By Claire Martin, 28th April 2025

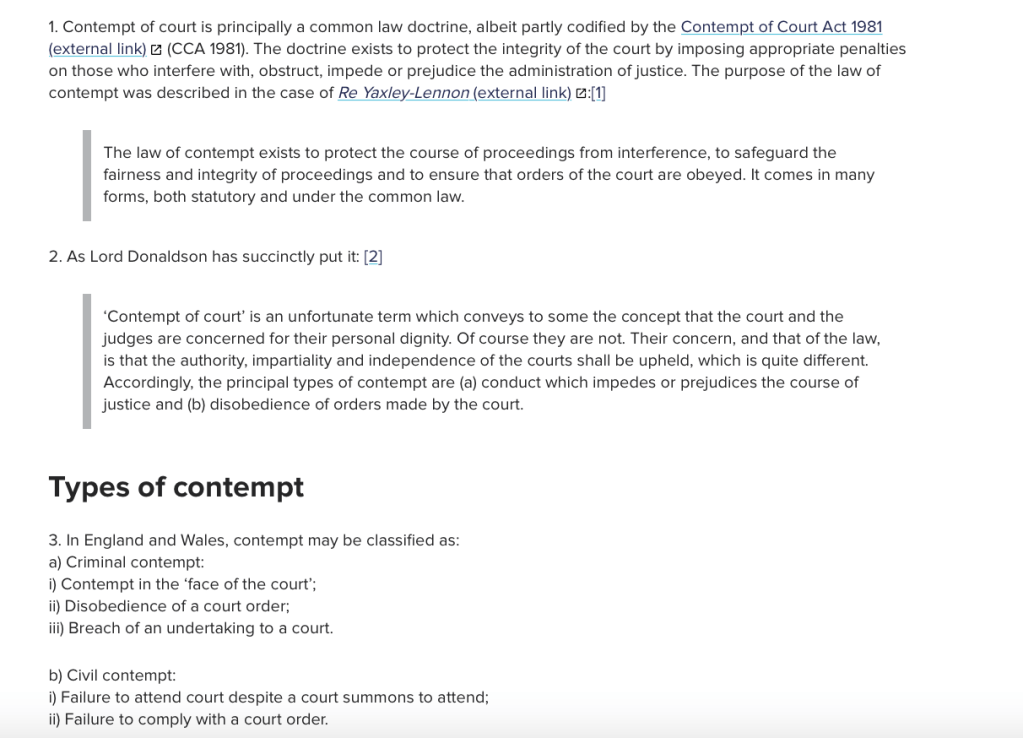

The Courts and Tribunals Judiciary defines contempt of court like this:

I have recently discovered, at a different hearing for contempt, that the criminal standard of proof (of beyond reasonable doubt) is required for both criminal and civil contempt. That is different to the usual standard of proof in the Court of Protection, which is the civil standard of proof: on the balance of probabilities (whether something is more likely than not), sometimes called the ‘51% test’.

The person committing the contempt is referred to as the ‘contemnor’ (or the ‘defendant’ in relation to their role in proceedings as a person against whom an application is made). The terms ‘committal hearing’ and ‘contempt hearing’ seem to be used interchangeably in the literature. I have used ‘committal hearing’ and ‘contempt proceedings’ in this blog.

The Open Justice Court of Protection (OJCOP) Project has blogged about several hearings involving contempt of court, here, here, here and here. Cases mostly involve family members or friends of P who are alleged to have breached the orders of the court. They might have contacted (or behaved in other ways towards) P contrary to court orders or revealed to others aspects of the Court of Protection case that they weren’t meant to, such as P’s name. They might have broken an ‘undertaking’ (a promise) that they made to the court.

It’s important for anyone caught up in Court of Protection proceedings to understand what can happen if they breach court orders or undertakings – and why what can happen ranges all the way from no penalty at all as in this case (and also in Esper) to immediate prison sentences of some months (potentially up to two years).

The case of Melvin Wright

On 3rd February 2025, Melvin Wright was found, by HHJ Hilder, to have been in contempt of court.

