By Rhiannon Snaith, 30th August 2023

An evangelical preacher in his fifties (KT) had a stroke in February 2022. He underwent emergency surgery but has sustained significant brain damage and never regained consciousness. He is currently in hospital, in a coma and also has end-stage kidney failure and Type 2 diabetes.

The Trust was seeking a declaration that KT lacks capacity to make his own decisions about treatment and approval of an Order permitting withdrawal of life-sustaining treatment, specifically dialysis and clinically assisted nutrition and hydration (CANH). His life expectancy if these treatments are continued is likely to be 6-9 months, and death could be sudden, and possibly without his family present. Without the treatments, he will die a managed and predictable death within a couple of weeks. The family position is that it is in KT’s best interests to continue receiving treatment. The Official Solicitor, acting on behalf of KT, reserved her position until the closing statements at the end of the hearing.

KT’s wishes, beliefs and values were important factors that were considered throughout, along with their place in best interests decision-making. Right at the beginning of the hearing, Mr Justice Hayden said:

“Mr T has practised in a proselytizing way as a pastor in a very robust, muscular, and uncompromising version of Christianity, and his has been uncompromising. The concept of faith being able to move mountains is not figurative for him. It is real. He believes very absolutely in the power of prayer. And that may lead me to the conclusion that, invidious though his situation is, he would have preferred it to the alternative. Much of the evidence points to that. If I do come to that conclusion, how do I address best interests?”[1]

The question of what KT would want for himself in this situation was difficult to determine. KT’s family did not have discussions with KT about what he would want in this situation but strongly believe that if KT had the capacity to choose, he would want treatment to be continued. The Trust argued that there is not sufficient evidence of what he would want.

This case (COP 14075103) before Mr Justice Hayden was heard in the Royal Courts of Justice over two days (Tuesday 22nd of August 2023 and Wednesday 23rd August 2023). It was listed as ‘hybrid’ which meant that people could attend either in-person in the courtroom or (as I did) remotely using a video link.

The applicant in this hearing was the Trust, represented by Vikram Sachdeva KC.

The person at the centre of the case (KT), the first respondent, was represented by Fiona Paterson KC via the Official Solicitor.

KT’s wife was the second respondent (as a litigant in person) and his sister (GT), whose views are aligned with the rest of KT’s family, was third respondent, represented by Francesca Gardner.

Witnesses called for the Trust were: Dr D a Consultant Nephrologist, Dr W a Consultant in Neurorehabilitation,Dr B a Consultant Neurosurgeon, and independent expert Professor Derick Wade. Witnesses were also called for the family.

DAY ONE

Witness 1 – Dr D, Consultant Nephrologist

I joined the hearing slightly late (due to technical difficulties my end) as Dr D was giving evidence to the court. KT had been diagnosed with end-stage kidney failure in 2015 – meaning that his kidneys were providing less than 15% of their normal level of function. In end-stage kidney failure, the body is no longer able to survive without treatment to remove waste products (kidney dialysis), which he has been receiving since then. Dr D was explaining the burden dialysis has on patients’ quality of life, stating that treatment can often lead to patients experiencing cramps, feeling sick, fatigued or like they may pass out (although others cope reasonably well). It was described as a “burdensome” treatment.

Dr D said that KT is usually sat upright in a hospital bed and that dialysis comes to him three times a week so that he does not have to be moved to another location.

Mr Sachdeva, counsel for the Trust, questioned Dr D as to why KT was no longer on the kidney transplant waiting list despite having kidney failure. Dr D explained that KT used to be on the list and was scheduled to have a transplant, but it never happened for “various reasons”. She further stated that when KT suffered a brain haemorrhage, he was taken off the list due to the increase in risk. They were not sure he would survive being put under anaesthesia and Dr D stated that there was an “unacceptable increase of risk” due to the medication KT would need to be on to have the transplant. Mr Sachdeva asked: “So, a transplant is not an option?”, to which Dr D replied “exactly”.

It was explained by Mr Sachdeva that in the written statements submitted to the court the doctors gave the average life expectancy for someone who has kidney failure, diabetes and is on dialysis as 3-5 years. KT has survived 6 years on dialysis so far. At this point, the judge intervened and asked why KT has lived longer than anticipated, Dr D replied that it was “hard to know for sure” but that it sounded as though KT was a “motivated”patient before suffering a brain haemorrhage and knew what to do to stay well. He also managed his own dialysis.

