By Claire Martin, 23rd October 2024

Editorial note: Another observer (Meg Niven Withers, a social worker) also watched this same hearing and has blogged separately here: Moving forward in Re A (Covert Medication: Closed Proceedings): A social work perspective

The case (Re: A) has been in the Court of Protection since 2018 and we’ve been following it since May 2020. It is now at an end.

It concerns a young woman with a mild learning disability and primary ovarian insufficiency who refused to take HRT medication without which she would not achieve puberty. The judge, HHJ Moir, found that this was due to her mother’s influence on her and authorised her removal from her mother, and deprived her of her liberty in a care home where she didn’t want to be. The court restricted and then stopped contact between the young woman and her mother in the hope that (without what they determined was her mother’s discouraging influence) she would agree to take the medication – and when that failed, the judge held “closed” proceedings (excluding the mother, and public observers) and authorised covert medication. When HHJ Moir retired, and another judge, Mr Justice Poole, took the case on, he almost immediately ordered that the closed proceedings should come to an end. After a series of public hearings, he finally ordered that A was to be informed that she had been covertly medicated, that it was now her decision whether or not to continue to take the HRT medication (which – now she’s achieved puberty – is clinically recommended for life on a maintenance dose) and that she would finally be allowed to return home to live with her mother, after 5 years living in a care home. That judgment was appealed by the Local Authority, the NHS Trust and the Official Solicitor but was upheld in the Court of Appeal.

There was then an ‘implementation hearing’ on 24th June 2024 (blogged here) which focused on how these decisions were to be put into practice.

By the time of the hearing I observed, on Monday 14th October 2024, before Mr Justice Poole, sitting at Sheffield Combined Court, the young woman (A) had been back home with her mother for just over three months (since 5th July 2024) and taking her HRT medication voluntarily. The judge said: “A’s return home has been a success”.

I was very pleased to be able to observe this hearing. This is a case that has been of significant interest to me, both as a public observer with the OJCOP project, and as a clinician working in health services, with a keen interest in how we use our power in relation to those we care for.

In this blog I am going to report on the hearing, focusing on the outcome of implementing Poole J’s 2024 judgment, then discuss the transparency issues, and finally end with brief reflections.

The hearing

A and her mother (B) were in court, along with counsel for all parties:

- Joseph O’Brien for the NHS Trust

- Mike O’Brien for A’s mother (B)

- Sam Karim for the protected party, A, via the Official Solicitor

- Sophia Roper for the Local Authority

The hearing started late because A spoke to Poole J in private first. The judge informed the court: “I was delayed as I was meeting [A] and I told her there would be observers”. Poole J did an excellent job of balancing open justice with ensuring that A and her mother were informed of the reasons for our presence and with enabling them to retain some privacy.

Sophia Roper (counsel for the applicant Local Authority) gave an opening summary: Very briefly, [this is a] long-running case concerning [A] … the court will recall that some time ago [A] left her mother’s care and was placed in a residential placement away from her mother. There was a period of no contact with her mother and a period of restricted contact. In your Lordship’s most recent judgment, [you decided] it was in [A’s] best interests to go home. I am not going to go into further detail. I will focus on the positives. My Lord, [A] did go home on the 5th July and she has been there ever since. You’ll have seen from evidence filed that things are going well. She is smiling when I say that. Both the comments of the social workers and the most recent and detailed statement by her mother have demonstrated how successful this is … at the moment … proving to be. There have been …there are still a number of recent teething issues … attending medical appointments. … [A] does not agree to meet the consultant in charge of her hormone treatment and as a result she is being transferred to her GP[1].

It was only on rereading my notes about what counsel said here that I realised she did not refer, at all, to the very important fact that A is voluntarily taking her medication. This was eventually reported to the court by the mother’s counsel, Mike O’Brien.

Counsel for the LA continued: In terms of other things since [A] went home – the social worker has visited [A] at her home, so has the Community Learning Disability Team, fortnightly meetings. Despite [A’s] reluctance to engage with yet more professionals, she has been willing to do so. This has not yet extended to accept care from community agencies … We have had discussions with Mr Mike O’Brien (counsel for A’s mother) as to what might be done … an agency has been engaged but so far [A] has said she doesn’t want support from them. Mr Mike O’Brien thinks that if specific younger carers [could be identified] … she may be interested. The Official Solicitor’s position is that all that can be done is to provide encouragement.

