By Celia Kitzinger, 1 February 2024

The vast majority of hearings in the Court of Protection are open to the public – but almost every day there are also hearings listed as “PRIVATE”.

My decision to take a closer look at “PRIVATE” hearings was made one Autumn day last year when I checked the listings and found almost a third (30%) of the county court hearings in Courtel/CourtServe were labelled “PRIVATE”. Of the 20 hearings listed, there were six “PRIVATE” ones: COP 13367644 in Bristol; COP 13991646 in Chelmsford; COP 14059132 in Pontypridd; COP 13925969 in Southampton; COP 13636214 in Torquay; and COP 14124499 in Worcester.

This didn’t look at all like a court committed to transparency. Had the listings been made in error? What was going on?

I sent enquiries to the different courts concerning each of the six hearings, asking whether it had been correctly listed. I also sent the list of six hearings to a senior service manager in His Majesty’s Courts and Tribunal Service (HMCTS) and asked her: “Are you able to check please whether they really are all private. If so, we are seeing a worrying rise in private hearings. If not, we are seeing a worrying rise in listing errors“. I later heard back: “I have contacted the hubs and they have all confirmed that the 6 cases as mentioned were directed to be heard in private.“ (In fact, the information she received turned out to be wrong: as I explain below, there’s now judicial confirmation that one of the six should have been listed as public.)

I was alarmed to be told that 6/20 county court hearings on this single day (20th September 2023) had been directed to be heard in private. I wanted to find out more about “PRIVATE” hearings – like, how many are there, which judges are holding “PRIVATE” hearings, and why are hearings listed as “PRIVATE”?

I’m told there isn’t any internal audit or routine monitoring of private hearings. Nobody, it seems, can tell me how many hearings are held in private in a given month, or over the course of a year. Nobody can tell me definitively what percentage of hearings are held in private vs. public – or which judges are holding disproprortionately high (or low) numbers of private hearings, or the reasons judges decide to conduct proceedings in private. I am told HMCTS doesn’t have the resources – either in terms of staff or in terms of technology – to audit hearings in this way.

So, I’ve had a go at doing it myself – and I’m concerned about what I’ve discovered.

In summary:

About 10% of hearings are listed as “PRIVATE” – I’ve never again since that day in September 2023 seen as many as 30%.

Only about half of the “PRIVATE’ hearings turn out to have been correctly listed as such. The other half have been incorrectly listed, and should have said they were public (this is of course a concern in its own right). So only about 5% of the total number of hearings are really “PRIVATE” – a much lower percentage than the alarming 30% that prompted my audit, but it still feels like quite a lot of private hearings for a court committed to transparency.

I’ve some concerns that – despite the staff assurances that hearings have been correctly listed as PRIVATE – this might not actually be so. I don’t know how they check this. If all they’re doing is cross-checking an unpublished list against a published list incase there are discrepancies, the finding of no discrepancies doesn’t equate to evidence that a judge actually directed a private hearing. The error may go back further, only to have been reproduced in the unpublished list against which they are checking the information. Some of the responses do refer to judges’ orders – and even quote from them – but even that is open to question (see below).

And then there’s the question of whether the judges who have directed private hearings have done so correctly. I’ve not been able to locate any guidance for judges (or for the public) about the sorts of considerations judges should take into account when weighing up whether or not to make a hearing private. My own experience in the court leads me to think the following questions would be relevant. Has the judge balanced the relevant Article 8 (right to privacy) and Article 10 (right to freedom of information) considerations? Have they considered whether amendments to reporting restrictions (or even a reporting embargo or reporting ban) might enable the public to attend what would otherwise be a private hearing? Have they considered holding part of the hearing in private, but allowing the public to attend the rest – or if it’s necessary for a case to be heard in private for some hearings, could it be in public for others? These are all important questions for open justice.

Of course, it may be that the 5% of hearings I’m told were correctly listed as private have in fact been directed to be heard in private by judges who have anxiously considered the matters I’ve raised above. I just don’t have any evidence to support that.

