By Amanda Hill, 11th August 2025

Update 30th September 2025: The OPG have now issued a press statement summarising what deputies should do and an address to contact Motability. You can read about it here:

Update 2nd September 2025: I’ve now received a copy of the approved order for this hearing so I’ve added a section at the end of the blog with the relevant information

Working like clockwork. This implies each small part moves in precise harmony to keep the larger system functioning. Wouldn’t it be wonderful if the state was like that? I’ve recently observed a hearing that reflected the exact opposite.

Deputies, both lay (mostly family and friends) and professional, play a crucial role managing property and affairs for vulnerable people. They experience a lot of difficulties at the coalface, and leading up to the hearing I observed, many different components combined to create a problem that nobody seems to be able to solve and nobody is taking responsibility for.

At the centre of this hearing was Deborah Pardoe, CEO of AST, Allied Services Trust, which is a deputy as a Trust Corporation. She’s doing her best to highlight significant problems but coming up against “the system” – or rather different parts of the system: human, legal, digital, governmental. She’s ended up frustrated and disappointed that she couldn’t achieve the outcome she wanted, in spite of the achievements that did result.

At its heart, the issue at stake in this hearing was a risk that Deputies for Property and Affairs face (as do professional and lay attorneys) . But more fundamentally than that it highlights that a Deputy for Property and Affairs really has nowhere to turn to for support and advice, nobody who will take up an issue on their behalf. They are appointed by the Court of Protection and supervised by the Public Guardian, but neither the court, nor the Public Guardian provide deputies with support: that’s not their function. And deputies don’t have power over other parts of the system that impacts how deputies function. That’s the backdrop to this hearing.

Deborah was the applicant in this case, for and on behalf of AST, and she was a Litigant in Person. She wanted to highlight a risk faced by deputies and was trying to find a way of eliminating that risk. She had identified a flaw in in the system, and wanted it changed. The power of the Court of Protection is circumscribed – it couldn’t do what she wanted, but the case shows the court can nevertheless be used to facilitate solutions to seemingly intractable problems.

The flaw in the system she was concerned about concerns Motability Hire Agreements. These agreements clearly expose deputies, both lay and professional, to personal and professional risk. She applied to the court over two years ago now to try to seek a remedy for the flaw, not just on her behalf but on behalf of the thousands of other lay and professional deputies she believes are impacted by this issue. She has been persistent in her application and it’s now being considered before the President of the Court of Protection, on 18th July 2025.

In this blog I’ll first outline the specific problem with Motability Hire Agreements that led to this application[1] and then set out what happened at the hearing. I’ll end with the Deputy’s reflections on her experience

1. Motability hire agreements

The background to this hearing is quite technical but has important legal implications. Many of you may have heard of the Motability Scheme. This allows the higher mobility element of certain benefits such as Disability Living Allowance (DLA) and Personal Independence Payment (PIP) to be exchanged to lease a vehicle. Anyone eligible for a Motability vehicle must enter into a legal agreement with the Motability Scheme. If, however, someone lacks capacity to manage their property and affairs, then someone else with the necessary authority such as a deputy, an attorney or an appointee must sign the agreement on their behalf.

Deputies for Property and Affairs are appointed by the Court of Protection, to manage the property and affairs of the protected party ‘P’. Section 19 (6) of the Mental Capacity Act states that a deputy for property and affairs is P’s agent: “A deputy is to be treated as P’s agent in relation to anything done or decided by him within the scope of his appointment and in accordance with this Part”. Therefore, when a deputy (acting within the scope of his authority) contracts with a third party on behalf of P, they do so as agent for P and not as principal under the contract. However, the contracts issued by Motability treat the deputy as “hirer” and impose obligations upon them as if they were the principal under the contract and not the agent of P. Insurance issued in respect of a Motability Vehicle is issued on the basis that the deputy, and not P, is the insured party.

This leads to a risky legal position for the deputy. It is common for Motability vehicles to be driven by someone other than the hirer, such as carers or family members of the person who lacks capacity. There are concerns that if a deputy is named as principal on the lease agreements, the deputy becomes liable for the actions of the drivers and users of the vehicles. For example, any claims on insurance would be made against the deputy and any offences committed by the driver, such as speeding, would in the first instance be charged to the deputy. AST have highlighted further concerns that any claims could affect the deputy in obtaining their own personal insurance or professional indemnity insurance.

