By Celia Kitzinger, 5th November 2025

Last time I wrote about this case, a few months ago in July 2025[i], the 90-year-old protected party (P), who has dementia, was in a nursing home, and deeply unhappy. She was refusing to eat or drink very much, declining to take her medications, and saying she wanted to die. She had lost two stone in weight over a two-month period and was seriously malnourished. There was a suggestion that as her physical condition worsened, hospital treatment might become clinically indicated, including possibly provision of clinically assisted nutrition and hydration.

I was interested in this case because P had an Advance Decision to Refuse Treatment (ADRT) made a couple of years earlier, refusing any treatment that required her to go into hospital “even if my life may be at risk from this refusal”.

In fact, she had already been admitted to hospital earlier in the year (the Health Board said they didn’t know about her ADRT at the time) and had been extremely unhappy there. Subsequently (after a failed return home), she’d been discharged from hospital to the nursing home – and as I reported in my last post, this was done unlawfully, without the knowledge of the court. She’s been in the nursing home ever since.

Alongside the s.21A Deprivation of Liberty proceedings (relating to P’s capacity to decide for herself and the least restrictive options for her care and residence), the Health Board and the Local Authority are concerned about whether, and if so how, the ADRT would “interfere” with the provision of medical treatment for P, especially as some treatments would require a return to hospital.

I’ve watched two more hearings in this case since the first one I stumbled across on 21st July 2025: one on 21st August 2025 and then, the most recent, on 3rd November 2025. At this most recent hearing the judge, District Judge Keller, found P’s ADRT to be invalid. He ruled that “there should be appropriate documentation placed on her medical records to show that it must not be relied on”. Another hearing is listed for February 2026 to deal with remaining issues relating to deprivation of liberty.

On the basis of the (limited) information I have about the case, it seems to me that the judge was entitled to make the decision that P’s ADRT was invalid. That causes me concern because of what it means not just for P but for everyone else with ADRTs. Do our ADRTs adequately reflect what we want? Do we really understand what they might mean for how we are treated – or not treated – in the future? And if we do understand them and mean them to be respected (even in the face of subsequent non-capacitous behaviour that flies in the face of the decisions we have made), is there anything we can do about that?

This ADRT in this case was made with the support of a well-respected charity, the Paul Sartori Foundation, with specialist expertise in advance care planning[ii]. The charity runs training courses for professionals[iii] and publishes a plethora of documentation, both for professionals and for members of the public – including this EasyRead guide[iv] (which looks very good to me).

As I understand the process, someone described as a “Macmillan nurse” working for the Paul Sartori charity, visited P at her home following a referral (I think from her GP surgery), and talked through her medical decisions with her before drafting the document for her to sign.

It must surely have been the intention of the charity to create for P a valid and applicable ADRT that accurately reflected her wishes and decisions at the time, and would result in the decisions she had made to refuse hospital treatment being respected if or when she lost capacity to make her own decisions in the future.

But the finding of the court was that in fact the document she signed did not reflect her wishes at the time – and that it likely had procedural defects in any event; and that it should not now be followed by the people involved in her care – not as a binding document and not even as an indication of her wishes and feelings.

This judgment has serious implications for all of us who want to refuse medical treatments in the event of possible future loss of capacity. It also has implications for the charities that support people to make these documents.

I’ll start by summarising the relevant “Legal background” to the case. Then I’ll describe the three hearings I observed (“Hearings”)[v]: the oral judgment is reported in my account of the November hearing[vi]. Finally, in “Reflections”, I consider what this case means from my personal perspective as an older person with an ADRT of my own and for the charities and other individuals and organisations who promote ADRTs for others.

1. Legal background

Advance Decisions to refuse treatment (ADRTs) are a way of planning ahead for future loss of capacity. If you know, now, when you have capacity to make decisions about medical treatment, that there are certain treatments you would want to refuse under specific conditions (e.g. you might know that you want to refuse clinically assisted nutrition and hydration if you were in a prolonged disorder of consciousness), you can make an ADRT which, if valid and applicable, has the same legally binding effect as if you were making a contemporaneous capacitous decision: it would be unlawful for doctors to provide you with the treatment you have refused.

The Mental Capacity Act 2005 (ss. 24-26) sets out the statutory rules relevant to the creation, validity, applicability and effect of ADRTs , and it’s fleshed out by a small body of case law.[vii] On the face of it, they’re not complicated documents. In order to refuse life-sustaining treatment, your refusal must be in writing and accompanied by a statement that it’s to apply even if your life is at risk. It must be signed it in the presence of a witness who signs it to acknowledge your signature. You don’t need a solicitor to make them or a doctor to sign them off, and they can be written in ordinary lay language.