There are four parts to the rest of this blog post. In Part 1 I’ll give a brief account of how I carried out my audit. Then, in Part 2, I’ll show some of the hearings court staff tell me are correctly listed as PRIVATE and explain my concerns about that. In Part 3, I discuss the hearings that have been incorrectly listed as private when they are actually intended to be public – illustrating with one detailed example some of the time and effort it can take to establish this. I end (Part 4) with some reflections about the way forward.

1. Auditing PRIVATE hearings

Every weekday, lists of Court of Protection hearings are published on public websites: Courtel/CourtServe, the First Avenue House daily hearing list, and the Royal Courts of Justice Daily Cause List. Ideally, to do a systematic audit I would have looked at all these lists every day for (say) a month, each day counting the total number of hearings, identifying those labelled “PRIVATE”, and then writing to the relevant court staff to cross-check with them that the hearing had been correctly so listed.

I didn’t manage anything this systematic, but I did find 30 days from mid-September 2023 onwards when I had time to go through the lists and perform this task. It was time-consuming for many reasons, including having to decide which hearings to exclude from the audit (see below), dealing with the fact that some hearings on the list did not indicate their public/private status at all, and some provided contradictory information (that they were both public and private!). Then HMCTS staff were often too busy to respond to my requests for clarification and I found myself repeatedly and apologetically chasing up my enquiries. So, this isn’t as systematic and definitive an audit as I would like – but I think it’s indicative of what’s going on. And in the absence of HMCTS or anyone else having conducted a better audit, that’s all we have to work with.

A note on the hearings I excluded from my survey. Some Court of Protection hearings are not included in ‘transparency’ guidance and are not intended ever to be heard in public: these are “Dispute Resolution Hearings” (DRH), cases about a person’s property and affairs where there is a dispute between the parties. A DRH is a chance to see whether the dispute can be resolved without needing to go any further. It’s a hearing entirely in private and before a different judge from the one who would hear the case in the future if the case cannot be resolved. There has never been any intention to allow these hearings to be public and the court rules don’t give us the right to observe these hearings. So I didn’t include DRH hearings in my analysis. I also didn’t include “closed” hearings – which are much rarer, and which exclude not only members of the public but also people who are parties to the case (and their legal representatives if they have them). These people (often family members) are generally alleged to have caused harm to P e.g. via abuse, forced marriage, or coercive control (e.g. “Emergency placement order in a closed hearing “; A ‘closed hearing’ to end a ‘closed material’ case). There is judicial guidance saying that “given the very limited circumstances in which a closed hearing can appropriately be ordered, it is very likely to be the case that enabling public access would defeat the purpose of the hearing” (§19). I understand why DRHs and closed hearings are not usually open to the public. It’s all the other “PRIVATE” hearings I’m concerned about – not these. And then there are also hearings in the lists that we can’t observe not because they’re “private” but because there’s nothing to see: e.g. when the judge is making a ruling “on the papers”, or when judgments are handed down in the form of formally releasing a public document. I’ve excluded those as well.

