By Jenny Kitzinger, 9th December 2025

When someone lacks capacity to make a will, it’s possible to apply to the Court of Protection for a will to be made on their behalf. It will be made in their best interests under s.18(1)(i) of the Mental Capacity Act 2005. These are called “statutory wills”[1].

In 2022, I applied for a statutory will on behalf of my sister, Polly Kitzinger. It was a simple and uncontested case. The judge decided it on the papers, without a hearing – as I understand is the case with most statutory wills. That means no observers and no Transparency Order to tell everyone what they can and cannot report. The proceedings are essentially ‘private’, and section 12(1)(b) of the Administration of Justice Act 1960 applies – meaning we can’t publish anything about it. I can only write about Polly’s statutory will here because we applied, and were granted, permission of the court. How we did that will be the subject of another blog post.

Not all applications go as smoothly as Polly’s, and hearings do take place when there’s a dispute. They sometimes appear in the public listings and then they can be observed and reported. In the first part of this blog post, I report on a case listed as concerning “whether the court should authorise the execution of a statutory will”. An elderly woman with dementia was at the centre of a family conflict about who should inherit what. It was a complicated and painful situation, involving an estate valued at over £1 million, which included the family farm and it’s still not resolved as far as I know.

There’s a problem with publishing only information about statutory wills that result in hearings. By definition, these are the most challenging – often contested – cases. My aim here is to document some of the complexities in a disputed application (the case I watched concerning the family farm, COP 13947478) and also to demystify a routine case (my application for Polly, COP 11757133). As I’ll show, even a straightforward application that’s decided ‘on the papers’ has emotional complexities and administrative challenges – albeit not to the same degree as cases resulting in hearings.

Part 1 describes the contested hearing I observed.

Part 2 sets the hearing I observed in the context of my own experience of a much more straightforward application.

Part 3 reflects on the process of making a statutory will application and considers the costs and benefits of doing so.

I’ve not been able to find any published accounts from other family members about applying for a statutory will – probably due, in large part, to reporting restrictions which make only anonymised reports lawful. My account of the experience is potentially useful, in my view, partly because some family members (including lay deputies and people holding power of attorney) may never have considered the possibility of making this kind of application. Others may be aware of statutory wills, but hesitant to apply because they are daunted by the legal process involved, anxious about creating family divisions, or concerned about their own “conflict of interests”. Unlike professional deputies, a lay person who might apply for a statutory will may well be a potential beneficiary and/or in family relationships with others who might benefit from, or be ‘disinherited’ by, a statutory will. Making a statutory will application means having to live with any stigma or blame associated with the outcome.

I hope that this account of my own experience might both inspire others to think about the pros and cons of making a statutory will application, and also alert lawyers and judges to what statutory will applications can be like for lay people – and to consider whether the process can be improved.

Part 1 – A contested statutory will: “Mrs P”

The Open Justice COP Project has published only two previous blog posts about statutory will hearings: “An emergency statutory will for a dying man” and “Judge approves statutory will in contested hearing”. We were unable to observe another case, held in private, concerning a multi-millionaire with severe dementia (“Secret justice”). So, given my personal interest in statutory wills, I was pleased to be alerted to another hearing (COP 13947478) listed in Courtel/CourtServe to consider a statutory will application on 6th June 2025.

The protected party (Mrs P) is in her early eighties and she’s been diagnosed with vascular dementia. Until about three years ago, she lived at home with her (second) husband on the family farm. He died a few years ago, and she moved into a nursing home.

Mrs P has a daughter from her first marriage, and two stepsons from her second marriage. In 2019 she appointed one of her stepsons (“S”) as her attorney for both property and affairs and for health and welfare – and it was he who was making the application for the statutory will.

Counsel for the applicant, was Daniel Currie (St John’s Buildings); counsel for two of the respondents (Mrs P’s daughter and other stepson) was David Green (Atlantic Chambers). The protected party (Mrs P) was represented, via the Official Solicitor, by James Kirby (Lincoln’s Inn).

Mrs P’s last will was made in 2005. She and her husband made mirror wills, each appointing the other as executor and giving each other the entire estate. If the other did not survive, the wills gave the farm to S (Mrs P’s stepson) on condition that he live there and farm the land for five years. The residuary estate was to be divided equally between Mrs P’s daughter and her other stepson. When her husband died in 2022, this meant that Mrs P inherited the farm and all the couple’s savings and investments.

Shortly after her husband’s death, Mrs P attempted to make a new will. Her wishes at that point seemed to be that S should be her main beneficiary and should inherit the farm, but that her other stepson, and her daughter, should not benefit. She wanted her grandchildren (her daughter’s children) to benefit instead. She was not able to make a will to this effect because a capacity assessor found that she lacked “testamentary capacity” (the specific capacity needed to make a will[4].

Nobody disputes the finding that Mrs P now lacks capacity in this area of decision-making. Without a new statutory will, her previous will, made in 2005, is what will determine how her assets are distributed.

This was the situation that led Mrs P’s stepson, S, to apply to the court for a statutory will to be approved by a judge, on behalf of Mrs P – and he had drawn up a draft for consideration.

The statutory will drafted by Mrs P’s stepson gives the farm to him – as does the 2005 will – but unlike the 2005 will, the new draft proposed that neither Mrs P’s other stepson (his brother) nor Mrs P’s daughter would inherit from her estate. He proposed dividing the residuary estate 80% to him and 20% to Mrs P’s grandchildren. This bears some relation to what seem to be Mrs P’s most recently expressed (but non-capacitous) wishes though her alleged wishes are disputed by Mrs P’s daughter and the other stepson who are the second and third respondents in this case. Their view is that the previous (2005) will should stand, and that there is no need for the court to make a statutory will.

