By Virginia Gough, 23rd November 2025

The protected party (P) is a man with autism and a hoarding disorder. The Local Authority has deemed his property in need of urgent clearance and attempts to achieve this previously have not been successful because P has remained at the property and ‘progress was too slow to be meaningful. He resisted the removal of certain items and progress was extremely limited.’ At a hearing last month, the judge was asked to authorise P’s removal from his home – either by agreement or by force – to enable them to clear the property, assess the amount of work that is required to make the place habitable, and complete any necessary remedial works. At that hearing, the local authority made an application for a two-stage order: the first stage was for P to be “encouraged” to leave the property. Stage 2, contingent on Stage 1 being unsuccessful, was for authorisation of removal with restraint. The judge authorised only Stage 1 at the last hearing. (see Hoarding and best interests challenges for the Court of Protection by Claire Martin).

There was one feature of the 7th October 2025 hearing which was (intentionally) omitted in Claire Martin’s report of it and which we feel is important to report on now. There were actually two different versions of the judge’s order of 7th October 2025 – one for the public bodies (which referred to Stage 2) and one for P and his brother (which did not mention Stage 2). Both versions were discussed in a public hearing, and there was nothing in the Transparency Order preventing the observer from reporting this. Since the creation of two different versions of the order was clearly an attempt to withhold certain information from P (and his family), Claire (the observer) and Celia Kitzinger (the blog editor) decided together to wait until after P had moved – or been moved – out of his house to report on this. Celia says: “In effect, the court relied on us being responsible court reporters – but it would be wise to bear in mind in future that with an observer present in a public hearing, and no reporting restrictions to prevent disclosure, there is always a risk that information might be published and discovered by P and his family, contrary to the intentions of the court. I urge the court to amend the Transparency Order in cases like these”. She also comments: “I am not sure how the ‘two versions’ of the order really works in any event, given that orders from public hearings are themselves public documents (COP Rule 5.9). I would previously have advised family members that (unless they are specifically told otherwise) an order from a public hearing would be complete and accurate – but now I have to contemplate the possibility of redactions, even in orders from public hearings. I’m not sure this was properly thought through”.

Following the hearing observed by Claire, Stage 1 “persuasion” was attempted, but P refused to leave his home. Subsequently, Stage 2 was approved, on 14th October 2025 (we think without a publicly listed hearing). However, in the event, P left his home on the 20th October 2025 without the use of the authorised restraint plan.

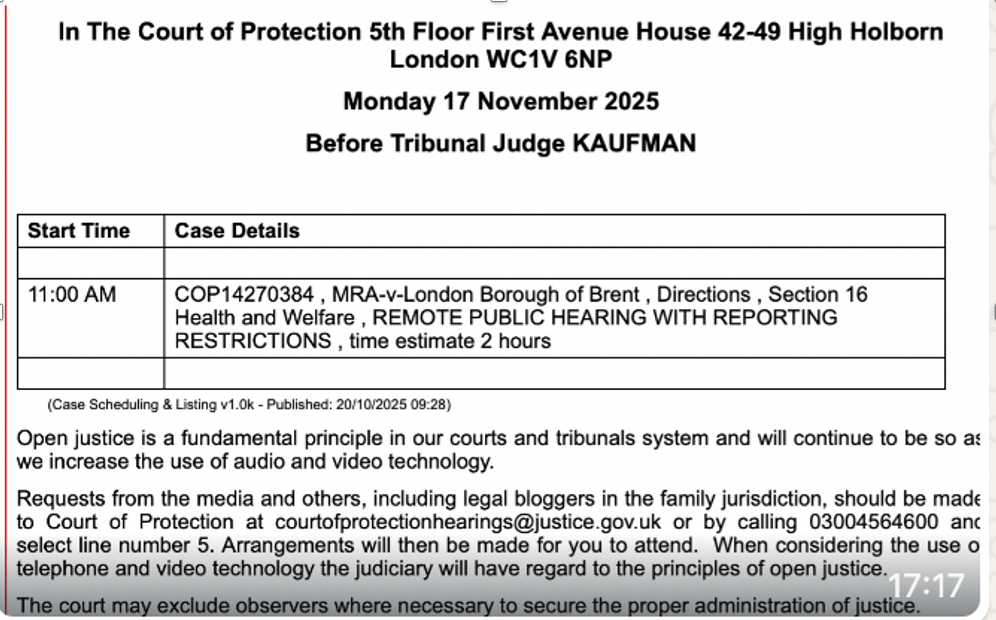

The next hearing we saw publicly listed was on Monday 17th November 2025 (a bit sooner than had been anticipated, according to Claire Martin’s blog post). It was at 11am before Tribunal Judge Kaufman, and that is the one I observed and report on below.

