By Georgina Baidoun, 4th October 2024

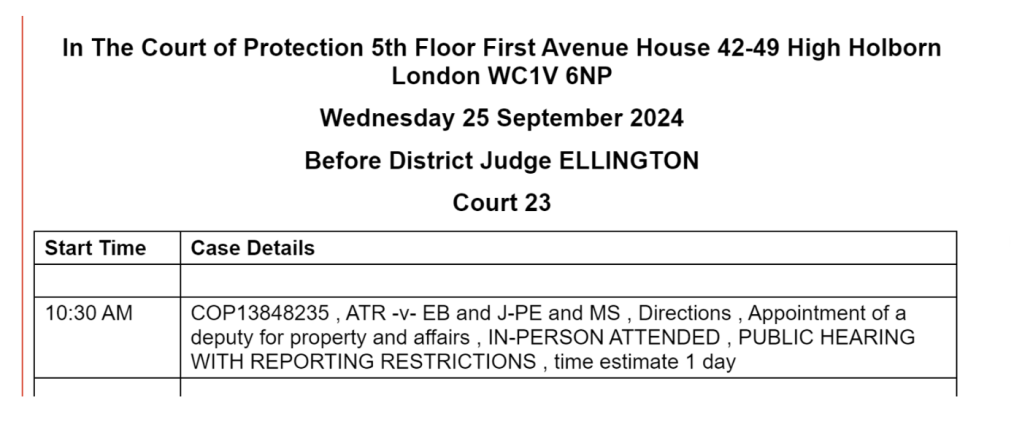

At 10.30am on 25 September 2024 I watched a hearing before DJ Ellington at First Avenue House, listed as below.

Although listed as ‘in-person attended’, as with several other recent hearings, I had no difficulty in obtaining a link to observe remotely. It was a directions hearing concerning the appointment of a deputy for property and affairs and was timetabled to last all day. In fact, I watched only the morning session in which it appeared that there would be no need for further hearings. Certainly a decision was reached on the substantive matter although it might have been that the apportionment of costs remained an issue.

Appearing in the court were two representatives of the three parties concerned (not four as listed – see below). Mr Stewart-Wallace of Ten Old Square appeared for the applicant, EB, and another, whose name I did not properly hear but who could have been a Mr Machin, appeared for the two respondents, J-PE and MS.

I am afraid that I had the same hearing difficulties that I have experienced when observing previous attended hearings. Others say they have had similar difficulties (e.g. The silent courtroom: A remote hearing without sound – and why transparency matters) and I have my own hearing problems. For this reason, I cannot pretend to give a blow-by-blow account of what was said or even be sure who the parties were. I think they were P’s sister and her two children. The listing shows a fourth party but on the Transparency Order ATR is P and EB is the applicant.

The issue before the court seemed relatively simple, although also rather unusual in my limited experience. There had previously been disagreement among the parties as to who should act as Court of Protection deputy for P’s property and financial affairs. As a result, an interim deputy had been appointed by the court and the application now was to make that appointment permanent. One of the parties, the original applicant for the deputyship, agreed with this but the other two were opposed. Their opposition was not to the principle of a professional deputy but to the particular appointment, and this was not because they had anything specifically against the proposed deputy but because they wanted more time to investigate her suitability.

Application for an adjournment

The judge opened the hearing by noting that neither of the respondents was present, having requested that the hearing be adjourned. Their representative said that they were both abroad and, as it appeared later, had not requested a remote hearing until the day before. The applicant’s representative said he saw no reason for them to attend and, in fact, no reason for the hearing because there was no basis for opposing the deputyship appointment. The respondents’ position statement had only arrived the day before, however, and he had not had time to read it properly.

I was surprised by how seriously the judge took the decision as to whether to adjourn the hearing. The respondents were, after all, represented in court by their barrister. She rehearsed in detail previous cases where hearings had gone ahead without one of the parties being present and, afterwards, I found these cases and extracted the parts to which she referred; they are included below.

The judge noted that the case had made no progress for a long time (the TO was dated March 2023) and the respondents had submitted no witness statements, but she also clearly felt she must consider seriously whether their presence was necessary for ‘a fair trial’. The applicant’s representative said he could not see what their presence would contribute. In any case, the use of the term ‘trial’ was itself questionable.

