By Amanda Hill, 6th August 2024

This is a blog about an application to change (“vary”) a Transparency Order, the order restricting what can be reported from a Court of Protection hearing.

Unlike many other blog posts about applications to change Transparency Orders, the application this time isn’t from a member of the Open Justice Court of Protection Project (OJCOPP) team.

It’s from a family member of the protected party (P) who wants to be able to tell people – especially people going through it – about her experience of Court of Protection proceedings, both as a family member and as a litigant in person.

The substantive proceedings are virtually over, and she’s content with the outcome for P.

But she’s found the whole process incredibly stressful, and she wants to be able to offer support to other people in a similar situation from the perspective of someone who knows what it’s like from the inside.

The application is not proving straightforward. At the hearing I observed (COP 14106873, on 27th June 2024 before District Judge Bridger), the judge postponed making a decision. It will come back to court in a few weeks’ time – and Celia Kitzinger (who also attended the hearing I’m reporting on) will act as an “Intervenor” , as she did in another case reported here: When families want to tell their story: Discharging a transparency order. An intervenor is someone who is not a party to a case but a person who may be affected by its outcome and the judge therefore grants them permission to join ongoing proceedings.

There are many families who want to speak out about their experience of the court but are prohibited from doing so by a court order (e.g. Gagged – in whose best interests?). It’s an important issue for open justice.

Background to this hearing

It’s a common story I’ve heard many times before in Court of Protection proceedings. You’re a close family member of a young person with a learning disability. You have loved, cared for and supported her since her birth. You have watched her growing up. She turns 18 and in the eyes of the law becomes an adult. You carry on supporting her as she moves towards independence and into supported living. Then there’s a dispute about where she lives, and suddenly the state intervenes. The Court of Protection becomes involved, she becomes a “protected party” and a judge becomes responsible for making certain decisions about her. Not you. You have to learn about the Court of Protection and navigate your way around the legal processes.

You find it incredibly difficult but you want some good to come from your experience. You want to share your story with other families, so that they feel less alone, and so that they can learn from what you went through. But you can’t, because as part of the Court of Protection’s processes, and in order to protect the privacy of the person at the centre of the case – the “protected party” (P), you are subject to a Transparency Order that means you will be in contempt of court if you even reveal that you are the relative of a P in the Court of Protection. You almost certainly didn’t understand this at the beginning of the proceedings when there was a barrage of legal documentation. Now you want the transparency order to be changed so that you can speak out in your own name about your experience. And it is a Court of Protection judge who will make that decision.

I don’t know all the details about this particular case. I’ve only observed one hearing and although it was listed as being “A review hearing re P’s placement, and contact”, the parties had all agreed on those outcomes (which was good news) so the application to vary the transparency order was the main remaining issue.

I will now focus on three points. First, “Transparency orders and how they impact families”, to set out the context for this case. Second, “Recurrent mistakes in Transparency Orders”, which describes two errors made in this case – both of which are common in my experience. Finally, “Speaking out” which addresses what actually happened in the hearing in relation to the application to vary the transparency order – the central issue of concern to any family member who wants to be able to talk about and report on their experience of the court.

Transparency orders and how they impact families

Families involved in Court of Protection cases are routinely subject to transparency orders (a form of injunction) which mean that they aren’t allowed to tell anyone about the court proceedings. The OJCOPP has reported on a few cases where families gained court permission to name themselves and ‘P’, the protected party – e.g. Laura Wareham (The point is this – she is scared and vulnerable’: Judge about Laura Wareham) and William Verden (After the kidney transplant: The view from “Team William”) – but those are the exceptions, not the rule.

