By Celia Kitzinger, 7th Jan 2020

Open justice. The words express a principle at the heart of our system of justice and vital to the rule of law. …. Open justice lets in the light and allows the public to scrutinise the workings of the law, for better or for worse. (Lord Justice Toulson R (Guardian News and Media Ltd) v City of Westminster Magistrates’ Court [2012] QB 618 )

Since January 2016, the usual approach in the Court of Protection is that attended hearings are in public, with reporting restrictions to protect the identity of P and their family (Practice Direction 4(c)). During the pandemic, with the rapid move to remote justice, the situation has been somewhat different from usual, but the court’s commitment to transparency remains firmly in place.[1]

Despite the fact that most hearings are listed as “in public” or “in open court”, it was until very recently extremely unusual for a member of the public (unconnected with the parties or their advocates) to attend a hearing. Until we launched the Open Justice Court of Protection Project in June 2020, I was often the only ‘public observer’ in court. It also was – and remains – rare to find journalists at hearings – especially in courts outside London, and at hearings before district judges. This means the vast majority of Court of Protection hearings were held “in open court” in name only.

Perhaps because it is a relatively recent development for members of the public to attend hearings, it can still be challenging to gain access. My own experience is that I am admitted to only about one in every three of the court hearings I ask to observe. (This proportion applies equally to hearings listed as ‘public’ and hearings listed as ‘private’: those words in the listings are not reliable guides to whether or not you will gain access).

This post explores how and why the public is so often excluded from Court of Protection hearings. I begin with the ‘inadvertent’ exclusions that (in my experience) constitute the vast majority of cases. I’ll then highlight some ‘deliberate’ exclusions. In particular, I’ll describe how and why members of the public were deliberately excluded from a hearing before Mr Justice Keehan (COP 12803319, 23 December 2020) that I was eventually – and as a special exception – permitted to attend. I will conclude by sharing what I learnt from that experience and considering the implications of my experience for open justice in the Court of Protection.

Inadvertent exclusion

Massively the most common way in which members of the public are excluded from Court of Protection hearings is that there’s simply no response to our requests for access. That’s how my experience with Mr Justice Keehan’s hearing on 23 December 2020 began – as an inadvertent exclusion.

On Tuesday 22nd December 2020 at 18:53, I sent an email to the Royal Courts of Justice (RCJ) asking to observe the hearing before Mr Justice Keehan the following morning. It had been listed on the RCJ website (posted around 16.30 that day) as “For Hearing in Open Court”. The RCJ never replied – not to that email, and not when I resent it the following morning. I was disappointed, but not particularly surprised.

My colleague Adam Tanner – who frequently blogs for the Open Justice Court of Protection Project (e.g. here and here) – was also trying to observe hearings during this same period. He told me:

“In a single two-week period leading up to Christmas I emailed the RCJ about 13 separate hearings that I wished to attend. Eight of those emails went completely unanswered, and one was responded to three hours after the hearing had started.” (Email, 29th December 2020)

I’ve learnt over the course of more than 300 requests to observe hearings that I’m most likely to gain access if I email repeatedly (the night before, again in the morning, again within an hour of the scheduled start of the hearing) and – if a phone number is provided – I follow up with a phone call 40 mins or so before the scheduled time of the hearing. It also seems effective to tweet the fact that I am seeking access to a given hearing, especially if I also tag in @HMCTSgovuk and direct message any barristers or solicitors I happen to know who might conceivably be involved in the case, or who might know someone who is. Obviously, it shouldn’t be necessary to do this, and it’s an uncomfortable strategy to have to adopt. I am undoubtedly inconveniencing busy people, and however politely I try to phrase the emails and tweets, it feels like insistently battering on a locked door to demand entrance. It also requires an investment of time and the determined cultivation of a sense of entitlement not possessed by most health and social care professionals (who constitute the majority of people interested in observing hearings).

