By Jenny Kitzinger, 1st February 2026

Judgment now published here: Cwm Taf Morgannwg University Health Board v RW & Anor [2026] EWCOP 10 (T3) (12 February 2026)

I observed a hearing on 22nd January 2026 before Mrs Justice Theis (COP 20027136). It’s yet another case in which a person appointed as Health and Welfare Attorney has been ignored by doctors making treatment decisions, without regard to the Mental Capacity Act 2005.

It’s remarkably similar to a case I observed a few years ago[1], in which London North West University Healthcare NHS Trust failed to consult the patient’s son and daughter about withdrawal of life-sustaining treatments (including a feeding tube), despite their formal role as Health and Welfare Attorneys, and despite their mother having recorded on the form appointing them: “I want to live and you must fight to help me live. As a Christian, my faith is very important to me…”. In that case, an independent expert appointed by the court subsequently recommended reinstating tube feeding with a view to developing a care package that would enable the patient to spend her remaining time in her own home. Unfortunately, she died before the final hearing. This led to the Trust setting in motion a full Serious Untoward Incident investigation and referring her death to the coroner, as well as apologising to the family. The intention was that lessons would be learned for the future – but if they were, they do not seem to have been shared effectively outside that particular Trust, and as far as I’m aware there is no published judgment.

So now, five years later, Cwm Taf Morgannwg University Health Board has made many of the same errors: an apology has been given to the Health and Welfare attorney in public court, a “Root Cause Analysis” is underway, and the case has already been referred to Care Inspectorate Wales. As in the London North West case, attempts at tube feeding were discontinued (in this case the NG tube wasn’t reinserted after the patient dislodged it). As in the earlier case, the Health and Welfare attorney believed that the patient had not been treated in his best interests. She stated that before he went into hospital he’d been able to eat and drink with support from carers, but since being taken into hospital with a chest infection he had struggled to eat, and the hospital had not sought help from the either her or from the nursing home as to how best to support his nutrition and hydration – and it was this, in her view, that may have contributed to increasing frailty.

A key difference between the two cases is that in this case, tube feeding is now said not to be clinically indicated as the patient is “end of life” and because the risks outweigh the benefits clinically. Neither his Health and Welfare attorney nor the judge can order doctors to provide medical treatment contrary to their clinical judgment – but the attorney believes that it is possible that this “end of life” situation could have been avoided if her role had been recognised sooner, and she’d been consulted about his needs. Another key difference is that the Health and Welfare attorney in this case is not a family member but a professional solicitor, and seemed (unlike the family member attorneys in the earlier case) to have little sense of what the patient’s values and beliefs were or what he would have wanted for himself in this situation.

The judge has asked for further documentation about what happened and will publish a judgment in February 2026 (which we’ll link to from this blog), attempting to determine what went wrong.

This case raises core issues about support for vulnerable patients in hospital, especially around end-of-life care. It also engages with very important, but often ill-defined, questions about decision-making concerning when and whether certain treatments are clinically appropriate and on offer as available options; and, if treatments are available options, the process by which ‘best interests’ decisions are made and who makes those decisions. There are clear legal answers to these questions, but practice is frequently opaque – as this case illustrates.

Background

The protected party Mr RW is in his early seventies, with advanced dementia, plus a significant traumatic brain injury and other health problems. He’s non-verbal, immobile, and entirely dependent on others for all personal care and for nutrition and hydration. There’s no doubt but that he lacks capacity to make decisions about treatment for himself.

He’s been living for some years in a specialist nursing home but became very ill in December 2025, leading to two hospital admissions with aspirational pneumonia: the first on 8th December 2025 and the second on Christmas Eve 2025, when he was also diagnosed with sepsis (due to the aspirational pneumonia) and given IV antibiotics and anti-seizure medication alongside other interventions.

The person with ‘Lasting Power of Attorney’ [LPA] for Health and Welfare for Mr RW is (unusually) not a family member, but a solicitor: Ms Meiner Evans of Endeavour Law[2]. Back in 2020, the local authority introduced Mr RW to this solicitor, as it appeared that he might need support in managing his finances and he had no family or friends to assist him. Mr RW executed a Property and Affairs LPA in favour of Ms Evans in 2020 – and also, crucially, a Health and Welfare LPA. This means that Mr RW appointed her to make decisions for him, in his best interests, when he lacks capacity to make them for himself. (See https://www.gov.uk/power-of-attorney/make-lasting-power).

It was never explicitly stated in court (or in the position statements I’ve been sent) whether or not Meiner Evans has the authority as the patient’s attorney to consent to, or to refuse, life-sustaining treatment: that’s an option on the LPA application form which some – but not all – donors choose. It was a shame that this crucial bit of information (a key thing doctors would need to check on the LPA form) was not clarified in court – but that may be because everyone with the bundle already knew the answer, and didn’t think about the fact that observers did not. It seemed implicit in statements from the LPA herself that her responsibilities do cover life-sustaining treatments (although this was not always how it was framed by the Health Board), but even if Mr RW hadn’t given her authority over life-sustaining treatment decisions, she’d still need to be consulted about them (and would be the decision-maker in relation to consent or refusal of all other treatments on offer). This would put her in the same position as a court-appointed Deputy.[3]

The hearing I observed originated from an urgent application to the Court of Protection by Meinir Evans, which was fast-tracked within three days to the High Court.