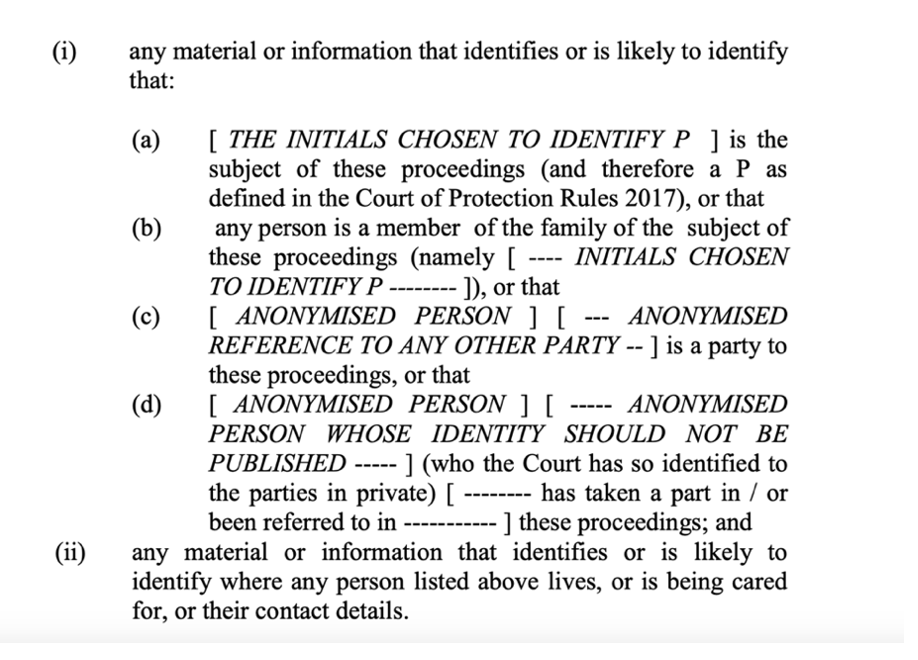

The order served on families (and everyone else involved in the court proceedings, and all observers) is based on the “standard” transparency order template which is here: https://www.judiciary.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/cop-transparency-template-order-for-2017-rules.pdf

Paragraph 6 of the standard template outlines the subject matter (the “material and information”) covered by the transparency order which is:

So typically the injunction means, as outlined in (i) above, that P can’t be identified as a protected party (“P”) in the Court and so (in order to protect P’s identity) neither can P’s family members, or any other parties as specified in ( c ) or any other person specified in (d) (this often lists people who’ve been in court to give evidence, e.g. a manager of a care home, or a social worker, or clinicians treating P in a hospital). Part (ii) of § 6 is intended to ensure that where P and the other specified people live can’t be identified.

Occasionally transparency orders have a specific end-date or an ending specified with reference to a particular event (e.g. P’s death or the birth of P’s baby). But often the order states that restrictions remain in place “until further order of the court” (§8). This means that an order is in place indefinitely and a family member has to make an application if they want the order discharged (or varied).

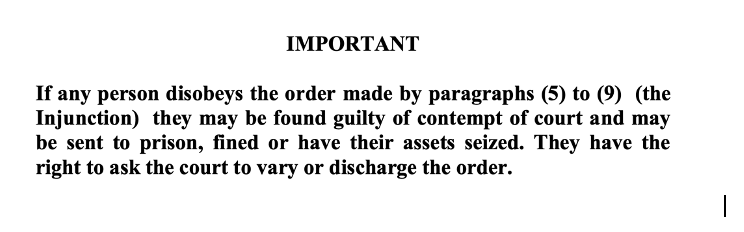

What happens if a family member disobeys the order? It can have very serious consequences. It is clearly stated on the face of the transparency order:

If anybody breaches this injunction, they could face “committal hearings”: the judge could them to prison. This does sometimes happen and OJCOPP blogs have covered this type of hearing. Here are two examples:

- DB was parking his car near EB’s previous placement with Court of Protection documents visible through its windows, so he was identifying P to anyone who looked through into his car – and understood what they were looking at – as a P in the Court of Protection. (“Committal hearing: Struck out and dismissed for procedural defects”)

- A mother, Luba McPherson, has breached the order by putting up videos and images of her daughter on social media to draw attention to the injustice she says she and her daughter experience in the court (“Committal hearings and open justice in the Court of Protection “)

For more than a decade, though, it’s been recognised that it may not always be appropriate to prohibit families from speaking out about their experience in the Court of Protection: “for example, where family members wish to discuss their experiences in public, identifying themselves and making use of the judgment” (§11). (“Transparency in the Court of Protection, Sir James Mumby, then-President of the Court of Protection).

