By Celia Kitzinger, 16th October 2025

More than three years ago, back in July 2022, a 42-year-old man diagnosed with schizophrenia, Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome and Autism Spectrum Disorder was a voluntary patient in hospital, following an admission under s.3 Mental Health Act.

The defendants, publicly named as Jim and Tess Slocombe[1], took him home contrary to medical advice – and ever since then the public authorities have tried and failed to gain access to him. P is entitled to free after-care services under s.117(2) of the Mental Health Act but the relevant professionals have been prevented from meeting him to assess whether or not he needs after-care, and if so what kind of care would be appropriate.

According to Francesca Gardner, counsel on behalf of P by his litigation friend the Official Solicitor: “All (extensive) efforts to meet with [P] to assess his eligible care and support needs have been unsuccessful; this is an assessment that he is entitled to, and it has not been possible to consult him about it. All of those efforts (without exception) are alleged to have been thwarted, frustrated and obstructed by [the defendants]. [P’s] legal representatives have not had the opportunity to meet with or speak to [P] in order to ascertain his views. P is an adult, these proceedings are about him and he is entitled to speak with his legal advisers”.

The proceedings began on 13th July 2023 under the inherent jurisdiction, seeking access to P for the purposes of ascertaining his wishes and feelings about after-care. There were various adjournments due to Mrs Slocombe becoming ill, the non-availability of a sign-supported English interpreter, and the non-receipt of the expert capacity report. On 28th March 2024, HHJ Burrows recorded that P lacked capacity in all the domains assessed and consented to his assessment under the Care Act 2014 and for after-care under the Mental Health Act 1983. The assessments were ordered to take place by 21 May 2024. The Court of Appeal refused an application from Mr and Mrs Slocombe to appeal this order.

Following further delays, the public bodies made a “without notice” application for P to be conveyed to hospital for assessment of his mental health after-care needs. The judge rejected the application but made orders with a penal notice attached requiring Mr and Mrs Slocombe not to interfere with assessments. Their appeal against these orders (heard by Mrs Justice Theis) was found to be “totally without merit”.

The defendants are now alleged to have breached these orders by not permitting professionals to assess P – by preventing him from attending an appointment, and by refusing professionals access to P in the home. They stated in writing that they intended to refuse access and to “contravene the order”.

The public bodies (Cheshire West and Cheshire Council, and Cheshire and Merseyside Integrated Care Board) made an application for committal. They are represented by Vikram Sachdeva KC. The defendants are litigants in person (although they are entitled to non-means-tested legal aid).

Committal hearing

The hearing I attended on 6th and 7th October 2025 (COP 14240025) before His Honour Judge Burrows was intended to be a two-day committal hearing[2]. As it turned out, the committal hearing did not take place because the two defendants left the courtroom – which they’d attended in person – following an accident. I didn’t witness this, but when I was admitted to the court (via a remote link) almost an hour after the hearing was due to start, the judge said: “Mr Slocombe is tending to his wife who has suffered a fall and an ambulance has been called. We will resume in 2 hours.” This was followed by some discussion about whether the committal proceedings, when they resumed, might be only against Mr Slocombe, on the grounds that “clearly Mrs Slocombe is in physical as well as mental distress and there’s going to have to be some re-evaluation of her ability to participate this afternoon” (judge)[3].

However, when I returned to the courtroom at 2pm, it transpired that both defendants had “driven off”, having apparently cancelled the ambulance. They did not appear to have communicated their intentions to the court, and nobody knew where they were.

This is the second committal hearing in this case that I’ve tried to observe. At the last one, on 30th July 2025, the defendants did not turn up at all. I understand that they wanted the hearing to be adjourned on medical grounds – and also that they were asking for reasonable adjustments to support their involvement in proceedings, given their own disabilities (for which the judge stated they have not provided medical evidence). Neither defendant is legally represented because (they say) “we dislike the idea of needing to involve more lawyers in P’s confidential information and increasing the number of people we have to communicate with – verbally or written” (quoted from the position statement of counsel for the public bodies). The defendants clearly feel victimised: they have accused two solicitors for the local authority of bullying them and threatened to report one to her professional body.