The underlying problem is compounded by outdated government IT systems and the way Motability systems talk to them. The current IT system operated by the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) cannot record a status of “deputy for property and affairs appointed by the Court of Protection”[2]. The DWP computer system is unable to distinguish between a deputy, attorney or appointee. Motability can only act on information recorded by the DWP. Because of this, Motability systems cannot recognise that a deputy for property and affairs acts for P as agent and not principal, and do not distinguish between the legal status of agent and principal.

The consequences of this situation are that a P may not get a vehicle to which they are entitled (if a deputy refuses to sign the agreement due to the risk involved) or the deputy signs the agreement and is faced with the risks outlined above.

AST acts as corporate deputy for property and affairs, appointed by the Court of Protection, for their client, the protected party ‘SS’. When AST became aware of their risky legal situation, they informally contacted the Ministry of Justice (MOJ), the DWP, Motability and Motability’s insurers to achieve a solution. Although Motability put in place a manual workaround, according to Deborah Pardoe, this wasn’t fit for purpose.

Therefore, on 28 April 2023, AST applied to the Court of Protection in relation to SS to try to obtain an order for Motability and its insurers to recognise the status of a deputy and to record the deputy as an agent rather than the principal.

The wheels of justice moved slowly and it wasn’t until 20 December 2024 that the court gave directions that Motability, the insurers, the DWP and the MOJ should seek to resolve the issues and report back to the court. No resolution was forthcoming, however, and on 23 April 2025, the court directed the Public Guardian to provide a report to aid discussions. The Office of the Public Guardian is an executive agency of the Ministry of Justice and its role is to support and supervise deputies, investigate concerns, and safeguard people who lack capacity.

AST applied to the court to progress matters. §5 of the PS from the DWP states: By a COP9 dated 19 June 2025 AST invites the court to join the various organisations involved as parties to these proceedings. AST seeks orders (a) directing Motability and Royal Sun Alliance (or any other insurer) “to acknowledge the Court Order appointing Allied Services Trust as Property and Affairs Deputy for SS” and (b) to direct Motability to “issue a Motability contract and insurance policy in the name of the client SS and not AST”; (c) to direct the DWP to record AST as a Court Appointed Deputy and not an appointee. (For clarification, Motability cars are now insured by Direct Line, who took over from Royal Sun Alliance in 2023).

According to §14 of the PG’s PS, Senior Judge Hilder listed the application for a hearing before the President of the Court of Protection. The court’s order of 23 June 2025 states:

“the court considers that

a) the ability of DWP to give proper recognition to deputyship status and

b) the engagement to date/willingness of the Office of the Public Guardian to engage with systemic problems in the operations of deputyship are matters of such significance that they ought to be considered further by the Court.” (my emphasis)

The positions of the DWP, Motability and the Public Guardian

Reading the position statements (PS) of the organisations involved provided me with valuable insight into issues about jurisdiction.

A major factor affecting this hearing was the relationship between the organisations and the power of the Court of Protection over those organisations. The DWP is responsible for transferring mobility allowances to Motability Operations Limited (MOL). MOL is an independent company but its systems rely on information provided by the DWP. The Ministry of Justice funds and oversees the Office of the Public Guardian, and is responsible for the operation of the MCA 2005, but has no role in the administration of the Motability scheme. The DWP is completely separate to the OPG. The Court of Protection (CoP) is responsible for making decisions in the best interests of P if they are found to lack capacity. The CoP, although it appoints a deputy for property and affairs to act in P’s best interests, has no responsibility towards the deputy. MOL and the DWP do not believe that the court has jurisdiction to order them to do anything.

The nub of the issue was that the court could not order the DWP, or Motability, to act. And the OPG had limited responsibility for the problem too. The court was effectively being used to facilitate a resolution to the problem. And the applicant was faced with a problem to which there was no easy solution, and nobody was accepting responsibility for solving it. §13 of the Public Guardian position statement states “the issue appeared to relate to the internal processes of the various bodies concerned”. Processes need to be improved – but what can be done?