Should treatment continue for KT, Dr D said that while cardiac arrest could be a cause of death, “infection is also a risk, particularly because he [KT] is bed bound, therefore he is at risk of pneumonia and pressure sores and the things that will ensue from that leading to sepsis”. Dr D explained that KT’s tracheostomy, PEG (Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy) and cerebral spinal fluid shunt could all be portals for infection. She went on to explain that for patients who require long-term dialysis “their access point for the blood stream is one of the key determinants of their prognosis”.

Dr D explained that there were two ways to access the bloodstream for haemodialysis. The first, as is the case for KT, is with an AV fistula which is a blood vessel located in the arm, this method offers “a low risk of bloodstream infection”. However, some patients who have diabetes and need dialysis are unable to have a fistula in their arm, so they need a piece of plastic tube in the vein from which there is a “high risk of it becoming infected”. Dr D states that KT’s fistula “continues to work very well”, so there is currently “no increased risk in bloodstream infections”.

The judge questioned whether “the most likely circumstances in which he [KT] might die would be cardiac arrest, or sepsis or fluid overload”.

Dr D explains that “if we [treating team] can’t remove the fluid if the blood pressure keeps dropping, that would be what would lead to the fluid overload”. She further stated that “in KT’s case, sepsis is unlikely to occur from the fistular” but if it stopped working then they would have to put a tube in the vein which would result in a higher risk of sepsis. Dr D went on to clarify that “the risk of hospital acquired pneumonia remains…which could lead to sepsis which could prove fatal”.

Mr Sachdeva asked why KT’s would not now be a candidate for dialysis were it not that he’d already been receiving it before his stroke. Dr D explained that “it’s really because of the lack of evidence of any benefit in terms of survival and quality of life in this situation”. Although, she said that it was “impossible” to comment on KT’s quality of life because “I don’t know how much he is aware of”. Reading the evidence submitted by (I think) Professor Wade, Mr Sachdeva said “a good death is possible…only through careful planning and avoidance of distress”. Dr D agreed.

Dr D said that KT’s clinical situation has become worse explaining that in the first few months of KT’s admission they reduced his blood pressure tablets before eventually stopping them, and that KT got to a point where he was “tolerating dialysis”. However, KT then started experiencing drops in blood pressure during dialysis despite there being no change in the process. Dr D stated that his heart muscle had weakened which was a concern. In the statement submitted to the court it was stated that KT’s blood pressure dropped “in 9 out of 36 occasions” during dialysis. His low blood pressure could cause a heart attack, further brain injury and cardiac arrest.

Dr D explained to the court that if KT’s blood pressure continued to go down then they “would sometimes have to give fluid back into the vein” to bring his blood pressure back up, but in doing so they are “going several steps backward” as KT needs fluid removed. So, having to give fluid back could make the situation worse and may lead to fluid overload.

It was clarified by Mr Sachdeva that according to the written evidence, fluid removal was reduced as KT’s blood pressure dropped too low with it being 55 over 38. Dr D explained that “many people would not be conscious with a blood pressure of 55 over 38” and that for most people this would lead to unconsciousness and could “lead to heart attack or heart rhythm disturbance”. It was described as life threatening.

Dr D said: “Sadly, I do believe that his [KT’s] death is inevitable, and there is a risk it could happen in a sudden and uncontrolled way”. She explained that she wanted to avoid causing “unnecessary suffering” for KT and his family but said that she also respects their wishes and beliefs.

When asked by the Official Solicitor to describe the level of risk to infection in the coming months, Dr D stated that in the Autumn months there was an “increase in cases of seasonal flu and it’s quite likely cases of COVID would also increase”. She said that infection could be brought in from numerous sources including other patients, visitors, and staff members so the risk will increase over the autumn and winter months. However, Dr D stated that the risk of infection from the PEG tube or cerebral spinal fluid shunt is always a risk regardless of the season. She also said that the risk of hospital-acquired pneumonia will remain. However, if KT became ill with influenza or COVID there would be an increased risk of him developing bacterial pneumonia, from which the outlook would be poor.

Dr D stated that sometimes patients can deteriorate rapidly with sepsis which can be scary. The judge intervened and questioned, “without wishing to distress the family, why is sepsis such a particularly difficult death?”.

Dr D responded that if someone has pneumonia and they’re producing sputum and are short of breath or feel like they can’t breathe it is “one of the most profound ways to suffer I would say”. Dr D said that no one knows how aware KT is, but with the tracheostomy there are increased problems with coughing up sputum which must be sucked out using special catheters. She said this was not a pleasant situation and is “not something any of us would ever want to have to go through”.