Although there have been some cases where transparency orders have been varied or discharged to allow P to be named while they are still alive (like William Verden and Laura Wareham), it’s usually easier to get transparency orders discharged after P has died, as once somebody has died, they no longer have Article 8 rights to privacy.

After her father died, Carolyn Stephens wanted to tell her story publicly, to warn people about the potential for “dangerous abuse” of Lasting Power of Attorney legislation. Based on what happened to her father, she believes there should be more safeguards to protect vulnerable people. She was able to tell her story, under her own name, in the Daily Mail after the judge approved her application to discharge the TO (see “When families want to tell their story: Discharging a transparency order”). The judgment sets out the reasons why the judge discharged the transparency order: In the Matter of VS (deceased) [2024] EWCOP 6

The situation at this hearing I observed is different from Carolyn Stephens’ case because P is very much alive – and so still has privacy rights that need to be protected by the court. The challenge facing the court is to balance P’s Article 8 right to privacy with her family member’s Article 10 right to freedom of speech and the public’s right to hear about her experience.

Recurrent mistakes in Transparency Orders

There are often mistakes in transparency orders, even after they’ve been approved by judges and “sealed” (stamped with an official mark to indicated that they’ve been issued by the court). (Check out “Anxious scrutiny or boilerplate?”).

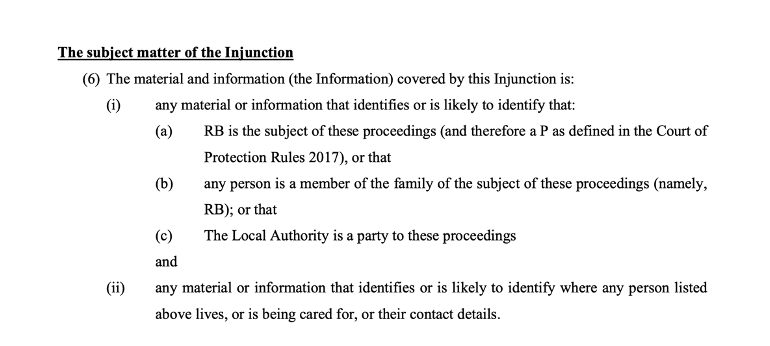

The TO in this hearing had two mistakes: (a) it prohibited identification of a public body and (b) it included private information in the (public) transparency order.

(a) Prohibiting identification of public bodies

Generally, there is no reason why the identity of a public body should not be revealed – either in judgments or in public reporting. According to the court’s own Practice Direction:

“The aim should be to protect P rather than to confer anonymity on other individuals or organisations. However, the order may include restrictions on identifying or approaching specified family members, carers, doctors or organisations or other persons as the court directs in cases where the absence of such restriction is likely to prejudice their ability to care for P, or where identification of such persons might lead to identification of P and defeat the purpose of the order.” (s 27 of Practice Direction 4A Hearings (Including Reporting Restrictions)

As one blogger, Daniel Clark, says: “It’s important that we can talk about the involvement of public bodies in Court of Protection cases. After all, they’re funded by taxpayers and therefore accountable to the public. If they act in secret, their actions cannot properly be said to be open to scrutiny” (“Prohibitive transparency orders“)

But it keeps happening. The Project has posted a lot of blogs about this recurrent problem (e.g. “Getting it right first time around”: How members of the public contribute to the judicial “learning experience” about transparency orders; Challenging a Transparency Order prohibiting identification of the Public Guardian as a party; Bournemouth, Christchurch and Poole Council named as “secret” body in restraint case; Varying reporting restrictions to name Kent County Council in “shocking” delay case).

