By Celia Kitzinger, 18th January 2026

My sister, Polly Kitzinger, was a protected party in the Court of Protection concerning a statutory will. You can read a detailed blog post by Jenny Kitzinger about why – as Polly’s sister and as her Deputy – she made an application to the Court to approve a statutory will for Polly, and what the process involved: Applying for a statutory will: Observation and personal experience.

The court proceedings about Polly’s statutory will were decided back in 2022 but, until last month (December 2025) we weren’t allowed to publish anything about the case. Doing so would have been contempt of court.

We had to keep the proceedings about Polly’s statutory will secret because the judge (District Judge Ellington at First Avenue House) made her decision ‘on the papers’, i.e., by reading the application and the supporting evidence, and the submissions of the Official Solicitor, without hearing any oral submissions. Many decisions in the Court of Protection (especially financial ones) are made like this – ‘on the papers’, without hearings: it’s a relatively efficient and cost-effective way of dealing with uncontroversial applications. But it means that the proceedings are private.

In this blog I’ll explain:

(1) why cases decided ‘on the papers’ are private and can’t be reported;

(2) why we wanted to publish about Polly’s statutory will proceedings as a matter of public interest, and why we believed Polly would have wanted us to do this; and

(3) how I went about making the application to publish.

I hope this may be of assistance to others who want to publicise court decisions made on the papers.

1. ‘On the papers’ proceedings are private

Since 2016, with the launch of the Transparency Pilot, hearings in the Court of Protection are mostly held in public with reporting restrictions (the so-called ‘Transparency Order’) to protect the privacy of the person at the centre of the case (Practice Direction 4A)[1]. That’s what makes it possible for observers to attend hearings and blog about them.

But when a case (like Polly’s statutory will case) is decided ‘on the papers’, by a judge sitting privately in her chambers reading the paperwork, there’s no hearing. When there’s no hearing, there’s no Transparency Order – and so when judges make decisions in this way, the proceedings are essentially ‘private’, and section 12(1) of the Administration of Justice Act 1960 applies at subsection (b).

The publication of information relating to proceedings before any court sitting in private shall not of itself be contempt except in the following cases, that is to say-

(a)…

(b) where the proceedings are brought under the Mental Capacity Act 2005, or under any provision of the Mental Health Act 1983 authorising an application or reference to be made to the First-tier Tribunal, the Mental Health Review Tribunal for Wales or the county court.

What 12(i)(b) means is that when the Court of Protection sits in private (either because the judge has ordered a private hearing, or because the judge is deciding the case on the papers), it is contempt of court to publish (any) information relating to the proceedings – and possible sanctions including fines and imprisonment.