2. “Correctly listed” PRIVATE hearings

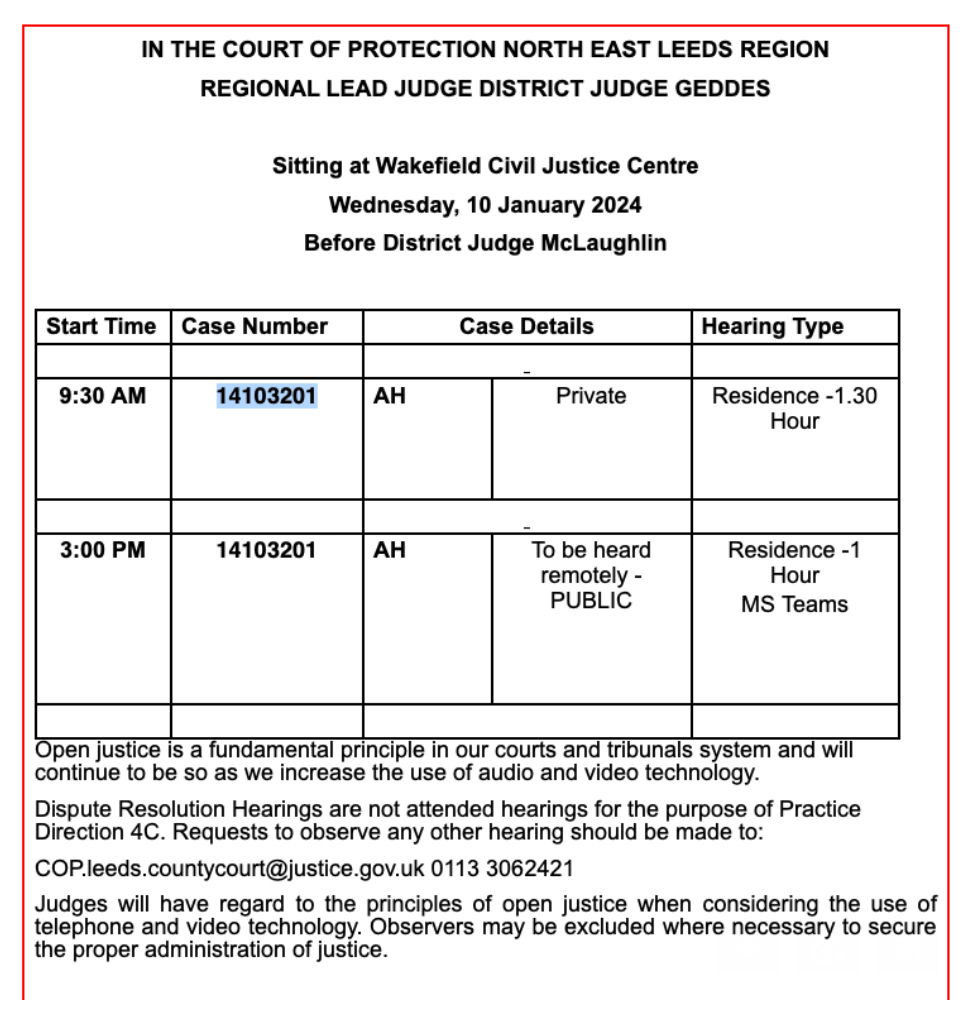

There are lots of hearings that appear marked as “PRIVATE” (and they’re not DRHs or closed hearings), and when I check with the court staff they confirm that yes, it’s been correctly listed. Like these in Bournemouth and Poole, and in Leicester, and the 9.30am hearing in Wakefield.

This one in Bournemouth and Poole says it is “TO BE HEARD IN PRIVATE”. I checked with an administrative officer in Bristol (the regional hub) who confirmed “It is a private hearing“.

This one in Leicester says “Private hearing – Not Open to Public”. I checked with an administrative officer in Birmingham (the Midlands region administrative hub) who confirmed “The matter was correctly listed in private“. There are two more of DJ Mason’s hearings in my data set: COP 13420797 on 13th December 2023, and COP 13783027 on 4th October 2023, both also confirmed as “PRIVATE’ by court staff: so DJ Mason is apparently directing quite a lot of cases to be heard in private.

The 9.30am Wakefield hearing just says “Private”. I checked with an administrative officer in Leeds who confirmed “The matter has been listed correctly as private“.

Sometimes, especially in the Royal Courts of Justice (RCJ), the words “in court as in chambers” are used to convey “this hearing is private”. This is pretty obscure, of course, to most members of the public – who don’t know that’s what this bit of legal jargon means. This RCJ hearing from 10th January 2024 is an example.

I checked this with the RCJ Listing Office, asking “Please can you confirm that this hearing is correctly listed as “in Court as in Chambers” (which I take to mean that it’s private and members of the public can’t observe)” and was told “This matter is to be heard in private“.