Ms Evans has been in touch with the nursing home from the point at which Mr RW was admitted to the hospital (Christmas Eve 2025). She sought a direct update from the hospital on 2nd January 2026 – and several times thereafter. However, she experienced difficulties in getting clear information from the hospital and in getting the hospital to accept and act on the validity of her appointment as LPA, a “communication issue” that the Health Board now recognises was unacceptable.

At the hearing of 19th January 2026 (observed by Celia Kitzinger, who shared her notes with me), counsel for the Health Board acknowledged that the responsible treating clinician was not in contact with Ms Evans until 12th January 2026. The Health Board accepted that delay was “far too long” and “covered an important period”, but added that “We would say, however, that he was admitted with sepsis due to aspirational pneumonia and the focus was trying to get him better”. The judge responded:

“I’ve got that. But if it had been a family member, there would have been communication…. I want to know why there was a breakdown in normal procedures, or if there aren’t normal procedures something needs to be done so this does not happen again. Twelve days is a very long period of time, when decisions are being made, not to involve the deputy.” [4]

It was interesting to hear Mrs Justice Theis assert that “if there had been a family member there would have been communication”. Having spent a long time at the bedside of my severely brain-injured sister (who spent more than a year and a half in hospital), I agree that more communication would have occurred if Mr RW had had family involved. But I also think there is no guarantee that “communication” with family would necessarily have included appropriate consultation (e.g. being asked about the patient’s values, beliefs, wishes and feelings). Nor do I think that family members who hold decision-making positions (as LPAs or Deputies) are always communicated with as they should be – which means not simply being given information, but also being consulted about decisions and being asked to give or refuse consent about some (or sometimes all) treatments on offer. Family members certainly weren’t appropriately consulted in the London North West case where P’s son and daughter were her LPAs (described earlier) – nor was I appropriately consulted about investigations and treatment after I’d become my sister’s court-appointed Health and Welfare Deputy (as I’ll describe later).

Initially, it seems that Ms Evans was given no opportunity to be properly briefed and consulted by the treating clinicians – she couldn’t even get hold of them, and they did not attempt to contact her. She came to have doubts about whether the hospital understood Mr RW’s needs and were treating him appropriately. She became particularly concerned about his hydration and nutrition (attempts had been made to provide this both orally and via a nasogastric tube). She judged it to be in his best interests to be returned to his nursing home as soon as possible, where staff knew him well and had particular skills to support his nutritional intake: this might, she believed, prolong his life, and/or enhance his comfort.

On 14th January 2026, Ms Evans made an urgent application to the Court of Protection for an order that it is “in RW’s best interests to be treated for any reversible conditions in hospital and discharged to [his nursing home] when medically fit for discharge”. She believed that Mr RW had been placed on “an end-of-life pathway” (her phrase at §15 in her position statement of 18th January 2026) and that he might be deteriorating because of insufficient attention to providing him with nutrition and hydration rather than because he was, in fact, ‘terminal’.

During the hearing it became clear that there were disputes of fact and differences of opinion about Mr RW’s clinical state and how he had been, or should have been, treated. But a key issue in this hearing was about the hospital’s failure to consult with the LPA. In the short hearing just a few days before, Mrs Justice Theis had expressed concern about this and asked the parties to submit additional information about communication between the hospital and the LPA. She had also adjourned the hearing for two days to allow time for the planned hospital multi-disciplinary team [MDT] meeting to take place which was going to include the LPA along with representatives from the nursing home. The hearing I observed followed this MDT meeting.

This rest of this blog is in three parts:

First, I outline the hearing I observed and summarise the consensus reached on Mr RW’s future care and the remaining points of difference

Second, I focus on the problems encountered by Meinir Evans in her role as Health and Welfare Attorney for Mr RW and relate it to my own experiences of best interests decision-making as a relative, and subsequently a court-appointed Deputy.

Third, I highlight concerns about the representation, or not, of Mr RW’s own values, beliefs, wishes and feelings over the course of the hearing, and (it seems) in the decision-making process more broadly.

1. Hearing on 22nd January 2026 – consensus and outstanding differences

The applicant was now Cwm Taf Morgannwg University Health Board (replacing the LPA, who made the initial application). The Health Board was represented by Thomas Jones; the LPA, Ms Evans, was represented by Arianna Kelly; the protected party, Mr RW, was unrepresented.

By 22nd January 2026 (the date of the hearing I observed), the MDT meeting had been held and the Health Board was able to inform the court that Mr RW’s immediate care plan had been largely agreed.[5] The parties were all of the view that it was in his best interests to discharge him back to his nursing home. The hospital team was in the process of writing up a community drugs chart, letter to the GP and prescribed deterioration medications.