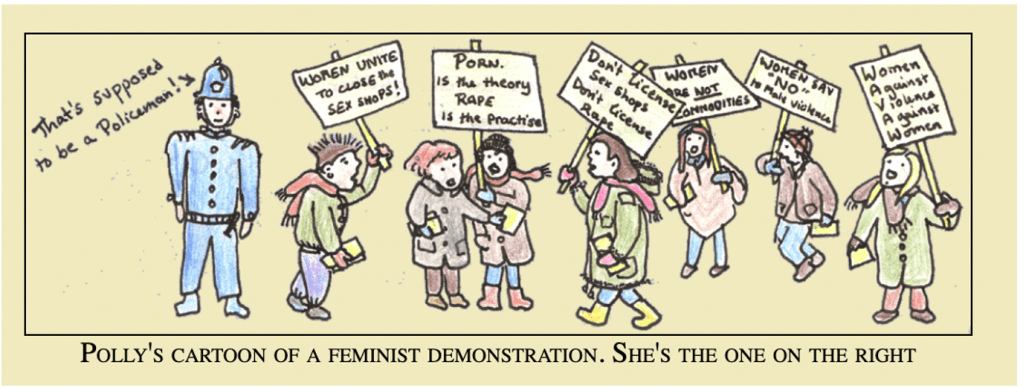

If there had been a public hearing with a ‘standard’ transparency order in place, we would have been permitted to publish information about Polly’s case in pretty much the same way that we’ve blogged about other statutory will cases[2]. The difficulty would then have been simply that it’s more complicated to conceal the identity of a protected party when you are writing about a relative, especially a relative with the same surname, and even more so when there is already information lawfully in the public domain about her, which would make it easy to ‘join the dots’. Since the car crash in 2009, we’ve published a lot about Polly – perfectly lawfully, and without breaching any transparency orders, since they only prohibit identification of someone as a P in the Court of Protection. We started long before any Court of Protection hearings with a website (welovepolly.org), chronicling her life up to that point: her adventures, her art, her political campaigning, and her advocacy for mental health patients to have their ‘voice’ heard. We’ve also spoken out about how she was given life-sustaining treatment she would have refused if she could, and about professionals’ failures to comply with the Mental Capacity Act 2005 or to elicit or show any respect for Polly’s own values, beliefs, wishes and feelings: we’ve spoken to journalists and medical ethicists, and used her story to campaign for greater awareness of Advance Decisions to Refuse Treatment[3]. So, if there had been a public hearing about her statutory will with a ‘standard’ transparency order in place we would undoubtedly have applied (as I and others have done many times before) to vary the transparency order[4], so as to be able to identify both ourselves and Polly.

The transparency order even includes within it a helpful clause saying that anyone affected by the order can apply to vary or discharge it, or for an order permitting publication of information on the basis that it is lawfully in the public domain:

But in this case, we couldn’t apply to vary the transparency order because there wasn’t one.

We had to start from scratch with an application to publish information from private proceedings.

2. Why we wanted to publish about Polly’s statutory will proceedings

Asked for the grounds on which we were seeking the order permitting us to identify Polly as a P in the Court of Protection, here’s what I wrote on the application form (a COP 9 for case COP 11757133, submitted on 7th June 2025):

“Despite not having been served with a TO prohibiting us from making information public, I would like to ensure that we do not risk being in contempt of court in writing about the experience of making a statutory will application. I believe we may need permission to publish by reason of s.12 Administration of Justice Act.

We want to write about the experience of making a statutory will application because it’s a matter of legitimate public interest. Many people don’t know that it’s possible to do this, or that there’s any point unless P is very wealthy, yet it’s part of considering P’s best interests in the round, and we’d like families to be alert to this.

We also want to challenge the ‘stigma’ around statutory wills, which we discovered clearly present in discussions about the “secret” case heard in the Chancery court by Rajah J (https://rozenberg.substack.com/p/secret-justice) and it’s also manifested as a response to blogs we’ve published as part of the Open Justice COP Project about contested hearings featuring embattled families (e.g. https://openjusticecourtofprotection.org/2025/03/27/judge-approves-statutory-will-in-contested-hearing/). There’s a public perception that the purpose of statutory wills is tax avoidance and/or family fighting over money. We have a different and probably more commonplace story to tell.

It’s difficult, given our public profile and previous publications, to write anything about Polly anonymously – and we want (as Polly would have wanted) to be able to speak publicly in our own names, which is far more likely to gain public attention and engagement”

So, as I sketched out in the application, there are two key reasons for wanting to publish about Polly’s statutory will case: (1) Public interest; and (2) Polly’s values and wishes.

2.1 Public Interest

As a consequence of making a statutory will for Polly, Jenny and I developed an interest in statutory wills as they relate to disability rights and social justice.

As we watched public hearings about statutory wills and wrote some blog posts about other families’ experiences, we came to realise how poorly understood they are, even by professionals working with the Mental Capacity Act 2005.

Raising public awareness about statutory wills is clearly in the public interest: it supports and develops understanding of the law and can thereby empower people to act on behalf of those who lack capacity to make a valid will themselves. It can also encourage people to understand why it’s important to make a will while we still have capacity to do this for ourselves, and that it might be prudent to consider, in doing so, the implications of possibly living for some years (or even decades) without capacity to revise or revoke that will.

2.2 Polly’s values and wishes

We are very confident that Polly would want us to be free to write openly about her statutory will application, as we already have about other aspects of Polly’s life and treatment since her car crash. We are supported in this by everyone close to Polly.