The judge responded saying “sometimes, I have heard it be described as being like drowning” – to which Dr D said “yes, I have heard it described that way too”.

When asked by the Official Solicitor about KT’s risk of developing pressures sores, since he is largely confined to his bed, Dr D says that “he [KT] has been very well cared for by doctors and nurses, and he has not yet suffered from a pressure sore, but the risk remains”.

Witness 2 – Dr B, Consultant Neurosurgeon

Dr B was on call when KT suffered his brain haemorrhage and took him to surgery, which he assisted in. When questioned by Mr Sachdeva as to why KT had suffered brain bleeds, Dr B explained that brain haemorrhages can happen for a number of reasons but for those with cardiovascular disease the risk of having a brain haemorrhage is much higher.

Dr B had prepared two statements that were submitted to the court in which he had stated that there had been no significant clinical improvement in KT’s neurological state. In his statements he had said that KT’s “condition has plateaued”. When asked whether his opinion today differs, Dr B responded “no, it remains the same from a neurological perspective”.

Mr Sachdeva sought to clarify that there was no neurosurgical intervention that could help KT nor any ongoing neurosurgical role that could benefit. Dr B stated that this was “correct” and that KT “has been stable from a neurosurgical standpoint for a long time”.

It was made clear that Dr B did not believe that continuing life sustaining treatment would be in KT’s best interests. Dr B stated “I agree with evidence [Dr D] has given that we can’t change the overall outcome for P” in that KT’s death is inevitable and the only thing that could be controlled is how he dies. Dr B said, “if we continue with current treatment his [KT’s] death with be unpredictable and could cause suffering to him and his family”.

Witness 3– Dr W Consultant in Neurorehabilitation

In her witness statement (read out in court), Dr W said: “It is the opinion of myself and the clinical team that neurorehabilitation is not appropriate. [KT] has no meaningful interactions which could be formulated into a rehabilitation plan”.

It was Dr W’s opinion and that of her colleagues – and the independent expert Professor Wade – that KT is in a prolonged disorder of consciousness (PDoC). She stated that there was “no evidence of awareness” and that KT had only “limited responsiveness”, most of which was clearly reflexive.

According to the written evidence provided by Dr W, it was her knowledge and that of the treating team, that KT had not discussed his preferences regarding what he would want in his current situation. It was also stated that were no documents that contained KT’s views.

Dr W told the court that “there is no prospect of recovery” for KT. She confirmed that the clinical team was “unanimous” in their view that it would “not be in [KT’s] best interests to continue treatment”.

The court was told that KT presents as being in a coma. Dr W said that “it is a deterioration of his clinical state”that his episodes of eye-opening are less frequent. She also said that KT’s brain stem dysfunction is deteriorating which is evident by his disordered breathing pattern. Dr W confirmed that there were “no further neurosurgical interventions that can help him”.

When questioned by the judge whether she believed that it would not be in KT’s best interests for treatment to continue, Dr W answered “yes, that is correct”.

The judge then asked: “If I concluded that KT wanted what most of us wouldn’t want and would prefer to take his chances with a bad death because he believes that to be God’s gift and nobody else’s, would it be in his best interests to go against those wishes?”

Dr W responded that it was a “very difficult question to answer, which is why it has taken so long to get to this stage”. She explained that in KT’s situation “unlike other patients I have been involved with who have prolonged disorders of consciousness and a tracheostomy, the burdens of continuing treatment are far higher, and I am referring to him needing dialysis three times a week. If he were not in hospital, he would need an ambulance three times a week…and because of his diabetes he has increased risk of infections”. She added that the risk of pressure sores mentioned earlier would also be an issue.

Dr W was then questioned by Francesca Gardner, counsel for the family. Ms Gardner began by emphasising that the family are “very grateful for the care [KT] has received and are complimentary of it”. She stated that it was important to them that Dr W was aware of that. The area of disagreement in this case stemmed from whether KT’s treatment should be withdrawn or continued. Dr W stated that she was aware of these facts.

Ms Gardner asked whether Dr W was aware that the family believe that KT has some awareness of them. Dr W answered yes. She said that there was a “remote chance” that the family would be able to identify certain behaviours or mannerisms indicating conscious awareness that a clinician would not be able to.

Dr W was then asked whether she had spent much time with KT when his relatives were also present. She responded “no, I have not”, but explained that she had been with KT when his wife (JO) was there. She said that KT was not based on her ward, so she only tended to see him when there was a specific need.