Usually the responses I get confirming the accuracy of the listings say nothing more than some variant of “yes it’s correct”. I don’t know what (if anything) the staff did to check that it was correct. A few refer to a judicial order or direction. For example:

- COP 13726955 DJ Taylor (13 November 2023) The staff member quotes this: ““All hearings in this matter shall take place in private and by way of remote hearing pursuant to Court of Protection Rules 2017 r 3.1(2)(d) unless the court directs otherwise.”

- COP 13990303 Rogers J (29 September 2023) “Regarding the listing of the hearing below, as per the Remote Order of District Judge MacCuish dated 14 September 2022, paragraph 1 states the following: ‘All hearings in this matter shall take place in private and by way of remote hearing pursuant to Court of Protection Rules 2017 r 3.1(2)(d) unless the court directs otherwise.’“

- COP 13783027 DJ Mason (4 October 2023) “As per the Judge’s directions, all hearings for the above matter are to take place in private and by way of a remote hearing.”

- COP 13939363 DJ Miles (14 November 2023) “I can confirm that the hearing has correctly been listed as private. The last directions order listing these proceedings reflects that.”

- ·COP 1406338T HHJ Marson (13 December 2023) “In response to your email sent to Leeds County Court of Protection this morning, the courtel list has been done following the direction of the Judge.”

I’m not 100% confident that these responses confirming that the hearings are private by direction of a judge really do reflect a judicial direction in all cases. The first two in particular sound like the standard wording used in transparency orders for private remote hearings introduced in response to the pandemic when courts first moved out of physical courtrooms and onto remote platforms. The proviso was that hearings were private “unless the court directs otherwise“ and the usual practice was that, if a member of the public asked to observe, then the judge would “direct otherwise” without demur. This wording was routinely used prior to statutory changes with the amendments to remote hearings under the Courts Act 2003 and the Remote Observation and Recording (Courts and Tribunals) Regs 2022. Subsequently, there’s been no issue with listing such hearings as PUBLIC, and maybe that’s what these judges should properly have done. But I have no way of knowing for sure without direct communication from the judge.

Even supposing that these judges have anxiously deliberated the Article 8 and Article 10 issues and made carefully considered declarations for private hearings (and the more I think about this the more unlikely I consider it to be), there is no indication of the reasons why these (or any other) hearings are being held in private. Nor is there any indication that if I’m concerned about proceedings being held in private I might have a right to ask for more information or to challenge this. I don’t think I’m entitled to the reasons – although on one occasion which I’ll describe later, they were offered (and proved in fact to be incorrect) – but without them I can’t really do much to challenge a judicial decision.