Since the car crash in 2009, Polly hasn’t been able to give or to refuse consent to what we write about her. The question of ‘going public’ about Polly is something Jenny (as Polly’s Welfare Deputy) specifically consulted about very soon after Polly’s injury. She asked everyone close to Polly to write letters about her to create a clear sense of what people thought was important to Polly (her values beliefs, wishes and feelings) to help inform best interests decisions. Contributors included Polly’s then-partner, her parents, her sisters, and two friends – and Jenny wrote a summary too. Originally designed for her immediate care team, this report was subsequently made available more widely after further consultation with the contributors – all of whom agreed that this should be done without concealing Polly’s identity. Jenny’s introduction to the report summarises the issues as follows:

“Since submitting the report to Polly’s health care team, various other people have expressed an interest in seeing it – in particular, those involved in framing and developing the Mental Capacity Act (MCA) and those involved in training health care workers to implement the Act. The principles of the MCA were very close to Polly’s heart: she worked first as an advocate for Mental Health Service Users, and then as a ‘Service User Involvement Development’ officer – ensuring that the concerns of service users impacted on research, policy and practice. She passionately believed in the right of everybody to be treated in a way which accorded with their own values and beliefs, and campaigned for the right of those lacking mental capacity to be heard. I believe that she would have wanted her experience to feed into the process of delivering on the promise of the MCA and would, therefore, have encouraged me to make this report more widely available.

In making this report available I have carefully considered Polly’s rights to confidentiality and to privacy. My first instinct as Welfare Deputy (and as an academic who serves on research ethics committees) was to edit the report to ensure that she was not identifiable. However, after reflection, and discussion with those closest to Polly, I revised this view to take into account Polly’s own strongly held beliefs in this area. Polly and I had discussed how anonymity can reinforce stigma: why should there be any shame attached to lacking mental capacity? Polly also believed that anonymity could mask a form of identity theft, whereby those writing about the anonymised individual absolve themselves from the responsibility of being true to the whole person.

In my experience, when Polly weighed her ‘right to privacy’ against her ‘right to be heard’ she always gave priority to the latter, and she would have wanted her current experiences understood in the context of her life as a whole. The seven other people (partner, parents, other sisters and friends) who contributed to the report share this view of what Polly would have wanted. We therefore agreed that the report should remain clearly identifiable as being about Polly.”

Polly’s family and friends knew what Polly would want from the way she lived her life, the values she demonstrated through the choices she made, and through the way she expressed herself in family discussions about liberty and social justice – including violence against women, sexual abuse, same-sex marriage, disability rights, and rights at the end of life.

If Polly had been through her car crash and hospital treatment and recovered sufficiently to analyse and present what had happened to her, then we believe she would have told her own story publicly. She loved narrative, illustrating and even writing storyboards about events in her life, and she would have wanted to publicise her story to educate people and make a political intervention. Sadly, doing this herself is not an option – and so we are certain that Polly would have wanted her family to write about her instead. The thought that anyone outside the family could stop us (such as a court putting restrictions on what could be said in reporting on a court case about her) would have left Polly beside herself with rage.

3. Making the application

It was not a difficult process, but it was tedious with lots of fiddly forms to fill in, and some uncertainty and delay created by the Official Solicitor before she eventually declined the court’s invitation to act as Polly’s litigation friend. It also caused some distress to people who would rather not have been involved in the proceedings, in particular Polly’s former partner, who has subsequently provided us with a letter to the court asking not to be contacted about any future court applications concerning Polly. We worried that having to inform Polly about the application might also cause Polly some upset – not because she would oppose it, but because in order for it to make any kind of sense to her, we would have to remind her about the car crash, her brain damage and lack of capacity, the court’s decision-making power, and her statutory will, none of which she remembers from one conversation to the next. Fortunately, she did not seem unduly perturbed. We didn’t use lawyers, so there was no financial cost attached to the application for us, but there could have been a cost to Polly if the Official Solicitor had decided to act – and we took this into account in deciding to make the application. Overall, we’re glad we did this because it means we can now tell another part of Polly’s story, and we know this is what Polly would want us to do and it accords with our own core values and beliefs too, about making the personal public and political.

Here’s what the process involved.

7th June 2025 I submit a COP 9 form seeking an order that we can identify Polly as a P in the Court of Protection case concerning the statutory will, and that we can identify specific family members, in effect disapplying s.12(i)(b) of the Administration of Justice Act 1960.