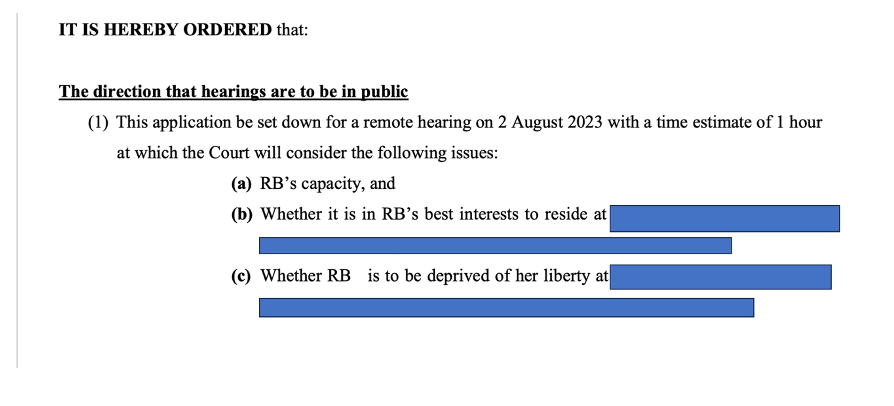

When I was sent the transparency order (TO) for this case (made by a different judge about a year earlier), I immediately noticed the wording in §6(i)(c):

Paragraph 6(i)(c) states that no material can be published that identifies or is likely to identify the local authority in this case. This reporting restriction should not be made without very good reason (e.g. because the case is so unusual that knowing the name of the local authority would risk people becoming able to identify P).

Prior the start of the hearing, Celia Kitzinger had sent a letter asking for this restriction to be removed from the TO. The judge came to this request fairly early on in the hearing. He asked Zoë Whittington (Counsel for the Local Authority (LA), Wokingham Borough Council, the applicant in this case) if there was any objection to removing the clause prohibiting the naming of the LA. Zoë Whittington stated that it wasn’t the intention to anonymise the LA. The judge then said “It’s in the current transparency order”. She seemed surprised and took a short time to check. She then told the judge that he was correct and restated “I don’t think that was necessarily the intention”. The judge then asked “Are we agreed that the LA not being named can be agreed” and Zoë Whittington agreed that it could (and nobody else objected). The clause prohibiting the local authority, had seemingly been included in error and not been picked up for nearly a year.

It’s unfortunate that this error had been made and left uncorrected for almost a year. It’s also unfortunate court time needed to be used to fix this error, and that the court relied on a member of the public to pick up the error in its own legal document.

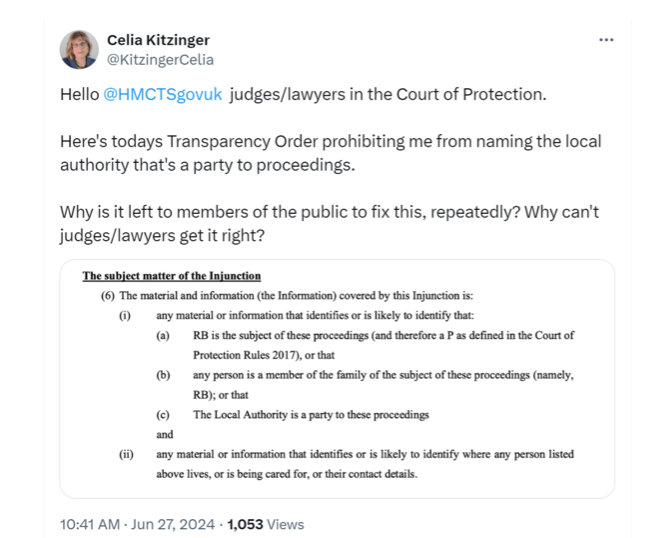

It’s clear that Celia Kitzinger – who frequently raises this problem with the court – is pretty exasperated by this recurrent mistake. After the hearing she tweeted this:

As always when members of OJCOPP points out this error, other members of the public react to it by expressing the view that this is evidence of a cover-up – that the court is keeping things secret to cover up illegal or immoral activities (as the responses to this tweet illustrate). This mistake has very negative consequences for the reputation of the court. There is often an assumption that it’s conspiracy rather than cock-up and OJCOPP has to work hard to counter this impression.