There’s another source of contention too. In his role as her attorney for property and affairs, S has spent more than £200k of Mrs P’s money renovating the farmhouse. He says the renovations were undertaken in her best interests to enable her to return home – which the local authority deems to be in her best interests. He also did much of the work on it himself, losing earning potential by so doing. It was confirmed in court that Mrs P is shortly to return home with live-in care. However, Mrs P’s daughter and other stepson dispute the extent to which the renovations were in Mrs P’s best interests and note that if S is to inherit the farm, he would personally benefit from this expenditure. Of course, the cost of renovations also reduces the value of the residuary estate (from which they were due to inherit under the 2005 will) – and it is also being reduced by Mrs P’s ongoing care fees (she’s self-funding). This will become even more of an issue going forward given that the cost of Mrs P’s care will increase when she returns home.

At the time of the hearing, the Official Solicitor (representing Mrs P) had organised a Court of Protection Visitor to meet with Mrs P and find out her current views. The OS had then put forward a proposal for a statutory will which was different from both the 2005 will and from the will proposed by S. The Official Solicitor’s proposal was for a will which did leave some money to Mrs P’s daughter and the other stepson (the one not inheriting the farm) and also took into account the reduction of the residual estate (by, for example, the money spent on the farmhouse). In addition, it included various elements which were designed to reduce the risk of a conflict between S’s interest as legatee and his duties as Mrs P’s LPA, and measures to reduce the scope for further disputes between Mrs P’s potential legatees during her lifetime (all relevant elements to considering Mrs P’s best interests).

However, none of the family members agrees with the Official Solicitor’s proposals. The daughter and the stepson who doesn’t inherit the farm argued that there was no need for a statutory will, and that that the 2005 will should stand: if the court does decide on a statutory will, they want a larger bequest from Mrs P’s will than is proposed by the OS. Meanwhile S is concerned that the fixed financial bequests the OS proposes should go to Mrs P’s daughter and other stepson could mean (depending on Mrs P’s future care costs) that they cannot be met from Mrs P’s liquid assets and that the farm would have to be sold. He says that selling the farm “contradicts totally the express wishes and feelings of every conversation he’s ever had with her”.

The parties are all represented by lawyers in court. I didn’t hear from any family member directly, but it’s clear that relationships between family members are strained. Obviously, a contest about the statutory will is unlikely to enhance family relations or support any ability to work together to support Mrs P. It must be painful, for example, for Mrs P’s daughter that her stepbrother has collected witness statements from Mrs P’s hairdresser, and from her friends and neighbours, in support of his contention that the relationship between mother and daughter was poor.

The hearing also revealed how knotted and tangled such cases can be. A will may include provision for passing on a family asset like a farm (perhaps passed down through many generations) and involve blended and multi-generational families (with children, step-children and grandchildren) and different types of inheritance arrangements which mean some inheritance might be fairly secure (or even enhanced by money being spent on them) whereas others are uncertain or depleted (as in the allocation of ‘residue’ from the estate). There may also be very different levels of involvements in care, different impacts of the care set up on potential legatee’s ability to earn, and disputed views about the nature of relationships.

The parties have agreed to mediation. If it fails there will be a two-day hearing at the end of 2025 or beginning of 2026.

Observing this case made me very aware of how complex wills can be – and how this is amplified when it comes to writing a statutory will, especially if there is conflict between potential beneficiaries.

It also made me reflect on my own experience of applying for a statutory will – and why in some ways it was so simple, and why, in other ways, it still felt so very difficult.

Part 2 – Applying for Polly’s (uncontested) statutory will

The aim of my application in May 2022 was to update a previous will my sister Polly had made 18 years earlier (in 2004) when she’d taken out a joint mortgage with her partner to purchase a lovely cottage in Wales – the first time Polly had owned her own home. She and her partner moved in together with great excitement and joy and wrote ‘mirror wills’ making one another each other’s primary beneficiary.

Five years later (in 2009), Polly was involved in a car crash which left her with devastating brain injuries. She now lives in a nursing home entirely dependent on 24/7 care. She lacks capacity to make her own decisions about, for example, medical treatment or where she lives and has profound physical disabilities too which severely limit her life and (originally at least) were expected to severely reduce her life-expectancy. An expert report in 2010 predicted she’d be unlikely to live beyond 2020.

The primary beneficiary of her original will, her partner at the time, was at Polly’s bedside almost every day of the eight months that Polly was in hospital following her car crash in 2009. She continued to be involved after Polly moved to a specialist neuro-rehabilitation centre and then on into long term care. But she eventually went on to rebuild her own life without Polly. In 2011 she sold their cottage and moved away, transferring Polly’s share of the equity into Polly’s bank account – an account that I manage as Polly’s finance deputy. She removed Polly from her own will in 2013 and has since married someone else. She chooses to have no contact with Polly any more. Her family is sure Polly would have wanted her partner to get on with her life in this way (and, indeed, some other members of Polly’s family made similar choices).

In this situation it seemed appropriate to consider a new will for Polly to take into account her changed circumstances. It also seemed clear that she couldn’t rewrite the will herself (nobody doubted but that she would be found to lack testamentary capacity), so it would be in her best interests to rewrite the will for her, which means making an application to the Court of Protection.

Making a statutory will, involves – like making any other best interests decision – consideration of the person’s past and present wishes and can also take into account a range of other issues such as inheritance tax, the potentially shifting value of different gifts (e.g. a farm versus the residue of the estate), or risks of (future or ongoing) family acrimony and litigation. You can see some such considerations in the Mrs P case I observed. None of these issues applied to Polly as her situation, and her finances, were very straightforward.

In thinking about the terms of a new will, I already had Polly’s 2004 will. That will, not only makes her partner her primary beneficiary, but also says what should happen if her partner died before her or the legacy failed for any other reason. Polly has no children or dependents: her will stated that if her estate did not go to her partner, then it should be equally divided between me and one of her other sisters, Tess (choosing the two of her four sisters with whom she had particularly close relationships). She had named me as her executor.