In the case of Mr Justice Keehan’s hearing on 23 December 2020, I had another route of access (also not available to most members of the public). I’ve observed his hearings in the past and have his clerk’s contact details. So, at 9.22am, just 38 minutes before the hearing was due to start, having finally given up on getting any response from the RCJ, I emailed her apologetically, explaining the situation, and she replied with an MS Teams link at 9:29am. Success!

By that time, several members of the public – alerted to the hearing by our “Featured Hearings” page – had contacted me to say that they had not received any response to their email to the RCJ and asking whether I could help. Although I passed names and email addresses to the judge’s clerk, other members of the public were not admitted – for reasons I discuss below.

More broadly, I am not sure why members of the public are so often excluded from hearings that are listed as “Open Court” and hope that this is something that the HIVE group will investigate. My impression is that it’s usually because court staff are busy and don’t find time to deal with our requests. As I indicated earlier, it seemed a particular problem in the two weeks before Xmas, but it’s been a more general problem throughout the year. Occasionally I’ve been told, when I’ve phoned, that staff haven’t had time to open their emails. Often the phone rings unanswered or I listen to recorded messages in an endless loop. A few judges have written apologising that I didn’t get access to their hearing because they’d been forwarded my request (sent to the administrative regional hub) too late to action it, or because they were struggling already with joining multiple counsel to conference calls or with uncooperative video-platforms, and couldn’t find time to deal with my request on top of that.

I suspect that some of the requests to which I get no response concern hearings that are adjourned or vacated (i.e. they don’t actually happen, so in reality there’s nothing to be excluded from) – but if so, it’s often the case that nobody tells me, so this is just guesswork. Sometimes I do get responses explaining that a hearing isn’t now happening – and that really helps to dispel the notion that members of the public are being deliberately excluded.

So, in my experience the fundamental principle of open justice often falters and fails without anyone willing it to do so. The Court of Protection is not secretive by design – but it is not adequately designed for transparency.

Deliberate exclusion

Sometimes I’ve been deliberately excluded from Court of Protection hearings.

Occasionally I’ve been told that a case was wrongly listed and should have been ‘private’ all along, so my application to observe it has been refused without further explanation. This includes some Dispute Resolution Hearings, all of which are held in private, but the lists don’t always specify that’s what they are.

One case was redesignated as ‘private’ after my request to observe it – and after I had observed an earlier ‘public’ hearing in the same case. There was no explanation as to why this had been done.

On several occasions recently, I’ve been admitted to video-platforms only to find counsel having a discussion about whether or not to exclude the public and then making representations to the judge: on one such occasion we were permitted to remain (see this blog post about a case before Hayden J); on another occasion (also before Hayden J), we were excluded, with the explanation that P was exceptionally vulnerable.

The Court of Protection Rules 2017 specify that the court can decide not to make a hearing public, or to make only part of a hearing open to the public, or to exclude any persons or class of persons from the hearing, if there is “good reason” for doing so. In making this decision the court will have regard in particular to:

(a) the need to protect P or another person involved in the proceedings;

(b) the nature of the evidence in the proceedings;

(c) whether earlier hearings in the proceedings have taken place in private;

(d) whether the court location where the hearing will be held has facilities appropriate to allowing general public access to the hearing, and whether it would be practicable or proportionate to move to another location or hearing room;

(e) whether there is any risk of disruption to the hearing if there is general public access to it;

(f) whether, if there is good reason for not allowing general public access, there also exists good reason to deny access to duly accredited representatives of news gathering and reporting organisations. (para. 2.5 Practice Direction 4(c))

This provides the basis on which the public can be deliberately excluded, and it turned out these criteria had been invoked to exclude the public from Mr Justice Keehan’s hearing on 23 December 2020.

Why Mr Justice Keehan decided to exclude the public

When I joined the video-platform for the hearing, which had been listed as “for hearing in open court”, there were three barristers online: Ian Brownhill (acting for the applicant local authority), Joseph O’Brien (acting for the Official Solicitor), and Fiona Paterson (acting for the National Probation Service). The issue of the public/private status of the hearing was immediately raised. In discussion before the judge arrived, they recalled that there had been what was described as “an oven ready judgment” made in 2019 excluding members of the public from attending the hearing, but that it had never been handed down. This was subsequently located and sent to me.