4th July 2025 I receive an order telling me to “… serve the application on all persons notified or served in the Statutory Will application and the Official Solicitor” and to“file form COP 20B by 18th July 2025”. The COP 20B forms basically inform everyone about the application and give them the opportunity to be joined if they want. They are fairly simple to fill in (once I’d located everyone’s up-to-date address) and I sent them to Polly’s former partner, her sisters Jenny and Tess, and Polly’s niece and nephews (the people involved in the original will application) as well as to the Official Solicitor. I sent a “Certificate of Service” back to the court confirming that I had done so.

Anyone who wants to be joined to the proceedings then has the opportunity to let the court know via the “Acknowledgement of service/notification” form. Only Jenny completed one (it says at the top “if you do not wish to take part in the court proceedings, you do not need to complete this form”). On a form dated 16th July 2025, Jenny ticked the box that said she consented to the application, and filled in the text box providing the opportunity to give “any relevant information you would like the court to consider”. She wrote that: “Polly would’ve actively wanted any reporting restrictions about the statutory will application lifted (and as far as I can check this with her now in her current state, I’ve seen nothing to suggest that she feels differently now). Polly was always willing to talk publicly about things other people considered ‘private’; she believed the ‘personal was political’ and particularly valued open discussion about interactions with health/social care and legal institutions.”

The judge also invited the Official Solicitor to act as litigation friend and ordered that she “shall confirm her position within 14 days of service of the application and this order”. I served the order on the Official Solicitor on 6th July 2025, so that should have meant confirmation as to whether or not she wished to act as litigation friend by 21st July 2025.

The order issued on 4th July 2025 also said, “The Applicant shall notify (herself or through an agent) Polly (Margaret Alexandra) Kitzinger personally of the application and file form COP 20A by 18th July 2025”. I asked Tess, the sister who most frequently visits Polly, and who has the best communication skills with her, to notify Polly about my application and to fill in COP 20A. The form asks: “Describe the steps you took to explain the matter or matters to the person to whom the application relates and the extent to which they understood or appeared to understand the information given. Please also describe what, if anything the person to whom the application relates said or did in response to that notification.” Tess wrote: “On Monday I took Polly into the garden and spent almost an hour with her during which I tried to communicate the facts about the application and observed her emotional responses and used some closed questions so she could indicate yes/no. It is unclear how much she understood. She gave no reaction at all to some of the information or just shrugged her right shoulder when I asked some questions. She became a bit distressed and agitated when I described the court making decisions for her – furrowing her brow and flapping her right hand away from her body. She shook her head ‘no’ when I asked if she remembered there’d been a court application about her will. She gave the thumbs up when I explained how it had been rewritten. She said ‘yes’ clearly when asked if she would be happy to have the process of the application and the court decision about her discussed in public. When asked how happy she would be for Jenny to write up what had happened on a scale of one to ten, Polly replied ‘one hundred’” (14th July 2025).

18th July 2025 Everything was submitted by the 18th July 2025 deadline. Now we waited to hear (by 21st July 2025) whether or not the Official Solicitor wanted to accept the invitation to act as Polly’s litigation friend. That didn’t happen. A new order was issued extending the time for the Official Solicitor to indicate her consent to 29th September 2025.

19th September 2025 Both Jenny (as Deputy) and I (as applicant) received an email from Mark Higgs, the lawyer and case manager acting on behalf of the Official Solicitor: it was he who had also dealt with the earlier application for the statutory will. He apologised for the delay (“due to busy-ness followed by a period of leave”) and asked for updated details of Polly’s assets, net annual income and annual expenditure in order to check that the costs of the Official Solicitor could be met (appending details of charges). He raised the possibility of a visit, and possibly a hearing, to consider the issues. Jenny responded two days later (on 21st September 2025) with information about Polly’s current financial situation, and explaining that since the time of the statutory will application, Polly had lost her Continuing Health Care funding. Jenny pointed out that: “… the potential cost of the OS acting as Polly’s LF in this case could come to around 4K + VAT (a large proportion of Polly’s remaining savings). Given this I would question whether or not it is necessarily in Polly’s best interests for the OS to accept the invitation to be her LF for this non-contentious case.If the OS is minded to accept the invitation to become Polly’s LF then I would welcome more information about what the OS could/would do for her in this role and I wonder whether we could think of a strategy to reduce the costs ….”

29th September 2025 It’s the (extended) deadline for the Official Solicitor to let the court (and us) know whether or not she intends to act as Polly’s litigation friend. We receive an email “The Official Solicitor is still considering the court’s invitation to act and hopes the Applicant, Professor Celia Kiztinger [sic] and the Court will bear with her for a further 24 hours while she concludes her position”.