(b) Including private information in the (public) transparency order

The purpose of transparency orders for observers like me is so that we know what we are allowed to publish.

Although the names of individuals and where they live might be revealed to the public during the course of a hearing, the transparency order almost always makes it clear that this information is covered by the injunction and should not be reported. Such information is not supposed to be included in the order itself.

In 2017, Mr Justice Charles (the then Vice President of the Court of Protection) published a note about the Transparency Pilot (triggered by a judgment he’d just handed down). He updated the standard TO and it’s clear that TOs should be in an anonymised form.

Here is a screenshot of the standard TO attached to his note:

It clearly states that P should be identified by initials.

This second screen shot of the standard TO attached to Mr Justice Charles’ note shows that parties should be anonymised:

Including P’s address as part of the TO doesn’t seem to be compatible with the spirit of this standard TO. In addition, Practice Direction 4C states (at s2.3) that, “An order pursuant to paragraph 2.1 will ordinarily be in the terms of the standard order approved by the President of the Court of Protection and published on the judicial website” i.e. it should be anonymous.

Finally, s14.26 of the CoP Handbook (which I understand is guidance rather than binding like a Practice Direction) notes that “The Transparency Order is a public document and therefore P’s full name should no longer appear in full in it. Likewise the names of the parties should be ‘appropriately anonymised’; although as with judgments public bodies should be named in full.” It seems to be a fair inference, therefore, that a TO should not include P’s address.

In practice, it’s not unusual for observers to be given confidential material when we’re sent the order. Sometimes P’s name is in the body or on the face of the order. Sometimes it’s in the file name. I once observed a hearing where the transparency order prohibited reporting that the other parties were the parents of P and their identification, but a ‘confidential’ annex named them.

The transparency order that I was sent for this hearing contained P’s full address. It looked like this, (I’ve blocked out the identifying details):

This had the effect of breaching her privacy, the very thing that the court is supposed to be protecting.

Once again it was Celia Kitzinger who identified the problem, alerted the judge to it, and asked for the order to be amended. The transparency order dates from July 2023 – so that’s nearly a full year that anyone who has been issued with the transparency order has been provided with a printed or electronic document with full details about where P lives.

The court seemed surprised and shocked by the address being included in the transparency order. Although the judge remarked that not many people would have seen the TO (I got the impression there had not previously been observers in this case), he accepted that P’s address “shouldn’t have gone in” and that the TO should be varied to remove it.

Speaking out

Despite the technical failings of the TO in this case, it does correctly and competently do what it is designed to do – which is to prevent P’s family members from being publicly identified as the relatives of a P. And this means that it prevents them from telling the story of their Court of Protection experience in their own name.

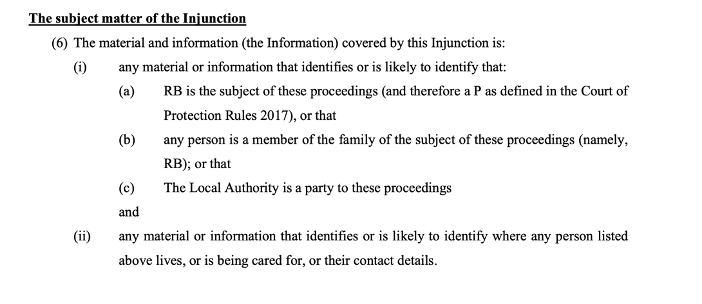

Paragraph 6 defines the “Information” that the injunction is about. That information is the identity of the person at the centre of the case ((6)(i)(a)) and her family members ((6)(i)(b) and the LA, and any information about where they live. Then paragraph 7 of the transparency order, says that the information listed in §6 “cannot be published or communicated by any means orally or in writing, electronically, and persons bounds cannot cause, enable, assist or encourage the publication or communication of it or any part of it”.