I tried (with little success) to ascertain how Polly felt about her will now. I then discussed options with Polly’s family and the one friend of Polly’s who has stayed in touch with her situation. Might, for example, Polly now have wanted to leave her money to charity? The consensus from those close to Polly was that in her new circumstances Polly would have wanted the money to go to her ‘second choices’ in her 2004 will – i.e. me and her other sister, Tess – both of whom are still directly involved in Polly’s life.

The appropriate course of action seemed to me fairly clear and, as Polly’s finance deputy, I have a duty to administer her finances in her best interests. But, in fact, I didn’t get around to applying for a statutory will until 2022 – arguably almost a decade after I should have done. I suspect I am not alone among lay people in this tardiness, so it’s probably worth reflecting on why such delays might happen.

2.1 Why I delayed applying for a statutory will

My failure to apply for a statutory will for many years after I was aware that it was appropriate to do so was partly because there were just too many other things to do. Polly went from one crisis to another, and I was very focused (especially in my additional role as her welfare deputy) on trying to ensure all medical interventions were in her best interests and, in particular, that decisions took into account her strong previously expressed wishes. I was working closely with my sister, Celia Kitzinger, to understand medical law and practice in this area. It was very time-consuming to try (and repeatedly fail) to ensure compliance with the Mental Capacity Act 2005 in situations where some medical staff seemed unfamiliar with the Act or unwilling to comply with it.

A great deal of effort was also needed to join up crucial aspects of Polly’s routine day-to-day care and for this I was working closely with my sister, Tess Kitzinger-McKenney. We felt that sisterly and welfare deputy input was needed in relation to a range of issues from trying to ensure care staff followed specialist guidelines about hoisting and correct positioning in her wheelchair to attempting to control her chronic pain. For many years, Polly also had episodes of “challenging” and “aggressive” behaviour – and sometimes only the presence of Tess or me would calm her; being with her was also particularly important for medical appointments (to ensure continuity, provide accurate history, convey correct information across sites etc.).

So I’ve lots of practical excuses, but I have to admit that my delay in sorting out Polly’s will was not just because of these challenges. I was also hesitant because of the potential conflict of interests. Over the many years since her brain injury, I’ve often argued in favour of ceilings of treatment for Polly (informed by evidence of Polly ‘s own wishes). This has sometimes prompted healthcare staff (mostly those unfamiliar with Polly or her family) to suggest that I want Polly to die so that I can inherit her money. Examples of this include (during one of Polly’s emergency re-admissions to hospital) a loud conversation between nurses in a corridor about my alleged financial motivations for resisting the reinsertion of her feeding tube – a conversation which seemed deliberately pitched at a volume that I could ‘over-hear’. During the same hospital admission, I returned to Polly’s bedside after nipping to the toilet to find a typed note stuck up above her bed. It was a quote from the bible that read: “The eternal God is your refuge, and underneath are the everlasting arms. He will drive out your enemy before you, saying, ‘Destroy him!’“.

Under such clouds of suspicion, and sometimes outright hostility, I felt more comfortable knowing that I wasn’t going to benefit from her will; it was her ex-partner (as long as she out-lived Polly) who would get everything.

2.2 Finding ‘the right time’ to apply

By 2022 updating the will felt long overdue. I knew that when Polly died (and she had already lived longer than originally predicted), I’d have failed to act on this aspect of her best interests. In particular I was sure that Polly would have wanted to leave money to Tess given the way that involvement in Polly’s care over the preceding 13 years had negatively impacted on Tess’s employment opportunities.

I was also aware that leaving the 2004 document as Polly’s last will and testament would put her ex-partner in an awkward position and leave a difficult situation for me at a time when I’d probably be dealing with layers of ‘complex grief’ myself.

By late 2021/early 2022 some pressures had also eased off. It felt like there was a bit of ‘breathing space’ because Polly’s placement seemed stable and her medication and nursing care well managed. She also finally seemed to be becoming more ‘settled’ . The “challenging behaviour” so evident for over a decade had become much less frequent: she’d become generally compliant, and there were fewer crisis calls.

I also wanted to get around to sorting Polly’s will at this point as I was acutely aware that our father (in his mid 90s) was needing increasing support and I thought that my role as his financial LPA and as his executor might become a big demand in the near future.

As it turned out not only did our father die the following year, but both Tess and I needed hospitalisation for our own medical issues. In the same year, Polly’s placement deteriorated after key staff left, including the excellent home manager and Polly’s wonderful key worker. A general staffing crisis followed. Then a CQC inspection found residents were at risk of abuse and neglect and the home was closed down. We had to move Polly with 28 days notice, and the only place we could find, and that the CHC agreed to pay for at the time, was a dementia unit.

Sometimes I’m grateful not to have a crystal ball to know the future. But – given what happened in 2023 – certainly 2022 was the window of opportunity that needed to be taken if an application for a statutory will were to be made!