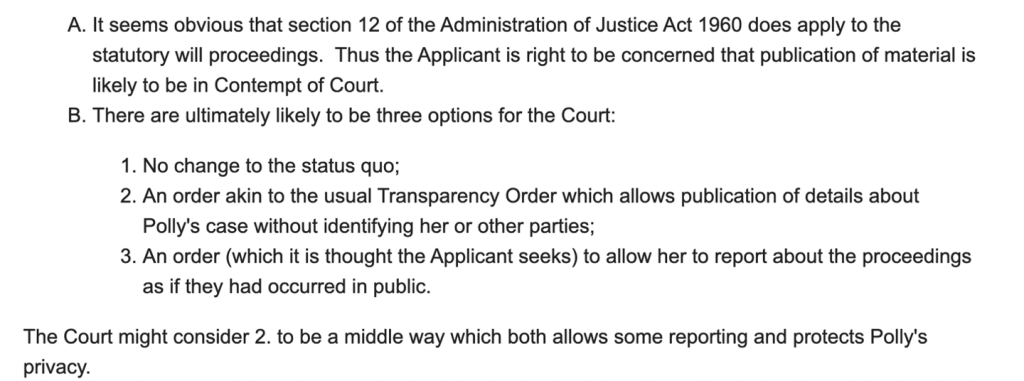

30th September 2025 The Official Solicitor “respectfully declines to accept the Court’s invitation to act as the Official Solicitor’s fees cannot be met by Polly”. Notwithstanding the fact that the Official Solicitor now has no standing to make any particular suggestions on Polly’s behalf, she offers the following (quoted from email from Official Solicitor):

We are surprised by this, since the Official Solicitor normally advocates for P’s “best interests” (as she conceptualises them) and not for a “middle way” between any perceived conflicts of interest[5]. Jenny responded:

As Polly’s sister, and her court-appointed Deputy (H&W and P&F), I confirm that option 3 is the outcome that I believe Polly herself would want – please see my submission on Form COP 5. Given the weight attached to P’s values, wishes, feelings and beliefs (while recognising that they are not determinative), my own assessment is that option 3 is also, for that reason, in her best interests.

I believe Polly would want to enable reporting about the proceedings as if they had occurred in public without reporting restrictions. She would particularly want her family to be able to write about this case in their own names, using her name in whatever we write.

I also note that not one of the parties involved in the case has a problem with this.

I hope that in considering the balance of Article 8 and Article 10 rights, the court will recognise that, in this case, there is no conflict between them, since Polly would wish to exercise both rights by having her family publicly tell her story.

10th November 2025 We receive a sealed court order that says that as of 8th December 2025 we are: “… permitted to identify Polly Kitzinger as a P as defined by The Mental Capacity 2005[6] in respect of whom the statutory will application was made. The Applicant may refer to those persons formally served with this application of 7 June 2025, the judge, the court and information relating to P which was put before the court in private in the statutory will application, save that P’s address shall not be disclosed.” (Order made by DJ Ellington, COP 11757133-04, issued on 10th November 2025). The delay in applying the order was to allow me, as applicant, to serve the order on everyone and to notify Polly of it (that meant all those COP 20A and COP 20B forms again, this time to tell people about the order rather than as previously to tell them about the application). I had to do this by 24th November 2025, and if anyone objected they could apply for a “reconsideration” (on a COP 9 form) within 14 days of receipt of the order.

A recital to the order says that it’s “undesirable” that it’s not been possible to appoint a Litigation Friend for Polly: “The difficulties include that the Official Solicitor requires security for her costs but P’s financial circumstances have changed considerably since the statutory will application. She now meets the financial eligibility for public funding on care and care is publicly funded but the Official Solicitor has not secured public funding of costs through the Legal Aid Board. None of P’s siblings are in a position to act as Litigation Friend as they have an actual or perceived conflict of interest and all consent to the application. The Official Solicitor has assisted the court with some observations” (§8). Nonetheless, given that the applicant (me), Jenny (Polly’s deputy) and Tess are all Polly’s sisters, and as such are persons who are “‘engaged in caring for P or interested in her welfare’ under the terms of sub-section 4(7)(b) of the Act”, and that we all (along with others served with application) support it, the judge was “satisfied that P’s interests and position can be properly secured without being joined to these proceedings and without making any further direction concerning her participation in these proceedings”. The judge noted, in particular, that: “There is no actual or perceived conflict which would warrant dismissing the application because it is the Applicant and Jenny Kitzinger who want to write about the statutory will application. That is inherent in the nature of the application and is appropriately addressed by full consideration of section 4 of the Act.”(§18)