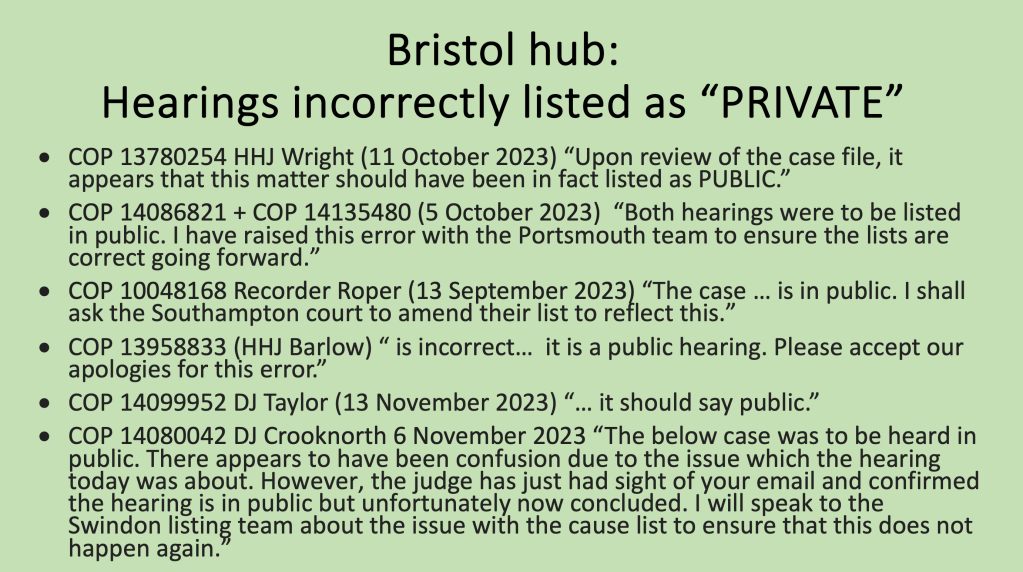

It also seems to me that some of the regional hubs are holding a great many more private hearings than others – amounting to a sort of “postcode lottery” as to whether your hearing will be held in private or in public. For example, I have logged more (confirmed) “PRIVATE” hearings for the Bristol hub than anywhere else – though Birmingham isn’t far behind. (There are also many more “incorrectly listed” private hearings for Bristol than for the other hubs.)

And some individual judges seem to hold more private hearings than others. In the Bristol region that’s HHJ Cronin, DJ Miles, and Recorder Roper KC. In Birmingham, HHJ Plunkett and DJ Mason lead the field. There might be good reasons for this. Maybe they are hearing more cases than anyone else, so have a higher number of “PRIVATE” hearings but the same proportion of them. Maybe these judges are hearing particularly challenging cases with sensitive fact patterns. Maybe they just happened to have hearings listed on days I happened to be checking the listings. I don’t know.

Really, we need someone in the justice system to collect this sort of data systematically and determine whether there’s in fact any inexplicable geographical disparity relating to private hearings and any disparity between judges. There shouldn’t be. That’s not how justice should work.

3. Incorrectly listed public hearings (appearing as PRIVATE when they should appear as PUBLIC)

On any given day, about half of the hearings listed as “PRIVATE” aren’t in fact intended to be private at all. The judge has (I’m told) made no such direction. In response to my enquiries I’m told that these apparently private hearings are actually listing errors.

Here are some examples.

It’s not just Bristol of course. The Birmingham hub has apologised for incorrectly listing hearings as PRIVATE (including COP 14059558, DJ England; COP 13809271, COP 13924116 + 12844123, all DJ Gibson; and COP 13180943, HHJ Clayton). The Manchester hub told me they’d incorrectly listed three hearings before DJ Gray (COP 14005566 + COP 13935068 + COP 13452391) as “PRIVATE” when they should have been public. From Leeds I got an explanation that COP 14125957 before DJ McLaughlin was actually supposed to be public not “PRIVATE” as listed. And First Avenue House incorrectly listed what should have been public hearings before DDJ Chahal (COP 12051835) and – on two separate occasions in December 2023 – before DDJ Atreya (COP 13979630 and COP 1199687).

Event in the (relatively) well-resourced Royal Courts of Justice, hearings are sometimes incorrectly listed – though this is much less common, and this example is from before I started my audit, in May 2023. This hearing before Mr Justice Hayden, which says “in Court as in Chambers” (meaning “PRIVATE”) should have been listed as “in Open Court”.

On enquiry about this hearing before Hayden J (early on the morning that the hearing was due to commence), I was told that it had been incorrectly listed, that actions were in train to correct this, and that I was welcome to join the hearing. The court clerk even sent me the video-link, and other observers also gained access and one of them blogged about the case (“”A lively personality” in a complex medical case“).

All these incorrectly listed apparently PRIVATE hearings are a public relations disaster for a court concerned to display itself as open and transparent. They double the number of hearings that appear to be private on the listings, and they have the practical effect of making public hearings into private one – because including the word “PRIVATE” on a court listing obviously dramatically reduces the likelihood of a member of the public asking to observe it.

Lawyers I’ve shared my data with have expressed surprise that so many hearings are listed as private. They tell me they’ve not been involved in private hearings very much at all, not for ages, not ever, they’re very rare. Presumably this is because they don’t know that the hearings they’re involved in, which they know to be “public” (because they have the transparency order in the bundle) are de facto actually “private” because that’s how they’ve been listed.