One of the respondents had submitted medical evidence to justify non-attendance and its status also became part of in-depth consideration (the case extracts below cover this issue too). There was a brief adjournment in which the respondents’ barrister attempted to get in touch with them to see if they could join remotely, even at this late stage. That attempt failed.

When the hearing resumed, the applicant’s representative said that, during the adjournment, he had been able to read the respondents’ position statement properly for the first time. He reiterated that there was nothing at all in it that questioned the suitability of the deputy. The respondents had had quite enough time to instruct their representative. He also pointed out that the medical evidence, which referred to one respondent’s health issues and the stress that would be caused by the need to travel, was in another language with only an automated rather than certified translation.

The judge decided that the hearing should proceed. She reiterated the lack of progress to date, the interim deputy having been in post since July 2023. There had been several previous delays with at least one other hearing already having been adjourned. One respondent had provided medical evidence for non-attendance that she did not consider to be sufficient and the other had supplied no evidence.

The judge then referred to Section 1.1 of the Court of Protection Rules 2017 which says: “These Rules have the overriding objective of enabling the court to deal with a case justly and at proportionate cost, having regard to the principles contained in the Act.” It goes on to say:

(3) Dealing with a case justly and at proportionate cost includes, so far as is practicable—

(a) ensuring that it is dealt with expeditiously and fairly;

(b) ensuring that P’s interests and position are properly considered;

(c) dealing with the case in ways which are proportionate to the nature, importance and complexity of the issues;

(d) ensuring that the parties are on an equal footing;

(e) saving expense;

(f) allotting to it an appropriate share of the court’s resources, while taking account of the need to allot resources to other cases;

Further delay would impact dealing with the case expeditiously, imposing a penalty on applicants in other cases. It would also be against P’s interests as her estate was ‘not huge nor complex’ and the costs of continuing action would be taken from her assets .

The respondents’ position was that their concern about P’s finances had caused significant stress and that they had not been convinced by a statement given by the interim, and now proposed permanent, deputy which had been provided to the court previously. They continued to seek reassurance about her performance. However, the judge said that they had provided no evidence to support their concern. She accepted that their representative had not been instructed for this particular hearing but he had been acting for them for over a year. The stress of travel would not have prevented a remote hearing and no timescale had been given for when the respondent with the medical certificate would be fit again. She was therefore refusing to grant an adjournment.

Application for the appointment of a deputy

Returning to the decision about the deputy, the respondents’ representative said that they felt they were ‘still in the dark’ about P’s affairs and would be happier with more information, referring to ‘everything in paragraph 12’, presumably of their position statement. They were not suggesting that the deputy’s hands should be tied but they wanted to be sure P’s affairs had been fully investigated and to have more information about actions already carried out. The judge suggested that she could order the parties to notify the court of their requirements in these respects and that she could then order the deputy to make a report, including progress towards making a statutory will. She was, however, concerned about the costs, which would come from P’s assets.

The applicant’s representative expressed his concerns about this idea, referring to the poor relationships existing between the parties and giving his view that it would be a ‘recipe for disaster’ for them to be communicating with each other and with the deputy outside of the court. He thought it would be particularly unfair to the deputy but the judge seemed not to give much weight to that, saying that she was a professional and presumably used to such situations.

The judge pointed out that, when deputies were appointed, they made a declaration to the court in respect of their responsibilities, which included making an annual report to the Office of the Public Guardian. This should be sufficient reassurance that they were conducting P’s affairs properly. The deputy named was on the Court of Protection panel of deputies which made her prima facie suitable to hold the position and she had previously summarized the actions she had already taken in a witness statement. Changing deputies at this stage would result in still further costs for P. Referring to the relevant sections of the Mental Capacity Act 2005, she pointed out that, if the parties had particular concerns once the deputy was appointed, they could raise them with the Public Guardian,.

The judge also asked if there was anything on file about P’s attitude to her family members that would help ascertain her wishes and feelings, given that there was no Lasting Power of Attorney and no will. Her doctor reported that she no longer knew who her family were but he had expressed the opinion that, if she had had mental capacity, she would have wanted all the parties to be deputies. The judge said that “Having the parties in attendance would have helped to get a better sense”. (I wasn’t sure where this fitted into the discussion since it had already been decided that none of the parties was to act as deputy. Maybe she was thinking ahead to how P’s affairs were to be administered and to the statutory will.

