s fiancée: she does not want to be subject to a court injunction preventing her from identifying her partner and herself as having been involved in a Court of Protection case. I was joined to that case as an intervenor, and support the fiancée’s position and the principle of open justice.

The other development relates to Poole J’s decision to direct disclosure of Position Statements, and to the very helpful guidelines about disclosure of Position Statements to observers, as set out in his second judgment in this case (Re AB, (Disclosure of Position Statements) [2025] EWCOP 25 (T3)). The family has applied for permission to appeal in the Court of Appeal.

We’ll be reporting on both developments in upcoming blogs.

Celia Kitzinger is co-director of the Open Justice Court of Protection Project. She has observed more than 600 hearings since May 2020 and written more than 100 blog posts. She is on LinkedIn (here), and also on X (@KitzingerCelia) and Bluesky @kitzingercelia.bsky.social)

Footnotes

[1] For previous blog posts about this case see: “Determining the legal status of a ‘Living Will’: Personal reflections on a case before Poole J” and “Validity and applicability of an Advance Decision to Refuse Treatment: A pre-trial review” (both by Celia Kitzinger), and “Preparing for possible future lack of capacity: My advance decision to refuse treatment and the case before Poole J”, by Claire Martin.

[2] Alexis Hearnden and Catherine Dobson, also both of 39 Essex Chambers acted as counsel for the fiancée as well as Victoria Butler-Cole, and all three counsel were instructed through Advocate. All three barristers were representing her because none of them was free for all four days of the hearing (as listed), so they decided to overlap instead, since it wasn’t realistic to expect to be able to find new pro bono counsel who was available for the entire period.

[3] I am grateful to all parties for disclosure of their position statements in relation to this hearing.

[4] Information about the position of the (biological) family is assembled from what was said in court and from the position statements of the other parties and from published judgments. It does not come directly from the family’s position statement since I do not have permission to publish that document.