When they reach court, it’s generally because of doubts about their validity or applicability (or most recently their authenticity). For example:

- No witness to P’s signature. This is a fatal flaw. Judges have decided, based on the statutory requirements in the Mental Capacity Act 2005, that without a witness to P’s signature a (purported) ADRT cannot be relied on – though it can still be treated as an expression of the person’s wishes and feelings (Barnsley Hospital NHSFT v MSP [2020] EWCOP 26; Re D [2012] COPLR 493)

- Concern about P’s capacity at the time the ADRT was signed[viii]. This relies on a retrospective assessment of capacity (sometimes aided by capacity assessments made at the time). In some cases, judges have found that the person did have capacity at the time the ADRT was signed (e.g. (NHS Surrey Heartlands ICB v JH [2023] EWCOP 2). In other cases, they’ve decided that the person did not have the requisite mental capacity at that time (e.g Re QQ [2016] EWCOP 22; A Local Authority v E [2012] EWHC 1639).

- Fraud or undue influence: There may be concerns that the ADRT is a fraudulent document (e.g. that P’s signature has been faked) or that it was created under coercion or undue influence. That question arose, but was not determined (because the party making the allegations decided not to pursue them), in the case of Re AB (Validity and Applicability) [2025] EWCOP 20 (T3). We blogged about the “authenticity” issue here: Authenticity of a “Living Will”.

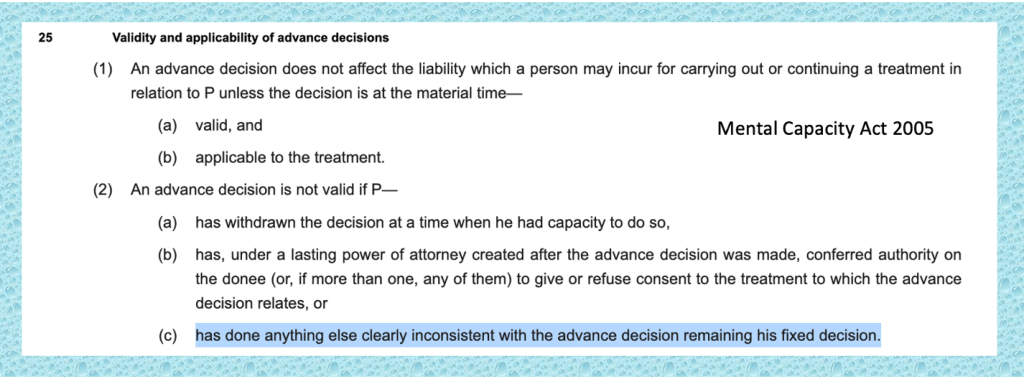

- Behaviour (after loss of capacity) inconsistent with the ADRT remaining P’s fixed decision. The Mental Capacity Act 2005 provides that the person who made it can subsequently withdraw it (s.25(2)(a)) or displace it by a Lasting Power of Attorney that grants the donee the right to make the treatment decisions specified in the ADRT (s.25(2)(b)). Obviously, this can only be done when the person has the mental capacity to effect the withdrawal or to appoint the Attorney. The question of what else a person can do that would have the effect of invalidating the ADRT was decided in a case before Mr Justice Poole who held that s.25(5)(c) means that a person might behave in ways “clearly inconsistent” with the ADRT, either before or (crucially) after loss of capacity to make the relevant decision – e.g. by sometimes saying (as in the case before him) that she would be willing to have a blood transfusion, which the treatment refused in her otherwise valid and applicable ADRT) (Re PW (Jehovah’s Witness: Validity of Advance Decision) [2021] EWCOP 52).

By contrast, minor procedural defects are not necessarily treated as invalidating an otherwise properly prepared ADRT. Judges have ruled that ADRTs are valid and applicable despite:

- confusion with dates of signature (NHS Surrey Heartlands ICB v JH [2023] EWCOP 2) including one case in which the date of signature was entered as the date on which the ADRT was to expire (The X Primary Care Trust v XB [2012] EWHC 1390).