The DWP is refusing to change its IT system. §7 (b) and (c) of the DWP PS states that “the amendment to the computing systems that AST anticipates would be a substantial piece of work that the DWP is not in a position to effect at this time; and a proportionate, pragmatic approach as proposed by Mobility Operations Limited should be put in place”.

Motability have acknowledged that there is an issue with its current IT systems but also assessed that it would be too difficult to change their IT systems. However, they can use a “manual work around”. This can be done as long as the DWP can confirm that P is in receipt of the relevant qualifying benefit. Therefore, it still involves the DWP and MOL communicating.

The manual workaround that was trialled in early 2023, between AST and MOL, with the contract being manually altered to show P as the principal did not work, as information was not disseminated to the Insurance Provider, the DVLA and other third parties. When the details were altered on the IT system, it meant that all correspondence would be sent to P, and not the deputy. So, the IT system changed the principal back to AST.

The new workaround agreed at this hearing is to show “P as the principal, by his/her Deputy” detailing the deputy who is named, and the AST address used for correspondence. The contract also records P’s address as the registered owner. This information can be retained on the Motability IT system and can be sent to the insurance provider, DVLA etc (which was not happening previously).

I also note from the position statements that the Public Guardian did not wish to be joined as a party to proceedings. The DWP submitted in its position statement that it was not desirable for it to be joined as a party. I couldn’t find any reference in the PS for MOL as to its position on being joined as a party. I understand that the Ministry of Justice and the Insurance Company for Motability (Direct Line) were invited to attend the hearing but didn’t.

2. The hearing

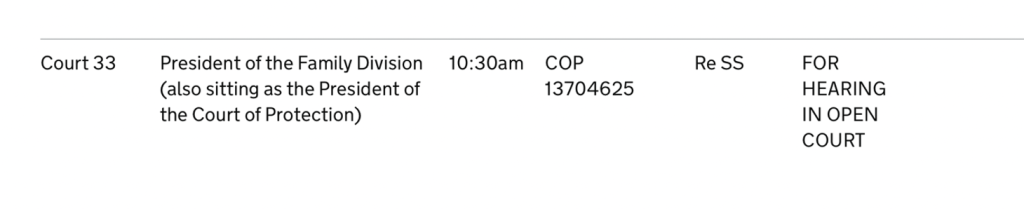

The hearing for COP 13704625, Friday 18th July 2025, was listed on the Court and Tribunal Hearings (CaTH) as follows:

“SS” is the P who ATS acts as deputy for. In common with most Royal Courts of Justice listings, the substantive content of the hearing was not indicated. I had no idea what the hearing would be about but as I haven’t observed a hearing before the President and I happened to be in London for another hearing that day, when I saw the listing the evening before, I decided to observe in person.

I arrived at the Royal Courts of Justice in good time for the hearing and made my way up the grand staircase in the West building to the 1st floor, where I knew Court 33 was located. I could see a number of people around a table just in front of the courtroom. I gathered that they were in some sort of discussion before the hearing. They were discussing a draft order but apart from that I wasn’t actively listening and couldn’t hear what they were saying anyway. When the courtroom door opened at 10.20, they all made their way in and I followed them. I approached the clerk at her desk and said that I wanted to observe the hearing, asked for a copy of the transparency order (TO) so that I understood the reporting restrictions and mentioned that I would like a copy of the parties’ position statements. In a short time, I had received a hard copy of the position statement from the PG and MOL. Counsel for the DWP asked me for my email address and sent it to me immediately. This is in line with guidance in Poole J: AB, Re (Disclosure of Position Statements) [2025] EWCOP 25 (T3). I also received a hard copy of the TO from Counsel for the PG. I really appreciated being given the position statements so quickly once I had entered the courtroom but I didn’t have time to read them before the hearing started, so I didn’t understand what it was about.

The hearing began when Sir Andrew McFarlane, President of the Court of Protection, entered the courtroom just after 10.30am and without any preamble, addresses “Miss Pardoe” and asks her to speak as “it’s your application”.