2.3 Submitting an application – the practical steps

In early 2022 I looked up how to apply to get approval from the OPG for a statutory will on the government website here: https://www.gov.uk/apply-statutory-will

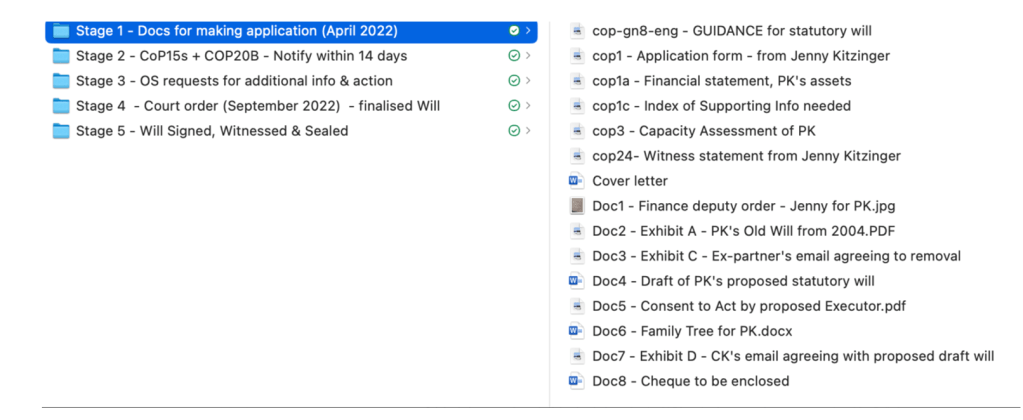

I set up a new OneDrive folder and all the sub-folders I’d need matched against the Office of the Public Guardian forms and labelled a bright yellow ring-binder ‘Statutory Will’ – with an optimistic sense that it should not be too difficult.

I wasn’t completely naïve – I’ve dealt with a lot of legal, financial and medical forms as Polly’s deputy – so I expected to face some unfamiliar language (I’d already had to look up the legal meaning of ‘engrossed’) and I also thought I might sometimes get in a bit of a tangle. To cheer me on my way I pinned up one of Polly’s cartoons above my computer. Polly had sent me this when she was a student; it captured the difficulty she was having writing an essay, caught in a tangle of vocabulary. This little sketch made me smile each time I looked at it, and provided a bit of sisterly solidarity from the past.

The application process started well. How to apply for a statutory will is clearly explained on the government website: https://www.gov.uk/apply-statutory-will. To start with, there’s an 8-page generic COP1 form to complete. This details the nature of your application. An explanation of each question and how one might answer it is helpfully included at the end of the form

The application also needs to include an up-to-date professional assessment of the person’s (lack of) ‘testamentary capacity’ (the COP3 – ‘Assessment of Capacity’ form) and a draft of the proposed statutory will.

Assessing testamentary capacity: I commissioned an experienced psychiatrist who works as a Special Visitor for the CoP to assess Polly. She examined relevant medical documentation and met Polly to assess her and to attempt to ascertain Polly’s current feelings about her will. This was not an easy task. Polly has profound cognitive and communication difficulties which can make it hard to interpret what she might be feeling or what she might know. For example, she recognises her own name (and the names of her parents and sisters) but quite what she knows or ‘recognises’ about herself and her family is unclear even though she seems to trust us. It certainly seems that she has little or no memory of her adult life, no understanding of her current condition and is unable to retain significant new information (such as the death of her mother). The expert assessment was consistent with our expectations. It found that, as a consequence of her brain injury, Polly was unable to retain any information for more than a few seconds or to weigh choices against each other. It also found that “Ms Kitzinger is not oriented to her own situation”, doesn’t understand “her own living situation, care needs or financial affairs”, did not know who she had been in a relationship with previously and that she specifically lacked the capacity to make a will.

Drafting the proposed statutory will: In order to provide the court with a draft statutory will I went beyond my early informal conversations from years earlier to formally consult those who knew her, and I again attempted (without much success) to ascertain Polly’s own wishes and feelings. I found getting back in touch with Polly’s ex-partner an emotional hurdle to overcome as we hadn’t been in contact for a while and I knew she found it upsetting to think about the trauma of Polly’s car crash and its aftermath. She was very willing to help however, and made it very clear she had no expectation or wish to inherit from Polly and that she supported the proposed re-writing of Polly’s will. There was a clear consensus from all concerned that the statutory will should simply remove Polly’s ex-partner so Polly’s money would go to me and Tess as the primary beneficiaries. I also proposed adding, that, if either of us died before Polly, each of our portion should go to Tess’s children (Polly’s much-loved niece and nephews).

Forms about finances, family tree and other facts: In addition to the CoP1 (application form), COP3 (Capacity form) and the draft will I needed:

- COP1a ‘Annex A form “Supporting information for property and affairs applications” – this provided information about Polly’s assets

- COP1c form “Supporting information for statutory will, codicil, gifts(s), deed of variation or settlement of property form”.

- CoP24 form – my witness statement about why a statutory will was needed.

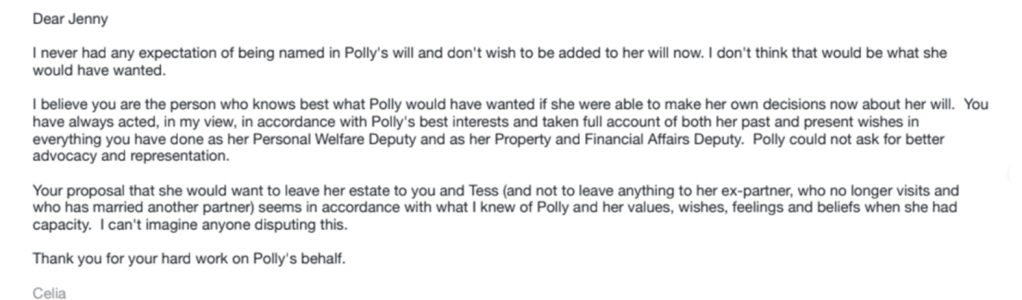

I also had to submit Polly’s original will from 2004 and a family tree showing Polly’s family connections, along with statements from people who might be seen (at least by the OPG) as having a reasonable expectation to inherit. See below for an example, a statement from my sister Celia confirming that she had no expectation, or wish, to benefit from Polly’s will.