Ms Gardner questioned whether Dr W had watched the recordings submitted by the family that showed (they believed) that KT was showing signs of awareness. Dr W responded that she had. Ms Gardner referred to a specific entry where a Chaplain (KT receives prayers twice a week) had reported KT opening his eyes and looking at him as he read to him, which was of particular concern to the family. Dr W responded saying that when KT’s eyes are open they tend to move to his left – but this does not indicate a localising response. The configuration of KT’s room, with his dialysis machine on the right of the bed, means that visitors sit on the left-hand side, so it appears that he is looking at them. She said: “the entry by the chaplain is an interpretation of what he has seen… I cannot say whether it was a meaningful response as I was not present at the time”.

Ms Gardner then asked Dr W whether she had treated a patient with a similar prognosis and awareness to KT where she has concluded that it would be in their best interests for treatment to continue. Dr W answered that she had not been involved in a case previously where the patient had severe kidney failure, as KT does, but has had patients whose life expectancy was short and concluded nonetheless that continuing CANH would be in their best interests.

After being questioned about how she had weighed in KT’s religious beliefs and his family’s views into her decision, Dr W stated that “the views are not purely my own, I express them on behalf of the treating clinical team, and I share their view. We tried hard to explore the views of the family…the dilemma was that [KT] had not expressed explicit views about being in this type of situation, which made it difficult”. She explained, “prior to his brain injury, he may have had discussions but there was no evidence of that… the decision is difficult, which is why we are here today”.

If treatment were to continue, Dr W stated that KT “would remain in hospital for the rest of his life”. Counsel for the Trust asked whether, if treatment were withdrawn, she would object to a time allowance to enable KT’s family who live abroad to come to the UK. Dr W said, “I wouldn’t, but I’m not his treating consultant – it would be up to the treating team”.

It was at this point that KT’s wife JO (second respondent) and KT’s sister GT (third respondent) were given the opportunity to ask questions. Through the video link, KT’s wife JO (I think) stated that she first would like to express her appreciation towards the ward, saying that the “staff are great”. To Dr W she said, “You talked about [KT] and said he is in a vegetative state which means he can’t respond to things”. She goes on to explain that KT has a tube that causes “irritation” and says that KT tends to try and pull it out. GT asked, “what do you say about that?”

Dr W responded, “If he has involuntary movement, then he can dislodge it that way or they can catch when he is being repositioned or cared for, but I am not aware of him trying to dislodge his tracheostomy or PEG tube”.

In her written evidence, Dr W described that she had observed KT as having an abnormal breathing pattern in which he had periods of rapid breathing, followed by a period where he was not taking a breath followed by more rapid breaths. Dr W indicated that this was a poor prognostic sign and was due to central apnoea which is indicative of additional brain stem dysfunction. Dr W explained that she was with KT for “20 minutes” to establish a pattern in his breathing. When questioned by the Official Solicitor, Fiona Paterson, whether that was a sufficient period of time to establish a pattern, not just an observation, Dr W said that yes, it was.

Dr W was further questioned by Ms Paterson, as to why KT’s deteriorating brain stem function was a poor prognostic indicator. Dr W said that it was because KT “in this situation can suddenly stop breathing”. KT’s current breathing pattern could result in further injury as the brain is not getting enough oxygen.

When asked by Ms Paterson if KT’s functionality was deteriorating, Dr W said, “it appears so, yes”. She further stated that KT already has brain stem damage which has resulted in a swallowing impairment. Dr W was then asked whether there was a link between brain stem dysfunction and awareness to which she responded, “patients can have severe brain stem dysfunction and be aware”.

The judge intervened and asked Dr W whether KT would be more vulnerable if he acquired a hospital generated infection, as he already has difficulty swallowing. Dr W said that KT had already been on antibiotics for an assumed respiratory infection and that “he appears to have responded to intravenous antibiotics”. However, she did not know entirely how he has responded as she does not work on the same ward that KT is currently in.

Witness 4 – Professor Derick Wade, Consultant in Neurological Rehabilitation, independent expert witness

Following a lunch break, the independent expert witness, Professor Derick Wade, gave evidence. “I have seen a large number of patients with a prolonged disorder of consciousness”, he said, “and he [KT] is among the 2 or 3 at the most extreme lower end of that spectrum”.

In his written reports submitted to the court, Professor Wade explained that according to early observations of KT, there was some indication that he showed low levels of awareness that included responses to oral commands. However, Professor Wade thinks that these are improbable. Observations made in more recent months had not included any suggestion of awareness on a significant level. According to Professor Wade, KT’s level of awareness is “minimal” and “transient”.

