By Jenny Kitzinger, 11th September 2025

Mr R is a 72-year-old man who has a psychiatric illness and appears to have an (unidentified) underlying neurological condition which has contributed to rapid mental and physical decline over the last two years. He is in end-of-life care and expected to die within days. He was the protected party at a hearing (COP 20020839) I observed remotely on 2nd September 2025 at First Avenue House before DJ Mullins. It was listed as a directions hearing about a statutory will.

A statutory will is a last will and testament authorised by a judge in the Court of Protection when the protected party lacks capacity to make a will themselves, and when it is in their best interests for the will to be made. There’s more information in a blog post by a lawyer: “Statutory Wills: A barrister explains” and a blog about a different case here: “Judge approves statutory will in contested hearing”. For an example of academic analysis of statutory wills and discussion of case law see “Doing the right thing under the Mental Capacity Act 2005”

I’m personally interested in wills as I’ve just completed an arduous process of being executor for the will my father wrote, and I’m particularly interested in statutory wills because I’m a lay Deputy for Property and Finance for my brain-injured sister, Polly Kitzinger. My deputy role means that I have responsibility for ensuring that decisions Polly’s unable to make for herself are made in her best interests. A Deputy cannot make a will for the person they act for, but they can make an application for the court to do so, and they (or anyone concerned for the person’s welfare) can draw up a draft will for the court to consider.

Most statutory wills are approved by the court without a hearing. They are not problematic – nobody contests them. So there are not very many opportunities to observe hearings and I was pleased to be able to get to this one.

Background

Despite the fact that Mr R has been found to lack capacity to make a will, he is still able to communicate his views about the sort of will he wants. He used to be married (now divorced). He has a son and daughter from that marriage who he’d like to be executors of his will and to inherit everything.

He also has an ex-partner who used to live with him. He’s told his children, and separately also said to an independent social worker and a solicitor, that he does not wish his ex-partner to receive any benefit from his estate. (His main asset is a relatively modest house).

The problem is that Mr R’s existing will, drawn up in 2014, makes his then-partner co-executor (along with his son) and doesn’t name his daughter as executor. The 2014 will may also still give his ex-partner some claim to live in his house (as she was doing when he wrote the 2014 will). This claim may be (at least theoretically) possible despite the fact that the relationship ended soon after Mr R first became unwell. A few months after he was admitted to hospital (in Autumn 2023), she moved out of his house, ended the relationship and returned to live in a house she owns. They’ve not seen each other at all now for well over a year, and Mr R is clear that he does not want to see her.

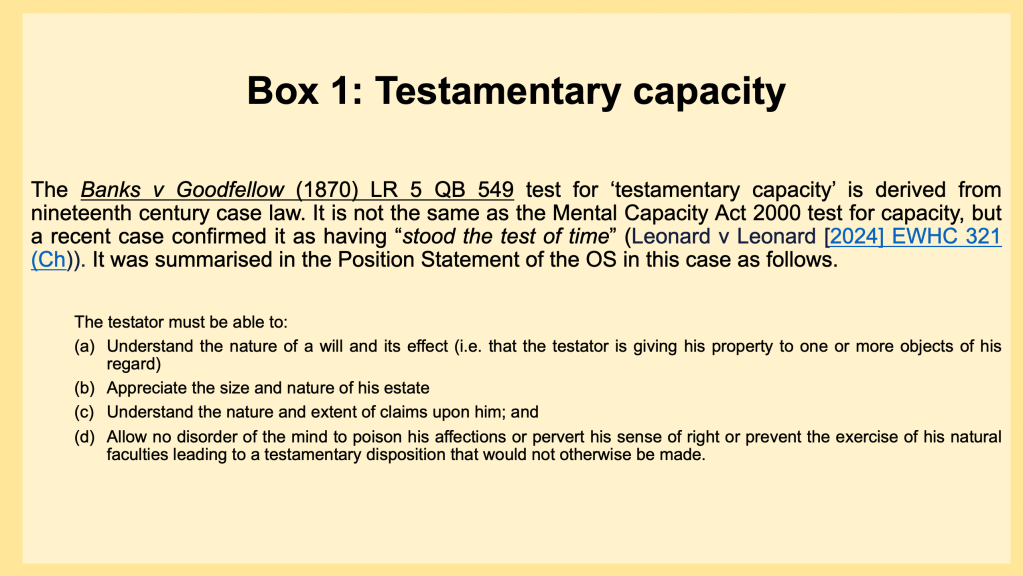

Many people in this situation might make a new will – but Mr R cannot do that because he now lacks ‘testamentary capacity’. He understands the nature of his relationships (e.g. that his ex-partner is no longer in his life, and the importance of his children to him) and he’s clear about what he wants to happen in terms of inheritance. However, when visited in hospital and subject to a formal capacity assessment, he said that he thought his assets were “worth nothing” and that his house was “gone”- so it has been determined that he does not understand the nature and extent of his estate, which is one of the key tests for ‘testamentary capacity’. (See Box 1)