I don’t think the incorrect listings are part of a conspiracy to exclude us. They often have that effect of course, because we don’t find out they’ve been incorrectly listed until after they’re over. But I accept the explanations I’ve been given that these incorrect listings are as a result of “oversight“, “internal error“, “confusion“, and (often) “identify a training need“. I have alerted my HMCTS contacts and they tell me they are now addressing this.

One example of how a public hearing came to be incorrectly listed – and the work it took to establish this

Here’s an example of how this “confusion” manifested itself in one case – and I’m very grateful to the judges concerned for taking the trouble to root out the problem. I suspect this sort of problem (and others like it) is far more common than is widely acknowledged, but it takes judicial commitment to open justice to track down the issues.

On 20th September 2023, the fateful day that launched my auditing exercise, one of the 6 “PRIVATE” hearings was COP 13991646 before DJ Molineaux, sitting in Chelmsford. On that day, staff from all six hearings got back to me – and to the HMCTS senior service manager I was in contact with – to say that all six hearings were correctly listed as PRIVATE. The hearing before DJ Molineaux was no exception. I logged it (as did the service manager) as a correctly listed PRIVATE hearing.

But things didn’t end there. The email I received confirming that the hearing was PRIVATE was unusual in giving a reason for this decision: “This matter was listed in private for all hearings as directed by the Judge as Protected Party is a minor.”

This surprised me because I’ve observed a lot of COP hearings before and since concerning protected parties who are minors, and we’ve blogged some of them (e.g. Moving towards transition from children’s to adult services” ). I checked with some lawyers and was told “there’s nothing in any of the transparency stuff which draws a differentiation between those below or above 18, which suggests that there has not intended to be any difference in such cases“. So I wrote to the judge (forwarding the email claiming that the hearing was private because the protected party was a minor) and pointing out that “I appreciate there may be other reasons for deciding to hear this case in private, but am concerned that the reason given … is not sufficient“.

My email was passed to the lead judge for the region, HHJ Owens, who took the time to relay a response back to me. She was clear that simply because a child was involved was not a reason for a decision to be taken that COP proceedings would be held in private, but that in this particular case that there had been an initial direction for the proceedings to be in private because it appeared that there were or had been linked Children Act proceedings, and Section 97 of the Children Act 1989 makes it a criminal offence to publish any details that would lead to the identification of a child involved in such proceedings. There were also concerns (she said) about abruptly removing the protection of privacy guaranteed in the previous jurisdiction as the child moves into the COP, such that time was needed to consider welfare matters related to this. This all sounded appropriate to me, and I was reassured to know that the declaration requiring a private hearing had been properly considered.

Then, about an hour later the same day, I got another message from HHJ Owens, who had now liaised with DJ Molineaux (so two judges were involved in sorting this out). She told me that “the proceedings were in fact directed to be in public subject to a transparency injunction following review by the allocated judge quite some time ago, but there seems to have been an uncorrected typo on an order issued in August this year which referred to the proceedings being in private because they were remote“. The advocates, she said, were using an old template.

So COP 13991646 turned out to be not – as I had previously been told (twice!) – a correctly listed private hearing, but an incorrectly listed public hearing.

Just a note for the conspiracy theorists out there – there was no cover-up! I believe that the court staff who told me (and their senior service manager) that the hearing was private were reporting accurately what they – falsely as it turned out – believed to be the case. I believe that in her first email to me, HHJ Owens also told me what she believed to be true. And if there had been any conspiracy to keep the hearing secret, she need never have sent me that second email, correcting her earlier statement that the hearing was private. The judicial candour, and the time and commitment it took to investigate this matter, is very reassuring. The error, of course, is not!

4. Reflections on the way forward

The judicial aspiration to transparency is obviously not met when there are private hearings. Of course sometimes transparency has to give way to other compelling human rights considerations. But that’s not what I’m seeing here. I’m seeing a mess – with lots of hearings wrongly listed as PRIVATE when they shouldn’t be.