Hearing of 17th November 2025

At the hearing, P was present, in the same room and on the same screen as counsel representing him (via the Official Solicitor), Mary-Rachel McCabe. The Local Authority (London Borough of Brent) was represented by Alexander Campbell. (P’s brother appeared not to be present at this hearing.)

For the benefit of those observing, the Local Authority provided an updated background since the previous hearing when the order for removal with restraint was approved.

On 20th October 2025, P moved out of his home without the use of restraint, and into a hotel in the local area (for the purposes of this post, let us call it Hotel A), which he was familiar with from a previous stay. This move had gone well – which, as the Judge clearly expressed toward the end of the hearing, was the result of the consideration and time put into the process in the previous two hearings.

However, the placement at Hotel A has had to come to an end. The reasons for this were not made entirely clear, the Local Authority referred only to ‘insurmountable logistical difficulties’ regarding payment.

As a result, P has had to move again, into another local hotel (I will call it Hotel B) at his own expense. The Local Authority has been searching for a suitable property since then and has now found a flat available for P’s use – but it is some distance away in another area of London. They have kitted this out with towels, pillows, a microwave and other items to make it habitable, and it has been available since 6th November 2025.

The Local Authority wants an order to move P into that flat, with the same transition plan in place as previously authorised. This includes the multi-stage order from verbal encouragement at first, progressing to restraint subsequently.

The Official Solicitor opposed this application as the flat is not in P’s local area, and he would find such a move destabilising. In addition, the property only has a shower, and P’s particular needs require use of a bath. Additionally, the Official Solicitor opposed the use of restraint for this move as disproportionate.

The Local Authority offered a number of arguments for why this move, although not ideal, would be in the best interests of P:

- This accommodation is preferable to that of a hotel as it is more secure, particularly as P is currently self-funding at Hotel B. There is, therefore, a risk of a financial need to end the stay, or a risk that the property will become fully booked requiring P to leave at very short notice. At that stage and urgency, the Local Authority may find it difficult to find any suitable accommodation, or to purchase needed items to make the accommodation acceptable for P. The Local Authority is seeking more reliable accommodation.

- There are also benefits to the specific property the LA has located. As a private dwelling, it is a more personal setting than that of a hotel. It will allow P to live independently as it has better facilities, such as a food preparation area and microwave.

If the Court agrees to order the move to the flat, the Local Authority will continue looking for a more suitable property in P’s local area. The Local Authority did recognise that for P it would be preferable to avoid multiple moves but stated that this is unavoidable as there is nothing better currently available.

The Judge asked Counsel to specifically address the evidence from the Mental Health NHS Trust (although not represented at this hearing, they were involved previously and both the Judge and Counsel for the Official Solicitor referred to and quoted from a written report provided by them) which stated that P’s specific needs meant moving out of the local area would be challenging.

LA: ‘If we had found somewhere in his local area, that would be what we were asking the Court to authorise today. But there was nothing suitable in the area. The evidence provided by the Trust recognises the benefits of P remaining in his local area, and whilst the Local Authority would not dispute these, the evidence does not suggest that living in a different part of London would be an absolute barrier to receiving the ongoing support and care. It may be more difficult but, in my submissions, those do not outweigh the benefits of more secure accommodation.’ [Counsel for the Local Authority]

The Local Authority emphasised that if P had to move out of Hotel B urgently, the accommodation found at that point may be even less convenient: this was a significant risk they wished to avoid.

Then the Official Solicitor provided the following reasons for why the move is unsuitable for P:

- The primary reason is location. The property is a signficant distance from P’s local area. In fact, when looked up by the Official Solicitor, it is over an hour and 15 minutes on public transport – depending on the route – requiring two or three changes. P relies on local individuals, shopkeepers and his GP. He requires the stability brought by consistent routines. He has lived in the local area for most of his life.

