By Jenny Kitzinger, 10th February 2024

Mr G is a man in his sixties with vascular dementia and frontal lobe damage. The Court of Protection has found that he lacks capacity to litigate and to make decisions regarding his residence and care. He has lived mostly in residential care since 2019 – but he doesn’t want this, and believes he is perfectly capable of returning to live in his own flat. The question before the court now is: should his flat be sold?

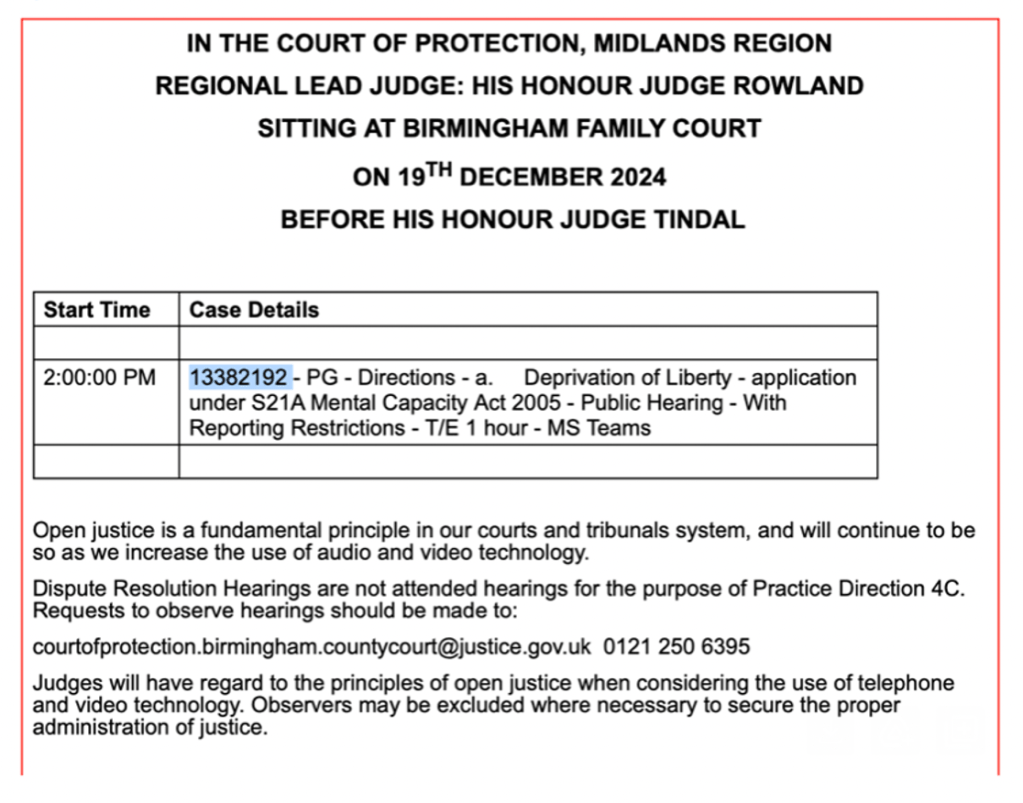

Over the last four years, I have observed multiple court hearings about Mr G (and blogged about them eight times), so when I saw his case number appear in the listings again (COP 13382192) as a Section 21A application (again), I was eager to find out what was happening. The case was listed before HHJ Tindal, who’d also been the judge in all the previous hearings I’d observed.

The application by the Local Authority was to renew the DoLS – and, it turned out, also to get a declaration from the court that it was now in Mr G’s best interests to have his flat sold to pay for his care fees (or, more precisely, to pay his debt to the Local Authority for care fees they had paid so far).

The Local Authority was represented by Olivia Kirkbride. Mr G was represented (via the Official Solicitor as his litigation friend) by Kerry Smith. Also present was Mr G’s court appointed deputy for property and affairs.

Mr G himself did not attend.

This is the latest chapter in a very long-running saga.

In 2020 I wrote about Mr G’s strong and powerfully expressed views in two hearings in Autumn 2020 where he argued against being ‘incarcerated’ against his will (‘Influencing ‘best interests’ decisions: An eloquent incapacitious P’).

I also addressed the fact that the Official Solicitor as Mr G’s ‘Litigation Friend’ opposed his return home in these hearings on the ground it was not in his best interests (‘Should P’s ‘Litigation Friend’ instruct P’s lawyer to promote P’s wishes and leave ‘Best Interests’ to the judge?’)

Another hearing followed in December 2020 at which the judge had hoped to make a decision about Mr G’s residence – but this wasn’t possible due to delays in putting together viable options to choose between; something which the judge criticised as evidence of a lack of co-operation between statutory agencies. See my blog: ‘Unseemly turf wars and uncoordinated care’.

