By Claire Webster, 17th October 2025

Note: On 20-22 October 2025, the UK Supreme Court will be asked to re-visit the question of how to understand a deprivation of liberty. This is the third in our series of blogs about the case. The other two are “Reconsidering Cheshire West in the Supreme Court: Is a gilded cage still a cage?” by Daniel Clark and “Cheshire West Revisited” by Lucy Series.

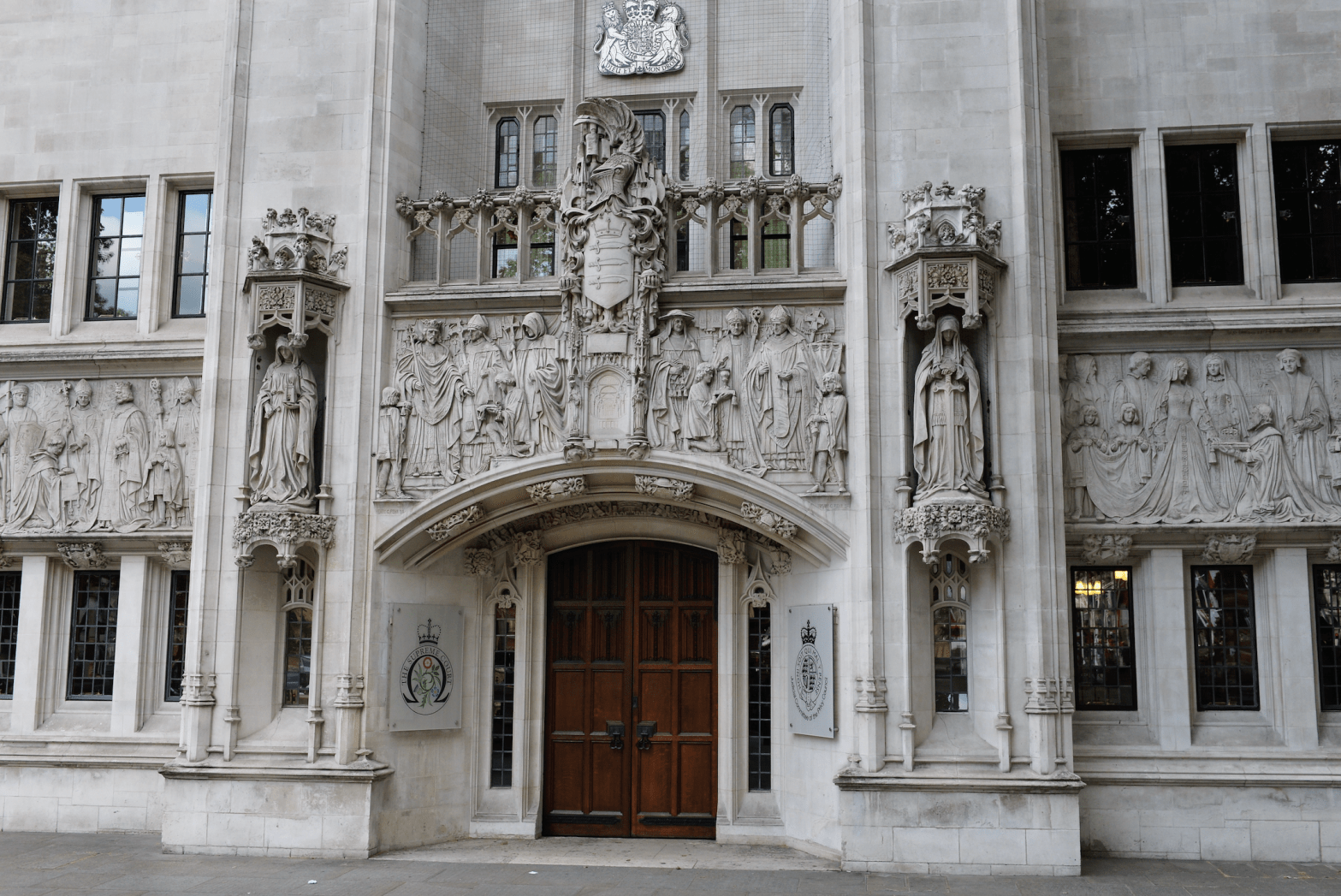

Next week, the Supreme Court will revisit the landmark Cheshire West ruling, and with it, the very meaning of what it is to be “deprived of liberty”.