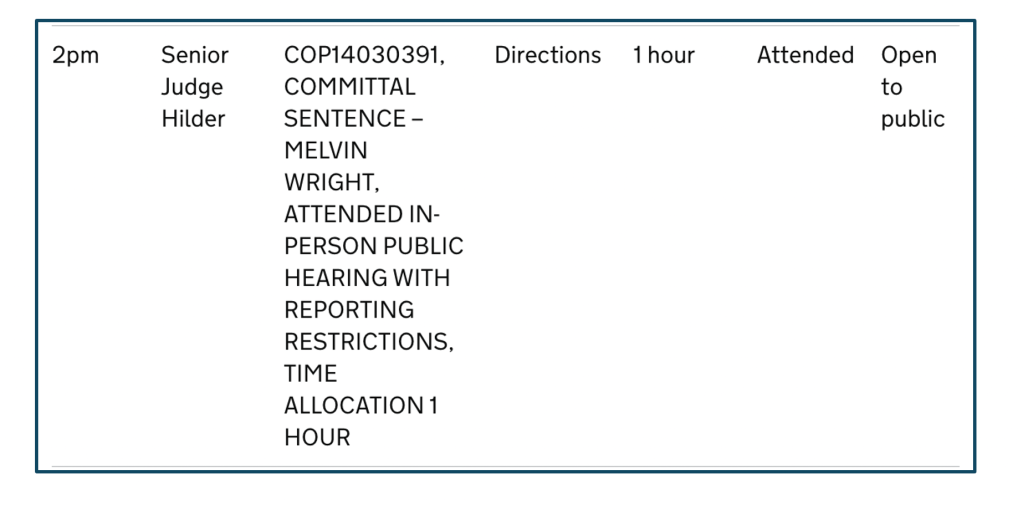

Sentencing was adjourned until 22nd April 2025. This was how the listing appeared on the First Avenue House website:

I blogged about the committal hearing here: “A named defendant awaits sentencing for contempt of court“. At that hearing, represented by Ben Harrison, Mr Wright admitted to four breaches of court orders:

- Allowing P into his flat (including overnight) in December 2024, unsupervised. He did not inform the Local Authority that she was there and the police located her.

- Replying to messages from P during the prohibited timeframe (which at the time was 6pm – 9am)

- Communicating with P about the Court of Protection proceedings

- Making reference to P’s sexual activities in response to messages that she herself sent Mr Wright about her sexual activities.

All of these acts are contrary to a court order served on Mr Wright in 2024.

In this blog I will report on what happened at the sentencing hearing. It’s important to say that I have not observed any of the welfare hearings in this case (which are about contact between P and Mr Wright, and about residence for P). So, I don’t know the context regarding restrictions on Mr Wright’s contact with P, why he is said to pose a risk of harm to her, or anything of the history of their relationship.

I didn’t really know what to expect of this hearing. I have observed one previous sentencing hearing, which was in person and I had been following the full case so knew a lot about the circumstances. This was different, and my involvement as an observer had started with the 3rd February 2025 hearing when (supported by the OCJOP Project), I submitted an application to ‘vary’ (change) the Transparency Order to permit the naming of the defendant. The previous blog details that process and why being able to publish the names of defendants in committal cases is an important part of open justice.

Before the sentencing

I was joined by three other observers (two remote and one who was at the hearing in person). The hearing started at 2.06pm and HHJ Hilder explained that P herself had no representation, her counsel having requested and been excused from the hearing by the judge. A legal official was instead present on behalf of P’s representatives, ‘on a noting brief’ said the judge.

Mr Wright was joined to the link from his home, and he was supported by a legal professional who was sitting beside him. He confirmed that he could hear the judge and he appeared calm and collected to an outside eye. Of course, he might well have been feeling extremely nervous, given that this was a hearing to sentence him for breaching court orders – which can be a sentence of imprisonment.

HHJ Hilder then noted the presence of observers, asking us all, one by one, to turn on our camera and confirm that we had received and understood the court order concerning “anonymisation of defendant” dated 3rd February 2025. Then she said: “To all observers, thank you for taking the time to observe today”. She also asked Ben Harrison (again representing Mr Wright) to send all observers a copy of his Position Statement for the hearing, to assist our understanding of proceedings. This was very welcome.