- absence of an explicit statement that P had signed it in the presence of the witness (who had also signed it) (Nottinghamshire Healthcare NHS Trust v J [2014] EWHC 1136)

2. Hearings

Following the application (dated 12th June 2025) from the Health Board asking the court to make a decision as to the validity and/or interpretation of the ADRT, there were hearings on 11th July, 21st July, 22nd August and 3rd November – of which I observed all but the first. All the hearings were before DJ Keller[ix] sitting remotely as a nominated judge of the Court of Protection at Port Talbot Justice Centre. At the three hearings I observed, the parties and their representatives were as follows:

- Counsel for the applicant Health Board (Hywel Dda UHB) was Jack Anderson at the July hearing, Laura Shepherd at the August hearing, and Rachel Anthony, Deputy Head of Legal Services at Hywel Dda UHB at the November hearing

- Counsel for the Local Authority, Pembrokeshire County Council (who replaced the Health Board as applicant after the July hearing), was Melissa Jones at the July hearing, and Rachel Harrington at the August and November hearings.

- Counsel for the protected party, P, instructed via her litigation friend (I think a mental capacity advocate of some kind – and definitely not the Official Solicitor) was Jordan Briggs of Doughty Street Chambers (instructed by CJCH) at all three hearings.

- The daughter of the protected party was joined as a party (third respondent) for the August and November hearings. She did not have legal representation and chose not to attend the November hearing.

The focus of my report is on the specific issue of the ADRT but this wasn’t the only issue before the court, which also addressed issues relating to deprivation of liberty and how to try to reduce P’s unhappiness and distress in the nursing home.

2.1 The July hearing

The hearing on 21st July 2025 addressed quite a wide range of matters including P’s unlawful detention and possible breach of an ADRT, plus P’s health issues. It opened with a run through the chronology of what had happened so far.

On 10th August 2023, P signed a document which read (in part) as follows:

“There is no way I want to go into hospital again and therefore refuse treatment that would require me to go into hospital, even if my life may be at risk from this refusal. I will accept treatment aimed at preserving my dignity and keeping me pain free and comfortable including antibiotics for symptom relief, but only if they can be administered at home. If medical assistance is called it will be for advice or treatment that can be administered at home to ensure my comfort, it will not be for transferring me to hospital.”

“I am 88 years of age and I will take my chances. No way do I want to go into hospital; in my home is where I am staying.”

In March 2025, she was admitted to hospital with abdominal pain. The Health Board says they didn’t know about her ADRT at the point of admission.

In hospital, P refused to engage with occupational therapy and physio, declined most of her medication, ate and drank very little, and “presented with challenging behaviour”. She was found to have capacity to make her own decision about care and residence and discharged home nearly a month later with a domiciliary care package.

On the evening of her discharge, in early April 2025, a carer attended, found her unable to mobilise and telephoned emergency services. An ambulance came to the house. P was abusive and agitated and refusing observations and was assessed as lacking capacity (although capacity for what, exactly, was not specified). Her daughter persuaded her to be re-admitted to the hospital.

Hywel Dda UHB learnt about the existence of P’s ADRT in early June. A little more than a week later, they applied to the Court for decisions as to how to interpret P’s ADRT, and for a s.21A decision – although they then discharged her to a nursing home without the approval of the court at a meeting at which P herself was not represented. The minutes of the meeting were not sent to P’s RPR. The discharge occurred without completion of the Quality Assurance Process and commissioning documentation, or funding being agreed, and Long Term Care were not informed about the discharge date.

Turning to the current situation, counsel for P reported that P’s weight continued to fall (her BMI was 15.1) but she was “slightly brighter” recently following a change in room to one with natural light from a window behind her bed. She continued to have “a patchy approach to both eating and personal care”. She was being “supported and encouraged” to eat and drink.

Counsel for the Health Board pointed out that “if there was any question of more interventionist feeding methods, that would require very careful consideration of her best interests” because methods of clinically assisted nutrition and hydration can be “intrusive and distressing if someone is not compliant with them”.

There was an agreed order before the court that before the next hearing, listed for 21st August 2025, the Local Authority would serve a statement giving an update on P’s presentation and well-being, assessments of her mental capacity to make decisions about care and treatment, a multi-disciplinary needs assessment, evidence relating to her eating and drinking, acceptance of personal care and medication, and any objections she makes to her confinement: they were also asked to list steps that could be taken to improve P’s welfare, and alternative options for residence and care. The daughter was given permission to serve a statement about her discussions with her mother about Do Not Attempt Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation (DNACPR) and about the ADRT and a number of other matters. The RPR would serve a statement setting out P’s current wishes and feelings, including her view on the meaning of the ADRT. All these matters would be discussed at a Round Table Meeting the week before the next hearing.

The principal purpose of the next hearing would be to make a decision as to the interpretation of the ADRT. The court would also issue further directions relating to deprivation of liberty. The hearing was listed for 3 hours.

There was a brief exchange about what might happen if P’s disinclination to eat and resultant weight loss caused concern to the extent that a nasogastric tube, or PEG tube, was considered medically necessary before the case came back before DJ Keller. I think I understood that an urgent application to a Tier 3 judge in the Royal Courts of Justice would need to be made.