Ian Brownhill said that the case had been in front of different judges at different tiers (since 2015 I think) and that over the years different orders had been made. Initially it was open to the public with a reporting restriction in place, but the local authority had subsequently applied for hearings to be in private to protect P’s identity and a previous judge had approved this application.

When the case was allocated to Mr Justice Keehan in 2019, he questioned why the case should not be heard in public, subject to a suitably worded transparency order. The local authority and National Probation Service asserted that the risks to P of hearing the case in public were too great: there would be ‘sensationalist’ reporting and a risk of ‘reprisals against him’. (The local authority also argued that there was a risk of disruption to the hearing from angry members of the public – who might include members of vigilante groups or family members of P’s victims). The Official Solicitor submitted that the public should be admitted, subject to an appropriately worded transparency order that specified what could be reported and that “the court should have confidence that accredited media organisations will report the proceedings in a responsible way”. (She further noted that the argument about disruption was speculative and any disruptive members of the public could be removed from court.)

In his judgment in 2019, Mr Justice Keehan considered that “the need to protect P is a very powerful factor in favour of holding the proceedings in private”. He continued:

16. The importance of public justice, however, is a central tenet of the Court of Protection. It should only be overridden when the circumstances of the case compellingly, and on the basis of cogent evidence, require the proceedings to be heard in private.

17. I accept the submissions of the Official Solicitor that in her experience and that of her office is that [sic] those members of the accredited media who attend Court of Protection proceedings respect the orders of the court and report proceedings in a responsible manner. This mirrors this court’s experience.

18. Accordingly, I am satisfied that if:

i) I exclude members of the public from attending future hearings of these proceedings; but

ii) Permit accredited members of the press and broadcast media to attend; and

iii) I make a transparency order in the terms proposed by the National Probation Service and agreed by the other parties;

the Article 8 rights of P will be protected and the Article 10 rights of the press and broadcast media will be respected.

19. With the exclusion of the public and the making of [an] appropriately drafted transparency order the risks to P of identification, and the consequences of the same, are reduced very considerably. These reduced risks do not justify overriding the central tenet of open justice in the Court of Protection. Accordingly, I do not consider it necessary and proportionate for these proceedings to continue to be heard in private.

Re P (Court of Protection: Transparency) 2019 EWCOP 67

In sum, then, given the particular facts of this case, Mr Justice Keehan had reversed the previous judge’s decision that the hearing should be held in private, permitting journalists to attend (subject to reporting restrictions), but excluding members of the public. This was described by Ian Brownhill (counsel for the local authority) as a “half way house”.

Gaining access to the hearing

Once it became apparent that I had been admitted to a hearing from which members of the public had been excluded by an earlier judgment, the parties were asked address the judge as to whether or not I should be permitted to stay. As they did so, I learnt quite a bit about P.

P is in his twenties and has a “mild learning disability combined with significant deficits in adaptive functioning” including “autistic spectrum disorder” and “attention deficit hyperactivity disorder”. This places him at risk of offending and he has been convicted of several sexual offences and was in prison at the time of the hearing. He is due to be released shortly and the hearing concerned the need to find a suitable placement for him.

The local authority had been concerned because local newspapers had published details about P’s offences, including his name and photographs of him leaving the Crown Court where he was found guilty. They were concerned that he could be targeted by paedophile hunters and vigilantes as a result of this press coverage. They would not necessarily be “people with baseball bats hanging around outside his placement, but could be apparently respectable people seeking to entrap people like him”, said Fiona Paterson.

On the basis of information about P garnered in the first ten minutes (including his first name and the name of the local authority, plus other details not reproduced here), I easily located media reports about P’s sexual offenses. It was also straightforward to find websites of vigilante groups across the UK, such as Dark Justice who impersonate children online to lure people into making inappropriate or sexualised communications with them over the internet, and then provide the material generated by such contact to the police. A large proportion of prosecutions for child sexual abuse result from these ‘sting operations’ and in Sutherland v Her Majesty’s Advocate [2020] UKSC 32 , the UK Supreme Court ruled that prosecutions based on this kind of evidence do not violate the person’s Article 8 right to private life and correspondence.