The major remaining differences between the parties were not about Mr RW’s care – but about three of Ms Evans’ applications:

1.1 Disclosure of documents

Ms Evans wants to be able to disclose the papers and RW’s medical records to the Care Inspectorate Wales, the General Medical Council, the Nursing and Midwifery Council, and Health and Care Professions Council in any related civil proceedings, and any related coronial proceedings. The Health Board’s position is that if Ms Evans wishes to make any complaints, there are separate procedures and jurisdictions for authorising the release of relevant documentation, rather than the current court hearing. Counsel for Ms Evans said that she had yet to decide about all the avenues of complaint, but she clearly wants the option of doing so swiftly and efficiently. The judge said she was keen to avoid the need for any further hearings on this matter and would order disclosure. She asked the parties to try to agree a draft order which ‘ring fences’ the release of documents so they could be provided to the relevant bodies ‘in context’.

1.2 Costs

Ms Evans signalled clearly that, depending on the outcome of investigations, she might well be seeking costs against the Health Board. The Health Board opposed any suggestion that it is liable for any other party’s costs, particularly in circumstances where its evidence is that the LPA’s application had been “premised on inaccurate information”. For example, contrary to the LPA’s claim, the Health Board says that “at no point was any treatment for a reversible condition withdrawn” and the appropriate treatment for his clinical condition had always been continued.

There are also (according to the Health Board) “some conduct issues on the part of Ms Evans. They are relevant if considering costs against the Health Board”.” These “conduct issues” include making the application without following the Pre-Action Protocol, recording telephone calls without informing people, and dealing with others in an “aggressive manner” and not allowing them to answer her.[6]

The LPA challenged this (I think her point was that attempts may have been made to submit the application following correct protocol but this had been difficult given problems with communication with the hospital/Health Board.) Her position was that she would wish to review any evidence filed by the Health Board before reaching a final view on whether or not to make an application for costs – but if Mr RW had been kept in hospital and placed on an “end-of-life pathway” without consultation with her as the LPA, when in fact he’d been medically fit for discharge to his nursing home, she would likely seek costs on an indemnity basis, including pre-issue costs. The judge’s decision on costs will wait until further submissions have been made and will be part of a judgment to be handed down in February 2026.

1.3 Declaration of unlawful (withdrawal of) treatment

The LPA invited the court to make a declaration under s.15(1)(c) Mental Capacity Act 2005 that the withdrawal of nutrition on 8th January 2026 was unlawful. She said: “The hospital appears to accept that these decisions were taken without consultation to the LPA or the care home. This appears to be a clear breach of s.4(7) Mental Capacity Act. Additionally, where the hospital had inserted an NG tube for the purpose of giving artificial nutrition on 6 January 2026, the removal of the NG tube without any other apparent plan to give RW nutrition orally, undertaken without consultation to an LPA known to the hospital and without an application to the court and appears to be contrary to Re Y [2018] UKSC 46, as the LPA was not in agreement with the effective withdrawal of nutrition.” (Position Statement for the LPA, 21st January 2026).

The Health Board completely rejected the suggestion that the (so-called) ‘withdrawal’ of the NG tube was ‘not lawful’. A nasogastric tube was placed on 6th January 2026, but “RW would not tolerate it, kept pulling at his cannula and it was rendered unsafe due to the risk of the tube dislodging, leading to aspiration”. Clinicians came to the view that the risks outweighed the benefits of re-insertion and the Health Board quotes NICE guidelines (NG 97) on tube-feeding dementia patients: “studies found no good evidence that people who had tube feeding lived any longer than people who did not. There was also no good evidence that tube feeding made any difference to people’s weight or improved how well-nourished they were”.

The Health Board position is that it became clear that tube feeding was not a clinically appropriate treatment, so it was no longer on offer as an available option and hence there was no need to consult about it, or to invite the LPA to make a decision about it. The Health Board has also submitted a statement outlining the attempts made by the ward to orally feed RW from 6th January onwards (this was not read out in court or shared with observers).

I did not understand why the question of whether insertion of the nasogastric tube was lawful was not explicitly addressed. It’s a medical treatment that can only be provided if it’s in the person’s best interests – and in this scenario it may well have been the LPA who was the decision-maker (i.e. the person responsible for deciding whether or not inserting an NG tube was in Mr RW’s best interests). Even if she was not the decision-maker herself, it was most definitely necessary for whoever was the decision-maker to consult her (in compliance with s.4(7) Mental Capacity Act 2005). As far as I know, she was not consulted (or even informed at the time), nor was she approached to inform any advance care planning.

This is important, both in relation to Mr RW’s care, and because there are situations where an LPA for someone with severe dementia would want to withhold consent for the placement of an NG tube. They might make a best interests decision to refuse such treatment, for example, informed in part by clinical evidence (such as that cited by the Health Board) and in part by the person’s values, wishes, beliefs and feelings. Although, in this case, the LPA seems to be concerned about withdrawal rather than insertion of the feeding tube this does not change the core principles here i.e. that if a treatment is on offer, it cannot be given to someone unless they consent (if they have capacity) or it is in their best interests (and there is no Advance Decision to refuse it). Without consulting Ms Evans about insertion of the feeding tube, how could the hospital possibly have supported their claim that this intervention was in Mr RW’s best interests?

