By Celia Kitzinger, 18th December 2024

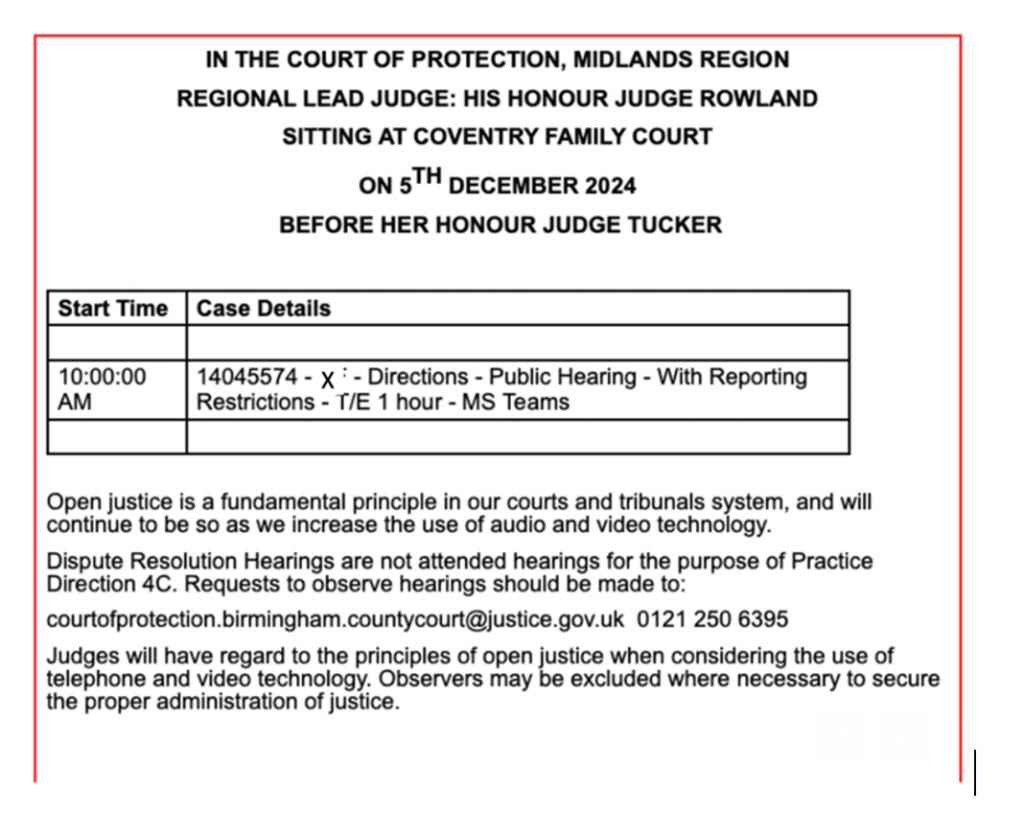

The hearing I observed on 5th December 2024 (COP 14045574) before HHJ Tucker sitting in Coventry was an application to send someone to prison. The hearing lasted for about 35 minutes and I was able to observe about 20 minutes of it, missing the beginning due to not having been sent the link until half an hour after the listed start time.

There are new allegations that LB (the initials used in the previously published judgments) has breached a court injunction – an injunction she’s breached many times before. At an earlier hearing she received a suspended sentence of five months in prison, on condition of no further breaches. If she is found to have breached the injunction again, it is expected that she will now serve that prison sentence.

Recently, however, an expert has provided a report saying that LB doesn’t have the requisite mental capacity – which would mean (said the judge) that the injunction should not have been made and no further steps can taken in relation to committal. The other parties (the Local Authority and the Official Solicitor [acting for the protected person]) do not accept that expert opinion and there’s a full-day hearing on 19th December 2024, where the expert will present her evidence and be cross-examined.

Background

The protected party, X, is “an intelligent young adult” who has suffered very serious physical, emotional and sexual abuse from LB. X wants to maintain a relationship with LB but not to be subject to bad behaviour from LB which, according to the published judgments, includes demanding money, asking X to have sex with men to pay LB’s debts, including drug debts, and selling (or threatening to sell) intimate images of X (Lincolnshire CC v X & Ors [2023] EWCOP 52).

Injunctions made by Mrs Justice Lieven were served on LB (and another respondent) on 5th May 2023. The injunctions said that neither of them should have contact with X – not by telephone, by post, or via social media.