2.2 The August hearing

The plan was that the judge would be in a position to make a decision about the validity and applicability of P’s ADRT at this hearing on 21st August 2025, but that didn’t work out. It seems that the parties had applied to adjourn the hearing, but the judge went ahead with it anyway: it took less than an hour.

The most significant aspect of this hearing was the information that had been conveyed by the daughter at the Round Table Meeting the previous week. The account she had provided was described as “striking”. She also spoke to the judge in court, relaying her version of how events had unfolded.

The Local Authority reported that P’s daughter had “provided information about the circumstances in which the advanced decision came to be made, with the involvement of a nurse from the Paul Sartori Foundation (hospice at home). She also indicated that the apparent witness was not present when the advanced decision was signed but signed later”. The parties had agreed, in the light of what the daughter had told them, that “further information is needed from the Paul Sartori Foundation and, if possible, from the witness before the court can fairly determine the meaning of the advanced decision. It is proposed that a third party order be made for the records of the Paul Sartori Foundation. [P’s] litigation friend has offered to attempt contact with the witness”.[x]

According to the Health Board, P’s daughter had reported not only that the neighbour who was said to have witnessed the signature on the ADRT did not actually do so, but also that P wouldn’t have been thinking about treatment options in a care home and transfer to hospital for issues relating to eating (which are the decisions to which the relevance of the ADRT is currently under consideration). Rather “the focus of the decision was in relation to the treatment for bowel problems she was anticipating undergoing at that time”. The daughter said that her mother “would not have properly understood the effect of the decision, and did it because she wanted the PSF people to leave the house and thought that signing would be the quickest way to achieve this aim”.

There was also a report of what the daughter had said at this Round Table Meeting from counsel for P:

a. The advance decision arose after [P] was discharged from hospital following investigations into her bowel.

b. Without [P’s daughter] knowing how this came about, an individual from the Paul Sartori Foundation attended P’s address, apparently with the purpose of creating the advance decision.

c. [P] was highly distressed in her conversation with the individual from the Paul Sartori Foundation and, essentially, signed the document merely to bring the conversation to an end.

d. [P’s daughter] considered that [P] did not understand the contents of the advance decision or that it had legal effects.

e. While the advance decision purports that [P] was witnessed signing it by her neighbour, [the neighbour] was not present during the signing, and was only approached afterwards to co-sign beside [P’s] name.

Further evidence was therefore sought. The judge authorised a Third Party Disclosure Order in respect of the Paul Sartori Foundation; evidence from the neighbour who signed the document; and further wishes and feelings evidence from the litigation friend, who intended to take a physical copy of the advance decision to P and discuss it with her. Evidence was also still awaited from the GP to shed light on any relevant clinical issues at the time when the ADRT was made, which could assist in assessing P’s capacity at that time. (Her daughter was reported to have said something at the Round Table Meeting to the effect that “mental decline may have been well underway”.)

Counsel for P also raised the issue of “whether [P] has done anything clearly inconsistent with the advance decision remaining her fixed decision (s.25(2)(c)” – e.g. agreeing to admissions to hospital; and whether circumstances exist now which P did not anticipate at the time she made the ADRT and which would have affected her decision making had she anticipated them (MCA s. 25(4)(c)).

The judge said that under the circumstances, “I don’t think I could safely make any findings [about the ADRT] without further enquiry”. He reiterated that at the end of the hearing: “Having read the bundle yesterday afternoon, I didn’t think the evidence was adequate for me to make any kind of finding on the advance decision”.

Towards the end of the hearing, P’s daughter spoke powerfully about her perception of what had happened. She described a situation in which her mother had discharged herself from hospital.

“Mum had bad legs and they started to swell. I called the GP and a paramedic practitioner came out and he asked her, ‘what do you think about resuscitation?’. And he said, ‘Are you sure? Do you know what it entails?’, and she said, ‘No, I don’t want it’. Then a woman from Paul Sartori turned up. I didn’t ask her to come. Mum didn’t ask her to come. She called herself an ‘End of Life’ adviser. Mum was very agitated about this. She spent an hour and a half in my mum’s house and my mum just wanted her gone, and so she signed it. She thought ‘end of life’ was about giving her a bed in the living room, making her more comfortable, that sort or thing. She didn’t know what that document meant.”

In addition, some ongoing concerns about P’s weight were expressed – although this seems to have improved slightly and she was apparently enjoying marmalade sandwiches. There was also a need to address her refusal to take medications.