The judge invited further submissions about the NG tube and the attempts to provide nutrition to Mr RW and her judgment on this issue will be available in a few weeks’ time.

2. Consulting Health and Welfare Attorneys and Deputies – a lacuna in the system?

In discussing Health Board communication (or lack of it) with Ms Evans, the judge made frequent reference to Section 4(7) of the Mental Capacity Act 2005 – which states that the decision-maker must consult appropriately, including with any donee of a lasting power of attorney (s. 7(c)) and person appointed as a deputy (7(d)). She was quite sharp with the barrister for the Trust when he emphasised that Ms Evans had been in touch with the ward and knew some of what was going on. Mrs Justice Theis pointed out that this was insufficient – and highlighted the responsibilities of the clinicians actively to reach out to, and consult, those holding formal decision-making roles. There seemed, she said, to be “a lacuna” in the system.

I was left in little doubt but that between 24th December and 12th of January (almost three weeks) the hospital did not initiate any consultation with Ms Evans – either to collect insights about Mr RW to help them make relevant decisions, or to check whether Ms Evans was in fact the decision-maker in relation to some or all of the treatments on offer.

Ms Evans details her attempts to obtain information about Mr RW’s treatment and describes how she found it inconsistent and was left unclear on key points: “in conversations with UHB [University Health Board] staff, information presented about RW’s care and treatment has often been inconsistent and at times entirely contradictory and it has thus far been difficult to have an entirely clear evidentiary picture of what decisions were taken in respect of RW, when, by whom and why they were taken.” (Position Statement for LPA ,18th January 2026)

Ms Evans also highlighted the difficulties she experienced in trying to obtain appropriate recognition of the fact that she is Mr RW’s ‘health and welfare decision-maker’ – in which role she is entitled to consent to or to refuse treatment that is on offer, acting ‘in his best interests’. The hospital had, she said, displayed “a stark disregard for and misunderstanding of the Mental Capacity Act 2005”: “ME [Meiner Evans] is very concerned that the hospital appears to consider that its only errors were in ‘communication,’ rather than recognising that a failure to consult with people interested in RW’s welfare and who knew him prior to 24 December 2025 was a profound substantive error” (Position Statement for LPA, 21st January 2026).

Ms Evans sent her LPA documentation to the Health Board on 8th December 2025 (during an earlier admission to the hospital on that date). When Mr RW was subsequently admitted again on 24th December 2025, she might reasonably have assumed this information to have been logged in some way. In any case, the fact that RW had an LPA who should be contacted was also conveyed to the hospital by the nursing home on 29th December 2025, and it turned out there was also a written note in a ‘pack’ of information that went into hospital with RW that referred to his supposed wishes around care and the need to “contact [P]’s solicitor regarding any advanced decisions related to his planning”.[7]

Ms Evans subsequently contacted the hospital several times between 2nd and 12th January 2026. But even on 13th January 2026 “the hospital was also very reluctant to accept that ME [Meiner Evans] held RW’s Lasting Power of Attorney. ME spent much of the day at the hospital seeking to confirm that the hospital accepted that she was RW’s health and welfare decision-maker, that she did not agree to his being placed on palliative care, and that her decision was that he should be treated insofar as possible and discharged when medically fit“.

Ms Evan’s account of what happened echoes my own experience of how difficult it can be to ensure that clinicians provide key information to, and consult with, the relevant people. Under the Mental Capacity Act 2005, clinicians are supposed to take into account the views of “anyone engaged in caring for the person or interested in his welfare” (4(7)(b) MCA 2005): this includes people who are ‘just’ family, as well as LPAs and Deputies. I experienced at first hand, first as a sister and then as a Deputy, the devastating effects of a “lacuna” of consultation.

My sister, Polly Kitzinger, suffered catastrophic brain injuries in a car crash in March 2009, in the aftermath of which she had no capacity to make any decisions at all about her medical treatment. Our family encountered what the Health Board’s own investigation (following my official complaint) found to be a series of “significant failings” to comply with the Mental Capacity Act 2005. We were unable to protect Polly from treatment we did not believe was in her best interests, in part because we were not informed or consulted about some medical interventions and, like Ms Evans, we sometimes did not know “when, by whom and why” certain decisions were taken.

The Health Board in our case (Cardiff and Vale UHB) carried out a detailed investigation which concluded that clinicians making treatment decisions about Polly failed to seek out “information regarding [Polly Kitzinger’s] previously expressed wishes, beliefs and values”. The Health Board’s failure to comply with the law also extended to failures to document how decisions had been reached in relation to treatments they had determined to be in Polly ‘best interests’: the response to my complaint acknowledges that the decision-making process had not been documented “either in a care plan or in her medical notes for the majority of treatment and care decisions” (Health Board investigation report, 2011).