8th December 2025: By 4pm, nobody has sent me any objection to the order or asked for reconsideration. When Tess told Polly about it, Polly gave it a thumbs up. We are now able to write about Jenny’s application for Polly’s statutory will.

9th December 2025: We publish Applying for a statutory will: Observation and personal experience by Jenny Kitzinger.

Mission accomplished!

Celia Kitzinger is co-director of the Open Justice Court of Protection Project. She has observed more than 680 hearings since May 2020 and written more than 100 blog posts. She is on LinkedIn (here), and also on X (@KitzingerCelia) and Bluesky (@kitzingercelia.bsky.social)

[1] There is a ‘general rule’ in the Court of Protection that hearings are to be held in private (Rule 4.1 Court of Protection Rules 2017) – but, in practice, there are very few private hearings. That’s because the Transparency Pilot, launched in 2016 and now incorporated into ordinary practice, “reverses the general position signalled by the Rules” in order to reflect the “well-known case law articulating the principles of open justice and personal privacy: there is now “a supposition in favour of a public hearing”(Lord Justice Jackson in Hinduja v Hinduja [2022] EWCA Civ 1492) with accompanying reporting restrictions

[2] We’ve blogged some such cases, e.g. An emergency statutory will for a dying man; Judge approves statutory will in contested hearing.

[3] For example, we’ve published an essay for Hastings Bioethics Centre about how Polly’s voice was silenced and ignored by the medical decision-making about her, with no consideration of her passionately held values and beliefs about independence, autonomy and freedom and we told Polly’s story to journalists at the BBC (e.g. “Doctors wouldn’t let my sister die”) and to the local press (e.g. https://www.yorkpress.co.uk/news/11027266.york-academic-speaks-of-the-need-for-debate-on-allowing-brain-damaged-people-to-die-with-dignity/; https://www.walesonline.co.uk/news/health/sisters-brain-injured-polly-kitzinger-6511685). We’ve also used Polly’s story to campaign for greater awareness of lawful choices at the end of life, especially for Advance Decisions to Refuse Treatment https://theconversation.com/dying-matters-thats-why-we-must-listen-to-patients-wishes-41843. This would make it virtually impossible to conceal the fact that we were writing about Polly in any report of Court of Protection hearings.

[4] For example: Amanda Hill applied to vary the transparency order so as to be able to identify herself as the daughter of a protected party (I’m finally free to say I’m a family member of a P: Does it have to be so hard to change a Transparency Order? ); Heather Walton applied to vary the transparency order so as to be able to identify herself as the mother of a protected party (A mother now free to tell her Court of Protection story).

[5] The current position of the Official Solicitor in advocating solely for P’s best interests is exemplified in the position she has adopted in relation to disclosure of position statements for observers. The OS has created a template refusal to send (even anonymised) position statements to observers, on the grounds that P probably wouldn’t want observers to have access to “personal” information about them. She declines to send position statements unless ordered to do so by a judge. This is not a “middle way”: it explicitly declines to engage with Article 8/Article 10 balancing, which the OS leaves to the judge. In Polly’s case, we have good evidence that Polly would want (what the OS considers) “private” information published about her, so the logical corollary of the stance the OS displays in relation to position statements (i.e. to act in accordance with P’s presumed wishes) would surely be to offer (3) as being in Polly’s best interests.

[6] The word “Act” is missing in the original.

EXCELLENT FOR SO MANY AND HUMANITY sorry caps on…

I read this case with great, grieving interest, in this legal area which shall, at some time in our lives, impact everyone via self, family or friends.

I highly commend your love and ethical drive for Polly and all humans. It was hard, in places, to read – through tears. Horrific crash.

Kind Regards Siobain-Marie Eaton

On Sun, 18 Jan 2026, 19:19 Promoting Open Justice in the Court of

LikeLike