This is the context in which an urgent application to the Court of Protection has been made by his children for a ‘statutory will’ – a will authorised by the court in the best interests of a protected party.

The statutory will they propose would remove Mr R’s ex-partner as co-executor and also take out any reference to her rights of occupancy. This would allow Mr R’s children to inherit the house, as they would have done anyway, but ensure this was free from any potential claim from the ex-partner in regards to living in the property.

I do not know the views of the ex-partner on all this as she was not represented in court, and had submitted no response since being notified of the hearing and served with the relevant papers. Her sister had sent a text message to Mr R’s son saying that no response could be expected from the ex-partner until she’d had time to seek legal advice.

This was an upsetting set of circumstances for all concerned – with time, money and stress being devoted to the issue of inheritance as a man lay dying, and it was clear that the case was very urgent indeed.

The hearing

Counsel for the applicant son and daughter was Jennifer Lee, Pump Court Chambers (and Mr R’s daughter was also present online, sitting with her solicitor.)

Counsel for Mr R, by his litigation friend the Official Solicitor was Georgia Bedworth of Ten Old Square

There were very clear and helpful position statements (written the day before), which I’d been sent in advance along with the Transparency Order (in compliance with the guidance from Mr Justice Poole in Re AB).

The position statement from applicants sought an order for authority to execute the Statutory Will for Mr R emphasising that the state of his health made the matter urgent. If the Court was unable to do that (e.g if the ex-partner submitted objections that left the judge of the view that there was doubt about Mr R’s best interests), they wanted an interim order authorising execution of the proposed statutory will (as a holding position) to be followed by an urgent contested hearing.

The OS agreed with the applicants that it was in Mr R’s best interests to authorise a statutory will in the terms proposed. In her position statement the OS noted that as yet no response had been received from the ex-partner – and that it was possible that she might dispute some of the facts – but that Mr R’s wishes and feelings, “which were expressed in the absence of either of the Applicants” were “a factor of magnetic importance in assessing Mr R’s best interests”.

At the hearing there was still no information from the ex-partner and she did not attend.

A draft order agreed between the applicants and the OS had been shared prior to the hearing and the judge said the final approved version would be sent to me when it was ready. (I’ve not yet received it.)

The hearing lasted just over an hour and this included breaks for counsel to read the draft order and consult with one another about minor amendments.

Part of the hearing involved what information Mr R’s ex-partner been given and the opportunity she’d had to respond.

The ex-partner’s (non) involvement in the case – notification and serving

When applying for a statutory will it’s important that people who might be affected by it (e.g. might have expectations as beneficiaries) are informed about the application.

At a previous directions hearing the judge had (as is pretty standard in these cases) ordered that the OS be invited to represent Mr R and also that the ex-partner be notified of the application.

The judge explained that he’d had some reservations (prior to being able to consult the OS) about going so far as to ‘direct full service’ on the ex-partner as this meant revealing extensive details of Mr R’s medical and financial situation to her.

However, the OS has subsequently gone on to accept the invitation to represent Mr R and, after discussion with the applicant’s counsel, the decision had been made to ‘serve’ rather than simply ‘notify’ her.

In retrospect, this seemed significant not least because the only response to the paperwork being delivered to the ex-partner’s house had been a message from her sister to Mr R’s son suggesting that only a covering letter had been delivered and saying “As this was so late in reaching us you can’t expect a response from [ex-partner] until she’s taken legal advice”.

Some time was spent clarifying the implications of this message. The photograph accompanying the text actually showed a set of paperwork beneath the cover letter which the solicitor charged with serving the paperwork had confirmed ‘accord in size to the paperwork I served’ – and the court also had the signed statement from this solicitor that he had served the paperwork.