It was these failures that led me to apply to become Polly’s Health and Welfare Deputy (an application supported by Polly’s partner, friends, sisters and parents). This was awarded to me on 5th November 2009, about seven months after Polly’s car crash. The Deputyship was for an unlimited period and with the maximum decision-making powers possible under the Mental Capacity Act.

I received the court order just before Polly was moved to a second hospital – a neurorehabilitation specialist centre, within the same Health Board. I was careful to alert everyone involved in Polly’s care to the fact that I was now not ‘just’ Polly’s sister, but also her Health and Welfare Deputy. Polly’s neurorehabilitation consultant was handed the deputyship order in person and I followed up with a formal letter requesting a meeting to discuss how she and I could work together in relation to best interests decision-making. However, it took three months to arrange that meeting and to establish the foundations for appropriate cooperation with my role as deputy. Meanwhile, there was plenty of “communication” with the family, including ‘goal planning’ meetings during which Polly’s clinical team informed the family about their goals for Polly in terms of assessing and trying to stimulate her level of consciousness, for example. But no attempt was made to take into account the Deputy’s role in best interests decisions. Non-compliance with the Mental Capacity Act continued as it had before, despite the “communication”, but now with the added failure in relation to my deputyship. The Health Board’s investigation in response to my complaint found failures “to give prior (and sometimes any) information to the Welfare Deputy regarding several investigations and treatment decisions” and failures “to seek explicit consent for a majority of treatment and care decisions”. The investigators concluded that “These failings highlight a general lack of understanding amongst professionals about the requirements of the Mental Capacity Act 2005…and especially about the role of the Court Appointed Deputy”.

The Health Board responded to these findings by sending me a letter of apology and by developing a 13-point Action Plan – part of which focussed specifically on developing procedures around LPAs and Deputies, including how to keep a record of LPAs/Deputies, how to examine the terms of their appointment and how to ensure that the right people within the Health Board know about the LPA/Deputy and act accordingly.

That investigation was conducted about fifteen years ago, and I kept being told back then that the Mental Capacity Act was still ‘bedding in’. Polly is now in a care home (in a different Health Board area). It’s depressing that I still sometimes encounter health and social care professionals who are ignorant about, or resistant to, my rights and responsibilities as Health and Welfare Deputy and that I still sometimes have to lobby to access relevant information about Polly and ensure that I can deliver on my responsibilities to promote her best interests as her Deputy[8]. It is also profoundly troubling to learn now, in this court case, of problems very similar to those that I faced back then.

The only positive outcome is (yet again) that lessons might be learnt. At the very start of the hearing, the Health Board reiterated its apology to the court and to Mr RW and Ms Evans, and said that they will use a Root Cause Analysis [RCA] to “create focussed learning and service improvements”. I hope any such analysis takes into account the critiques of the RCA model and ensures it does not simply become what the authors of one article in the BMJ Quality and Safety journal refer to as “a procedural ritual, leaving behind a memorial that does little more than allow a claim that something has been done” (‘The problem with root cause analysis‘). I note that one of the strategies highlighted by the BMJ journal authors is to go beyond “disaggregated analysis focused on single organisations and incidents”. So I wonder if Cwm Taf Morgannwg UHB might usefully communicate with other Health Boards (including their neighbour, Cardiff and Vale UHB) which have had to issue similar apologies in the past, developed their own action plans and promised to improve practice.

A large amount of time and thought is often invested in dealing with complaints (most of which never get to court). This includes investment from the LPAs/Deputies involved and from the hard-pressed clinicians whose practice is placed under scrutiny. I hope such learning is shared across health organisations.

3. The patient’s own values, beliefs, wishes and feelings – a lacuna in representation?

The other aspect of this hearing which highlighted problems and might be useful in developing strategies for the future was the lacuna in representing Mr RW’s own voice.

The holistic nature of the best interests analysis was expressed by Lady Hale in Aintree as follows: “The purpose of the best interests test is to consider matters from the patient’s point of view. That is not to say that his wishes must prevail, any more than those of a fully capable patient must prevail. We cannot always have what we want. Nor will it always be possible to ascertain what an incapable patient’s wishes are. …. But insofar as it is possible to ascertain the patient’s wishes and feelings, his beliefs and values or the things which were important to him, it is those which should be taken into account because they are a component in making the choice which is right for him as an individual human being”.

In most Court of Protection hearings I’ve observed, there has been a great deal of focus on the protected parties’ own perspectives – and there’s almost always a litigation friend to represent them. In Mr RW’s case my understanding is that the LPA had liaised with the Official Solicitor who had indicated that she could not act, possibly because of funding issues.