So, it seemed that, despite all predictions from statutory bodies at the previous June 2024 hearing, A has been willing to engage with professionals from the Learning Disability service and social workers. She has not wanted to go out with carers, as per her ‘Community Access Plan’ and the suggestion was that this might be because she would prefer carers closer to her age. I wondered, also, whether the ‘Community Access Plan’ was a plan that A felt she owned, had been part of drawing up and contained things in it that she wanted to do. All those boxes might be ticked, and just not have been referred to in the hearing. Although, Mike O’Brien did then ask “I would want to be sure what that means – whether B would be consulted”. Counsel for the LA replied: “We would circulate and ask for B’s comments, but it is ultimately the LA care plan. It follows the line set out in [social worker’s] witness statement.“

I thought that the language was interesting: ‘it is ultimately the LA care plan’. I would say it is ultimately A’s care plan, though I might be splitting hairs here, and I think Sophia Roper meant that the LA is drawing up the care plan, and although A’s mother can comment, she is not the author of the document.

Counsel for the LA confirmed that a Deprivation of Liberty in the community is, technically, taking place (A cannot leave her home without supervision) and that the LA has oversight, though not control of, this situation. This arrangement was said to be ‘imputable to the state’ (counsel for LA) and therefore, the court would also need to review the authorisation of this Deprivation of Liberty in twelve months’ time: “Broadly the view between advocates is that proceedings need to shift from ongoing welfare decisions to moving to a process which the court needs to adopt under Liberty Protection Safeguards – to review Deprivation of Liberty in the community.” (Counsel for LA)

At this point in the hearing, I still wasn’t sure, even though counsel for the LA had gone through the draft order for the court, whether A had chosen to take the HRT medication voluntarily at home.

The fact that A is now taking her medication voluntarily emerged piecemeal and with stated caveats during the course of the hearing. It was not specifically stated in the opening summary from the LA counsel – and yet this was the key issue that had led to her being removed from her home with her mother in 2019, had led to contact with her mother being stopped (then restricted) and had resulted in her being covertly medicated each day for several years.

There was reference to a recent hospital admission in September 2024 (unrelated to the HRT issue), during which a blood test was taken, and which did not show expected HRT levels. However, the doctor at the hospital has advised that, given that A had been unwell, the blood tests ‘should not be taken as evidence that she had not been taking [HRT]’ (Counsel for the LA). The judge clarified ‘[A] did take it in hospital’.

Counsel for B (A’s mother) clarified the situation at home: “The first thing to say – this is the first hearing since [A] went home – is that the court made the best interests decision requiring to allow her to go home. I appreciate the various issues about blood tests, but she is indeed taking the medication … after 5 years of attempts by [listed others], her mother was able to get her to do so within a day“.

Poole J expressed some caution in relation to that assertion, but Mike O’Brien asserted that “[g]iven that they have [agreed that A will take the medication] ,… [A] should be given praise that she has taken [the HRT].” Poole J concurred: ‘Ye,s she has reached that decision herself’

So, A had decided, herself, to take the HRT at home. This was the opposite outcome from that predicted by the statutory parties when they appealed Poole J’s judgment this year. I don’t know what, exactly, A’s mother’s role was in A’s decision to do that.

The court has always expressed deep scepticism about whether A’s mother would ever encourage her to take the HRT. A May 2020 ‘Case Summary’ helpfully provided to us (by LA Counsel) states unequivocally: “P’s Mother … insists that P’s behaviour is caused by her situation, that she would improve were she to be allowed to return home and that she would engage with treatment then” but continues to say that this statement “must thus be treated with the utmost scepticism”. (§24)

Both things can be true though: i.e. it can be true both that A’s mother failed to encourage her to take the medication AND that once she was removed from her mother she refused to take the medication because of the situation she’d been placed in. I would suggest:

- It might have been true that A’s mother had (as HHJ Moir found in her original judgment) ‘failed to encourage’ her to take the HRT:

- And, A’s mother might also have been correct that, once A was removed from her home (and I would add, her key attachment relationship), her ‘behaviour is caused by her situation’.