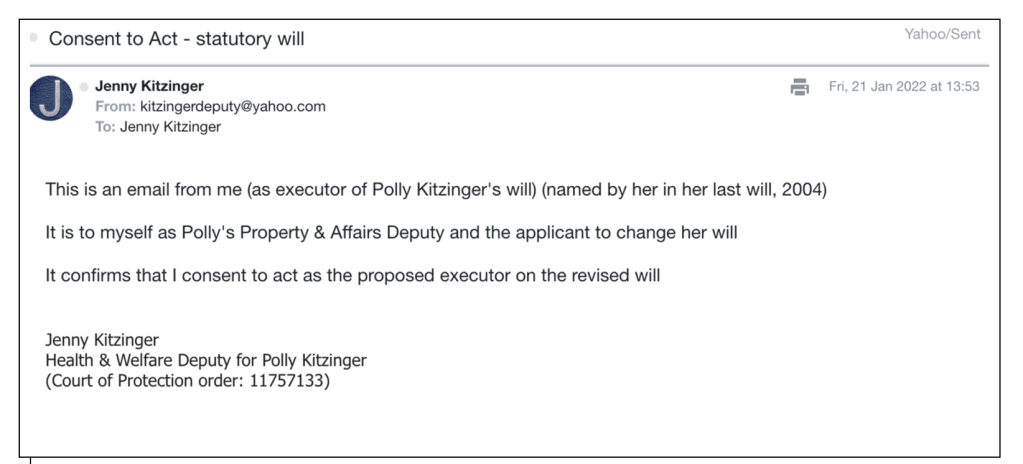

Finally, I needed to provide evidence of ‘consent to act’ in relation to the executor of the new will. See the rather convoluted email below that I ended up writing to myself as evidence for this purpose!

My computer folders for stage 1 of the process (putting together the documents for the application) is shown in the screenshot reproduced below. You can see “Docs for making application” is one of my folders on the left – and everything I needed for the application is listed in the right-hand column.

You’ll also see from the screen shot that there were several further steps to go through before the will was finalised and sealed (authorised) by the court.

But at this stage (Stage 1), I was just relieved to print everything out (as apparently paper copies had to be submitted) and to enclose a cheque to cover the (approximately £400) fee for the application. The requirement for a cheque was one of the more surprising aspects of Stage 1 given that I hadn’t used one for many years. But I eventually found an old cheque book, took everything down to the post office and then went straight to a café for a ‘reward’ of hot chocolate and a slice of lemon-drizzle cake.

2.4 Action needed between submitting the application and the order authorising me to execute the will

I submitted the application to the CoP on 8th April 2022. On 25th May 2022, an order was issued (by DJ Beckley) ordering that Polly be joined as a party to proceedings and inviting the Official Solicitor to act as Polly’s litigation friend. The case number assigned was COP 11757133-04.

I was pleased to see that DJ Beckley’s order emphasised the need to resolve the matter as quickly as possible and with the minimum possible expense to Polly (referring to Rule 1.1 of the Court of Protection Rules 2017). It set a deadline of 17th August 2022 (almost 3 months from the date of the order) by which time the court should be notified whether it was likely that the parties would reach an agreement, when they’d be able to file a proposed consent order and whether a hearing would be needed.

I then received a letter from the Official Solicitor accepting the appointment, stating her fees (£228 to £360 plus VAT per hour), and asking for further information.

At this point there was a bit more work for me to do as the applicant. This was in relation to three forms:

- COP15 forms – “Notice that an application form has been issued” – had to be sent to relevant parties (this included Polly’s ex-partner and my sisters, but also Polly’s niece and nephews). This gave them the opportunity to be joined as parties and they could have intervened if they wished. (In the case of Mrs P it may have been this process which alerted her daughter and other stepson.)

- COP20B form – this needed to be sent to the OS, confirming that I’d served the COP15 forms.

- COP14 form – this had to be sent to Polly (with a copy to the OS) notifying Polly that the OS had been appointed as her Litigation Friend. I completed the form and posted it to Polly at her care home. I opened the envelope myself a few days later when I visited and read the form out to her and explained it to her as she stared into space. I tried again another day – but she appeared rather disinterested.

I also had to serve ‘the Official Solicitor and each party’ with the application and copies of all the documents I’d submitted to the court. To my surprise there seemed to be no shared system for lodging and sharing such documents efficiently. I also had to go back to some paperwork at this point as the letter from the OS explained that the OS found it useful to have documents in word format rather than pdfs (a lesson learnt there – I now always try to ensure I store word versions of documents as well as pdfs).

An unexpected and difficult bit of paperwork for this part of the process was the request from the OS for an up-to-date assessment of Polly’s medical condition which should include “an assessment of life expectancy, and the likelihood of Ms Kitzinger requiring increased expenditure in the foreseeable future for their care need”.

The letter from the OS stated this was ‘ordinarily’ provided in the COP3 form – but, in fact, the COP3 form did not have a section spelling out the need for this particular information and it had therefore not been included in the assessment I’d commissioned. Nor could I see how such information could possibly impact on whether or not the statutory will I had proposed was in Polly’s best interests. I surmised at the time that the question might be relevant for life-time gifts and that I’d just been sent a standardised letter. Having observed the Mrs P hearing, I now realise it is also relevant where a will might give an asset such as a house to one beneficiary and the ‘residue’ of the estate to others as life-time expenditure (related to how long someone lives and their care costs) will impact on the value of the residue. However, this was not relevant to my proposal for Polly’s will.

The request from the OS was also not an easy request to fulfil as no one now seemed willing to make an assessment of Polly’s life-expectancy. But I eventually persuaded Polly’s GP to provide a verbal statement.

I got all the second set of paperwork I had to provide back to the OS by 30th May and then waited. On 18th of August 2022 the OS emailed the court saying there was no intention to do detailed submission – and attaching a 3-page summary of what I’d demonstrated. The OS said the proposed statutory will was in Polly’s best interests and attached a draft order for the judge.