- Multiple moves are not advisable for P. Counsel for P stated: ‘P requires stability as much as is realistically possible. That position also reflects the conclusions of the doctor who diagnosed him, who stated a need for ‘scaffolding and structure.’ In other words, stability is important.’ The move from his home to Hotel A was possible due to his clear involvement in the process, careful planning and the fact the Hotel A was already known to him and in his local area. This is not true of the other property.

- Additionally, whilst this is a less important factor, P has been unable to tolerate having a shower throughout his life and requires a bath.

The Official Solicitor recognised that asking the Court to effectively authorise the continued payment of Hotel B out of the pocket of P was an ‘unusual’ one, but pending the identification of more suitable accommodation, this was preferred. The Local Authority would then have to continue to search, and it was requested that the order include a particular responsibility of the Local Authority to update and communicate regularly with the Official Solicitor about available accommodation to ensure P could be involved in this process.

Additionally, the Official Solicitor was keen to request that restraint be removed from the order as an option for removal. The use of restraint had been discussed at length with regard to removing P from his own property urgently. However, Counsel described it as ‘disproportionate’ outside of that urgent and particularly difficult context. The proposed move from Hotel B is significantly different, and as it is a private hotel, there are some limits to the authority the secure ambulance service has to force entry, which had not been properly considered by the Local Authority.

Judgment

The Judge apologised to P for the disjointed and unsettled process of moving him out of his property. She expressed concern that these circumstances would not be putting him in a positive position to move forward from the clearance of his property. However, beyond answering yes or no to a question asked by the Judge regarding his planned attendance at an upcoming important appointment, P did not make any oral contributions expressing his own views at any point in the hearing.

The Judge also re-emphasised how unfortunate additional or gratuitous moves are for P and recognised that whilst hotel accommodation is deficient in many ways and it is concerning to think P will ‘remain in hotel accommodation for a long time’, the Local Authority plan itself involves possible further moves beyond the flat now under consideration, if a more suitable property is found.

The judge found, in conclusion, that the risks of residing in a hotel were not particularly weighty and she did not authorise the move to the property proposed by the Local Authority.

The Judge did order that the Local Authority file evidence about the continuing search for an appropriate property and must keep the Official Solicitor updated as to the efforts and outcomes of the search. This will be discussed at the next hearing.

Costs application against the Local Authority

Additionally, the Official Solicitor had made a costs application in the week prior to the hearing, for the costs arising from the additional work resulting from the failure of the placement at Hotel A.

Timelines for the Local Authority to respond to this cost application were set in the course of the hearing. The Local Authority wanted until the morning of Friday 21st November to respond to the application (over a week), on the basis that the individual who had received it was out of office at the time and their legal and social work teams were to be focused on finding accommodation for P. The Official Solicitor requested the Local Authority response and evidence at the end of the working day on Thursday 20th November. As stated by the Official Solicitor, these additional few hours would be important to ensuring they could respond fully. The Judge gave the Local Authority the timeline they requested, with the explicit direction that she did so to provide them additional time to make ‘extensive effort’ to find suitable local accommodation for P.

The application is set to be discussed in full at the next hearing, which was last confirmed to be listed for 11:00am on 25 November 2025.

Virginia Gough is a student at City Law School, currently studying the Bar Vocational Course following completion of the Graduate Diploma in Law. She is pursuing a practice in Family Law and Court of Protection. Her interest in mental capacity law and the specific challenges of advocacy for vulnerable individuals stems from her volunteer work as a Social Security Tribunal Representative, where she represents clients appealing decisions on disability benefits. She is a new contributor to the Open Justice Court of Protection Project, and this is her first blog post. You can connect with her on LinkedIn.

This is a very useful account of the difficulties faced by clients who have a hoarding disorder and another diagnosis or disability. I have advocated for a number of people whose desire to return home after a hospital stay, or moving out of their home temporarily, has been thwarted. I am curious to know why there was no timetable for the work on Ps home to be completed because the Judge could have made an order for this to reassure P that his move would be temporary.

I currently have a case which involves an 85 year-old man deprived of his liberty for 18 months, placed in a care home, whilst a family member has used POA to empty his bank account. The LAs housing department is dragging out the process of finding him a home even though the LAs housing department has made him homeless and failed to protect his property and personal effects.

As an IMCA, I am not sure where to turn or what to do next and I hope maybe one of the lawyers who reads this post might be able to point me in the right direction.

LikeLike