Deborah Pardoe, appearing as a Litigant in Person, started to say something about the application. After a short while, David Rees KC representing the Public Guardian stepped in and offered to do the introductions. The other representatives were: Nicola Kohn 39 Essex Chambers representing the DWP and Eliza Eagling 5 Stone Buildings representing MOL.

The judge didn’t acknowledge me at all during the hearing and he didn’t do anything to make me feel particularly welcome. There was also no summary for my benefit as advised by the former Vice-President, Mr Justice Hayden (“The Court of Protection and transparency”). These points are listed in our blog Fifteen Top Transparency Tips for Judges. I hope it’s not going to be the case that now that judges are aware that observers are likely to be provided with position statements (PSs) they will be less willing to allow time for a summary. We still need an opening summary since PSs are often sent so close to (or after) the time of the hearing that we don’t have time to read them by the time the hearing starts, as was the case with this hearing.

I must admit, sitting at the back I found it quite hard to hear in places, and difficult to follow. There were no microphones. I remember thinking that I was glad I would have the PSs to read afterwards. I’ll do my best to give a flavour of what I heard and understood. The hearing proceeded as follows:

The judge states that he has been given a draft order and asks if it has been agreed. Ms Pardoe says not all of draft order has been agreed. The judge comments that the CoP understands the jurisdiction issue, repeats that a draft order has been agreed and is about a deputy not being named principal in the hire agreement. The judge then asks Ms Pardoe what jurisdiction the Court of Protection has to order the DWP to do something. Ms Pardoe replies “I don’t know, that’s why I’m asking the court”. The judge states that no court has jurisdiction and asks her “did you take legal advice?”. Ms Pardoe replies something about the DWP that I couldn’t catch.[3] Counsel for the PG then speaks and says that they have had a meeting outside the court. The CoP has limited powers when it comes to public bodies (he must include MOL as a public body even though technically I don’t think it is, as it’s a limited company), as it makes decisions on behalf of P. It is proposed by the organisations that Motability (MOL) change the hire agreement so that the P will be the principal and they will update all bodies including DVLA. (I think this refers to the revised manual workaround).

There was some technical discussion that I couldn’t follow at this point.

The judge then states that the order isn’t agreed. It is agreed by the public bodies but not the applicant. The collective case is that the court has sympathy for her position but that there is no remedy the CoP can order. Counsel for the PG states that there has been constructive discussion, and that the matter has been before the CoP for some time.

“Two years” the judge states baldly. He then asks how the order can be publicised to deputies. Counsel for the PG replies that court orders are not usually published on their website. The judge states again that it would be useful for “some sort of public recital” to go out so that there is wider publicity for deputies and MOL: “If some good is going to come out of this, it needs to be publicised so people in future won’t (be uninformed? )…I am grateful to the PG for co-operating with this process”.

He then speaks to Counsel for MOL, asking her about manual entry to the system. She states that it may take some time for the process to be automatic, for MOL IT to be able to speak to DWP systems and that may stop a disabled person from receiving a vehicle ….so there would have to be the manual workaround. Other deputies should know who to contact (at MOL). The judge states that it is good to know that efforts can be made to alter Motability systems and he is grateful to Motability.

He then turns to Counsel for the DWP but as she doesn’t have a microphone and I am sitting right behind her, I can’t hear what she says in reply.

The judge then says: “Miss Pardoe, what further do you wish me to do?”

Ms Pardoe states that steps have been agreed and are a significant improvement. She then asks “As a deputy who do we go to for support with this sort of matter? The OPG are helpful but there are areas as a deputy that ….(I can’t hear).”

There was then the following exchange about who a deputy could turn to.

Judge: …and you feel you are being fobbed off without an easy avenue to resolve….

Ms Pardoe: This isn’t about P, it’s about being a deputy and discharging their role.

Judge: “But that’s not a role for the CoP, and what have you achieved now compared to two years ago?

I felt there was an implicit criticism that by following through with the application, she had wasted the court’s time. But it was Senior Judge Hilder who had referred the matter to the higher court, so presumably Senior Judge Hilder must have felt that something more could be done.