The effect is that no family member of P can tell anyone that they have a relative who is a protected party in the COP – not in conversation with them, not in writing, not via social media or in any other way.

The use of the word “family” in this part of the TO is not a “mistake” because it is exactly as used in the ‘standard’ template provided in the Practice Direction. But it can and does cause problems. Who exactly is covered by “family”, and how far that stretches, has been raised recently in the case involving Carolyn Stephens mentioned earlier in this blog. In that case there was a dispute about whether or not one of the parties (the daughter of the companion P met late in life) was or was not “family”. According to Celia Kitzinger “the transparency order was poorly drafted in not listing the specific members of the “family” whose identity it was intended to protect. This should be remedied in future orders, especially in situations in which unmarried partners, step-families and “blended families” are involved.” However, this issue was not resolved by the judgment. Senior Judge Hilder wrote (§23): “I consider that it is not necessary for me today to make any finding as to whether Dr Sorensen falls within a legal definition of “family”. I can see many circumstnces in which this might become an issue. “Family” is a wide ranging term – is it restricted to the close family of P – parents and siblings? What about cousins? Or grandparents? Step-children? Civil partners? Is there actually a legal definition of what the term ‘family’ used in the TO means? I haven’t been able to find one.

The focus of this hearing (given that the issue of residence and contact had been agreed by the parties) was one family member’s application to vary the TO – on which it turned out there was a disagreement.

The problem was that the judge had only received the documentation from the Local Authority and the Official Solicitor (P’s litigation friend, represented by Rachel Sullivan ) in the hour before the hearing. And because he had been in another hearing, he hadn’t had time to read them properly. Neither had P’s two family members who are parties in the case. (Nor, of course, had Celia since she hadn’t yet been appointed as an Intervenor.) The documents the judge hadn’t had time to read included the position statements, which outlined the parties’ positions on matters to be discussed in the hearing, including most especially the matter of varying the Transparency Order.

It is obviously of vital importance that the judge and all the parties have had enough time to read and assimilate the information before the hearing. The judge made it clear that more time was needed and that he was going to adjourn the matter for another hearing. He said he would approve the draft final order concerning residence and care (bringing to an end the substantive issue the case was concerned with). He also appointed Celia Kitzinger, at her request, as an intervenor in the case.

There was a very interesting exchange before the hearing was adjourned. The judge had alluded earlier in the hearing to something he wanted to raise (“One other thing that slightly bothers me”) and he returned to it now. Addressing the party who wanted to be able to speak publicly about her role as a family member of P in the COP, he said he wanted to flag up his concern that P was “quite a vulnerable young lady (because of her learning disability) and the court will want to protect her privacy”. He was concerned that allowing a family member of P to identify herself as such would increase the risk of P’s identity and where she lives being known, and that she would be exposed to “undesirable” characters. “Somebody could track her down” and “it makes her vulnerable”. The judge summarised: “Those are my concerns…..to keep her away from undesirable people, she’s open to suggestion…”.

He asked the applicant (the family member applying for variation to the transparency order) if she wanted to say anything at that point. She replied that she accepted the judge’s concerns but that P was always with a member of staff or with family and “is never left on her own”.

The judge was highlighting this concern so that the parties knew his preliminary thoughts and could address those concerns in their position statements to be submitted in advance of the next hearing , which is likely to be in September.

I hope to observe that next hearing so that I can find out what the judge’s decision will be.

Amanda Hill is a PhD student at the School of Journalism, Media and Culture at Cardiff University. Her research focuses on the Court of Protection, exploring family experiences, media representations and social media activism. She is on X as @AmandaAPHill and she is on LinkedIn here

.

One thought on “She wants to tell her Court of Protection story but will the court allow her? ”