This felt like a significant omission at this hearing and may have contributed to the very limited engagement with Mr RW’s own likely position in relation to many of the relevant decisions. I have seen the Official Solicitor (as litigation friend) work extremely hard to represent P’s voice in court and I’ve been struck by the attention to the details of the person’s current possible experience and actions and I’ve seen the extensive background research that’s sometimes been done. This can include, for example, reviewing GP records and using third party disclosure orders to gain records from agencies which others might not be able to access. I wrote about one such case (also before Mrs Justice Theis) concerning another patient with severe brain injury, and a decision to be made about nutrition and hydration (“The Patient with no friends or family – a challenge for best interests assessment”).

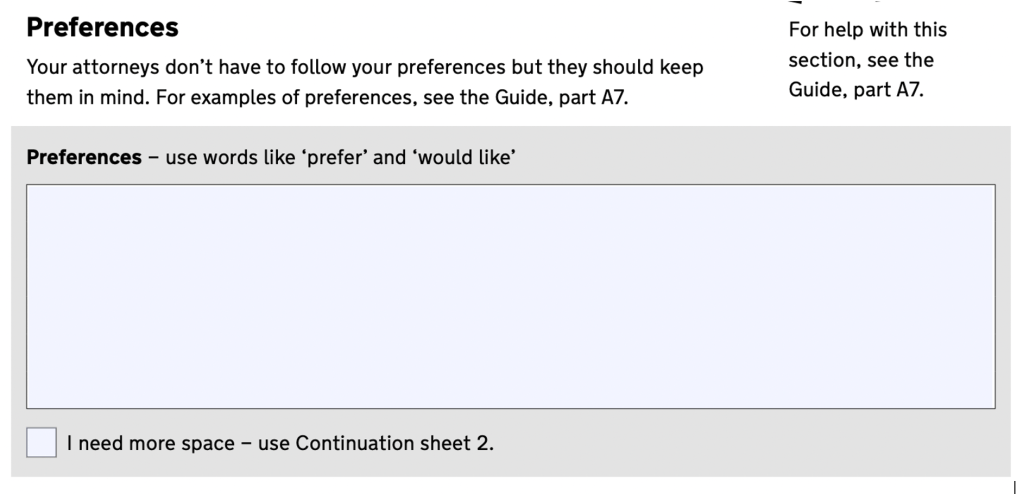

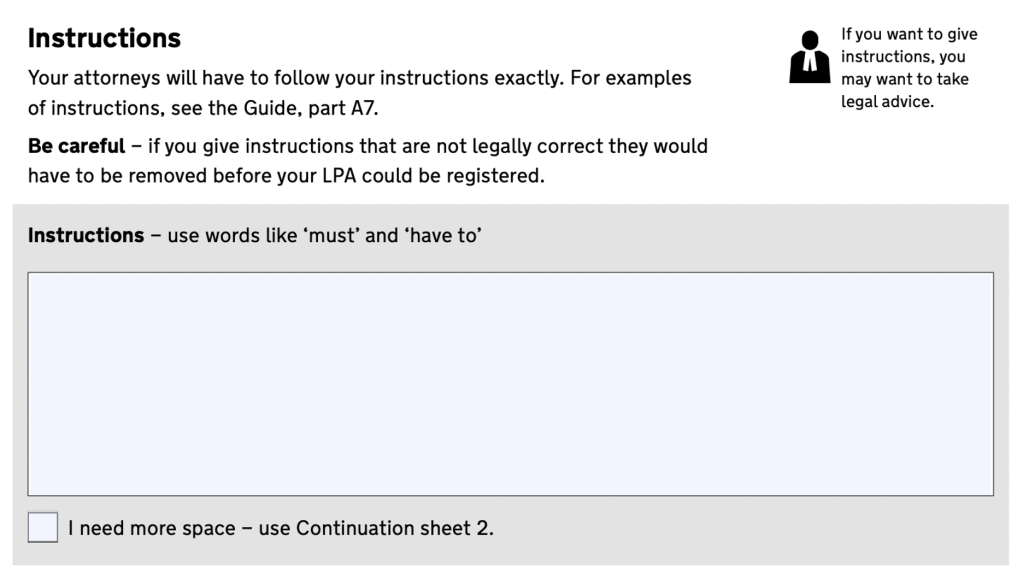

So, it was a surprise to see no representation for Mr RW in this hearing and to learn so little about Mr RW as an individual. I had expected that at least his Health and Welfare Attorney would be able to fill some of this gap, but it seemed very little was known about his wishes – even by her. This left me wanting to know more about what had happened when Mr RW completed the LPA application form to appoint Ms Evans. There’s an opportunity on the form to record ‘preferences’ and ‘instructions’ – this section is, according to another solicitor specialising in LPAs, “the most important part of this form” (“Lasting powers of attorney: Preferences and instructions“). But no reference was made to this section in the hearing and I wonder if it had been left blank.