Ms Pardoe replied that the previous workaround “didn’t work” so the proposal made, if it worked, would be an improvement. The judge asks her if she is content for the court order to say the applicant is content, as well as the public bodies. I think she agrees. She asks about the delay in the roll out of the manual work around. Counsel for MOL replies that Motability is contacting its IT teams but can’t promise anything with regards to timelines. She mentions a special team is in place. The judge agrees to add a sub-paragraph to the order that mentions the “best endeavours” of Motability to deal with the issue quickly for individual applications.

The judge concluded by saying that the “court having no power to do anything has achieved something by bringing everyone together”.

The judge then rose just before 11am. The hearing was over after just under 30 minutes.

Counsel stayed in the courtroom and were talking about how to publicise the workaround more widely. I then realised that they were looking at me and mentioning whether a blog could be published. I said that I didn’t think that would be a problem.

One difficulty I have encountered in writing this blog is that I haven’t received a copy of the approved order, because it hasn’t been sealed yet. The draft had to be amended and holidays are slowing things down.

I understand though that the approved order places the onus on an attorney or deputy to contact Motability to request the workaround. Motability will use its “best endeavours” to apply the Manual Amendment to the hire agreement. (section v of the order).

3. Reflections from the applicant

I contacted Deborah Pardoe after the hearing, in order to make sure that I had understood everything correctly.

She has been advised that the Public Guardian is working with external communications and stakeholder engagement teams for the order to be advertised as soon as possible so that deputies know about the workaround. She said that this situation has raised the question of who a deputy or attorney can go to for quick effective and efficient help and support.

She also told me “I wanted to ensure that those working for and on behalf of the vulnerable of society are protected, by a correct working practice, and the correct recording of a deputyship appointment, and importantly for the Law from which those attorneys and deputies hold appointment to be respected by third parties”.

I asked her what she thought had been achieved from the process. She is clearly frustrated and disappointed that the onus is still on the deputy or attorney to contact Motability. She said that many deputies aren’t aware of the risk. What, for example, would happen if somebody was killed by a Motability car driver and the agreement was with the Deputy?

When I asked her what she thought she’d achieved, she summarised it like this:

“What has been achieved?

- A temporary revised manual workaround.

Although the opportunity to have a defined timeline on how, where and when that workaround will be put in place was lost.

- Recognition by Government Departments and Motability that there is an issue with the current DWP and Motability IT systems that do need to be addressed.

- Motability now acknowledging the Deputyship Order rather than relying on incorrect information supplied by DWP.

However, Motability have no requirement to evidence that processes discussed at the hearing will actually be implemented, “best endeavours” is a woolly term and non-committal.

- Awareness that there appears to be no effective and efficient system to provide support to deputies or attorneys, hence the reason the case was taken to the President.

Whilst the above achievements are progress, there remains the disappointment that the Court did not use the opportunity of the hearing to go further to protect the position of the deputy.

This case was not about the Court requesting third parties to make changes for P, (case law relating to this stance was heavily relied upon during the hearing) it was about the Court requesting that the DWP and Motability acknowledge and respect the Deputyship Order appointing a Deputy. This case was about the Court itself being respected, and for those working on its behalf to be protected.

Simply, the Court of Protection make decisions to protect the vulnerable of society, the Public Guardian is required to oversee those decisions. How then, can the Court of Protection and the Public Guardian have no ability to protect those working for and on behalf of the Orders that the Court have made?

The hearing was brought before the President because of the lack of proactive engagement and resolution from those attending the hearing (and the Ministry of Justice and Direct Line who elected not to attend) and lack of support to the deputy from the Public Guardian in the two years leading up to the 18 July 2025. HHJ Hilder gave all parties opportunity to engage.

Whilst the Public Guardian is in the process of arranging for the order to be published/advertised, following the hearing, the where, when or how the Final Order is to be published/advertised to support all those involved with Motability Vehicles is yet to be mentioned. Motability were not requested to evidence any advances they make to their internal systems to the Public Guardian. Further the onus will currently remain upon the deputy, attorney or appointee to request the manual workaround…… but how can anyone ask for something if they do not know there is something to be asked for!

As a result, the many thousands of deputies, attorneys and indeed appointees currently remain working at risk.