At that last occasion, in July 2025, the judge said that “the person at the very centre of this case, P, has become completely obscured by the litigation process. On every occasion I’ve had the opportunity to do so, I’ve said this case is about him, and he’s the only person I’m concerned about. I am amazed that [the defendants] are behaving in ways that compromise his welfare. I want him to have access to his rights under s.117 of the Mental Health Act. The aim of these proceedings has been to secure orders that ensure he receives what he’s entitled to”.

Two months later, it seems we were no further along.

Various ways forward were then suggested to the court.

It’s possible to proceed with a committal in the absence of the alleged contemnor if certain conditions are met: the case of Dahlia Griffith, sentenced to 12-months imprisonment in her absence, was mentioned (Re Dahlia Griffith [2020] EWCOP 46) and when I checked out the judgment in that case I found a useful discussion of the legal principles on whether the court can proceed without a defendant, in an earlier case from the Family Division (Sanchez v Oboz [2015] EWHC 235 (Fam)).

Alternatively, under Court of Protection Rules 21.7(2), the judge could issue a bench warrant. This would mean that Mr and Mrs Slocombe (or perhaps, given his wife’s injury, just Mr Slocombe) would be arrested and brought to court for the second day of the committal hearing. Drawing attention to the considerable cost implications to not pursuing the hearing, as planned, Vikram Sachdeva KC promoted this option on behalf of the public bodies, and said that the public bodies intended to seek costs against the defendants for their “unreasonable” behaviour.

The judge was reluctant to pursue either course of action at present on the grounds that “the wife is unwell and the husband is essentially her carer”. He said “my preliminary view is that I am reluctant to issue a bench warrant against relatively elderly [people] who have if I can put it this way, their problems – when there may be other measures that can be put in place”.

The court adjourned for 20 minutes to give counsel an opportunity to consider what these other measures might be, and to consult their clients and take instruction.

On resuming the hearing, counsel for the public bodies raised their concern about the defendants’ “serial non-compliance with orders, which is seriously prejudicing P’s best interests. P has not been able to have a s.117 assessment of his needs for 3 years because of [the defendants] blocking of access to him”. Vikram Sachdeva KC did not pursue either continuing the hearing without the defendants, nor the bench warrant, but asked for the committal hearing to be relisted at the earliest opportunity.

It had taken some time to find a physical courtroom where this hearing could take place. Committal hearings are supposed be in person, and there is always the possibility of someone needing to be transferred to prison directly from the court (as happened recently in the case of Luba Macpherson). Addressing me directly, the judge said “There’s a dock at the back of this room – but you can’t see it because of the way the camera is positioned. There aren’t 2 burly police officers in the room at the moment, but if it came to the point where I was considering sending someone to prison there would be. The courts I generally sit in are not in criminal courts – this is a criminal courtroom – and finding available courts is a problem at the moment. That’s why it’s taken so incredibly long to list this hearing“.

The matter of listing the next contempt hearing also arose the following day, and counsel for the public bodies indicated that they would not in fact be asking for a prison sentence since there was “no point” (something I’ve heard both counsel and judges say in other contempt cases too) – the implication being that perhaps a secure courtroom wasn’t needed. Counsel was firmly corrected by the judge, who referred to the Court of Appeal case, B (a child) (Sentencing in contempt proceedings) [2025] EWCA Civ 1048 – a case whose effect on Family proceedings I’ve already blogged about (“Sentencing in contempt proceedings: Punishment and coercion in a case before Lieven J”). “It’s about the court’s authority”, the judge said “this court lives and dies by its declarations”.

The next committal hearing will be listed to take place in person in the same (criminal) courtroom on 3rd and 4th December 2025.

Closed (‘ex parte’) hearing

I was unsurprised by what happened next. The judge announced that he would now preside over a private ‘ex parte’ hearing, and I assumed I would be told to leave at this point. I was very pleased that the judge allowed me to stay and observe it (and nobody present objected). When a hearing takes place without notice to one of the parties (it’s almost always family members) it seems to me very important that someone independent should be there to witness it, even though publication of anything about the hearing is embargoed (or occasionally banned altogether). In this case, the judge lifted the embargo after the purpose of the hearing had been achieved, at the end of the following day.