For those of us working in health and social care, this isn’t just a legal technicality. It’s about real people, real lives, and the systems we rely on to protect them. The two previous blog posts, by Daniel Clark and Lucy Series, have already provided detailed background information.

The case is unusual because it’s not about a specific person or situation, but rather a question of policy: can someone who lacks mental capacity still give valid consent to their care arrangements, simply by appearing content?

This question strikes at the heart of the “subjective element” of deprivation of liberty. And it’s why charities like Mind, Mencap, and the National Autistic Society are sounding the alarm. They warn that changing the interpretation could:

- Strip away essential safeguards,

- Breach the human rights of disabled people,

- And create confusion and inconsistency in protections.

As someone who has worked as a DoLS lead, Best Interests Assessor, and social worker, and now as a Practice Development Consultant at SCIE, I share those concerns.

Compliance is not consent

Drawing on Lucy Series’ points, we must be clear: consent is not the absence of objection. It’s not a smile, or a lack of resistance. It’s not “settling in”. And it certainly isn’t something that should be interpreted by those delivering the restrictions.

If we start treating “happiness” or “contentment” as valid consent, we must ask: Who gets to decide that? The care provider? The commissioner? The person writing the care plan?

Without independent oversight, we risk returning to a system where restrictions go unquestioned, where people’s rights are quietly eroded behind closed doors.

The danger of rushed reform

We’ve been here before. The 2014 Cheshire West ruling rightly expanded the definition of deprivation of liberty, but it came without a roadmap. No rollout. No implementation plan. Just an immediate expectation that practice would change overnight.

The result? A system overwhelmed. Thousands of unauthorised arrangements. SCIE’S analysis shows that 67% of local authorities inspected were found to need improvement in their DoLS processes.

Yes, reform is needed. But reform without support is not progress, it’s peril.

Why independent scrutiny still matters

As a Best Interests Assessor, I met many people who were “settled” in care homes. But when you looked closer, you saw the cracks: relationships restricted; bedtimes dictated; hobbies denied for being “too risky.” These are not small things. They are the fabric of a person’s liberty.

And we must not forget the lessons of the pandemic. When visiting was banned in care homes, 88% of people surveyed said their own or a loved one’s human rights had been undermined. That didn’t happen in a vacuum: it happened in a system without enough scrutiny. (Protecting human rights in care settings)

Reform done right

This case has sparked vital discussion. It’s clear we cannot continue as we are. But change must be thoughtful, supported, and rooted in human rights.

It needs reform not rollback – a phrase inspired by Lucy Series’ blog, who discusses the important role of establishing the existence of ‘volition’ in individuals and recognition of capabilities to genuinely indicate a ‘will’ towards their arrangements:

“The problem with this approach, is who get’s to decide who is happy, and will they do it well?”

But on the objective element:

“…Another Lady Hale dictum: ‘Because of the extreme vulnerability of people like P, MIG and MEG, I believe that we should err on the side of caution in deciding what constitutes a deprivation of liberty in their case.’

We need a system that understands the difference between compliance, consent, and contentment. One that protects liberty not just in law, but in practice.

Because a system without oversight isn’t just flawed, it’s dangerous.

Claire Webster is a Practice Development Consultant for SCIE, specialising in Safeguarding, Mental Capacity, DoLS and Mental Health. She is a qualified social worker and Best Interests assessor, and previous DoLS Lead, with over 20 years of social care experience.