The Judge concluded that it would be correct to say that the ex-partner had indeed been ‘served’ (rather than just notified) and he noted that the text message from the ex-partner’s sister simply gave ‘a reason for not responding’. He recorded the fact that there had been no response from the ex-partner (such as indicating that she opposed the application and giving her version of the facts and why she thought the statutory will was not in Mr R’s best interests).

Why authorising the statutory will is in Mr R’s best interests

The rest of the hearing was spent on the substance of why all parties in court (i.e. the applicants and the OS) believed that a statutory will was in Mr R’s best interests.

The OS supported removing the ex-partner as executor and replacing her with Mr R’s daughter (to become co-executor with Mr R’s son) because Mr R had (in early 2024) “when capacitous” given his son and daughter Lasting Power of Attorney (for property and affairs & for health and welfare) and his current expressed views now (even though incapacitous) were that he trusted his children.

The OS believed it was also in Mr R’s best interests to remove the statement referring to the ex-partner’s right of occupancy that was present in the 2014 will.

Mr R’s current wishes were “a factor of magnetic importance” – and as far as ‘past wishes’ were concerned the removal of the statement about his then-partner in the proposed statutory will could be consistent with Mr R’s wishes at that time too. The 2014 will stated that his children should inherit his house but that his then-partner, should have the right to live there unless she wanted to leave or got married to someone else. The OS’s position was that, arguably, the fact that she had already ended the relationship and moved out meant that, even under the terms of the 2014 will, her right to occupy had ended. But the problem was that these caveats in the will were directed to the period after Mr R’s death. It is not clear how the will applied if his then-partner had broken up with him and had moved out while he was alive. This option seems not to have been considered at the time, and the will was written in an ambiguous way that could leave the door open for potential litigation on this point.

The OS’s position was that the rights intended to be granted in the 2014 will were “conditional rights” founded on having a close relationship financially and emotionally – and this was no longer the case

The judge accepted this position, noting that the clause in the 2014 will was: “understandable in the context that he wanted to protect his partner”, but that:

“There was perhaps a gap in matters considered – it doesn’t address what happens if the relationship ends before Mr R’s own death. But if he HAD been asked about that it’s not much of a stretch to suggest it is very likely that he’d have thought her right to occupy should end.”

The OS’s position was that it was in Mr R’s best interests for the statutory will to reflect the significant change of circumstances (that the ex-partner was no longer in a relationship with Mr R, and the property was no longer her home) and made the point that removing any reference to right of occupancy for the ex-partner was practical, since she did not live there, and the house had actually been put on the market (and an offer accepted by his LPAs), and there were no tenancy rights under the housing act. The OS’s position was also that, if Mr R were able, he’d take into account the consequences of NOT making a statutory will – which would carry a (possibly small) risk of the ex-partner coming forward to make a claim, which leaves scope for expense and distress for his children in fighting the case.

The hearing concluded with some discussion of minor amendments to the order – but with the judge executing the order authorising the statutory will.

Reflections

This is a situation that could confront any of us – and our partners, ex-partners, family and friends.

Rights of occupancy are an interesting feature of wills that have come up in discussion with several of my friends – where, for example, their mother has died and their elderly father now has an (often younger) partner who has moved in with him. I suspect that a right of occupancy clause for the new partner or setting up a ‘life-time interest’ trust is a common feature in wills where an individual wants both to take care of his current partner and also to provide an inheritance for his children/grandchildren (by a previous marriage). Even when the (relatively new) relationship lasts until the death of the home-owner and they retain mental capacity to the end, the situation has its complexities – but I’d never thought about the implications of such a will after a break-up and how this is further complicated if the testator loses capacity (before or after the breakdown of the relationship). I suspect this gap in considering such implications is also common among people writing wills – and perhaps even some lawyers who help people draw up wills. (I would welcome correction on this last point.)

The case I watched highlights the importance of ensuring that wills are written very clearly and different changes of circumstances are considered.

This case also shows how quickly and efficiently the Court of Protection can act when needed.

Delays in bringing cases to court, or delays once they reach the court, are a common problem: many of the Open Justice Court of Protection Project blog posts highlight the glacial slowness with which cases can reach and progress through the courts.

Sometimes, of course, delay can be purposive and constructive – e.g., when it gives times for mediation. In this case, though, the unpredictable but imminent prospect of Mr’s R death meant the urgency was self-evident and there was no time for mediation. As the judge commented

“Many applications for statutory wills have due consideration over 3 to 4 months with the OS helpfully guiding applicants to a mutually agreed resolution but this one was urgent and I am grateful to the OS and the applicants working together on this.”