There was a ceremonial shift from the public committal hearing to the private ex parte hearing: first the judge and then counsel removed their wigs to symbolise the change of status.

It quickly became apparent that (as I’d already guessed) the private hearing was about how to remove P from the care of the defendants and take him somewhere for assessment. My expectation that this would be so was based on the Official Solicitor’s position statement, where she said: “Matters cannot continue in this way. Irrespective of the court’s determination of the committal application, the Official Solicitor invites the court to case manage the substantive application before the court, at the conclusion of the committal hearing. The applicants are invited to set out, in short order, what is proposed in terms of next steps in order to secure an assessment of [P].”

Counsel for the public bodies announced, without further ado, that an application had already been made under s. 135 of the Mental Health Act and would be heard by a magistrate the next morning. If successful, this would result in a warrant that would authorise the police, an approved mental health professional (AMHP), and a registered medical practitioner to gain entry to the premises where P is residing (by force if necessary) in order for an assessment to take place there, and for removal, if that is seen fit, to a place of safety. Vikram Sachdeva KC added (perhaps for my benefit): “This is not us being heavy-handed. We’ve been besides ourselves with simply trying to assess him. I’ve been tearing out whatever’s left of my hair. After assessment we might say to [the defendants] ‘he can continue to live with you if we can check on him and if you give him all his medications – they haven’t been doing that’. We made an application to remove him a year ago, in July 2024, but the Official Solicitor’s position was then that it was in P’s best interests to go for a contempt hearing instead and Your Honour agreed that the risk to P’s health and welfare arising from forced removal at that stage was too great. It was hoped that, threatened with prison, [the defendants] would snap into line. But oh no, not [these defendants]. So here we are today.”

In case the s.135 application were to fail, the applicants wanted an order from the Court of Protection as well, to permit P’s removal to a psychiatric ward. But the details of that could be worked out the next day (also in private and without notice to Mr and Mrs Slocombe) if necessary. They thought they would know the outcome of the application by 10am on 7th October 2025, so the hearing would resume at 12 noon (or be vacated if it wasn’t needed).

The hearing resumed at almost 12.30 the next day. I assumed this meant the s.135 application under the Mental Health Act had been refused and that the applicants now wanted the judge to approve removal under the Mental Capacity Act instead. But it turned out that actually the application had been approved, but was not yet executed. The plan was for the police and other personnel to go to the defendants’ house at 2pm that day, and if they’re not there to go to their caravan (and there was apparently a third possible location they might be at as well). Where ever they are, P will be with them.

The judge asked whether he was being asked to do anything in the meantime. Only to authorise a third-party disclosure order against the Ambulance Service (said counsel for the public bodies) to determine the circumstances under which the ambulance called to the court for Mrs Slocombe the previous day had been dismissed. (This may be relevant to the costs application the public bodies are seeking.)

The parties then discussed with the judge what exactly the legal situation would be if the s.135 order was not executed because P and the defendants could not be located, or alternatively if it was executed and – on assessment – P was found not to be detainable under the Mental Health Act.

It was, as the Official Solicitor said, “not a foregone conclusion” that P would be located – not least because it seems that the defendants have a video doorbell at their home that can be accessed by mobile phone, so if they’re away from home, they may become aware of professionals visiting their house in connection with the s.135 order and take evasive action.

Even if P is located, the justification for detention under the Mental Health Act is to avoid harm to the patient or to others. This is not at all the same as detention for the purposes of a s.117 assessment of needs. So it’s quite possible that P might be sufficiently well not to be detainable – and the action already taken under s.135 would have alerted the defendants to (some of) the authority’s concerns. This was a very real fear in court.

“An unsuccessful attempt to remove P could have catastrophic consequences”, said Francesca Gardner for the Official Solicitor. “The fear is that P could be hidden, or taken away”, said the judge. Vikram Sachdeva KC reminded the judge of “various things said by [the defendants] that cause us grave concerns, like “if you come and try to get him, he won’t be there” and they also said something about his being ‘better off dead than being in the hospital’”. The judge confirmed that these remarks were made “in a hearing before this last application”. (I recalled that there have been other recent cases when attempts to assess P were followed by abduction e.g. Re AB & Ors [2025] EWCOP 27 (T3)[4]). There was also a possibility that P could be found, taken to a psychiatric hospital for assessment, but then released. This would be (from the court’s point of view) a disastrous outcome.