Ben Harrison drew the attention of HHJ Hilder to the legal framework for considering what sentence to impose, and also to case law in support of his submissions regarding mitigating factors for his client. I found the explanation of how a breach of court order might be assessed, and a sentence decided, very interesting (and was later supported in my understanding by the Position Statement which was helpfully emailed to me by the court clerk straight after the hearing). I know nothing about how these decisions are made and was wondering about the purpose of a committal and sentencing in a case such as this. Helpfully, Ben Harrison emphasised that “in civil contempt cases the focus is on ensuring future compliance”. So, the purpose of bringing such cases to court, making findings of contempt and sentencing the contemnor, is to try to make sure the person obeys the court orders in future.

What can the court do in relation to sentencing in the Court of Protection?

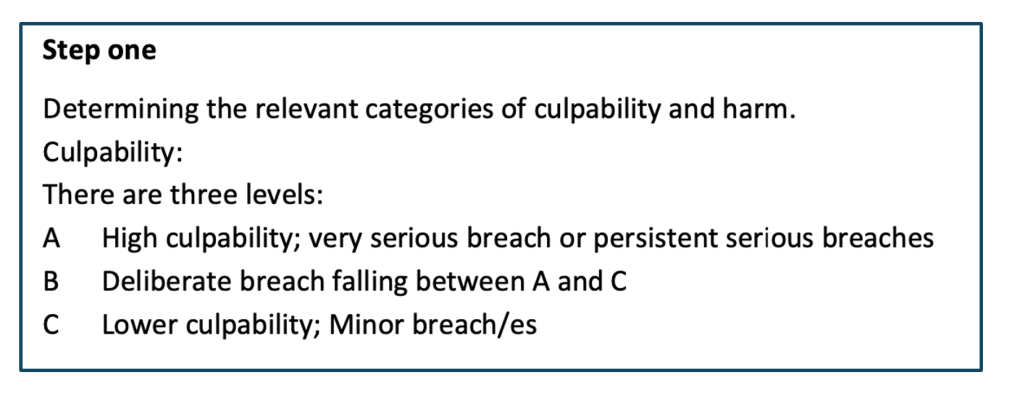

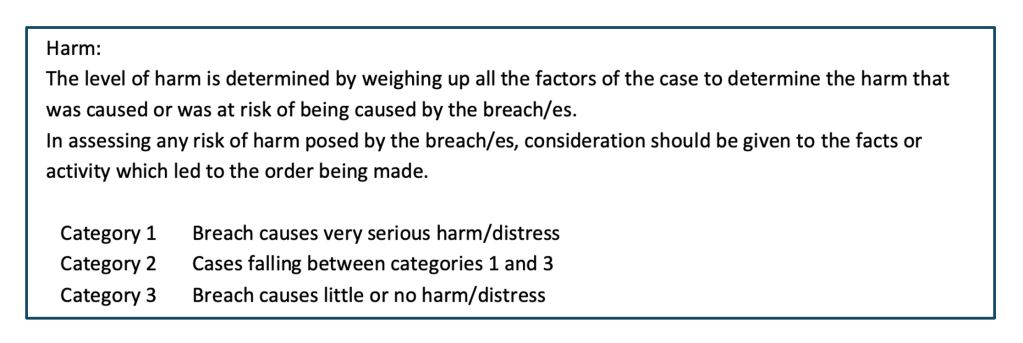

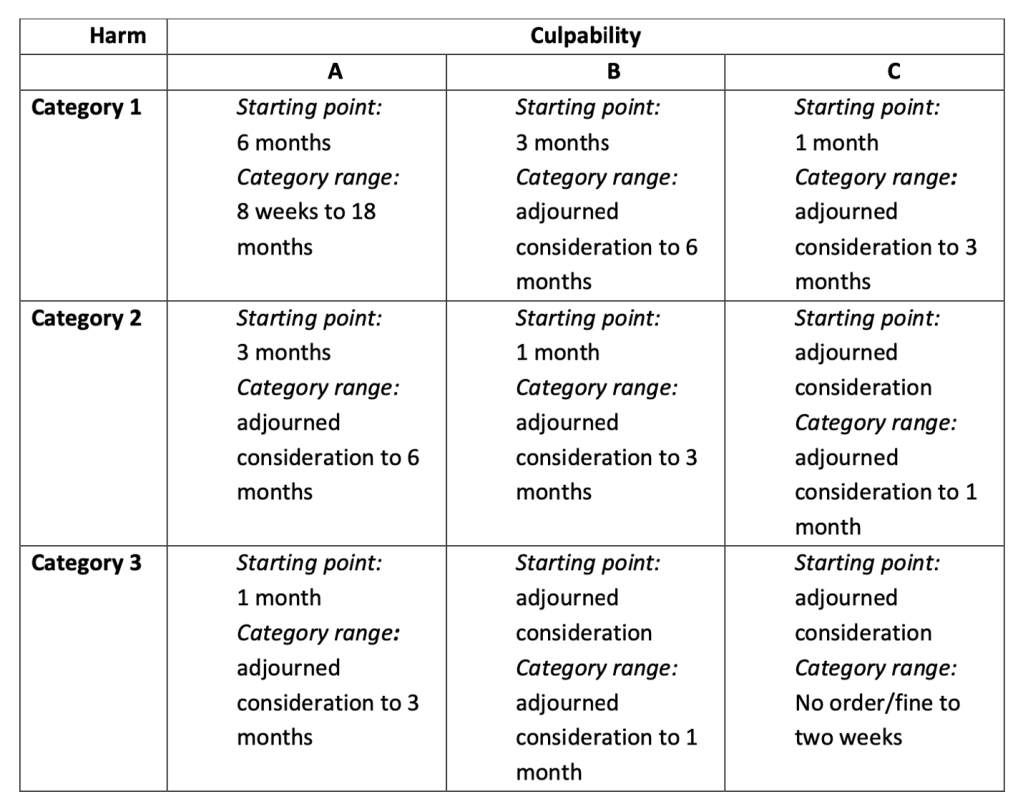

The relevant Act is the Anti-Social Behaviour, Crime and Policing Act 2014. There is Home Office ‘Statutory Guidance for Frontline Professionals’ (revised March 2023) in relation to the Act. However, Ben Harrison went on to describe a framework in the Civil Justice Council’s guidance document, entitled Anti-social behaviour and the civil court, dated July 2022. The first step is to establish the levels of culpability and harm:

On behalf of Mr Wright, Ben Harrison submitted that his client’s breaches fell into the following sections: Level C for culpability – ‘low culpability, minor breach/es’ and Category 2 for harm – ‘cases falling between categories 1 and 3’

Mr Harrison explained the position:

Mr Wright is 89 years of age, and he wishes me to emphasise that he loves P dearly. He had no intention to cause her harm or distress. That example is a Category 2 case: no intention to cause harm or distress. Addressing culpability in more detail and his witness statement from the last hearing – he takes 18 tablets including Tramodol, he can be more sleepy and forgetful, it makes it more difficult to comply with the court’s orders. He asks the court to take this in mind when considering culpability.

There are no supervision contact arrangements between Mr Wright and P at the moment: that’s been unsuccessful. When Your Honour handed down her judgment last year, the court had in mind that there would be some sort of supervision contact arrangements in place. Mr Wright has been willing to comply … without straying into other matters … I am not sure WHY these arrangements have been unsuccessful.

I believe he said to you he 110% supports the Local Authority package of care for P. His aim is to ensure P is kept safe. It is fair to say he is very much on a journey as to how he is to interact with P in order to help her. [….] Contact is to be restricted […] this is in tension with his concerns […] – if he turns her away he thinks she will believe he has abandoned her at this later stage in his life.”

Step two, explained Ben Harrison, is the ‘starting point and range of sentence’. The sentencing framework from the same document is replicated below. The ‘starting point’ suggested by counsel for Mr Wright was 2C: ‘adjourned consideration’ (which he acknowledged is what HHJ Hilder had already done at the previous hearing on 3rd February 2025).

According to the Civil Justice Council’s guidance document, there are five options open to a judge ‘when faced with a breach of an order under the 2014 Act’. These are:

- An immediate custodial penalty

- A custodial penalty which is suspended

- Adjourning punishment

- An unlimited fine

- No order

Ben Harrison explained to the court that, if Mr Wright’s breaches are deemed to sit in Category 2C (above) the options for the court ‘range up to one month imprisonment’, and that the court is ‘is entitled to take into account mitigation’.