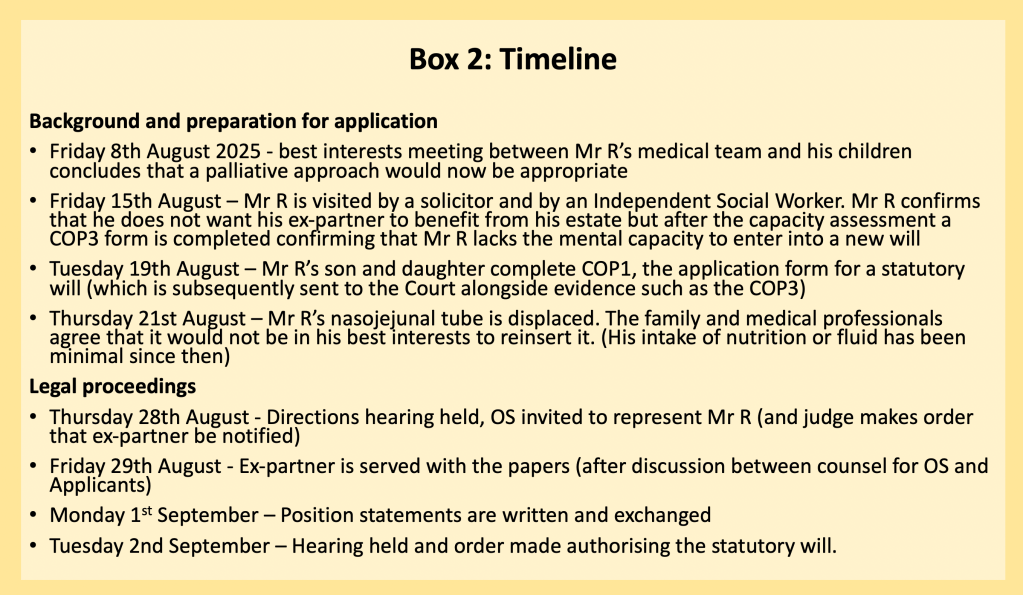

It is also clear that the urgency of the case increased even during the course of the application being made because Mr R’s feeding tube came out after his children had completed the CoP application form for a statutory will, but before the first directions hearing (see timeline in Box 2).

In this case, I think that (on the basis of the evidence available at the time) the Court has come to a timely and pragmatic solution that tried to consider and conform to Mr R’s wishes as much as possible. I hope that the hearing has helped to avoid the mess that could have been left if no statutory will had been approved. It is, however, unfortunate that court intervention for Mr R was needed, especially at such a difficult time for anyone who cared about him (or, indeed, had cared about him and shared a life with him in the past – however difficult the end of that relationship might have been).

I do not know the ex-partner’s views on the decision or what her expectations of Mr R were. I do think, though, that there is an argument for trying to ensure provision (for ourselves or others) during our lifetimes that cannot be withdrawn when a will is changed. It is not uncommon for someone who has been a main carer for many years and ‘promised’ certain benefits in a will to find those promises have not been realised in the final will and testament because the person who’s died simply changed their mind. But under those circumstances the potential legatee will have no grounds for challenging a will unless for example, they can prove undue influence or a failure to make ‘reasonable financial provision’ for certain types of dependents.

Anyone can change their will at any time when they have capacity to do so: that’s one of the reasons so many murder mysteries revolve around will making – and why wills can result in family conflict and expensive litigation.

Another lesson from this case is the need to keep wills under review. One option open to Mr R when he still had testamentary capacity may have been either to change, re-affirm or clarify his will after his partner ended their relationship.

It’s possible that Mr R might have had testamentary capacity in early 2024 after his partner had moved out (he apparently had the motivation and relevant mental capacity to appoint his children as his LPAs in that same year). It is also perhaps possible that he knew (or could have been informed by a clinician) that he might lose testamentary capacity in the near future. For me, then, this case is a reminder that carefully writing or rewriting a will should be one potential priority not just because we think we might die (which is inevitable) but because we might lose testamentary capacity – which, of course, a significant proportion of us are going to sometime before we die.

Jenny Kitzinger is co-director of the Coma & Disorders of Consciousness Research Centre and Emeritus Professor at Cardiff University. She has developed an online training course on law and ethics around PDoC and is on both X and BlueSky as @JennyKitzinger