On 23rd September 2022, the Court sent me the ‘approved’ draft will. This was the same as the draft will I’d submitted but with some numbering added and some necessary phrasing added at the beginning and end of the document (see below). The order from District Judge Ellington (made 2nd Sept, issued 23rd Sept 2022) stated that “upon reading the draft statutory will (initialled by District Judge Ellington for the purpose of identification)” and reading other relevant documents she authorised me “to execute a statutory will in the terms of the said draft”.

2.5 Getting the statutory will signed and sealed

At this point it was ‘just’ a question of getting the will signed, witnessed and sealed. The format of the approved will was as follows. The opening lines that had been added to the draft I’d prepared stated: “This is the last will of me POLLY KITZINGER of [her placement address] acting by JENNY KITZINGER the person authorised in that behalf by an order dated the [date] day of [month, year] made under the Mental Capacity Act 2005“.

At the end of the draft statutory will there was the addition of an ‘Attestation” reading: “In witness of which this will is signed by me POLLY (MARGARET) ALEXANDRA KITZINGER acting by JENNY VANESSA KITZINGER under the order mentioned above on [date]“.

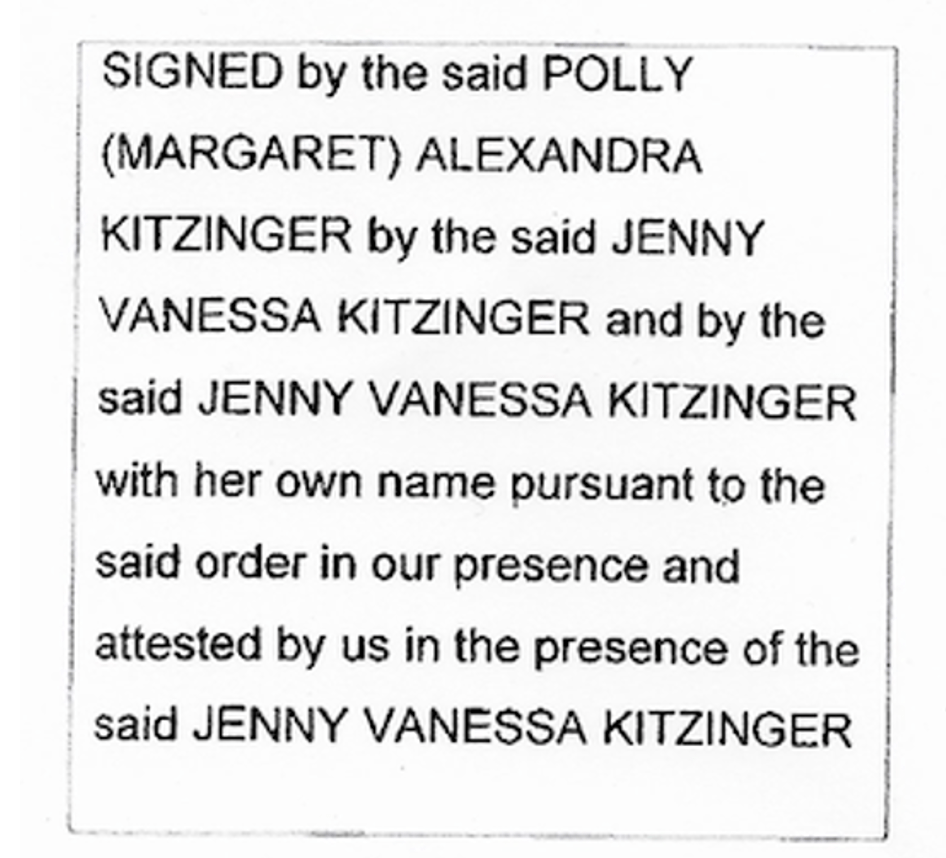

This was followed by a box which read as follows.

I was a bit baffled by some of this phrasing but worked out that I should sign twice (once as if I was Polly, using her name). The two witnesses to my signature then added their signatures (and name, address and occupation). I then added a ‘certificate’ to the end of the will as instructed in the format below – which also had to be signed by me.

“I/We hereby certify that this will is an exact copy of the draft thereof as approved by the Court

Signed………

Dated……..”

I had to have two copies bound (the will was just one page, but signatures took it to two pages long) and sent it for sealing.

Unfortunately, it was subsequently returned unsealed as the copy of the will I used was the approved copy sent to me by the court with the judge’s initials on it. So I was told to redo all the signing and witnessing on a copy without the initials and go through that bit of the whole process again!

The will was finally back with me in November 2022 (about 8 months after I started the process), with the addition of an embossed imprint on the pages and the words “Sealed with the official seal of the Court of Protection 15th November 2022”.

My application was a long drawn-out out process. It’s possible to make an emergency application (e.g. when P is dying), and these can be dealt with amazingly swiftly, although of course there is always the risk of these applications being resolved too late.

Part 3 – Reflections

Statutory wills can involve very complex issues and therefore be challenging to apply for, and to secure. I was lucky in that it was relatively easy for me given the simplicity of Polly’s financial affairs and the lack of any family tensions about what a statutory will should say. Nevertheless, parts of the process were difficult.

Emotional toll: I’m in a family where everyone can talk easily about death (and money) so the subject of will-writing itself was not taboo and we’d lived for a very long time with the expectation of Polly dying. However, the application involved quite a bit of emotional labour.

- The need to think about what Polly would have wanted, and try to access her current wishes, is core to what I do as Polly’s deputy but it’s always hard, whatever the decision. This is because her current situation is so far from anything she would have wanted, and because her ability to process, express, (or obtain) what she might currently want is so very limited.