In mitigation, it was submitted that Mr Wright is seriously unwell and under the care of a palliative care team. He regrets and repeats his apology to the court for the breaches; he has attended the committal hearings including when he was unrepresented; the Local Authority has not filed any evidence of further contempt since the committal hearing on 3rd February 2025. Mr Wright was said to have ‘abided by the court’s injunctions and proved himself capable of doing so in future’ – which is the purpose of contempt proceedings in the Court of Protection.

Ben Harrison emphasised that any sentence should be ‘just and proportionate’ and aligned with the guidelines. He had ‘impressed upon Mr Wright’ the need to comply with court injunctions and interestingly, suggested that ‘the process itself has secured […] his compliance and achieved the purpose of proceedings’.

I thought that Mr Wright’s counsel did a very impressive job, not only of summarising the legal framework and case law for the court, but of drawing together all strands of the committal part of the case, humanising the situation for the court on behalf of his client, and drawing attention to the messiness of contact arrangements that seem to have gone wrong through no fault of Mr Wright’s. At the time of the hearing, he was not in supervised contact with P, and there had been several aborted attempts.

HHJ Hilder asked about Mr Wright’s financial situation, which was not clear, but definitely not one of surplus income.

The ‘Sentencing’

HHJ Hilder was very stern and emphatic delivering the sentence. Perhaps that’s how all judges are when they are sentencing someone. It was clear she wanted Mr Wright to understand the seriousness of his breaches of court injunctions.

The judge has published her judgment here: Committal for contempt of court: London Borough of Camden v Melvin Wright & Ors [2025] EWCOP 14 (T2), and I also have my own contemporaneous notes on what she said in court, which forms the basis of the published judgment. This offers me the opportunity to check one against the other.

Comparing my notes against the published judgment, I’m pleased to see how accurate they are – albeit with bits missing because I couldn’t keep up with the speed of her delivery. I also have some observations that are not in the published judgment. For example –

Judge: Mr Wright – I am speaking to you directly as far as I can. Can you hear me?

Mr Wright: Yes I can, Judge.

That little piece of human interaction, which shows that the judge wanted to ensure that what she said was heard by the person it most concerned, is missing from the published judgment.

I also picked up features of the judge’s speech that don’t come across in the published judgment – particularly the stress she placed on particular words, as here:

Judge: Today I am concerned with the very serious matter of ensuring that court orders are obeyed. YOU have admitted breaching a court order, so I am considering what penalty should be imposed. Your barrister has very helpfully set out a summary of the legal framework that applies to the legal position [….] I adopt that framework and in particular Lovett against Wigan Borough, paragraph 33 of the judgment. I am reminded that the emphasis today is on the importance of ensuring that there is compliance in the FUTURE with court orders.

The judge then ran through the orders made on 21st October 2024 that Mr Wright had admitted breaching (in the published judgment those are §3 (the orders) and §4 (the admissions of breach), before summarising them preparatory to considering the penalty.

In the published judgment at §5 the judge says “[t]here are four heads of admission”, which sounds very legalistic. In the spoken judgment, my notes record her as saying: “So, four admissions have been made” – which both indicates (via “so”) that she’s summarising what has gone before, and is closer to ordinary conversational spoken English (though still in the passive tense, where “so, you’ve made four admissions…” would have been used to convey that she was (as she said earlier) addressing Mr Wright directly. Also, both in the written judgment and in the oral judgment in court, the judge described these admissions as “very serious”, but in my notes I have capitalised and bolded those words to mark emphatic delivery (“They include VERY SERIOUS admissions that you allowed P to stay at your flat).

I was pleased to note that I’d captured the two references to case law in §4.7 of the published judgment (Dahlia Griffith and Poole J in Macpherson). This was possible for me because I already knew of both cases and I’d watched the committal hearing before Poole J concerning Luba Macpherson and blogged about it here. For many court observers, the names of cases whizz by in an undifferentiated blur – as they did for me in the early days. But understanding the case law that judges rely on is very important for observers – and it’s another reason why we need to be supplied with Position Statements.