In terms of categorising KT in either a vegetative state or a minimally conscious state, Professor Wade stated that there were “no unique signs that will put someone into one state or the other” and believes that it is not necessary to do so as it would not impact “treatability or prognosis”. So, categorising a patient in these terms would not be helpful. However, when later asked whether KT could be classified as being in a coma, Professor Wade said, “yes, as far as the criteria, he can be classified as being in that group”.

The judge then said that while the family agree that there were not behaviours indicating a specific emotional state, they said that he “occasionally showed behaviours which, if he had a greater degree of consciousness, would automatically be suggestive of discomfort or pain”. Referring to one of the passages, the judge said that KT was said to have been “grinding his teeth”. He asked whether that is what Professor Wade had been referring to in his written report, which explained that some behaviours are suggestive of pain or discomfort and that if KT were to experience anything, it would most likely be pain, discomfort, or fatigue. Professor Wade answered “grinding teeth is a behaviour that would be more likely to suggest pain, discomfort or distress”. However, he later stated, “I think it is extremely unlikely that there is any experience [for KT]”.

Professor Wade was asked by Mr Sachdeva about the multidisciplinary report that recorded the results of the WHIM test (a test that assesses and monitors the recovery of cognitive function after severe head injury). The test showed that grinding teeth had been observed 6 out of 9 times for KT. Professor Wade said the “only comment I would make of that is that I cannot say that it means he has pain; it may have no meaning and is just something he does, but if it does have meaning then it would be indicative of pain”. He went on to explain that grinding teeth is common for those with brain damage, though he does not know why. It was also noted that there were no records of KT showing behaviours that were suggestive of pleasure or happiness.

Professor Wade clarified that when he states in his reports that a behaviour is suggestive of pain, “I’m not saying that [KT] is experiencing pain, but that he is showing a behaviour that suggests pain”.

In his written report, Professor Wade stated that being immobile is also uncomfortable for patients and reported that most patients with spasticity report discomfort and pain. When questioned by Mr Sachdeva whether he was implying that KT had spasticity, Professor Wade said, “yes, to an extent. I am just making the point that for someone in his [KT’s] clinical state, overall being immobile is uncomfortable”.

Professor Wade stated that it was “extremely difficult to know” whether someone who is almost completely unresponsive and has no awareness, as he believes is KT’s case, was experiencing pain. He said, “I do not think he has any experience, but those in prolonged disorders of consciousness will respond to external factors like cold or pain or warmth but that doesn’t necessarily mean he has experience…I do not know what is going on inside [KT]”.

In his written report, Professor Wade stated that KT “has deteriorated clinically over the last few months, coinciding with an increase in cerebral atrophy… [KT] will never have autonomy or live outside a hospital environment”. Mr Sachdeva questioned whether this includes nursing homes, to which he responded that yes it did and that he meant any medical or clinical environment.

In terms of the prospect of continuing treatment for KT, Professor Wade believed that it would offer no benefit to him. “I do not think he is consciously experiencing anything, but one has to acknowledge that in the end for someone who is completely unresponsive, we don’t know what he’s experiencing”. Further stating that if KT was experiencing anything it would be an unpleasant experience that he is having, he said “I cannot identify any benefits other than the prolongation of life”.

The judge intervened and stated that the points discussed by Professor Wade are extremely complex both morally and ethically but said that “there comes a point where the aspiration to prolong life is overtaken by the equally strong moral imperative not to protract death”.

Professor Wade said that “when it comes down to [KT’s] best interests, I am not satisfied that he would want to continue in this particular state”. He made the point that there was no evidence of what KT had previously discussed with his family. He further stated that KT was “someone who is concerned about other people…I think he would want to take into account the effect of his continued living on the care team, for example, who have to continue suctioning him when he looks like he’s in pain, and he likely would be – as it is an unpleasant process”.

Ms Gardner, Counsel for the family, asked Professor Wade about the medical records that he had viewed. She stated that he had considered those records but “took the opinion that you did not need to see [KT] again. The family are concerned that it has been 8 months since you’ve seen [KT]” and that there are recordings of his awareness and of KT being awake. She asked what Professor Wade would say to that. He responded that “if I came up to see him, I may be there for two to three hours, not days…even if there were episodes, it is statistically unlikely that I would arrive when one of those episodes arises”. He said that he had to consider his efforts and the efforts of those involved.