On that very date, immediately after receiving the injunctions forbidding contact, LB phoned X, saying it was “all lies”. She phoned again multiple times that month, as did the other respondent, asking X to stop the injunctions (obviously not within X’s power), and asking for money from X, and variously claiming that LB was in a coma in hospital and “dying and it is all your fault”, and that LB was prostituting herself. The judge found this behaviour to be “manipulative”, “cruel and calculating”. In a subsequent hearing, she found “very little evidence… of any genuine remorse on the part of the respondents”. Given that X also values and wants to maintain a relationship with LB, LB’s behaviour caused X “intense distress, upset and confusion”. The judge sentenced both LB and the other respondent to a period of 5 months in prison. Since there had been some months’ gap between the last breaches and the sentencing hearing, the judge suspended the custodial sentence on condition there were no further breaches (Lincolnshire CC v X & Ors [2023] EWCOP 53).

To protect X, who is anxious, frightened and “dysregulated”, due in part to her diagnoses and mental health conditions, and also as a consequence of these proceedings, the committal proceedings were – very unusually and after careful consideration – held in private. The two published judgments concern first, the decision, made in the context of the judicial commitment to open justice, to hold the proceedings in private (EWCOP 52); and second, the committal decision (EWCOP 53).

The hearing of 5th December 2024

When I saw the listing for this case, I assumed that it was nothing to do with the committal, but rather that it concerned decisions for X’s ongoing welfare. That’s because it wasn’t listed in accordance with the Practice Direction for Committal for Contempt of Court hearings: it didn’t say it was a committal hearing and didn’t name either an applicant or an alleged contemnor (which listings for committals are supposed to do) so I had no reason to think that’s what it was. But it turned out to be exactly that.

It took some persistence to gain admission to the hearing. I asked for the link the evening before (19.22 on 4thDecember 2024), resent the request at 09.19 the following morning, and finally received the link at 10.30am for the hearing, which of course had already started. I gather it started around 15 minutes before I joined.

The applicant was LB and as I joined her lawyer, Will Harrington (of Harrington Solicitors), was saying that “the defendant has a report saying she’s not got capacity, so this is a live issue”.

I gathered that there had been a previous hearing a month earlier (4th November 2024[i]) at which LB’s solicitor had raised concerns as to whether LB: (a) has capacity to conduct these proceedings; (b)) understands the terms of the injunction made by Lieven J; and (c) understands the condition attached to the suspended sentence previously imposed by the court. Proceedings had been adjourned to allow for her capacity to be assessed by a consultant psychiatrist, whose report was now before the court. I think it is being said that she has, or may have, a learning disability as the “cause” of her lack of capacity.

Concerns have been expressed about the quality of the report. The psychiatrist “appears to be raising the bar of capacity to conduct these proceedings, and understand the terms of the injunction too high” said counsel acting for X via the Official Solicitor (Benjamin Harrison, Serjeants’ Inn Chambers).

The judge decided that the hearing on 19th December will be used to determine LB’s capacity. Either she will have the requisite capacity, in which case her lawyer can take her instructions and the committal hearing will proceed (with reasonable adjustments if necessary, e.g. “it might need to go slower”). Or she won’t have capacity, in which case the judge hoped to get the Official Solicitor on board to represent her (obviously with a different lawyer from the one representing X via the OS). “The point I’m making,” said the judge, “is this. Can I ask the OS to be effectively on standby so they can become involved in these proceedings at short notice?”

Counsel for X said he thought that was “a proportionate and appropriate way forward”.

Counsel for LB said he had “a preference for the OS to be instructed today, but can understand the view that is putting the cart before the horse”.

The judge pointed out that she could “invite the OS to act for the defendant in the light of the report, but it’s a live issue with regard to capacity, which will be determined on the 19th. It’s up to the OS what she wants to do. If she says ‘no’, and declines the invitation, well, fine. If she says ‘yes’, there we are – and she may have to step away at a later point if LB has capacity. Does anyone oppose that process?”. Nobody did.

There was then a brief discussion about the advisability (or not) of inviting an addendum report from the consultant psychiatrist prior to the next hearing – as submitted by LB’s counsel, who was “uncomfortable that [the psychiatrist] whose duty is to the court is going to be ambushed by questions she has no notice of. She should have notice of questions from the litigation friend so she knows what the issues are. The evidence will be better for having had time to think about the issues raised by other parties”. Counsel for the Local Authority (Jack Anderson of 39 Essex Chambers) expressed concern about “cross-examination by email” and counsel for X referred to “full-throated remarks in my Position Statement saying the expert has got things wrong”. I think the outcome was that there was no invitation to provide an addendum report, but that the judge ruled Position Statements should be provided to the expert in advance of the hearing (and I think she said the rest of the bundle too).

Reflections

I’ve watched several committal hearings this year at which a question mark has arisen as to whether the person found to be in contempt of court (and facing a prison sentence as a consequence) has the requisite mental capacity – by which is meant, separately, (a) their capacity to conduct the proceedings; and (b) their capacity to understand and make decisions about the injunction itself. I’ll start by outlining what I understand to be the law in this area – bearing in mind I’m not a lawyer and happy to be corrected by those who are.