The one written statement available to the court that purported to represent Mr RW’s wishes was an “Expression of Wishes” dated July 2025. This was brief and was reported as follows: “when he was previously able to communicate his wishes, he expressed that he does not wish to be resuscitated, desires to remain at [the Nursing Home], wishes to be free from pain, and would like to pass away peacefully with dignity and respect.” (Health Board Position Statement, 19th January 2026)

But this record of Mr RW’s wishes was disputed in court by his LPA. She said “The ‘Expression of Wishes’ is not his wishes. He had no ability to do that in 2025”. She’d investigated the provenance of this document and found that it was produced by the care home, and sent to the hospital, as part of a package of information about Mr R. In fact, the care home (according to her position statement) did not consider that it was an expression of his wishes, and it had not been made when he was able to communicate these concepts. This rather begs the question how such a statement could have be produced at all, and it leaves no one any the wiser about what Mr RW’s wishes really were or might have been.

The LPA has not been able to provide anything further about Mr RW’s wishes except that he wanted her to “fight for him”. Counsel for the Health Board said: “[In the MDT on Monday] Ms Evans said she disputed [the ‘Expression of Wishes’] and that he had asked her to ‘fight for him’. But when asked to elaborate on what this meant she had no further information.… Ms Evans does not seem to have a record of his wishes and feelings – she was asked for records of what these might be but she said her records were ‘not available, they are in storage’.”.

If the Health Board’s summary here is accurate, then this is a very unsatisfactory situation. On what basis had the LPA been so confident in disagreeing with “his being placed on palliative care” (as recommended by the hospital clinicians). How was she able to be so assertive in stating that “RW should be treated for any reversible conditions”?

Some people choose not to be treated for reversible conditions, or to forgo interventions where risks and benefits are finely balanced, and some opt to refuse life-prolonging interventions under certain circumstances (e.g. with advanced dementia). They may do this even when clinicians consider treatments to be clinically indicated and in the person’s best interests. What evidence does Ms Evans have that Mr RW would wish to receive treatment for all reversible conditions, given his current quality of life? What evidence does she have that he would NOT wish to be placed on palliative care, as his doctors recommend? It’s hard to see how she is making the relevant best interests decisions with so little to inform her about Mr RW’s past values, wishes, feelings and beliefs.

Very little information about Mr RW’s perspective was available to anyone in this case – not to his Health and Welfare Attorney, and also not to his clinical team, or to the judge. This highlights the need for people being appointed as Health and Welfare Attorneys, especially professionals who are not also members of P’s family or friendship network, to elicit as good a sense as possible of the person’s values, wishes, beliefs and feelings relating to the kinds of decisions that might need to be made in future. These should ideally be supported by a written statement of “preferences”, or “instructions” on the LPA application form, or a separate advance statement and/or advance decision to refuse treatment if the person is willing and able to provide this (and not everyone is!).

My confidence in acting as my sister’s Health and Welfare Deputy relies in part on my ability to bring healthcare information and clinical recommendations into dialogue with what Polly herself might have wanted in the past, or might want now. For example, I am able to think about how Polly might have approached any health and welfare decision because she and I were very close, we debated a lot and Polly was very vocal about many of her values, beliefs, wishes and feelings that turn out to be directly relevant to many of the ‘best interests’ decisions that I’ve had to make since her brain injury. There are also lots of people who knew Polly well who I can consult. Alongside applying to be Polly’s Health and Welfare Deputy, I started inviting written testimonies about Polly’s wishes, I ended up with a dossier of eight letters from her partner, family and friends. This has been an invaluable evidence base and decision-making support tool. I suspect many professional deputies don’t have anything like this.[9]

It must be extremely hard to be involved in complex (and sometimes finely balanced) decisions in the absence of supportive family and friends of P, and without a strong sense of the person’s prior or current wishes to bring to best interests decision-making. In a situation where there is no such scaffolding, perhaps the best thing a professional Health and Welfare Attorney or Deputy can do is to try to ensure that healthcare staff understand P’s physical comfort, communication and support needs (especially when a person is temporarily transferred from nursing home to hospital), and look out for any gaps in good basic care (which seems to have been what Ms Evans has done with great determination and dedication on behalf of Mr RW).

Mr RW (as agreed by all parties and ordered by the judge) should now be back in his nursing home with a palliative care plan prepared. The initial plan is that he will not be returned to hospital except in circumstances where he has a fall, breaks a bone or is otherwise in pain which cannot be managed by the care home. He will not go back into hospital in the event of aspiration or a chest infection. His Health and Welfare Attorney, Ms Evans, will review this plan within one or two weeks based upon his presentation.

For all the parties in this case, it has been a painful, contentious, (and expensive) process to get to this point, and has involved a lot of time pressure and been time-consuming (no doubt taking clinicians away from direct patient care). Between the lacuna in the Health Board’s system and the lacuna in knowledge about Mr RW’s wishes (and without a full picture of what actually went on), it is hard for an outsider to speculate about what was (and is now) in Mr RW’s best interests. But I doubt a contested court hearing between his clinicians and his Health and Welfare Attorney served him well. I suspect this might have been avoided if (a) the hospital clinicians had been proactive and prompt in contacting his LPA as they should have – and if they could have provided her with convincing evidence about how he was being supported to eat and drink and (b) if the Health and Welfare Attorney had been able to produce better documentation of Mr RW’s wishes (e.g. from the ‘instructions’ and ‘preferences’ section of the application) to inform best interests decision-making.