When asked by Ms Gardner whether the evidence provided by the chaplain made him want to visit KT, Professor Wade said, “I think that in the end what the chaplain wrote does not constitute in my view an observation independent of interpretation”. He stated that KT is “not totally immobile” and that an interpretation could have been made based on the chaplain’s belief or could have been a human interpretation of the movement. “Awareness isn’t something that will restrict itself to certain circumstances”; others would have also seen it.

Professor Wade explained that KT “has cerebral atrophy, but he is also atrophying” as there are several factors that are causing damage to his brain including low blood pressure and diabetes. He is “deteriorating”.

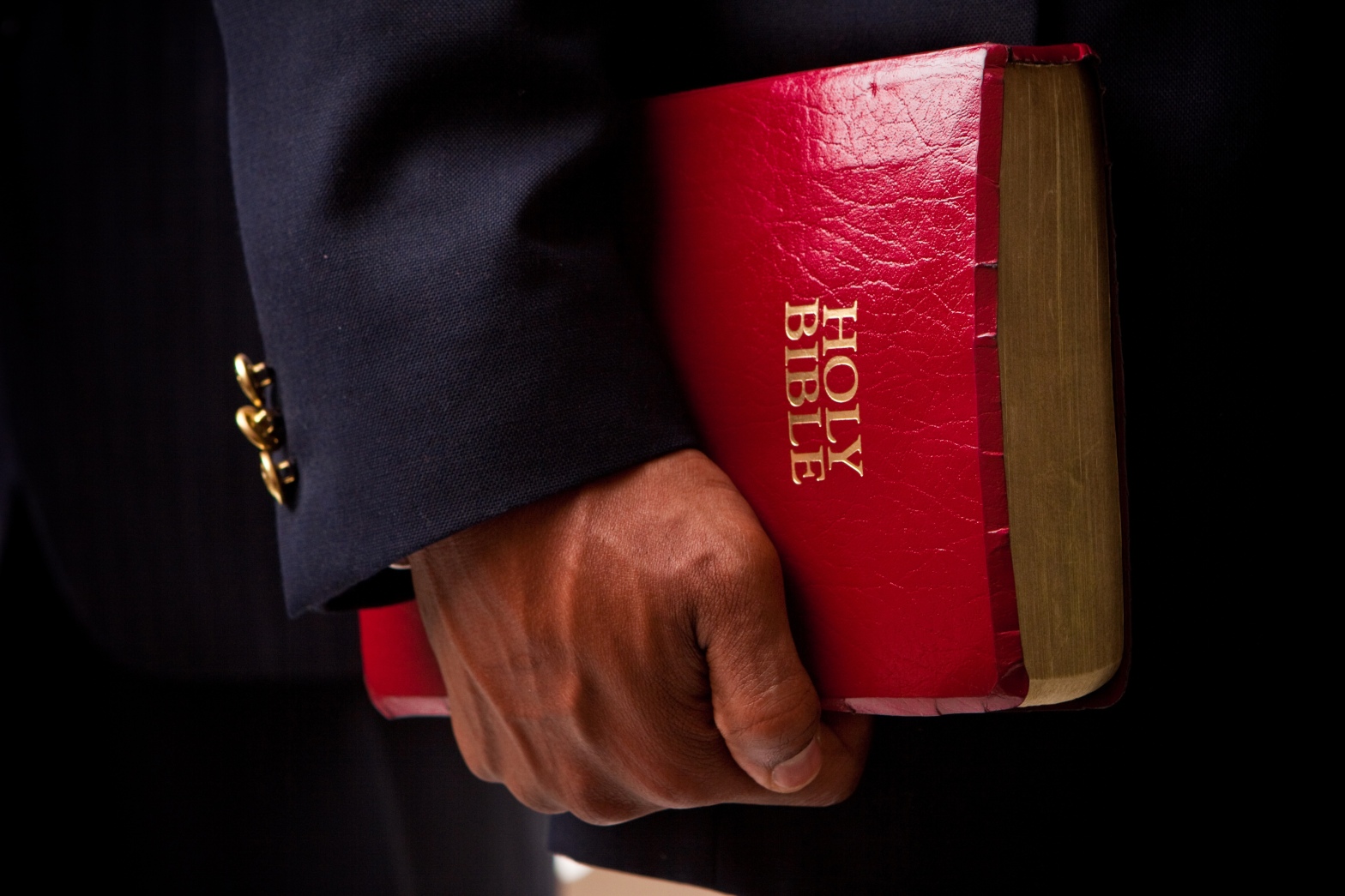

Video

It was at this point that the court was shown a short clip of KT preaching. After watching it, the judge addressed the family directly stating, “when I saw the video, it made me think that some people are born with charm… it’s perfectly obvious that [KT] was born with the gift of charm”.