The next hearing, at which the evidence would be available, and the judge would be able to make a decision about the ADRT, was set for 3rd November 2025.

2.3 The November hearing

At the hearing of 3rd November 2025, there was agreement between the parties in court (although the daughter chose not to attend and I gather she didn’t submit a Position Statement either) that P’s presentation had continued to improve, albeit slowly. She’s eating and drinking a bit more, and seems more settled and less distressed. Someone reported moments of “happiness”: at one point she’d been singing along to “Oh, Pretty Woman”.

On the ADRT front, counsel for P had produced a detailed, thorough and carefully structured analysis of why he invited the court to decide that the ADRT was not a valid or applicable document. This was supported by the comprehensive “Agreed note on the law of Advance Decisions”, which includes a “Checklist for ADRTs that refuse life-sustaining treatment”. His analysis was not challenged by any of the parties at the hearing, and it was the analysis accepted wholesale by the judge.

Counsel for P did not seek to challenge P’s capacity to make the ADRT at the time that she made it. This was because there was no assessment of her capacity at the time to rebut the presumption of capacity; the GP disclosure that is now before the court doesn’t suggest any material cognitive decline, and “while disclosure from the Paul Sartori foundation does not contain helpful evidence either way, it is a reasonable presumption that they would not make an ADRT if they felt that P lacked capacity at the time”.[xi] The daughter’s account suggested that P was using and weighing information when making the ADRT, as P was (she said) convinced she had cancer, had been close to family members who had died with cancer, and wanted the document drawn up “so she would not have to go through what they did”.11

Counsel for P invited the judge to find that the ADRT was invalid – and indeed did not reflect P’s wishes and feelings – on the grounds that neither at the time she made it, nor subsequently, has it expressed her views. The following extract is taken from his Position Statement:

§46. There is considerable evidence that the contents of the ADRT are no longer P’s fixed decision, if they ever wholly were:

a. P apparently had little input into the wording of the ADRT. [Her daughter’s] evidence is that “The nurse filled in the form and my mum signed it, mum was so agitated with it all mum refused for the nurse to read it back to her and just wanted it all over with”.

b. Immediately upon the ADRT being made, P expressed a different view to its contents. [Her daughter’s] evidence is that, when the ADRT was made, “I did say to my mum […] what if you have a stroke, and mum’s reply was do what you like [Name], if you think it’s right do it, but that was not written in the document”.

c. Two years later, P was still acting contrary to the ADRT. On 3 April 2025, P was about to be admitted to W Hospital for the second time. [Her daughter] attended and “convinced [P] to attend hospital”. This is consistent with §46(b) above.

d. Today P’s speech remains inconsistent with the ADRT. Her wishes are that “Well if I needed to go in [to hospital] that would be up to them […] The nurses. It would be up to them”.

Counsel for P concludes that “In short, as soon as the ADRT was made, [P’s] speech and actions were inconsistent with it. She was not, as the ADRT purports, set against hospital admission in all circumstances. Instead, she wished (and still wishes) for admission decisions to be taken by those she trusts. Previously that was [her daughter]. It now includes W Nursing Home staff”.

Nobody contested this position – that the ADRT was invalid under s.25(2)(c) of the Mental Capacity Act 2005, the section that says: “An advance decision is not valid if P […] has done anything else clearly inconsistent with the advance decision remaining his fixed decision” (“anything else” means anything other than withdraw it when they had capacity to do so, or confer the relevant authority on the donee of a Lasting Power of Attorney, which are (a) and (b) respectively of s.25).

In court, counsel for P explained again what P had done that was “clearly inconsistent” with the advance decision being her fixed decision. She had acquiesced to hospital admission. She had displayed what he called “a deferential approach” to her daughter and (now) to her carers, conceding to them the right to decide whether or not she should go to hospital.

And on that basis, the court was invited to declare the ADRT invalid.

Strictly speaking (said P’s counsel), applicability only falls to be considered if there is a valid ADRT in place (which he maintained there wasn’t in this case). But even if the judge were not to accept the analysis above, and were to consider the ADRT validly made, there are difficulties relating to applicability. There was no witness signature. The litigation friend had reported on a telephone conversation with the neighbour who’d signed the ADRT as an apparent “witness” to P’s signature. She confirmed that she had not in fact been present when P had signed it.[xii] As a result, to the extent that this document would otherwise be applicable to life-sustaining treatment, it is not applicable as it does not meet the requirement of s25(5) and (6) of the MCA.