It was a tense wait to hear whether or not P had been found, and if so, whether or not he had been taken to be assessed, and if so whether or not he had been found to be detainable.

Meanwhile the parties, and the judge, were exploring different ways of moving forward with reference to case law which unfortunately I’m unfamiliar with and haven’t been able to locate on the basis of the references made to it in court (which I’ve written down as follows: “Charles pulled back in JG South London…”; “the JS case by the Vice President…”). (Update: the JS case is Manchester University Hospital NHS Foundation Trust [2023] EWCOP 33 – and it cites the Charles J case: J in GJ v The Foundation Trust & Anor [2009] EWHC 2972 (Fam))

Eventually, the judge asked: “Are you asking me to make a declaration that it’s in P’s best interests to be assessed under s.117 MCA and under the Care Act and also that he can be taken to a place in order for that assessment to be carried out and detained there for so long as it is necessary for that assessment to take place? That would achieve the objective of these proceedings.”

“It looks like I am”, said Vikram Sachdeva KC, having ‘turned his back’ on the judge to look at his clients, seated behind him. “They’re both nodding vigorously”.

So, it seemed that the judge was considering making an immediate order (conditional on P not being detained under the MHA) to detain P under the MCA in a psychiatric hospital for assessment.

Concerns were immediately raised by the Official Solicitor: “It’s difficult to positively agree with a proposal that goes against the assessments and conclusions of those on the ground tasked with this” It’s also, she said, “difficult to see how the least restrictive option can be on a psychiatric ward”.

Judge (to VS): If the AMHP [Approved Mental Health Professional] executes the warrant and decides not to convey him to hospital for assessment, why should I convey him to hospital for assessment?

VS: No. It would be for a different assessment. A s.117 assessment.

Vikram Sachdeva KC read out the wording of s. 135 of the Mental Health Act to highlight its implications for this case.

The warrant had been issued by the magistrate, he said because: “… there is reasonable cause to suspect that a person believed to be suffering from mental disorder (a) has been, or is being, ill-treated, neglected or kept otherwise than under proper control, in any place within the jurisdiction of the justice….” (the key word there being “neglected”).

That warrants permits “any constable to enter, if need be by force, any premises specified in the warrant in which that person is believed to be, and, if thought fit, to remove him to a place of safety with a view to the making of an application in respect of him under Part II of this Act, or of other arrangements for his treatment or care”.

The “if thought fit” part involves the Approved Mental Health Professional in making decisions, including whether or not the person needs to be removed from the premises; if they decide that they do, then once the person is in “a place of safety”, another application needs to be made as to whether or not to detain them there.

The sense of urgency in the courtroom about what would happen next meant that things then became quite heated.

VS: You are not in any way second-guessing what the AMHP will do because the AMHP is exercising a different jurisdication and asking different questions.

Judge: So, an AMHP may decide he should go to hospital – and if he gets there and the doctor says he’s not detainable, then are you saying he ought to be kept there for s117 and Care Act assessment?

FG: (cutting across this discussion): I’m acutely aware of time, and that any moment we might-

VS: If the warrant is executed, they get their foot in the door. At that point either the AMHP decides P is not going anywhere and that no reasonable doctor would detain him. Or he may decide that, yes, he ought to be taken to place of safety, where he will be assessed for s. 2 or s.3 detention. If he’s then assessed and the psychiatrist says “no” to detention, then that’s the end of it, for the MHA.

FG: You’re being invited to make an anticipatory order that in the event that an AMHP enters the property and takes the view that they do not consider it fit to remove P to a place of safety (she looks at watch), then you are invited to make an order to remove him to hospital, with restraint. We oppose the application to convey P in these circumstances, where there is very limited information available about him, and a mental health professional considers it “not fit” to remove him to a place of safety.

Judge: You’re really saying that the AMHP on the ground is better placed to make the decision that I am.