It takes little imagination to put yourself in A’s shoes. A has a mild learning disability and a diagnosis of Asperger’s. She lived at home all her life until age 18, with little formal schooling, hardly any other relationships (it was reported) other than those with her mother and grandmother, and some contact with her mother’s friends and their children. She was described by HHJ Moir as having an ‘enmeshed’ relationship with her mother – which is a specific psychological term emphasising “the role of family relationships in an individual’s ability to function. According to Minuchin, enmeshed family members struggle to define themselves outside the family.” [see website here]. And then – in 2019 – she was abruptly removed from her home. Notwithstanding the clear and rational reasons for this – to facilitate medical treatment to protect her long-term health – the court, I would suggest, did not appreciate the strength of an ‘enmeshed’ relationship, nor the damage that can be caused by a sudden removal of that relationship. The Case Summary (from May 2020, after A had been moved to the care home) continues:

19. Issues regarding P’s care continue. In particular:

a. P neglects her personal hygiene, has not showered since 17 March 2020 and continues to use wipes to clean herself;

b. P refuses to change her clothes, and has not done so fully since 23 March 2020;

c. P will refuse to eat and drink for periods of time;

d. P is regularly refusing to take her epilepsy medication with the required frequency, and this has worsened over April and May 2020; and

e. P is also refusing to engage in any social activities and is spending increasing time in her room.

It was submitted at that time “that there is a consensus of opinion amongst those involved in P’s care that P is still being largely influenced by P’s Mother, and negatively so, to this end”. It wasn’t considered, however, that an abrupt removal of your main relationship might be the cause of the deterioration in mental wellbeing. Whatever the situation between A and her mother in relation to the HRT, and although there is no surefire way to know this for a fact, by all accounts A continues to take this medication by choice. It is perhaps worth mentioning that (at previous hearings) it was said that once A had gone through puberty she was at far less risk of health complications than if she had not taken the HRT to enable her to go through puberty. The HRT medication she now takes was described as ‘maintenance’ medication, which, whilst important, was not as vital for her health and wellbeing.

It was interesting to hear the expectations in relation to A’s mother. Sam Karim (counsel for the OS), referring to A’s clinical appointments said: “I thought it was undisputed, that [A’s] mother would take all reasonable steps for her daughter to attend appointments.” Poole J clarified, in his ex-tempore (oral) judgment, the extent of expectations for A’s mother in relation to her medical care: “She will use her best endeavours to attend medical appointments”

This is all set against the backdrop of the entire system around her believing that she will do the exact opposite. That view, of course, was informed by their engagement with A’s mother in 2018 following the awareness (during a hospital visit when she was acutely unwell with seizures) that A had not gone through puberty. It would be very interesting to go back to understand the nature of that engagement and the safeguarding alerts that were raised. I wonder whether, for her own reasons, A’s mother might have been frightened and defensive at that time, and felt intruded upon, and she herself might have needed a lot of help, as well as A. This might have been offered to her, of course, and the Local Authority and NHS Trust might well argue that, had they not brought proceedings to court, then A’s mother might never have reached the position she is in now, encouraging her daughter to take the prescribed medication and allowing carers to take her out and about. It will never be known where alternative paths might have led.

Here are some key points from Mr Justice Poole’s oral judgment at this hearing. In his nutshell summary of the history of the case, he said:

“The case first came before me some time ago: even then it was a complex issue in the COP. At that time [there were] difficult circumstances: [A] [was in a] residential home, an order was made that resulted in her [not seeing her mother] … [she was in] receipt of medications, which she knows about now, and the circumstances. An application by her mother for a decision on best interests for residence was made in the absence of knowledge of the medications. It also had an effect on the observers, [they were] not aware of the closed hearings. In any event, a series of decisions was made by the court … [and] ultimately earlier this year, the difficult decision was upheld on appeal, to make a best interests decision for [A] to leave the residential home and return home to the care of her mother, and to inform her of what had happened in terms of the medications.”

In relation to what has happened following the implementation hearing in June 2024, Poole J said:

“[A] returned home on the 5th July this year, Her mother has told the court in evidence that [A] takes the HRT daily by choice and she supports her to do so. […] She also told me that it shouldn’t have been administered to her [secretly]. Unfortunately, [A] had to go into hospital for an acute medical issue in September for 8 days: she took the HRT. Her mother was supportive of this. This is very welcome news to the court, given the involved history of the case, [which is] set in a number of published judgments. [A] is engaging with her GP. [A] says she enjoys going out in the local area, city centre… [lost] she doesn’t want that to have to change. I have read discussions with [A] with the solicitor instructed by the OS, sparing [A’s] blushes … [she uses] abusive language … but she certainly made her views clear … I do urge her to engage with those who do seek to help her – medical professionals, social workers. There has been some engagement with health care professionals, inpatient care for example.”