On behalf of the Probation Service, Fiona Paterson was clearly concerned both (obviously) to ensure that P does not re-offend and also to protect him from becoming the target of online child abuse activist groups (who may themselves commit offences against vulnerable adults, as outlined by the Crown Prosecution Service here).

Anxious that I might be excluded from the hearing, given what I was hearing about the sensitivity of the subject matter, I emailed Brian Farmer, the only journalist who regularly attends Court of Protection hearings and a strong advocate for transparency (check out his blog here) asking if he could attend – and messaged the court to say I had done so. He was on annual leave. Without him, there would be no public report of the hearing if I were to be excluded.

As it turned out, though, none of the parties objected to my presence – albeit without instructions from their clients one way or the other since this situation had not been anticipated[2]. It helped that I have previously observed hearings involving all three advocates (and the judge), have blogged about some of them, and that counsel were aware of my previous reports and considered them “responsible”.

When the judge invited me to address him as to why I wanted to observe the hearing, I made two points. First, that excluding the public (and there has been a recent rash of such exclusions from RCJ cases) risks reinforcing the perception of the “secret court” and so undermining public confidence. Second, that – not yet fully apprised of the facts of this case, but not wanting to cause harm to a vulnerable adult – I was willing to send my proposed blog post to counsel prior to publication and to take advice from them about anything that might harm P and need to be changed[3]. On that basis, I was permitted to remain for the hearing (but there was no further consideration about whether or not to admit other members of the public who had also asked to attend).

The hearing itself: an unsuitable interim placement

On behalf of the applicant local authority, Ian Brownhill provided an exemplary introductory summary of the case. There had been a long history of Court of Protection hearings concerned with P’s capacity and best interests in relation to residence, care, contact and internet use. Throughout this time, there have been repeated problems with placements breaking down (including the specialist provider directly prior to his current custodial sentence, at which he had assaulted staff): he has “been through a vast number of providers”. One feature of P’s behaviour is that, despite the negative consequences to himself (he’s been called “a paedo and a nonce”), he often discloses his offending history and talks about his sexual behaviour and his recent imprisonment was as a direct result of his own disclosures.

The local authority now finds that P is “often rejected by specialist and non-specialist providers” because of this history. He’s due to be released from prison very soon. A long-term placement has been identified but is not yet available because a different local authority has not yet removed a service user (who has given notice) from what will become P’s room. Until they do so, there is no approved placement for P on his release.

Acknowledging that “it’s not the ideal option”, counsel on behalf of the local authority proposed placing P, temporarily, in a room in a well-known (family-friendly) hotel chain, with carers in place during the day (but not at night). P would be electronically tagged and “if it proved problematic this would be reviewed”.

The Official Solicitor’s position was uncompromising: this proposal is “fundamentally flawed” and “exposes my client to the risk of serious harm”. The notion that P would stay tucked up in bed during the night while his carers were absent (simply because he is subject to a curfew) was “based in the world of fantasy”. Counsel pointed out that the court had no way of knowing who else would be staying at the hotel, where exactly in the hotel his room would be, what the staff would be told, or any number of relevant details related both to protecting P and to protecting the public.

The Mental Capacity Act 2005 cannot be used to impose restrictions on someone to stop them from offending. As Ian Brownhill has said in a blog:

“The most that can be said, is that restrictions can be imposed if it is determined that they are in P’s best interests; that best interests analysis could include an aim to keep P out of the criminal justice system.” (Ian Brownhill, blogging here about “the myths and mistakes of capacity and criminality”)

As a consequence, the focus of the argument in court was very much on the harm caused to P by being left unsupervised in a hotel, rather than the harm that members of the public might suffer as a consequence (leaving me feeling somewhat uncomfortable). However, as counsel for the Official Solicitor pointed out:

“P’s welfare is linked with the welfare of the public – they are conjoined here. He remains at significant risk of harm if the proposal for a hotel placement is followed through. If this plan is not reformulated with a more robust package of care by next Thursday, then it will be back on the list. … I hope the local authority heed our concerns. I sincerely hope we don’t see you next week, but I fear that we will.” (Joseph O’Brien, Counsel for the Official Solicitor).