The judge concluded that she would order that the existing interim deputy be made permanent. She also decided that it would be disproportionately costly to P to ask the deputy to report to the parties. She would, however, ask that the deputy provide them with a copy of her annual report to the Public Guardian, unless it became apparent that this was not in P’s best interests. She would also order that the deputy should prepare a statutory will for P.

My thoughts

I was surprised that it seemed to be accepted that the parties, having failed to reach agreement among themselves as to who should be appointed deputy, should have a say in who the court should appoint as professional deputy and, with sufficient evidence, could have brought about a change. I thought the decision to proceed without the parties present was eminently sensible in the circumstances, given that it seemed unlikely that their presence would have contributed anything that was not already known. I can imagine, however, that the hearing would have been quite a lot livelier!

Georgina Baidoun was the lay Court of Protection Deputy for her mother’s Property and Financial Affairs until her mother died in 2021. Because of the difficulties she experienced with several applications to the Court, and with the Office of the Public Guardian in connection with her annual report, she has retained an interest in these areas, including attending Court of Protection Users Group meetings. She is keen to share her experiences in the hope that she can help others who have to engage with these institutions with very little help or guidance. She tweets as @GeorgeMKeynes

Appendix: Case Law cited

Morgan & Anor v Egan

Morgan & Anor v Egan [2020] EWHC 1025 (QB) (01 May 2020)

51. For these reasons, I have concluded as follows:

Grounds 1, 2 and 4 are arguable and the appeal is allowed on those grounds. In summary: HHJ Sullivan erred in law and reached a decision that was not properly open to her in refusing to adjourn without seeking or permitting Mr Morgan to file further medical evidence. In the light of evidence filed subsequently, the error has been shown to be material. The judge should not have proceeded with the trial.

26. The only qualification to this is that, in reviewing the trial judge’s exercise of discretion, the appellate court must be satisfied that the decision to refuse the adjournment was not “unfair” in terms of Article 6 ECHR. This does not, however, mean that in any given situation, only one outcome is fair: Terkuk v Beresovsky [2010] EWCA Civ 1345, [18]-[20] (Sedley LJ), cited with approval in Solanki v Intercity Telecom Ltd [2018] EWCA Civ 101, at [32]-[35] (Gloster LJ).

Grounds 1, 2 and 4: The judge’s treatment of the medical reasons for adjournment

The following relevant principles can be distilled from the authorities:

(a) A litigant whose presence is needed for the fair trial of a case, but who is unable to be present through no fault of his own, will usually have to be granted an adjournment, however inconvenient it may be to the tribunal or court and to the other parties: Teinaz, [21] (Peter Gibson LJ).

(b) However, the court must satisfy itself that the inability of the litigant to be present is genuine, and the onus is on the applicant to prove the need for such an adjournment: ibid.

(c) In considering the need for an adjournment, it is important to focus on the nature of the hearing and the role that the party claiming to be unfit is called on to undertake in it, bearing in mind:

(i) any reasonable accommodations (e.g. breaks, hearing evidence remotely etc.) that can be made to enable effective participation; and

(ii) that if the party is financially able to instruct legal representatives and able to give effective instructions to them, his absence may, depending on the facts, be of little consequence.

See Decker v Hopcraft [2015] EWHC 1170 (QB), [27]-[28] (Warby J).

(d) Generally, the court should adopt a strict approach to scrutinising the evidence adduced in support of an adjournment application on the grounds that a party or witness is unfit on medical grounds: Mohun-Smith v TBO Investments Ltd [2016] 1 WLR 2919, [25] (Lord Dyson MR).

(e) Where medical evidence is relied upon in support of an application for an adjournment, it should:

(i) identify the medical attendant and give details of his or her familiarity with the party’s medical condition (detailing all recent consultations);

(ii) identify with particularity what the condition is and what features of it prevent participation in the trial process;

(iii) provide a reasoned prognosis; and

(iv) give some confidence that what is being expressed is a reasoned opinion after a proper examination.