Lessons might be learnt from this case once Mrs Justice Theis has reviewed further submissions and published her judgment. It’s crucial that Health Boards (and Trusts) across England and Wales (and Scotland) pay close attention to this forthcoming judgment to avoid this situation in future – and I hope that the analysis by Cwm Taf Morgannwg UHB will also be widely shared to help improve compliance with the Mental Capacity Act across the NHS.

Jenny Kitzinger is co-director of the Coma & Disorders of Consciousness Research Centre and Emeritus Professor at Cardiff University. She has developed an online training course on law and ethics around PDoC and is on both X and BlueSky as @JennyKitzinger

[1] Three blogs about this case were published: “Health and welfare attorney applies for urgent hearing on life-sustaining treatment”; “Patient dies in hospital as Trust fails to comply with Mental Capacity Act 2005”; and “Reflecting on Re MW and advance planning: Legal frameworks and why they matter”.

[2] I don’t know how many people choose to appoint professional health LPAs – but suspect such appointments are relatively unusual – perhaps especially with authority over life-sustaining treatment decisions. But I can see how a person might choose to do this if they had no one they knew personally who they felt could deliver on this role, or perhaps even wanted a professional LPA to protect themselves against family they actively distrusted. A quick google did locate a number of law firms advertising their services as professional Health and Welfare Attorneys, e.g. saying that a professional attorney will “have those difficult discussions that no one wants to talk about, the ‘what would you want to happen if’ questions…” and will do ‘life-story work’ to get to understand the individual they are acting for.

[3] Attorneys are appointed by the person (while they have capacity to do so), deputies are appointed by the court (for someone who already lacks capacity to appoint an attorney). The specific powers/responsibilities of both attorneys and deputies are as specified in the documentation appointing them, and cannot be determined without inspecting those documents, which may limit/circumscribe their powers in various ways determined by the donor or by the court. A deputy never has authority to refuse life-sustaining treatment whereas someone with lasting power of attorney may have that authority.

[4] According to Celia Kitzinger’s contemporaneous touch-typed notes (from which these extracts are taken), Theis J referred to Ms Evans as ‘deputy’ – rather than ‘attorney’ – at least twice during the hearing of 19th January 2026, but it’s clear from the position statements that Ms Evans is, in fact, the donee of an LPA.

[5] At the beginning of the hearing there remained some questions about CPR and some potential disagreement about ceilings of treatment and whether or not the patient would be returned to hospital under any circumstances, but these were resolved by the parties over the course of a short break during the hearing

[6] Given the way attorneys/deputies are sometimes treated it’s no surprise I think that some end up behaving in ways that seem ‘aggressive’ (as alleged against Ms Evans in this case). When I obtained Polly’s medical notes, I found that (along with other family members who’d been advocating for Polly) I’d had been labelled a ‘difficult’ – “vociferous’, ‘obsessed with the Mental Capacity Act’ and ‘writing letters +++ to the consultant’.

[7]It’s not clear what is meant by “advanced decisions relating to his planning” means of course (and ‘advanced’ is presumably a typo for ‘advance’). Mr RW may have made advance decisions about what Ms Evans “must” do in making decisions about his care (and may also have expressed preferences about what her would prefer her to do or not to do) but if he did this was not conveyed in court. The point, though, is that there was an official record, sent from the care home to the hospital, which refers (albeit ambiguously) to his having a solicitor involved in his care and the need to contact her. This was the last sentence in a paragraph about Mr RW’s wishes. The first part of the paragraph was read out in court. This last sentence was not. (NB A more helpful care home note could have said something like: “Mr RW has appointed Ms Meinir Evans as his Health and Welfare Attorney with the authority over medical decision-making (including/excluding life-sustaining treatment). It is registered with the Office of the Public Guardian and available to view online (access code xxxxxxxxx) here: https://www.gov.uk/view-lasting-power-of-attorney)”.

[8] My official complaint and the incidents described in this blog concern two hospitals in one Health Board, 2009-2010. The Health Board investigation was completed in December 2011. I cannot generalise from this to how things are now, or how they might vary across England and Wales. I now find it is easier to ensure – at least superficial – respect for my deputyship in long term care placements but there is usually an initial settling in-period and I have to working to build understanding with the care home management and GP. I’ve regularly encountered problems early on in new placements, including, for example, finding minutes recording – incorrectly – that my deputyship ‘must’ have run out since I was appointed a long time ago, and finding records with the box ticked claiming there is no deputy or LPA. There also continue to be challenges sometimes when paramedics or hospital staff are involved. From what I hear from other deputies/LPAs, the burden is on us to argue for our position –systems do not always work smoothly to log our existence or to ensure we are appropriately consulted.

[9] What professional LPAs do have, of course, is the knowledge and skills to get a case to the Court of Protection very rapidly – something I lacked at the time when I was trying to get the Health Board to respect my Deputyship and ensure Polly’s best interests.