The judge responded immediately in no uncertain terms:

“I agree with absolutely everything you’ve said. I do not doubt the local authority are doing absolutely everything that you can – and no doubt working in very unusual circumstances. But I’m afraid that the proposed plan of the hotel simply will not do.” (Mr Justice Keehan)

On behalf of the National Probation Service, Fiona Paterson reported that she was content with the proposed permanent placement, and she understood that the local authority was “trying to pull out all the stops” to enable P to move there as soon as possible. She had been informed that P’s tag will not sound an alarm if he leaves the hotel “its function is purely historic: so that the police would be able to work out where he’d gone [say at] 2am when they interrogated the system the next morning.” She hoped very much that P would not have to go to the hotel, but if he did end up going there, she had a number of pragmatic suggestions, including that he be brought to the probation service offices every day, the number of hours his carers are with him was increased, and that the local police were asked to spot check whether he was complying with his nightly curfew – although that would entail relying on the good will of officers.

For me as a public observer, this seemed a completely ghastly situation: both the safety of P and the safety of the public would self-evidently be compromised by placing P in a hotel with insufficient surveillance in place. “It’s not unreasonable to assume that having just been released from custody, he is at the greatest possible risk”, said the judge. Nonetheless, following Fiona Paterson’s submission, and her suggestions for addressing issues that might arise in a hotel placement, he did seem more open to entertaining the possibility that this stop-gap solution might need to be adopted.

Addressing counsel for the local authority, the judge said that he expected the situation to be addressed by “someone who is, shall we say, at the top of the food chain”. The focus of the local authority “has to be to deal with the other local authority to move that service user out so that P can be admitted. If it has to be the hotel, then you need to be looking at more hours of care.”

In what sounded to me like a thinly veiled warning, he added:

“In due course I might find myself making another judgment, explaining why P was placed in a hotel and why something unfortunate happened to him or to a member of the public, and referring to the public body responsible for that state of affairs coming about.” (Mr Justice Keehan)

Reflections

Open justice is not incompatible with the occasional deliberate exclusion of members of the public – but these exclusions need to be clearly exceptional and well-justified if they are not to risk undermining the principle of transparency. “The need to be vigilant arises from the natural tendency for the general principle to be eroded and for exceptions to grow by accretion as the exceptions are applied by analogy to existing cases.” (Lord Woolf in R v Legal Aid Board, ex p Kaim Todner [1999] QB 966).

I’ve attended several hearings where P has been involved in criminal behaviours (including ‘upskirting’, sexual harassment, sexual assault, substance abuse, and drug-dealing) and we’ve blogged about two previous cases where P was in prison at the time of the hearing (here and here) – both, like this one, applications for judicial decisions about where he should be placed on release. I’ve also observed hearings where P has been the victim of crime – including rape, coercive control, and ‘cuckooing’ (in which drug dealers use the home of a vulnerable person as a base for drug trafficking). In at least two of the latter cases, the judge warned that P needed protection from perpetrators who were either still at large, or who might seek P out for retaliation. All these hearings were held in public with stringent reporting restrictions in place. Reflecting on the threshold for making a hearing ‘private’ rather than ‘public’, it’s not immediately obvious to me why this case, in particular, should exclude members of the public (excepting me) and not these other hearings I’ve observed. It is perhaps accounted for by the sheer visceral rage that child sexual abuse can occasion and by the existence of organised groups who’ve made (I discovered) threats of physical violence against P (by name) on public websites.