FG: It goes further than that. It’s not beyond the bounds of possibility that the AMHP may say that removing this person by force to a place of safety is going to do more harm than good. But your order would override that. And a sense of realism would say this is not a short-term order. The likelihood of P being discharged home in the next few days in slim.

Judge: So, practically, the local authority’s position is that these proceedings have been going on for over 2 years. They have a very modest ambition in the scheme of things: to assess him for s.117 and Care Act needs. Even that modest ambition has been frustrated by [the defendants]. Here we are today potentially with our foot in the door, with sight of P for the first time, and it’s being said that it would be disproportionate to convey him to, or having conveyed him to, to hold him, in a place for a s117/Care Act assessment?

FG: No, the concern is that as we speak-

Judge: (interrupts) You oppose it because it’s too early – but would it not be too early at 3 o’clock if we get the information that he’s gone to hospital. You’re saying it’s too early because I need more information. Are you saying tomorrow or the next day? By which time it may be too late for the best interests of your client.

FG: We would need to know the reasons why an AMHP would say it is not fit to remove him.

[…]

VS: We have evidence that P’s mental health has deteriorated. We have got the bed today. The Official Solicitor asks why removal to acute psychiatric hospital (and not to a less restrictive option) is in his best interests. And the answer to that it’s the only available option. They’re all too worried about his mental health status to take him anywhere else – it’s not an available option. We were advised it wouldn’t be safe. That’s the short answer. With the greatest respect to the Official Solicitor, we’ve been put off for a year because of the Official Solicitor’s great idea of getting [the defendants] to comply with the orders – which they have not.

Judge: That balance has shifted because of time moving on. First, do I have to make an order now, because it would be an anticipatory order.

VS: Yes. Because they could leave again and then it would be too late.

Judge: Yes, and then we’d have to get the foot in the door again and it’s taken two years so far. So that’s your answer to that. But if I make a permissive not mandatory order, who would make that decision based on circumstances on the ground.

VS: The social work department of the local authority – they would refer it to the senior social worker. […] But, stepping back, the idea that it’s not in P’s best interest to be assessed for his s.117 needs-

Judge: (interrups) Nobody is arguing that assessment is not in his best interests. The issue is whether it’s necessary and proportionate to use force and convey him to an acute psychiatric hospital.

VS: That’s not so different from the argument that was made last August – that this would be a significant intervention for P, and that’s why Your Honour decided to go through the contempt process in the hope P could stay at home. That hasn’t worked. P was pre-diabetic when we last assessed him 4 years ago. He’s put on 4 stone since then. His needs might be physical health needs as well as mental health needs-

FG: (interrupts – receiving news on her mobile phone) He wasn’t at the house! They are going to the caravan.

The judge called an adjournment.

Removal of P

Around 45 minutes later the hearing resumed. Vikram Sachdeva KC reported back. “They went to the house – he wasn’t there. They went to the caravan and there were two cars outside. The police effected entry and removed P. He was sufficiently unwell that they were very concerned about him. He was aggressive and they had to handcuff him. [Mr Slocombe] was, uhm, not pleased to have them visit and followed behind in his car. He was conveyed to hospital under s. 135, and detained there under s. 2 and taken to the Psychiatric Intensive Care Unit. In the nick of time, Your Honour”.

Arrangements for the committal were confirmed. Francesca Gardner was invited to raise any remaining concerns and said she had nothing to add. “It’s a relief in one way that the Mental Health Act was successful in achieving the outcome that the applicants want. And that the concerns about P were not misplaced”.

As it turned out, the substantive matter of the case has now been dealt with under the Mental Health Act and not by HHJ Burrows in the Court of Protection. It was fascinating to watch how this happened, and to be able to ‘eavesdrop’ on the practical and legal dilemmas created by this situation as it unfolded in real time. In published judgments (when there are published judgments, which is in itself rare!), it’s hard to appreciate how decisions emerge in response to changing events on the ground, and how competing arguments are advanced (often fervently) by people committed to P’s best interests but with different perspectives on how P’s best interests should be served – especially, in this case, in the absence of much information about him. I found myself resonating to all the arguments of the parties at different times: I could see disaster both in the prospect of removing a happy and healthy P from his home by force, and in risking the abduction or death of a seriously unwell P. For me, this was an intense immersion in the decision-making issues confronting the court.