In relation to the judgment which ordered that A must return home, be informed about the covert medication and be allowed to make her own decision about whether to continue to take the HRT, Poole J said:

“The OS records that [A’s] return home has been a success, largely .. It’s right to say matters might have taken a different turn if the court … [inaudible]. So far it has been to her benefit and is a success. I recognise risks, but the fact is that they haven’t [happened ]…. Firstly, though I accept [A] and her mother will not see Dr X, the Trust has tried their best to support [A] and her mother, they have the court’s thanks. Likewise, the Local Authority have, over a number of years, tried to support [A] and her mother. They might not see it that way, but they have tried to offer support. [inaudible] … Also, and very important, [A] and her mother … [A] has taken the right decision to take this medication, and the court had to place trust in you [speaking directly to A’s mother].”

And in relation to next steps Poole J declared:

“Parties have taken the position that the court should now make an order which brings to an end repeated proceedings in relation to residence, care, and contact with others, but which would allow for a review as follows: [care] arrangements and there will be a support and assistance community plan. Under that plan there will be a Deprivation of Liberty. There will be restrictions on her that amount to Deprivation of Liberty. I authorise [them] as necessary and proportionate in A’s best interests, but as case law dictates, there should be a review within 12 months, and a date will be set for a review hearing.”

Mr Justice Poole concluded proceedings by addressing A:

“Thank you all very much indeed … the substantive proceedings [now] come to an end. [A] I wish you the best – if things go well there will be a review in a year’s time. It might be on the papers, but that depends on what happens in the next year. [A] you remain at home with your mum and it’s very nice to meet you”.

I heard A say ‘thanks’ and we saw A and her mum make a very speedy exit out of the courtroom together. I think I would have done the same.

Access Issues

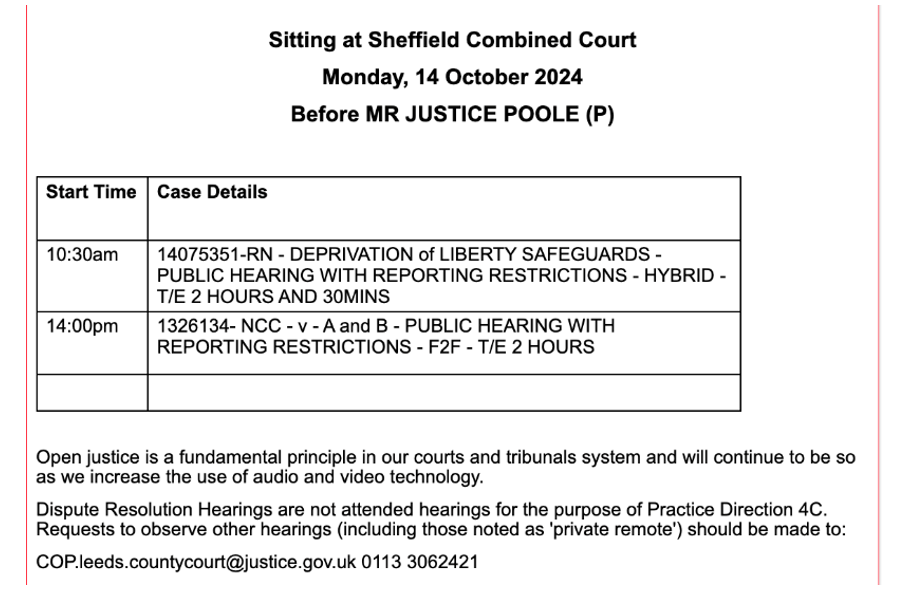

This is the listing for the hearing below. It was listed under the Sheffield Court of Protection Courtserve listing service, which is helpful as it means that the public can see when a High Court judge is on ‘circuit’ and means that observers in that area who might want to observe a High Court judge in person are alerted to the case. It should also be listed in the Royal Courts of Justice Daily Cause List, and unfortunately it wasn’t. The COP case number is also wrong (it is missing a digit and should be 13236134). I had been expecting the hearing to be held a little later (as had been suggested at the last hearing) and I came across it by chance and noticed ‘NCC v A and B’. Luckily, I was able to observe.

The judge noted that observers had been provided with the Transparency Order (which prevents us naming the public bodies in this case). Poole J turned his attention to what we could actually observe: ”The camera is at the moment just showing a shield … [court staff moving camera around – judge making sure observers could have a good view of the court – but we couldn’t see him and the court] now they can see me in side view … if it could swing to the right a little bit, I don’t know [A] and [B – mother], move along two seats along [he explained to give them more privacy from observers so they were out of camera-shot, and also explained why there were observers in court].It was heartening to see a judge take time to ensure, firstly, that the protected party (A) and her mother (B) could be afforded some privacy within what was a public hearing, and that open justice was achieved.