See Levy v Ellis-Carr [2012] EWHC 63 (Ch), [36] (Norris J), approved in Forresters Ketley v Brent [2012] EWCA Civ 324, [26] (Lewison LJ).

(f) Accordingly, a “sick note” may well be insufficient to justify an adjournment, particularly if it refers only to an unfitness to attend work. However, in considering whether that is so, the court must consider (i) the pressure under which GPs are working and the difficulties that may be faced by a litigant in person in obtaining more a detailed report and (ii) the frequency with which late, unmeritorious adjournment applications are made: Emojevbe v Secretary of State for Transport [2017] EWCA Civ 934, [31] (King LJ); Hayat, [41] (Coulson LJ).

(g) If the court is not satisfied as to the quality of the medical evidence supporting an adjournment application, the court has a discretion (not a duty) to conduct further enquiries – e.g. by seeking a fuller report in short order: Teinaz, [22] (Peter Gibson LJ); Solanki, [35]; Hayat, [42].

(h) If there is a challenge to the exercise of this discretion, it is incumbent on the challenger to show that the further enquiries would have led to a different decision: Hayat, [43].

General Medical Council v Ijaz Hayat

24. The Tribunal considered the application to continue in Dr Hayat’s absence on the basis of these three pieces of medical evidence (paragraphs 22 and 23 above). The relevant part of their determination is at paragraphs 15-19, in these terms:

15. The Tribunal notes that there is a burden on medical practitioners subject to a regulatory regime to engage with the regulator, both in relation to the investigation and ultimate resolution of allegations made against them.

16. It follows that where a medical practitioner seeks an adjournment of a hearing, on the basis that they are not fit enough to attend, then it is their responsibility to ensure sufficient evidence is presented to the Tribunal to establish that this is the case. The Tribunal is satisfied that Dr Hayat is aware of that responsibility, as a result of various communications with him.

17. The Tribunal considered the email sent on Dr Hayat’s behalf this morning at 08.55am and subsequent Statement of Fitness for Work for Social Security of Statutory Sick Pay sent during the course of the afternoon. This document indicates that Dr Hayat is not fit for work because of the following conditions:

This document indicates that Dr Hayat is not fit for work and does not suggest that he is not fit to attend and fully participate in these proceedings. It essentially reiterates the medical information from during the hospital admission.

18. The Tribunal considered that it can conclude on the basis of present information that Dr Hayat has voluntarily absented himself from this hearing. The Tribunal has therefore determined to accede to your application today to proceed in Dr Hayat’s absence.

19. The Tribunal is aware of its duty to ensure that proceedings conducted in the absence of the doctor are fair and to take reasonable steps to expose any weaknesses in the GMC case.”

68.Although there are one or two cases which put the emphasis on unfairness (see for example Terluk v Berezovsky [2010] EWCA Civ 1345), that emphasis is explicable on the facts of the cases themselves (Terluk was about an alleged breach of natural justice), rather than constituting a more general statement of principle. Moreover, I note that in Dhillon v Asiedu [2012] EWCA Civ 1020 at [33], this court explained why the Tanfern and Turluk approaches were “both consistent and analogous”. Baron J, with whose judgment both Arden and Davis LJJ agreed, said:

“Although the language in these two cases is entirely different, the foundation of the decisions is both consistent and analogous. The conclusions which I derive from the authorities are that:

a. the overriding objective requires cases to be dealt with justly. CPR 1.1(2)(d) demands that the Court deals with cases ‘expeditiously and fairly’. Fairness requires the position of both sides to be considered and this is in accordance with Article 6 ECHR.

b. fairness can only be determined by taking all relevant matters into account (and excluding irrelevant matters).

c. it may be, in any one scenario, that a number of fair outcomes are possible. Therefore a balancing exercise has to be conducted in each case. It is only when the decision of the first instance judge is plainly wrong that the Court of Appeal will interfere with that decision.

d. unless the Appeal Court can identify that the judge has taken into account immaterial factors, omitted to take into account material factors, erred in principle or come to a decision that was impermissible (Aldi Stores Limited v WSP Group Plc [2007[ EWCA Civ 1260. [2008] 1 WLR 748, paragraph 16) the decision at First Instance must prevail.”