The purported ADRT also doesn’t apply to treatment requiring hospital admission that is not life-sustaining, said counsel for P, because at the time she made the ADRT, P believed she had terminal cancer. She did not anticipate her current circumstances where “there is no evidence of any terminal condition. She experiences happiness at W Nursing Home, chatting and singing with staff”. As such, there are reasonable grounds to believe that, had P anticipated her current circumstances on the date she signed the document back in 2023, that would have “affected” her decision. There are then, in the words of the MCA, “reasonable grounds for believing that circumstances exist which P did not anticipate at the time of the advance decision and which would have affected [her] decision had [she] anticipated them” (s.54(4)(c) MCA).

Finally (said P’s counsel), it is unsafe to rely on the ADRT as evidence of P’s historic wishes and feelings (such that even if not binding, it could be used in making best interests decisions) because “the evidence is that P did not write the ADRT, did not know what it was, immediately expressed an approach to treatment different to its contents, continues to express that approach now, and has acted contrary to the ADRT since it was made”.

Judgment

The analysis above, as set out by counsel for P, is effectively the analysis adopted by the judge in his unpublished oral judgment. The judge said: “the whole document seems to me to be highly questionable”. He accepted that there was insufficient evidence to rebut the presumption that P had capacity to make an ADRT at the time she made it. He also drew attention to evidence that the ADRT may not have been signed in the presence of the next-door neighbour who is the purported witness of P’s signature: he said, “it’s a mystery to me why the person preparing the document didn’t provide a witness signature for her”.

He was also of the view that “it’s most unclear whether or not in fact [P] was intending to sign such a document at all: she was concerned about a possible illness that didn’t materialise in any event”.

Addressing the question of validity, the judge said:

“The issue here is whether [P] has continued to ‘follow’, if I can put it that way, the intentions that are said to have been expressed in the ADRT. It seems to me that she has frequently acted in quite the opposite manner to what was expressed in that document. I am particularly mindful of evidence from [her daughter] that when the document was prepared, she refused to have it read back to her. It is highly likely that in fact she didn’t really understand what the terms of that document were. The court has received no notes [from the Paul Sartori Foundation] to support what may have been said about the content to her or anything that may explain why the document wasn’t witnessed at the time. There are questions about how this document was prepared. We may never know the answers to those questions.

In the months following this document being prepared, she behaved in the opposite way to the intentions expressed. There is no doubt in my mind, having read the submissions, that this document should be deemed to be invalid. It’s a document that to my mind has never been followed and never pursued in any meaningful sense by P, and everyone involved in her case – including her daughter who is very close to her – has said she’s never followed this.

My judgment is that this is not a valid document, and there should be appropriate documentation placed on her medical records to show that the ADRT must not be relied upon.”

3. Reflections

It’s often a concern that someone who simply downloads a form off the internet, ticks a few boxes, and signs it, may end up with a document that does not reflect their intentions, and/or one that does not withstand legal scrutiny. That’s why people often seek out professional support.

Charities like the Paul Sartori Foundation offer vital expertise and advice to people wanting to make advance plans about care and treatment at the end of life. But, on the face of it, the judgment in this case is a rather serious indictment of their services. The finding of the court is that a capacitous (albeit distressed) elderly person was visited by someone who drew up a document that she didn’t understand and which didn’t properly convey her wishes. I don’t know whether that analysis is correct or not, but it’s what the court decided.

Everyone I know who works in the area of advance care planning is deeply committed to ensuring that the person’s own wishes are properly recorded. From my own experience of supporting people making advance care plans, I think it’s possible to misjudge the situation – especially when you don’t have access to the person’s medical records and are dependent on what they tell you. Unlike family members and friends, you get a ‘snap-shot’ of what the person is like, their values, wishes, feelings and beliefs, over a relatively short period and across just a few visits. And there’s so much to explain! I can’t begin the tell you the number of times the starting point of a conversation has been “I don’t want to be kept alive if I’m a vegetable”, and we have to unpick things from there. It’s a complex conversation. There are so many different possible future scenarios (especially if in fact the person does not have a diagnosed terminal illness), and such a wide range of different possible treatments to be considered (some of which, like clinically assisted nutrition and hydration, many people consider not to be treatments at all, but part of basic care).

I’ve also seen in my own voluntary work in this area, that people will sometimes say one thing to me about the treatments they want to refuse, and another when family members join the conversation. The effect of making an ADRT is to insist on making a decision oneself, thereby over-riding the best interests decisions that family members might otherwise be invited to participate in. This can sometimes be painful for family members, especially when they disagree with the decisions someone is making. There have been many times when an elderly person has told me (for example) that she wants to refuse life-sustaining treatments and her adult children have pleaded with her not to “give up”, to “stay alive for us because we love you”. “My daughter can’t cope with it – she wants her Mum to live forever”, someone told me, asking me to record that her daughter’s views about what treatments she should have are not her own views, and that she wants her views to prevail. Others are more “deferential” to family members, and insofar as this is an important value to them, we explore the option of Lasting Powers of Attorney for Health and Welfare, with some “preferences” filled in on the form.