An injunction can be made against a protected party (i.e. a party, or an intended party, who lacks capacity, within the meaning of the Mental Capacity Act 2005, to conduct the proceedings), but only if he or she understands the nature and requirements of the injunction (Wookey v Wookey [1991] 3 All ER 365). This is because the test of capacity to conduct proceedings and the test of capacity to comply with an injunction are two different tests (see P v P (Contempt of court: Mental capacity) [1999] unreported).

Capacity to conduct proceedings is set out in case law predating the Mental Capacity Act 2005: Masterman-Lister v Brutton & Co. [2002] EWCA Civ 1889 – but in terms clearly congruent with the Act, being based on early reports on which the Act was based.

“§79. The Judge found assistance in recommendations made by the Law Commission in 1995, in Part III of its report Mental Incapacity (Law Com No 232). The report drew attention… to the need that a person should be able both (i) to understand and retain the information relevant to the decision which has to be made (including information about the reasonably foreseeable consequences of deciding one way or another or of failing to make any decision) and (ii) to use that information in the decision making process. I that that he was right to have regard to those recommendations. I think he was right, also, to have in mind the qualifications … that a person should not be held unable to understand the information relevant to decision if he can understand an explanation of that information in broad terms and simple language; and that he should not be regarded as unable to make a rational decision merely because the decision which he does, in fact, make is a decision which would not be made by a person of ordinary prudence.“

Capacity to conduct proceedings is fleshed out in more detail (albeit in relation to matters that sound very different to those with which the Court of Protection is concerned) in Bailey v Warren [2006] EWCA Civ 51:

“…The assessment of capacity to conduct proceedings depends to some extent on the nature of the proceedings in contemplation. I can only indicate some of the matters to be considered in accessing a client’s capacity. The client would need to understand how the proceedings were to be funded. He would need to know about the chances of not succeeding and about the risk of an adverse order as to costs. He would need to have capacity to make the sort of decisions that arise in litigation. Capacity to conduct such proceedings would include the capacity to give proper instructions for and to approve the particulars of claim, and to approve a compromise. For a client to have capacity to approve a compromise, he would need insight into the compromise, an ability to instruct his solicitors to advise him on it, and an understanding of their advice and an ability to weigh their advice…” §126

The ability to manage the dynamic nature of proceedings is emphasised by Macdonald J in TB v KB and LH (Capacity to Conduct Proceedings) [2019] EWCOP 14: he said that legal proceedings are “not being simply a question of providing instruction to a lawyer and then sitting back and observing the litigation, but rather a dynamic transactional process, both prior to and in court, with information to be recalled, instructions to be given, advice to be received and decisions to be taken, potentially on a number of occasions over the span of the proceedings as they develop.” (§29)

Capacity to understand and comply with injunctions means being able to understand the orders made, and having the capacity to obey them (Wookey v Wookey [1991] 3 WLR 135 ). In P v P, the Court of Appeal held that a limited degree of understanding could be sufficient to found liability for contempt. There was no need for a full understanding of the finer points of law provided the contemnor understood what he must not do and what the consequences of a breach might be. It’s also been observed that a person might well understand the terms of an order when explained but then, by reason of their mental impairment, be unable to make the decisions necessary to comply with that order thereafter (Cooke v DPP [2008] EWHC 2703 (Admin)). Where there’s evidence, retrospectively, that – due to an impairment in the functioning of their mind or brain – the person did not understand the injunction at the time it was made, or was unable to make decisions to comply, then the injunction should not have been made in the first place and proceedings against them must end.

Committal hearings are not particularly common in the Court of Protection, and committal hearings at which the suggestion is made that the presumption of the contemnor’s capacity is displaced are even less common. I’ve observed two others recently – in both cases (as in the one I’ve reported on above) after prison sentences were handed down.

1. James Grundy

There’s a published judgment from August 2023 (Committal for Contempt of Court: Derbyshire County Council -v- Grundy) which sentences Mr Grundy to 28 days in prison for having visited P, unsupervised, at her home on two separate occasions in breach of the injunction forbidding this.

The sentence was suspended – but just a few months later, on 15th January 2024, the case was back in court.

Mr Grundy’s solicitors, who previously accepted that Mr Grundy had capacity to instruct them, now said his capacity was in doubt, and his social worker had produced a report saying that he did not have capacity to conduct the proceedings.

The judge asked whether the Official Solicitor would be willing to act for James Grundy at the next hearing, which is what happened six weeks later. The OS took the position that that expert evidence was required as to Mr Grundy’s capacity and that such evidence ought to be obtained prior to any substantive orders being made on this application. The judge ordered an expert assessment. (I blogged about the case here: Committal and sentencing with a possibly incapacitous contemnor.)