My version of what was said at the end of the judgment is virtually identical to the published version (§16 and §17), save for the fact that I noted the emphasis that HHJ Hilder put on the words ‘No Penalty’:

Judge: Finally, I bear in mind that it is proportionate and just that the sentencing for your breaches recognises the court’s preference to allow you an opportunity to end your life respectfully and for [P] to see that opportunity to be given.

In conclusion, regarding the finding of breaches made on the 3rd of February, today I formally impose NO PENALTY for those breaches. The injunctions stand. This court expects you to conduct yourself now in such a way that no further committal proceedings will be required.

The judge checked with counsel for Mr Wright whether there was ‘anything arising from that?’. And Tony Harrop-Griffiths (representing the Local Authority, the London Borough of Camden) confirmed that ‘in general terms’ the Local Authority did not disagree with the sentencing.

Ben Harrison had asked the court to consider a couple of other issues – which I won’t report on here – and indeed the judge (whilst agreeing to briefly address them) said that ‘generally speaking we try to keep committals separate’.

And with that, HHJ Hilder said ‘Mr Wright, thank you and good afternoon’.

Mr Wright looked quite surprised at the sudden departure and said ‘You have gone!’.

The hearing lasted 49 minutes.

Reflections

As I said at the start of the blog, I haven’t observed any of the welfare hearings in relation to this case. So, I don’t know what are said to be the risks of harm to P from Mr Wright. I don’t think I am in a position to comment on the fact of contempt allegations being brought against him, or the committal and sentencing of this man.

It has become clear to me, from the two hearings in the committal element of the case, that P’s situation is complex and Mr Wright sometimes finds himself in situations with P that are not of his making. This mitigating factor, along with others such as Mr Wright’s admission to the breaches, the current and ongoing obeying of court orders and his health status, were taken into consideration in the judge’s sentencing.

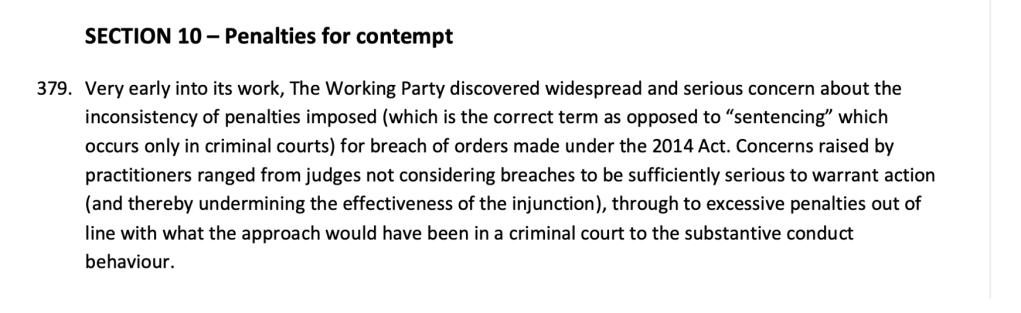

The guidance from the Civil Justice Council referenced earlier, discusses the Working Party’s findings into the consistency of penalties for anti-social behaviour in the civil courts (the word ‘sentencing’, I now realise from this helpful document, is applicable only to criminal courts, and the word ‘penalty’ should be used for civil contempt):

It is of legitimate public interest to know about penalties imposed for contempt of court in the Court of Protection, including the range of penalties imposed, whether they are consistent across cases (although, as the guidance makes clear, each case has to be weighed on its own facts) and how many contempt of court cases (with and without penalties) are decided in the Court of Protection. As we said in our submission to the Ministry of Justice Law Commission Consultation on contempt of court, the lack of systematic data collection about contempt proceedings and the failure to publish Transparency Data in relation to contempt of court is “clearly a problem for a court with aspirations to transparency and should be remedied immediately” (“Contempt of court proceedings: Are they transparent?”, section 2)

Claire Martin is a Consultant Clinical Psychologist, Cumbria, Northumberland, Tyne and Wear NHS Foundation Trust, Older People’s Clinical Psychology Department, Gateshead. She is a member of the core team of the Open Justice Court of Protection Project and has published dozens of blog posts for the Project about hearings she’s observed (e.g. here and here). She is on X as @DocCMartin, on LinkedIn and on BlueSky as @doccmartin.bsky.social