- For this particular decision I also had to approach relevant people who no longer had contact with Polly in order to consult, or at least inform them, about the application. This was difficult because I knew that this would cause distress. It clearly upset her ex-partner, for example, who although fully supporting the application also subsequently wrote to say she’d found it traumatic to have to re-engage with anything about Polly. She wrote to say she was sure we would do the right thing in relation to Polly and hoped she could be completely left out of any future consultations and court proceedings.

- A part of the application process which was also stressful was the need to seek out up-to-date life-expectancy predictions as requested by the OS for the statutory will application. I was not surprised that it was hard to get anyone to answer this question, nor did it surprise me that her GP eventually responded by confirming that although Polly might die very soon (e.g. from pneumonia) she might also live a normal life span. It was upsetting, never-the-less, not least because it underlined the fact that Polly might outlive her sisters and be left without what little protection and support we’re able to provide.

Ill health and other challenges to come: The emotional context therefore had its challenges but I also remember the application process and paperwork just feeling overwhelming at times. This is surprising in some ways as I had a demanding job and am used to putting together major and very detailed research applications. While writing this blog, I went back and checked the dates and realised I was also beginning to become ill in 2022 with an (at the time) undiagnosed condition which needed major abdominal surgery the following year. Neglecting one’s own health needs is not uncommon among families supporting someone with profound disabilities and my medical condition probably also undermined my resilience and efficiency. Although early 2022 had felt like a good window of opportunity to apply for the statutory will, other pressures also built up during the months that the process dragged on, including problems with Polly’s day-to-day care. Looking back, I can now see why I was so demoralised when the will ‘boomeranged back’ because I’d submitted one which had the judge’s initials on it and another copy (without the judge’s initials) needed to be re-printed, re-signed, witnessed, and returned. This was a relatively simple process, of course, but I’d thought it was all sorted and was desperate to tick off this task among all the other tasks I needed to do.

Death by a thousand papercuts: The general context of administrative burden is also probably relevant. Applying for a statutory will is one more administrative task among a plethora of others – and another one that sits in one’s in-tray for weeks or months (or even years!) as other organisations go through their own processing of the paperwork. Being a deputy (or/and an LPA or an executor) can involve lots of unfamiliar paperwork which, I suspect, can take anyone close to the edge of their own tolerance or competence. I often made mistakes and had to work hard at proof reading and avoiding basic errors. The anthropologist, David Graeber’s, book on ‘The Utopia of Rules’ and his account of ‘structural stupidity’ provides insight into how this happens! A lot of energy went on coping with the everyday frustrations too: printer paper jammed, ink ran out, attachments disappeared, computer glitches thwarted me. In addition, the interface between myself, the OS and CoP did not always go smoothly. Everyone was trying to be helpful but the application system seemed old-fashioned or unclear at times (e.g. the need for a cheque book or the request for word versions of documents at a point when I’d only saved them as pdfs). Interactive forms also didn’t always work e.g. the COP3 form would not accept the capacity assessor’s electronic signature: she’d never had this problem when dealing directly with COP3 forms for lawyers – so maybe they have some magic software. In addition, I had the sense that I was dealing with professionals under a lot of pressure themselves – I was informed that a new case management system was “bedding in” and errors were made at their end (I think) which in turn put a series of micro-anxieties on me e.g. a ‘password-protected’ document arriving without follow-up passwords; a document with a request to sign and submit to the Court that arrived after the deadline for submission had passed, and a letter (the one containing the final sealed will) which was initially delivered to a neighbour’s address as the house number had been mistyped. Also, three years later, I have still not been sent an invoice so that I can pay the Official Solicitor for the work she did on Polly’s case (despite recently receiving an email “enclosing the Final Cost Certificate for your attention” and telling me an invoice would arrive by post “soon”). This makes additional work for me as Polly’s finance deputy – recording the debt in my returns, ensuring I’ve kept funds aside to pay it, awaiting the invoice in the mail every day now and wondering when to chase in case it’s gone to wrong address. In the course of writing this blog I’ve reluctantly come to the conclusion that I’d recommend (if affordable) employing someone to help make an application for a statutory will. I’d recommend this even if it looks like you can do most of it yourself, and would still have to work alongside any professional you employ, and it doesn’t take away all the challenges – at least you’ll have someone who’s done it before, knows the process, has the right software interface and can support at least part of the process.

Surveillance and submission: The added context here is one in which one can sometimes feel powerless in relation to many (hard-pressed) institutions supposed to be supporting one’s vulnerable relative (e.g. health and social care provision) and where the OPG and COP role in safeguarding can sometimes feel like suspicious micro-management and another drain on the family love and energy rather than a supportive protection. Mark Neary has written very powerfully about this, documenting his experience as Finance Deputy for his son. He makes explicit the tensions that can arise between making things work for his son in his role as his father on the one hand and fulfilling the demands of the OPG on the other. He also highlights the impact of ‘micro-management’ and of the ‘tone’ with which the OPG can approach family members. He describes, for example, a conference in Leeds where ‘the top dog in the Property & Affairs Deputyship department at the OPG’ gave a talk which consisted of “anecdote after anecdote of family members ripping off their vulnerable relatives. The hero and villain roles were bluntly cast and all Deputies learn over time that they are not seen as a reliable, loyal Woody, but as a sinister, Stinky Pete, who is ready to sell out his friends for his personal gain at the drop of a stetson.” Mark Neary adds: “My memory of the first few years of deputyship was of a time of constant anxiety; expecting the woman from Leeds to arrive at my door because I mislaid the receipt for The Proclaimers greatest hits CD.” [“Woody Gets A Partner”]

When a system is set up to ‘protect’ P, it needs to not just safeguard against abuses but keep in mind the need to protect (or at least not drain and undermine) any positive support network around P. The devil is in the detail. It has to go beyond reiterations of the so-called ‘overriding objective’ to deal with the matter expeditiously and fairly and at proportionate cost (Civil Procedure Rules 1.1). That can only happen if the bureaucratic process works smoothly.