A subsequent committal hearing listed for 15th October 2024 was vacated, and I was then unaware of subsequent hearings (though the judge reports that they were correctly listed) until the judgments were published reporting the outcome. James Grundy was found to have capacity to understand the injunctions against him; breaches of those injunctions were proved (the judge watched “irrefutable evidence” in the form of footage from police body-worn cameras showing Mr Grundy visiting P’s house in breach of the injunction), and Mr Grundy was sentenced to 28 days immediate imprisonment (see Derbyshire County Council v. James Grundy (by the OS) and P (by SB, her litigation friend). Derbyshire County Council v Grundy [2025] EWCOP 1 (T1) (20 January 2025); Derbyshire County Council v Grundy [2025] EWCOP 2 (T1) (29 January 2025)).

2. Lioubov (Luba) McPherson

Luba McPherson received a prison sentence of four months – handed down by Poole J in the Court of Protection because she repeatedly breached court orders forbidding her from posting articles, videos and audio-recordings of her daughter on social media. She has done so, she says, “ to show the distress that my daughter suffers daily, because so-called professionals keep my daughter in deliberately induced illnesses to suit the agenda that she lacks mental capacity“. She refers to her daughter’s treatment as “torture” (all quoted in the judgment, Sunderland City Council v Lioubov Macpherson [2023] EWCOP 3)[ii]

On 3rd December Ms McPherson had intended to appeal against this prison sentence in the Court of Appeal but found instead that her capacity to conduct the proceedings was in question – something she vigorously contests.

The published judgment from the Court of Appeal reports that Ms McPherson’s solicitor, and other members of her legal team, became concerned about her capacity to conduct proceedings during the course of a conference with her in preparation for the Court of Appeal hearing and “she was invited to participate in a capacity assessment which was arranged for 18 November 2024 with Dr Pramod Prabhakaran a psychiatrist experienced in conducting capacity assessments for the Court of Protection”. She declined “in strong terms” ([2024] EWCA Civ 1579). The court gave permission for Dr Prabhakaran to conduct a paper-based assessment of Ms McPherson’s capacity (i.e. without meeting her, based on emails and other documents Ms McPherson had sent to her legal team). On the basis of those documents, the psychiatrist found on the balance of probabilities “the possibility of a delusional disorder” and that “due to her firmly held beliefs which persist despite evidence against these, on balance, her ability to use and weigh up information relevant to the court proceedings is likely to be affected as a result”. The Court of Appeal, having “reason to believe” that Ms McPherson may lack capacity, has referred the case back to a High Court judge for determination and continued the stay of the sentence of imprisonment pending a decision on her capacity, after which the case will return to the Court of Appeal. We will be blogging updates about this case (and will link to them here in due course).

I don’t know how contemnors in general feel about the view that they may lack relevant capacity in relation to committal proceedings (they may simply be relieved that it means no prison sentence) but Luba McPherson made it very clear to the Court of Appeal that she is outraged by any such suggestion. The person’s own views about their litigation capacity are included in the “Certificate: Capacity to Conduct Proceedings” intended for use by capacity assessors as a standard form of report on the matter.

In conclusion: Together, these three cases raise serious concerns about the Court of Protection approach to the people (almost always family members) against whom judges make injunctions and issue committal proceedings. The intention of these injunctions to to protect (what the court determines to be) P’s best interests – and to deter actions contrary to those. When there are different views about P’s best interests between court and contemnor, or when the contemnor is simply unable to understand or comply, or refuses to do so, the situation rapidly becomes deeply problematic. It’s rarely the case that P actually wants to see their family members or close friends sent to prison. It seems to me that (on the whole) judges and lawyers (especially of course the Official Solicitor acting for the protected person whose best interests were the focus of the case from the start) are very much alive to these concerns, but nobody seems to know how best to address them.

Celia Kitzinger is co-director of the Open Justice Court of Protection Project. She has observed more than 580 hearings since May 2020 and written more than 100 blog posts. She is on LinkedIn (here), and also on X (@KitzingerCelia) and Bluesky @kitzingercelia.bsky.social)

[i] I don’t know for sure, and I can’t now check because we can’t search for past hearings in Courtel/CourtServe, but I strongly suspect that the 4thNovember 2024 hearing, like the one I’m reporting on here, was also incorrectly listed and did not comply with the Practice Direction. We are always on the look-out for interesting hearings and we scan the lists every day. It’s unlikely we’d have missed a hearing that said it was a committal hearing.

(ii) We’ve been following this case for a while, and have previously blogged about the committal hearings (see: “A committal hearing to send P’s mother to prison”; and “Warrant for arrest of P’s mother “; see also “An ‘impasse’ on face-to-face contact between mother and daughter” for some background to the case). Luba McPherson had already made an unsuccessful appeal against the custodial sentence as a litigant in person: the judgment dismissing her appeal is here: Lioubov Macpherson v Sunderland City Council [2023] EWCA Civ 574.

One thought on “Capacity and Contempt of Court: The case of LB”