It’s not the judge’s fault that, in this particular court, there was only one camera, meaning that we could either see counsel as they addressed the judge, or the judge when he spoke to counsel. It is often hard to hear what is said in court when the hearing is hybrid (i.e. some people are in a physical courtroom and others on a remote link), and not being able to see each person speak makes it even harder. Other courts (for example, some regional courts and some courtrooms in the Royal Courts of Justice) have multiple cameras to enable all people who will be speaking to be seen at the same time. This seems to me to be the minimum technology required for effective transparency.

Microphones are another issue. In this hearing (as with many others) it was often hard to hear counsel if they moved away from their microphone (they stand up to address the judge), and I don’t think the judge was always right in front of his microphone (though of course we couldn’t see him, because the camera was on the main courtroom, not the bench!): his voice was, at times, very quiet. Clip-on microphones would make much more sense to enable a hearing to be properly ‘public’, because of course just being in a room, or on a remote link, does not enable true access to a hearing if the sound quality (and/or camera access) is poor.

Final thoughts

At the end of the last blog about this case, I commented on how sad I felt about what has happened, and A and B’s experiences. At the end of this hearing I felt very differently.

A had spoken to the judge. She had made her views about the carers and health care professionals very clear to him. He spoke to her kindly and compassionately. She was able to hear what people in court had to say about her and her mother, and, importantly, she strode out of court on her own before anyone else (other than the judge) had left.

There is something about being able to have agency and choice that is very important to us all, even if we are deemed to lack ‘capacity’ for certain decisions.

Now that the substantive issues have been decided and the case is effectively over, we will be publishing a reflections blog about Re A, the issues it raises and the views and feelings which have been stirred in relation to what has been a key case for the Court of Protection.

Claire Martin is a Consultant Clinical Psychologist, Cumbria, Northumberland, Tyne and Wear NHS Foundation Trust, Older People’s Clinical Psychology Department, Gateshead. She is a member of the core team of the Open Justice Court of Protection Project and has published dozens of blog posts for the Project about hearings she’s observed (e.g. here and here). She is on X as @DocCMartin and on BlueSky as @doccmartin.bsky.social

Appendix

Previous blog posts about and published judgments from this case

In reverse chronological order – start with the blog at the bottom to read ‘from the beginning’

- Tangled webs, ‘enmeshment’, and breakdown of trust: Re A: (Covert medication: Closed Proceedings) – an implementation hearing

- Still no exit plan and “we are some way away from the ideal scenario”: Re A (Covert medication: Closed Proceedings) [2022] EWCOP 44

- Unplanned disclosure and (still) no agreed ‘exit plan’: Re A (Covert medication: Closed Proceedings) [2022] EWCOP 44 continues

- New Guidance on Closed Hearings from the Vice President of the Court of Protection

- No ‘exit plan’: Re A (Covert medication: Closed Proceedings) [2022] EWCOP 44

- Covert medication of persons lacking capacity: What guidance is there?

- Reflections on open justice and transparency in the light of Re A (Covert Medication: Closed Proceedings) [2022] EWCOP 44

- “I have to tell you something which may well come as a shock”, says Court of Protection judge

- Statement from the Open Justice Court of Protection Project concerning an inaccurate and misleading blog post

- Medical treatment, undue influence and delayed puberty: a baffling case

The published judgments are:

- The Local Authority v A and B [2019] EWCOP 68 HHJ Moir, 18 June 2019

- A Local Authority v A and B [2020] EWCOP 76 HHJ Moir, 25 September 2020

- Re A (Covert Medication: Closed Proceedings) [2022] EWCOP 44 Poole J, 7 October 2022

- Re A (Covert Medication: Residence) [2024] EWCOP 19 Poole J, 20 March 2022

- Re A (Covert Medication: Residence) [2024] EWCA Civ 572 – this is the Court of Appeal judgment and the hearing itself can be watched on YouTube here: Re: A (By Her Litigation Friend, The Official Solicitor)

[1] It later transpired that A’s GP has not agreed to oversee her HRT medication, and I wasn’t clear, at the end of the hearing what the plan for that was. The judge explained: “it’s clearly in [A’s] best interests to have oversight of her HRT and if that requires involvement of her GP … then I hope that will happen. I have discussed with [A] the need for medical involvement … and sometimes we don’t like seeing doctors but it’s necessary to do so sometimes.”

2 thoughts on “A is back home and taking her medication voluntarily: The final hearing in Re A (Covert Medication: Closed Proceedings)”