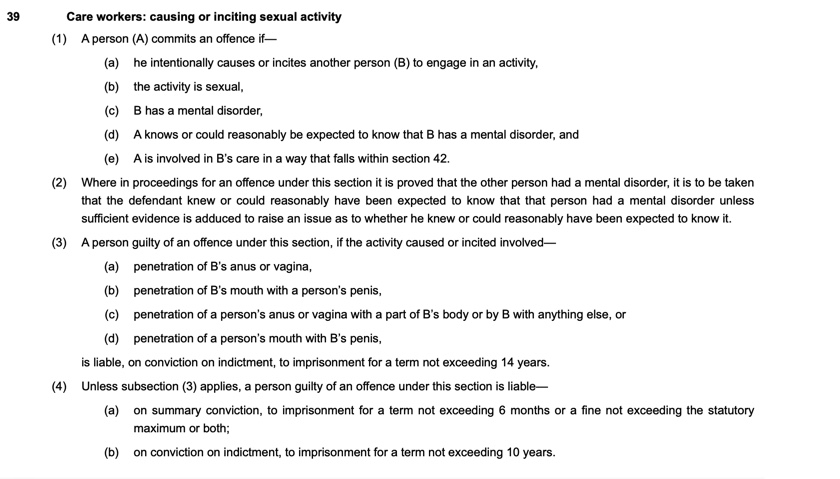

Simply the fact that P is vulnerable and sensitive personal details are being discussed in court is clearly not sufficient reason to exclude the public, since that would pretty much prevent open justice altogether in the Court of Protection. We often bear witness to intimate personal details about vulnerable Ps – because these intimate behaviours have become the object of judicial decision-making. That is of course the point of open justice in a democratic society. If the long arm of the state is to reach down into our personal lives and determine, for example, whether or not we can have sex – ever, at all, with anyone (as here), or engage in the sexual practice of our choice (as here), or use a sex worker (as here) – then those decisions, and the processes by which they are made, need to be transparent. Any of us – or our friends and relatives – could lose capacity to make important decisions for ourselves in the future and many observers work with people in that situation. When we observe how lawyers argue and judges decide on such matters we learn about how the law works in practice. This enables us to understand the laws by which we are governed, to use them to protect ourselves against future loss of capacity, to better employ them in the course of our work, and to develop informed critiques of them and campaign for change if we believe them to be wrong. The idea that major decisions about people’s intimate lives – affecting fundamental human rights – should be made by the state in secret without public oversight is something I find abhorrent and quite terrifying.

Engagement with the concrete particularities of specific cases can also graphically display the fault-lines in health and social care services. One of the values for me in being allowed to observe this case was that it was driven home to me the extent to which adult social care is on its knees. The fact that the local authority was contemplating placing P (this P of all Ps) in a hotel illustrates how dire the situation is – and I know from observing other hearings the extent to which there is a wider problem with finding appropriate placements: Ps are regularly placed in accommodation described as “manifestly inappropriate” because there is nothing else available (see the blogs by Beverley Clough here; Caroline Hanman here; and NB here). Settled case law establishes that the court is limited to making a decision about what is in a person’s best interests by choosing between available options: it cannot compel a local authority to add new placements or care packages to those on offer (N v ACCG [2017] UKSC 22). In practice, this often means a constrained choice between unsatisfactory options – or, as in this case (so far), no choice at all. The long-term solution can only be better funding and reforming adult social care.

Does a hearing that excludes the public militate against open justice and harm the reputation of the court?

Over the past six months I’ve worked extensively with members of the public seeking to observe Court of Protection hearings. The vast majority are either health and social care professionals, or aspiring lawyers. Their intention in observing a hearing is to gain valuable continuing professional development (CPD) and the blogs on our website bear testimony to the rich learning experiences so gained.

What militates most against open justice and harms the reputation of the court is the routine, mundane, inadvertent exclusion of members of the public. Not replying to emails, and leaving phones ringing unanswered sends the (no doubt unintentional) message that members of the public are not considered important, that open justice simply doesn’t matter to the court, and that those asking to observe hearings can casually be ignored. These health and social care professionals (like court staff, lawyers and judges) are busy professionals who are often carving out CPD time in their days off, or during their annual leave. It takes time and research – and sometimes courage! – to identify a hearing in the time slot available and email the court. It’s disappointing and disheartening not to receive a reply. Some blame themselves for having somehow asked ‘incorrectly’. Others – especially after repeated failed attempts – wonder if there isn’t actually a conspiracy to exclude them. If nothing else, the court comes to feel a disorganised and unwelcoming place.