A little tongue in cheek…… This case can be summed up as follows:

Everybody, Somebody, Anybody, and Nobody

A team had four members called Everybody, Somebody, Anybody, and Nobody. There was an important job to be done. Everybody was sure that Somebody would do it. Anybody could have done it, but Nobody did it. Somebody got angry about that because it was Everybody’s job. Everybody thought Anybody could do it.

Nobody realised that it’s Everybody’s job. Everybody wouldn’t do it. It ended up that Everybody blamed Somebody when Nobody did what Anybody could have done.”[4]

Sections from the approved order dated 18th July 2025 (added to blog 2nd September 2025):

AND UPON the Applicant, Public Guardian, Motability and the Secretary of State for Work and Pensions agreeing and the Court recording that:

- The Applicant is a Trust Corporation for the purposes of s.64(1) Mental Capacity Act 2005 and s.68(1) Trustee Act 1925.

- A person appointed as a deputy for property and affairs for P pursuant to section 16(2) of the Mental Capacity Act 2005 is, in accordance with s.19(6) MCA 2005, to be treated as P’s agent in relation to anything done or decided by the deputy within the scope of its appointment and in accordance with the MCA 2005.

- Accordingly, the Applicant, in acting as deputy for property and affairs for SS is to be treated as SS’s agent.

- Motability agrees to manually amend (“the Manual Amendment”) the hire agreement in the cases of SS and those other individuals in respect of whom the applicant acts as deputy for property and affairs and to recognise and name SS (or as the case may be the individual for whom the applicant is acting as deputy) as hirer thereunder (the manual amendment on Motability’s IT systems automatically generates an update to relevant third party service providers including the insurance provider and DVLA).

- Motability will use its best endeavours to apply the Manual Amendment to the hire agreements in respect of other individuals who are acting by their deputy or attorney under an enduring or lasting power of attorney upon request from the said deputy or attorney, as the case may be.

- Motability agrees to take steps to ensure that the status of a property and affairs deputy as agent for “P” (and the status of an attorney under a Lasting Power of Attorney as agent for the donor of the power) is understood and recognised by its organisation.

- The represented public bodies agree that the resolution of the IT difficulties as between Motability and the Secretary of State for Work and Pensions is a policy decision that falls outwith the powers of the Court of Protection.

AND UPON the Secretary of State acknowledging that her use of the terms “appointee” or “corporate appointee” as a badge on its IT system, Searchlight, may cover appointees, attorneys under enduring and Lasting Powers of Attorney (under Schedule 4 and s.9 Mental Capacity Act 2005) and deputies (under s.16 Mental Capacity Act 2005).

Amanda Hill is a PhD student at the School of Journalism, Media and Culture at Cardiff University. Her research focuses on the Court of Protection, exploring family experiences, media representations and social media activism. She is a core team member of OJCOP. She is also a daughter of a P in a Court of Protection case and has been a Litigant in Person. She is on LinkedIn (here), and also on X as (@AmandaAPHill) and on Bluesky (@AmandaAPHill.bsky.social)

Footnotes

[1] I am very grateful for the receipt of position statements from the represented organisations who attended the hearing: The Department for Work and Pensions, the Public Guardian and Motability Operations Limited. I also received some information after the hearing from AST, who did not write a formal position statement. They submitted a summary and request for decisions to the Court. These have all helped me to understand this hearing better and enabled me to increase the accuracy of my reporting. I have heavily relied upon these documents, especially for the background to the hearing.

[2] Only AST have tested this in court in relation to their client SS in COP13704625. But the issue is believed to be much wider.

[3] Deborah Pardoe told me afterwards that she had spoken to a lawyer informally but was worried about legal costs to the charity of obtaining formal representation. They offer their services on a not-for-profit basis.

[4] Anonymous poem, widely attributed to Charles Osgood: Osgood, C. (n.d.). The responsibility poem. In Apple Seeds: Inspirational quotes and short stories (J. Bartley, Ed.).

I am in exactly this position as the appointee for my son. I spoke to direct line and motability today 06.12.25 who both stated I am liable for the agreement and the insurance as the policy holder / appointee. I am unsure of the process to get myself named as the person acting on their behalf but will try to use the references in this post to do just that.

LikeLike