For me as an older person with an ADRT (refusing all life-sustaining treatment unless I have capacity to consent to it), my biggest fear is not that it will be applied in circumstances where I don’t intend it to apply, but rather than it will not be enforced when it should be. I’ve written more about that in a blog post ( Determining the legal status of a ‘Living Will’: Personal reflections on a case before Poole J) reflecting on another ADRT case where that’s exactly what happened. The ADRT wasn’t disclosed to medics for 4 months, then wasn’t considered applicable to P’s situation, then was subject to accusations from his family that it was fraudulent or the product of undue influence, before finally the judge ruled it valid and applicable and treatment was withdrawn. (I made some suggestions about how to protect ourselves against that scenario here: “Authenticity of a living will’.). Once these cases are in court they seem often to take so long to resolve. I don’t understand for example why the Third Party Disclosure Order against the Paul Sartori Foundation wasn’t made sooner, or why the daughter’s evidence didn’t really seem to be part of the story until the week before the third hearing in this case.

Of course, the courts should be open to the possibility that an apparent ADRT is not valid, not applicable, not authentic – and in doing so they may (as the judge believes himself to be doing in this case) protect vulnerable people against a situation they had never envisaged arising. In relation to this case, counsel for P said that it’s “rather wonderful that P is doing better than she perhaps ever would have anticipated”.

Equally though, some of us are terrified that our ADRTs will not be respected and we’re struggling with how to demonstrate that we have thought of every possible future situation that might arise, lest our ADRT be rendered invalid on those grounds. My particular concern, highlighted by this case, is how to protect my capacitous self who is making decisions now against my possible future incapacitatous self who might behave in ways “inconsistent with my advance decision remaining my fixed position”. I want my capacitous decisions to overrule my future incapacitous wishes and feelings – but it seems that the law is not with me on that.

The decision in this particular case (heard by a district judge) is an outcome of the filtering down to the district courts (where the vast majority of Court of Protection cases are heard) of a High Court judgment. It’s not a precedent authority for judges making decisions in future, but rather a worked-out example of legal decision-making about ADRTs in the light of (amongst other case law) the judgment from a senior (High Court) judge, Mr Justice Poole, in Re PW (Jehovah’s Witness: Validity of Advance Decision) [2021] EWCOP 52). The idea that the actions of your incapacitated future self can override the otherwise binding decisions you make when you have capacity derives from that judgment. I’m sure there will be other cases like this in the district courts. There may already have been some I don’t know about. The lack of transparency in court lists makes it impossible to systematically locate and observe ADRT cases – for example, the lists for this case never referred to the hearing as being about an ADRT and I’d never have known had I not discovered it by accident.

Finally, this case does raise some key questions for charities, and anyone else who assists people with making ADRTs. What can we do to be as sure as we can that the person is signing a document that reflects their true wishes – and that they understand the consequences of projecting their decisions forward into an uncertain future? How can we best “future-proof’ ADRTs against circumstances we can’t currently imagine? How do we record and document our involvement with the people we help in ways that are likely to be useful to the Court of Protection if necessary? I hope some of the individuals and organisations involved in advance care planning will take up this invitation to respond.

Celia Kitzinger is co-director of the Open Justice Court of Protection Project. She has observed more than 600 hearings since May 2020 and written more than 100 blog posts. She is on LinkedIn (here), and also on X (@KitzingerCelia) and Bluesky @kitzingercelia.bsky.social)

[i] A day in the life of a court observer: The high cost of open justice

[ii] https://paulsartori.org/acp/

[iii] https://paulsartori.org/advance-care-planning-resources-links/

[iv] https://paulsartori.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/My-future-care-and-medical-treatment-Easy-read-PDF.pdf

[v] There was an earlier hearing which I did NOT observe, which I think was the first attended hearing in the case, on 11 July 2025.

[vi] We are not allowed to audio-record the proceedings, so everything in this blog post that purports to be quoted from what was said in the hearing is based on my contemporaneous touch-typed notes. They are as accurate as I could make them, but unlikely to be verbatim.

[vii] I am grateful to Jordan Briggs, counsel for P via her litigation friend, for preparing for the court the very helpful “Agreed Note on the law of advance decisions”: he is, of course, not responsible for the way I have used it! I am also grateful to the judge who spontaneously made the observation that this would be useful to me and authorised its disclosure.