Was it worth it? A zero-sum game in family energy? Making the application means I have fulfilled my duty in relation to Polly’s best interests around her will. I’m glad the application succeeded and it is one less thing to deal with in the future. But I have regrets. When I started the application process, I did not know that both Tess and I would soon need major surgery, nor that, during that time, there would be a rapid deterioration in Polly’s placement and that Polly would end up in a dementia unit, losing access to specialist neuro input, rapidly followed by losing her CHC funding. I wonder if this cascade of events might not have happened in the same way if our energies had not been so depleted at the time. Did the effort I put into navigating the safeguards put in place to ensure any statutory will was in Polly’s best interests leave her more vulnerable to being at risk of neglect and abuse in her placement? Did my pursuit of an arguably peripheral part of her best interests (what would happen after she died) mean I took my eye off the ball to protect her current best interests, or at least leave me dangerously overstretched and at risk of reduced vigilance (especially once my own health issues kicked in)? Family energy to support any ‘protected party’ is a zero-sum game. Juggling priorities and knowing that sometimes we will fail has become a necessary part of the journey – and sometimes that may mean not pursuing something that, ideally, we should.

In conclusion, I am glad that that the option of creating a statutory will does exist in England and Wales (it doesn’t in Scotland and many other jurisdictions). I endorse the value of statutory wills as part of a 360-degree assessment of best interests – and think they are a valuable tool in some, but not all, circumstances – both for practical and for principled reasons. In Polly’s situation the principle of ‘updating’ her will in line with what we thought she’d want in her changed circumstances was pretty straightforward (and also clearly in her best interests). But I agree with Rosie Harding that there are different issues at stake when the Court of Protection is asked to write a will in the ‘best interests’ of someone who’s never had testamentary capacity, or for a person who has previously had testamentary capacity, but who is intestate.

If you are in a position of making an application to the court for a statutory will, I think the guidance offered on the OPG website is helpful and the forms are generally well-designed. In many ways the system seems to be working well, and there is clearly a judicial commitment to making the process transparent – a commitment reflected in, and contributed to, I hope, by this blog post. In hearings I observed, I’ve seen the Official Solicitor carefully try to navigate a resolution in cases of family conflict (as in the case of Mrs P), and I’ve seen how a judge can quickly and effectively address best interests where there is unresolvable conflict in an emergency situation (as in the case of Mr R, the dying man I wrote about in an earlier blog). I’m also grateful that the judge who assessed my own application concluded that it did not need a hearing and could be decided on the papers – thereby avoiding what could have been an expensive and time-consuming extension to the process. This seems a proportionate and sensible way of approving some uncontested statutory wills without overburdening the court system.

One of my aims when I set out to write this blog was to share my experience to help others understand the process and perhaps feel less daunted by it. In the course of writing it, I have come to realise that another outcome may be to forewarn people entering into the process who may perhaps imagine that it might be be rather more straightforward than it is likely to turn out to be in practice. While encouraging everyone to consider whether they should be applying for a statutory will, I would also warn any lay person against taking on trust that the process is as simple as the initial instructions make it appear. As I hope this blog has illustrated, even a very straightforward application can have its complexities for the person making it and for the other people implicated in the decision. I don’t want this blog to deter anyone from making a statutory will, but I do hope it will help them to pace themselves and be prepared for some of the challenges.

At an institutional level I don’t think I have any big ideas for improvement beyond the general point about the need for efficiency, sensitivity, and minimising any unnecessary requests or disproportionate obstacles – but I would welcome any feedback from those working with the OPG or COP if this blog post prompts any thoughts from their perspective.

Jenny Kitzinger is co-director of the Coma & Disorders of Consciousness Research Centre and Emeritus Professor at Cardiff University. She has developed an online training course on law and ethics around PDoC and is on both X and BlueSky as @JennyKitzinger

Footnote

[1] For more information about the law on statutory wills see “Statutory wills: A barrister explains”. For practical guidance and access to the relevant forms see the government website: https://www.gov.uk/apply-statutory-will/getting-a-decision (and “Age Space” also gives helpful guidance here). For academic analysis of statutory wills and discussion of case law see: Harding, R 2015, ‘The rise of statutory wills and the limits of best interests decision-making in inheritance’, Modern Law Review, vol. 78, no. 6, pp. 945-970. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2230.12156 (Author’s version: click here). Milward K, Curtice M, Harding R. Statutory wills: Doing the right thing under the Mental Capacity Act 2005. BJPsych Advances. 2017;23(1):54-62. doi:10.1192/apt.bp.116.016022

It’s so useful to have the court processes mapped onto personal experience like this. It’s only when you have to map the procedures onto your real life experience that you see all the pitfalls.

I was surprised, for instance, to see that the Official Solicitor was involved in this uncontested and apparently quite unremarkable application – at a cost, of course. I had never even heard of the Official Solicitor until, as deputy for my mother’s financial affairs, I made what I thought was a simple application about gifting. I also had no idea that another capacity assessment would be needed, although it was quite clear from my deputyship application that there was no way my mother had capacity. I abandoned the application at that point!

In hindsight I am more able to see that things that were obvious to me might not have been so obvious to the court but the mismatch between bureaucratic procedures and lived experience is tough on those who have nothing but P’s best interests at heart. And while every i is dotted and every t is crossed when P’s interests come before the court, I wonder what is happening to so many other Ps whose cases the court knows nothing of. For instance, as the blog post you link to points out, the Office of the Public Guardian goes through the expenditure of deputies with a fine tooth comb whereas those exercising Lasting Powers of Attorney are almost never subject to oversight.

I quite see why in hindsight you wonder whether you should have bothered!

LikeLike