Witness 5: KT’s Friend and fellow pastor

This was the first witness produced on behalf of the family. He explained that he has known KT for over 35 years, and when describing their relationship, he said KT “is like a brother to me”. His friend spoke of how they had met when he was going to school near to where KT’s family owned a restaurant. He said they became friends after KT joined the same school where they would both attend a faith group for students. From then, they would try to “preach the gospel” and “reach the people” in their neighbourhoods. When KT moved to the UK, he explained that they would still speak to each other “a few times a week”.

When describing KT, his friend stated that he was “the type who will put his faith over everything else, he will gladly let everything go and just follow God…that was his life”. He described how he knew KT and “his theological views and views on several subjects”. He talked about KT’s belief in the sanctity of life which meant that he was “against abortion and euthanasia”, and “anything that directly or indirectly takes away life or puts it at risk”.

After being given several scenarios by the judge as to what KT would do or believe would be the best thing to do in those situations, his friend clarified that “anything that has to do with exercising human power to end life will not have his support” as it is something “God should decide”.

It was mentioned earlier in the hearing that there was the belief that KT may not want to continue treatment if he knew that it would have a negative impact on his friends, family, and the clinical team. KT’s friend was asked by Francesca Gardner, counsel for the family, whether they had discussed a scenario like this.

“It’s been said KT might take into account the impact of his situation on his clinical team and the family. Did you discuss that with him?”

“Specifically in relation to this situation, no. But he cares about people, that care and compassion and sense of empathy and trying to make sure he’s a blessing rather than a burden – these are all inspired by his belief in God. Now, this same God, he believes, expects him to respect the sanctity of life, so he will not allow his love for people to triumph over his faith in God or his belief that God can bring about a miracle, or take that to mean that he can decide when his life ends. He will not care about people to the point of offending God. Because his care for people is inspired by his love for God. So, the decision to do something that he does not believe will be pleasing to God will decide the boundaries for him. There is a truth to saying that he would not want to be a burden. That is consistent with his personality and character. But it goes too far to assume that because of his love and consideration for people he would say ‘I don’t care what God thinks – doctors think it’s over – just pull the plug on me’. That is a stretch too far. I don’t see him doing that.”

Counsel for the Trust asked about the history of the relationship between this witness and KT, and the judge intervened to enquire what they liked to do together when they weren’t being pastors – to which he said that they would often debate on global issues and theological matters, go out to eat together, go shopping or do business research. The judge followed up by asking what was KT’s favourite food and how he adjusted his diet when he first became ill. KT’s friend explained that “he [KT] started eating more vegetables, he did a lot of research to identify what was okay or not to eat and so he adjusted his life to eat more natural food and drink more water”.

Mr Sachdeva picked up the cross-examination again, asking whether he had discussions with KT about what it would be like to be in a coma. He said that they hadn’t, “not in the context of him or me or anyone we know being in a coma,” but that they had discussions about other people. He explained that the subject of euthanasia was debated often in the area where they used to live. He and KT had conversations as there was “a situation where someone was in a coma and there were people of the view that their life should be terminated and [KT] did not share that view”.

“What do you mean by ‘euthanasia’”, asked Vikram Sachdeva.

Friend: I know that’s a technical term – but I can tell you what it meant to us at the time. Human beings were going to make decisions about whether to continue or to end another person’s lif, because of a desperate situation where a person is never going to recover. So, to make it more bearable, let it end now. We used the word not as experts but as, “hey, this person is alive thanks to the machines, which have been invented by people who received knowledge and wisdom from God. If God wants the person to die, the machine won’t keep the people alive, because some people go on the machines and die anyway. Let’s stay away from saying ‘we’re going to stop this now'”.

Sachdeva: So, your view is doctors can never stop providing life-sustaining treatments for someone who is still alive?

Friend: If there’s any technology keeping a person alive, that comes from God, and people capable of rendering that care should keep that care going.

Sachdeva: So what you mean is ‘yes’.

Friend: Yes. Doctors should prolong life when they have the ability to do so.

Sachdeva: Should doctors ever withdraw treatment from a patient who is alive.

Friend: Theologically, no.

Sachdeva: From KT’s point of view?

Friend: I would say KT would be saying ‘no’ to that too. Based on my knowledge of him.

The Official Solicitor then took a turn to cross-question the friend.