Mr G remained in the care home until the end of September 2021 when it was ruled that he should be allowed to return home with a support plan in place, but within a fortnight, I was watching another court case – an emergency hearing – because serious concerns had been raised by the professionals involved.

A series of four more court hearings followed during the remainder of 2021 as efforts were made to support a trial of Mr G living at home with the support of his partner/ex-partner, Miss F ( “A trial of living at home – a “suspended sentence” of returning to care”).

Previously Miss F had been seen as more of a threat than a help, but a fact-finding hearing to address allegations that Miss F was abusive found this to be untrue (‘Abuse and coercive control? A fact-finding hearing and exoneration’), and in October 2021 Miss F was enrolled to support Mr G living in the community (‘A judicial U-turn? From ‘no contact’ to ‘main carer’.)

By 20th December 2021, however, Mr G was returned to residential care (‘Untenable and unsafe: A trial of living in the community breaks down’).

Mr G has remained in residential care ever since, presumably with another Section 21A application each December – as I assume he continues to object.

This hearing about Mr G’s Deprivation of Liberty (19th December 2024) was straightforward in one way. The judge said there was no evidence to change his view that it was not safe to return Mr G to the community. He also commented that, if anything, Mr G seemed to have disengaged from the process compared to his own previously very active record of participation. This was perhaps, the judge speculated, because Mr G had lost interest in proceedings or simply because he had no more to say. The DoLS was approved with no evidence presented orally against this (except for clear statements from the Official Solicitor that Mr G opposed it, though she did not.)

The application in relation to selling the flat, however, led to some more interesting points. The judge felt it was hard to make a ‘best interests’ decision to “do something Mr G doesn’t want to happen [i.e. sell his flat] to repay the Local Authority for “care home fees for somewhere he doesn’t want to be”. There was, he said, a lack of information to inform such a best interests decision given a lack of clarity about the flat’s value, at what point in time Mr G could have been said to have access to it, and quite what might be owed to the Local Authority. The judge pointed out that if, for example, the flat sold for £50,000 and the debt was £250,000 then selling the flat would ‘not make a blind bit of difference’ [to Mr G] – “The only best interests served by selling the flat would be the Local Authority’s”. But, in Mr G’s mind “selling the flat would cut off Mr G’s hopes of ever going home”.

Trying to find a pragmatic way forward, the judge suggested that one option was that the Local Authority sue Mr G for recovery of the debt – in a court that would simply look at the civil merits of the case, rather than making decisions predicated on Mr G’s best interests.

In the context of the Court of Protection, the best HHJ Tindal felt he could do in the circumstances was to authorise Mr G’s finance deputy to make the decision about whether or not to sell the flat at the appropriate point in time in the future. She could do this on the basis of Mr G’s best interests and investigating the value of the flat and the value of the debt. He added that he didn’t want to put the finance deputy on the spot but did ask if she wanted to say anything – like (he suggested), “For heaven’s sake, what are you doing man?!”. The finance deputy indicated that she didn’t want to say that, instead expressing her understanding, and acceptance, of this plan.

Just as the hearing was concluding, a message was received from Miss F (who had supported the unsuccessful trial of Mr G living in the community back in 2021). She was trying to join the hearing and having difficulties with the link. With apologies to her, the judge decided it was neither practical nor appropriate to try to link her by phone. The hearing was over, and, he underlined that he had not made an irreversible decision – simply, in relation to the flat, authorising the deputy to make this decision some time in the future if she deemed that appropriate.

Jenny Kitzinger is co-director of the Coma & Disorders of Consciousness Research Centre and Emeritus Professor at Cardiff University. She has developed an online training course on law and ethics around PDoC and is on X and BlueSky as @JennyKitzinger

Hi, thanks for posting this. As an ex Safeguarding manager and a Dols/MCA assessor for local authorities, it does highlight several issues which have bothered me for some time in such cases. It is clear what P wants and he does not agree with the decisions made.If he does lack capacity (I say this as I haven’t seen the capacity assessment) then a best interest decision should be made. So far, no problem. However, to charge him for something he doesn’t want or beileive to be a good decision and based on an assessment (that he lacks capacity), is a different step. Had he been detained under S3 MHA, he would not have to pay for a care home, even if the stay was decided by a Best Interest decision , I believe. (There may be case law that I am unaware of). In any event, to try to sell his home against his wishes is not anything to do with his care needs. It seems to me that the need to sell his home is for the interests of the Local Authority. I seem to remember a Judge talking about the meaning of home in a different case. The LA can put a charge on his home and recoup the fees after his death, as they no doubt do in other cases. It sounds like P is not happy in the home and I wonder if a review of the placement and care plan has been undertaken.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Exactly that – why would it benefit him to sell now instead of putting a charge on it for after he dies? Did the court consider that?

LikeLike