The judge confirmed that, now that the purpose for which the hearing had been convened (the removal of P) had been accomplished, I could report on the case[5]. And he ended the hearing by referring to the closed proceedings in the case before HHJ Moir (subsequently made public by Poole J and heavily criticised by members of the Open Justice Court of Protection Project[6]) – saying that “the existence of a private hearing on top of a public one, means that proper reporting is sometimes compromised with duplicity”. Thank you to HHJ Burrows, and to the represented parties, for ensuring transparency in this challenging case and for (unusually) permitting public attendance at a closed hearing.

Celia Kitzinger is co-director of the Open Justice Court of Protection Project. She has observed more than 600 hearings since May 2020 and written more than 100 blog posts. She is on LinkedIn (here), and also on X (@KitzingerCelia) and Bluesky @kitzingercelia.bsky.social)

[1] The transparency order permits me to name the defendants but not P. I am also not allowed to specify the nature of the relationship (if any) between the defendants and P. I understand that the decision to release the names of the defendants was made in accordance with Rule 21.7 of the 2017 rules as amended this year to require the court to consider, before the first hearing of any contempt proceedings, whether to make an order under rule 21.8(5) for the non-disclosure of the identity of the defendant in the court list. This is to prevent the utility of any subsequent non-disclosure order being undermined by the prior public notice of the identity of the defendant.

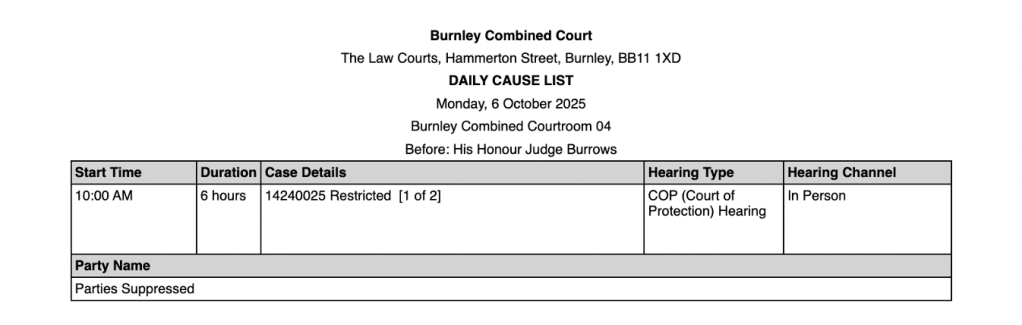

[2] It was incorrectly listed by HMCTS, contrary to the explicit instructions of the judge (as he explained to me when I raised the matter). I have since complained to HMCTS, noting that this is a frequent problem with committals. Here’s how it was listed – without any indication at all that it was a committal to prison, and entirely without reference to the Practice Guidance on how committals should be listed. This hearing was also not included in the COP lists (only in the daily cause list for Burnley). This is a complete failure of transparency. (It was subsequently – briefly – correctly listed, including the defendants’ names, for the following day, but seems then to have been removed from the list altogether, presumably because the hearing on 7th October 2025 was ‘without notice’ to the defendants.)

[3] We are not permitted to audio-record court proceedings. The text that purports to quote what was said in court is based on contemporaneous touch-typed notes and is as accurate as I could make it – but is unlikely to be verbatim.

[4] We blogged about the case most recently here: “Two years on, P is still missing”, with an earlier post here: “Removing P to another country to evade the orders of the court”

[5] I subsequently emailed Vikram Sachdeva KC asking to be told once the defendants had been informed about it, since it would be obviously inappropriate for them to learn the details of this hearing from a blog post and not from the court.

[6] This is a long running case, with several published judgments and blog posts. I reflected on the transparency implications of holding closed hearings in parallel with public hearings in this blog post (which links to relevant judgments and earlier posts): Reflections on open justice and transparency in the light of Re A (Covert Medication: Closed Proceedings) [2022] EWCOP 44