[viii] Judges have usually treated capacity to make an ADRT as synonymous with capacity to make treatment decisions and have deployed a presumption of capacity to retrospective capacity assessment (see Alex Ruck Keene’s analysis here: https://www.mentalcapacitylawandpolicy.org.uk/advance-decisions-to-refuse-treatment-presuming-a-presumption-of-capacity/)

[ix] I am grateful to DJ Keller for consistently ensuring the transparency of these hearings.

[x] Quoted from the Position Statement submitted by Pembrokeshire County Council (the mistake relating to “advanced” – rather than “advance” decisions is in the original).

[xi] From the position statement for P

[xii] This person had not submitted witness evidence so it was merely “hearsay”, admissible in the COP, said counsel for the local authority “where the person has no skin in the game and no reason to lie”. Counsel for P said that “strictly speaking, if you rely on hearsay evidence there is a requirement to get permission in advance under 14.2(d)”. I did wonder why there wasn’t an actual witness statement (as opposed to the litigation friend’s account of what was said in a telephone conversation), but I don’t suppose it would made any substantive difference.

A “deferential approach” and its implications for an ADRT?

Thank you for this blog – It’s obviously a complex case and I hope will provoke a lot of discussion. But as someone with experience of supporting a loved one with an ADRT, the part that hit home for me was the discussion of P’s “deferential approach” and the way this was used (albeit as just one strand) in an argument against the validity of an ADRT.

I suspect I’m not alone in witnessing a loved one with a deteriorating condition become increasingly deferential as they became more dependent, and as their capacity to understand, retain or weigh information declines.

This blog suggests that acquiescing to medical intervention under such circumstances could contribute to invalidating an ADRT because it might be used as evidence of behaviour inconsistent with the ADRT remaining the person’s fixed decision.

I find that very worrying.

My mum had professional insight into the problem of spirals of treatment escalation (especially in old age) and had very strong views on this. She wrote her own Advance Decision to try to protect herself from over-treatment at the end of life. But as dementia eroded her capacity to process information she became an uncharacteristically compliant patient. At one point, for example, she acceded to a doctor’s suggestion that she be taken into hospital in circumstance that she never would have consented to in the past, and which her ADRT explicitly refused. I could not see anything in the situation itself that might have led her to ‘change her mind’. I considered asking for a formal test of her capacity to give consent and then (assuming I was right that she’d lost the relevant mental capacity) insisting that her ADRT be followed – but that felt impractical in the time scale and, also, humiliating for my mum. So, instead, I reminded my mum (and the doctor) about what she’d written in her ADRT and asked my mum about her current thinking in relation to her previously expressed concerns. She responded by immediately retracting her assent/consent. The doctor, for his part, changed tack to focus on palliative care at home.

I have no idea whether the doctor saw this incident as an example of supported decision-making to refuse, a best interests decision or an outcome determined by the ADRT – or perhaps simply as family manipulation. Whether or not this decision was ‘right’ (or made in the right way), my point is that without my questioning of the proposed course of action, my mum would have been taken to hospital without any resistance. I suspect this happens to a lot of people. Reading this blog makes me worry that a frail person’s increasing compliance could be used as evidence of actions inconsistent with prospective decision-making to undermine an otherwise valid and applicable ADRT.

This doesn’t seem right to me.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I also have a mother with dementia. I have LPA for Health and Welfare and although the document does not include any specific instructions, she has always made her wishes in relation to her current situation crystal clear. I would really fight for these wishes. And yet, my mother made other wishes clear that I am more conflicted about.

She was always a very well turned-out, elegant woman. Whenever discussions about failing faculties and deteriorating health came up, she would reiterate her issues about burdensome treatments, but also beg me to make sure that she always had her hair put up every week and never went out without make up. I gravely assured her that I would carry out these wishes. Her non-capacitous self isn’t bothered about hair and make-up and sometimes resists even basic personal care.

I have talked to her about this and, in fact, I suspect that she might just about pass a capacity assesment for decisions about hair and make-up, but that might be wishful thinking. I suspect that maybe I too am guilty of letting a current non-capicitous statement override previous capacitous instructions. This is rather ironic as I am currently livid, dismayed and deeply worried about this judgment. (I will take a few days to calm down before commenting!)

LikeLike

The Clinical Governance Committee of the Paul Sartori Foundation would like to thank Celia Kitzinger for sharing her information about this case with us.

We are concerned that we were not invited to be present at the court proceedings which denied us the opportunity to explain our practice in more detail. We are seeking legal guidance as to how to proceed and are unable to offer further information at this point.

LikeLike