Having observed the hearing before Mr Justice Keehan, I understand better why parties might be reassured by hearings conducted in private – or at least without members of the public in attendance. I learnt a lot from observing this hearing and ironically it has bolstered my faith in the court’s commitment to open justice. I think most members of the public could understand and accept being deliberately excluded from attending a small minority of hearings – especially if they were clearly flagged up as “definitely private” on the relevant lists (and somehow distinguished from all the ‘not really private’ ones currently appearing in the lists during the public health emergency – see Footnote 1). In my experience, observers are very aware of and sometimes chastened by the intimate details they learn about P: they sometimes describe feeling “intrusive” or “voyeuristic” (Caroline Barry’s words here) and would be sympathetic to decisions to exclude them so as not to expose P to their observations when the risk of harm is particularly acute. In general, the public are not clamouring for access to particular specified hearings so much as simply trying to observe a hearing – any hearing! – in the particular time slot they’ve designated for CPD. Often the hearings they most want to observe are those dealing with issues that are part of their everyday working lives (e.g. Deprivation of Liberty Orders, s. 21A applications) rather than the more ‘sensationalist’ issues they are less likely to encounter themselves.

What’s needed is a solution to inadvertent exclusion: this is what really damages the reputation of the court. Fixing administrative problems associated with admitting the public to Court of Protection hearings (ensuring that emails are forwarded to judges and answered in a timely fashion) is less intellectually engaging than discussing the balance between competing Article 8 and Article 10 rights or reworking the standard transparency order to cover all possible identifying information in complex cases with distinctive fact patterns – but I think it’s the way forward for the court in pursuit of transparency and open justice.

Celia Kitzinger is co-director (with Gill Loomes-Quinn) of the Open Justice Court of Protection Project. She tweets @kitzingercelia

Photo by Matt Seymour on Unsplash

[1] With the move from physical courtrooms to audio- and video-platforms, Practice Direction 4C and any transparency orders previously issued in accordance with were disapplied. It can be re-applied (and the transparency order reissued) if any member of the public (or journalist) requests access – so ‘private’ doesn’t really signal an intention to exclude us. I am rarely refused access to hearings listed as “private” and they constitute around 25% of the 123 hearings I have so far observed. You can see the new template (which lists hearings as ‘private’ by default) as an appendix (p. 18 onwards) to the 31 March 2020 Guidance here. Notice that it specifically allows for “ongoing consideration” being given to “the means by which any remote hearing can be accessible to the public”.

[2] The transparency order (sent to me on 30 December 2020) now reads: “Subject to further order of the Court, that any attended hearings of this application are to be in private but that accredited members of the Press Association and Professor Celia Kitzinger of the Open Justice Court of Protection Project are permitted to attend for the purpose of reporting upon these proceedings, subject to the terms of this amended transparency order.”

[3] Thank you to counsel for taking the time to read and make suggested amendments to my blog. I have incorporated all their suggestions. There was no suggestion that I had written anything that could lead to the identification of P. The majority of suggested amendments were typos. The others were clarifications of points that I had reported incorrectly: I can see (in retrospect) that the wording of certain points made in court was open to misinterpretation by an observer who did not have access to documents (such as the care plan) to which counsel were referring. For example, in my original version I implied that Fiona Paterson’s suggestion was that probation officers would visit P in the hotel, but actually it was thought that P might be taken to the probation service offices. And the reference to ‘pulling out all the stops’ was apparently to attempts to ensure that P could gain access to his permanent placement, where I had incorrectly written in my draft post that it referred to efforts to find an alternative interim placement. It was useful to me as an observer to receive feedback about errors of reporting. For the avoidance of doubt, as lawyers say, there was absolutely no question of ‘censorship’ whatsoever.