I don’t want to deny or underestimate the huge progress the Court of Protection has made towards transparency in the last decade. Until the end of January 2016, all COP hearings (with very few exceptions – notably serious medical cases and committal hearings) were heard in private. That was the general rule, the default position. This was effectively reversed with the introduction of the Transparency Pilot (subsequently incorporated into normal COP procedure) in January 2016, which made the vast majority of hearings public with reporting restrictions – and this became the newly established default position. At the beginning of the pandemic, when hearings moved out of physical courtrooms to telephone and video hearings, the (then) Vice President, Mr Justice Hayden, made transparency one of his priorities. Unfortunately, the Coronavirus Act 2020 did not extend to the Court of Protection the broadcasting rights afforded to other courts. This meant that remote Court of Protection hearings had to be labelled PRIVATE, but the Vice President’s guidance said that this was with the proviso that if a member of the public (or journalist) asked to observe a hearing, then “active consideration” must be given as to how to acheive this. And in practice, we were regularly admitted to hearings labelled private: the Open Justice Court of Protection Project was set up towards the beginning of the pandemic (June 2020) and has published hundreds of blogs about the hearings we watched over the next two years. The frustration we faced, given that the public were regularly admitted to “private” hearings back then, was the deterrent effect the label had on members of the public who - perfectly reasonably! – didn’t understand that “PRIVATE” didn’t mean we couldn’t attend. (See my detailed discussion of the state of play regarding “private’ hearings up until June 2022 in my blog post for the Transparency Project here: “”Why are so many Court of Protection hearings labelled ‘Private’?”).

The situation now is different. Everything changed with the amendments to remote hearings under the Courts Act 2003 and the Remote Observation and Recording (Courts and Tribunals) Regs 2022. Court of Protection hearings can now be listed as PUBLIC without falling foul of any statutory provisions. So when they say PRIVATE, it’s reasonable to believe that private means private. Which is why it’s disturbing to find that at least 50% of the time, it doesn’t. And I really don’t know what’s going on the other 50% of the time, but I’m not fully convinced that private really means private then either – or that it should do. The one and only occasion that the judiciary launched (at my instigation) a proper investigation into why a hearing had been labelled private, eventually yielded the discomforting outcome that an “uncorrected typo” had resulted in a public hearing being incorrectly listed.

I’m only a public observer. I don’t have the powers to investigate the problems, or what is causing them, or how they might be sorted. What I can do is point out something of the extent of the problems and ask HMCTS, lawyers and judges to do something about them.

I’m sure there’s a training need (there always is) and I’m sure someone will tell me about a new system or snazzy computer fix which will make everything better. Maybe.

This really needs a systems-level solution. But one simple change you could all make right now is to check how your hearings are listed in CourtServe (or First Avenue House or on the RCJ website) the afternoon before the day of your hearing (and get them corrected if they’re wrong). Because that’s what we’re looking at when we’re thinking about observing a hearing, and what we see there will determine whether or not we believe your hearing to be open to us to observe. And if it says PRIVATE, we probably won’t try to come along and observe it.

Celia Kitzinger is co-director of the Open Justice Court of Protection Project. She has observed more than 500 hearings since May 2020 and written more than 100 blog posts. She is on LinkedIn (here), and tweets @KitzingerCelia

I am concerned about private hearings status not only keeping out public scrutiny but also the excluded Ps whom some LAs consider not needing to know and they may oppose some aspects of the submissions made. LAs don’t communicate with Ps out in the community and it’s a miracle the Ps know anything about the LAs plans for them.

LikeLike

Dear Joan – Thank you for contributing to our blog with this comment. I’m also concerned that P doesn’t not always know what is happening in the court cases about them and we’ve published some reports that P’s wishes and feelings are not the same as the argument advanced by “their” barrister (appointed via the Official Solicitor to represent their best interests). However, a “private” hearing means only that members of the public (and journalists) cannot attend. It has no bearing on whether or not P can or does attend. In fact, one hearing I tried to attend was initially “Public” but P was there and said she would not feel comfortable and would leave her own hearing if members of the public were to remain. The judge made the hearing “Private” on that occasion – and I think that was the right thing to do. (Celia)

LikeLike