In terms of KT’s prognosis, his friend said, “we honour and respect the doctors and hear what they have to say but never take their words as absolutely final” because “there’s another layer of power who is God” who can intervene. He said that KT has already lived longer than he was expected to, therefore there is always a chance for a “miracle”.

His friend was made aware by Ms Paterson that the evidence provided to the court indicated that ,despite the efforts of the treating team, and the fact that KT has lived longer than expected, the medical evidence is that his death is inevitable in the next six to seven months. There was a risk that KT could die “rapidly and unexpectedly” and “alone”. His friend answered that he believes when people have chosen a path, they have made their own choices. He likened it to being a soldier.

“They join the military and put on a uniform, and travel to another nation to fight in defence of their countries, their fellow citizens. They kiss their wives goodbye on their way to strange countries, never sure they’ll come back. When a person makes a choice of a lifestyle, to believe in God and the principles of the Bible, that person is also making an indirect choice. …. If you can leave your wife and go abroad, there is no question that you have a higher vision. The day you decide to follow Jesus, you are saying your life is no longer your own.”

The judge intervened again.

“The picture that Ms Paterson was painting for you showed you that there are different scenarios for KT’s death”. He said that KT was susceptible to hospital infection and could, essentially, drown in his own bodily fluids. “My every instinct as a judge and as a man is to spare [KT] from that if I can”.

He engaged in some theological discussion: “I think Pentecostalism believes that man is made in the image of God and how we treat men is how we treat God” t- o which KT’s friend agreed. The judge went on to say:

“Now, I have said in many cases there is something intrinsic to the human condition that carries dignity with it, and we have an obligation to preserve human dignity. The scenario I’ve just outlined to you does not preserve KT’s dignity as a human being, and it causes him avoidable pain and effectively protracts his death, rather than keeps him alive. I don’t have KT here to be able to answer this question, but I am persuaded he was a committed Pentecostalist. Tell me what your position would be.”

His friend answered, “I’m not claiming to be a voice for Pentecostalism, but I can tell you my view – and this is a very important part of our theology. We will not promote poverty or anything that we believe will cause people pain, but we are familiar with the fact that we do not have an ideal world. And in this world, we try everything within our power and with the grace from God to create an ideal world, but we recognise the limits to where we can go. Let me give you an illustration”.

“No”, said the judge. “I want you to deal directly with my scenario. You think he would rather go through that dreadful death?”

“Yes”, he replied. “People who think otherwise will think so out of love too – but he would not choose to end his life. He would rather go through humiliation”.

Witness 6: KT’s wife (JO):

After a short break, KT’s wife was invited to speak to the court. She described KT as “a caring person. He’s a believer, a good friend, a confidente” and said that “he’s been through a lot but never allowed the situation to get the best of him”.

She said that she visits him “sometimes four times a week” due to work and said, “he is a good person, I would do anything for him”. She felt that KT knows she’s there when she visits. And when she plays recordings of sermons it’s her belief is that he hears them.

When asked about what she would say about whether or not treatment should stop, JO said, “it’s a life event. He didn’t allow his condition to bring him down. He did his research to see how he could improve. He tried his best to get better”. She told the court that they never had a discussion as to what KT would want to happen if he were to become as poorly as he is now.

Judge: Thinking about situations when you see him struggling to breathe, or someone suctioning his throat in situations that are very distressing to watch. We don’t have to have that.

(She shakes her head)

Judge: You could avoid it.

Wife: He’d want to leave it to God.

JO described to the judge how KT did not tell her for a while after he was diagnosed with kidney failure because “he didn’t want me to worry”. The judge told her “I think you had a very happy marriage” to which she said, “I tried to make him feel happy because I didn’t want him to feel bad about his situation”.

When the judge said that if it were left to the prospects of a miracle, which would be unlikely, the course of events “will be very sad for both of you”. JO responded, that while she would “definitely want to be there…as a Christian, we take each day as the last day you will live on earth”. She said that “even if we’re not there, we visit him, so he knows he is loved”.

Counsel for the Trust then proceeded with the cross-examination. Mr Sachdeva asked JO whether she believed that KT’s condition had deteriorated and whether she accepted the evidence from Dr W and Professor Wade. JO stated that she didn’t accept the evidence provided by Dr W and Professor Wade and disagreed with the belief that KT has deteriorated neurologically. She said that she “wouldn’t say he’s gotten worse” because “he was getting irritated with the pipes in his nose and would try to pull it out…he opens his eyes, he moves his legs and left palm”.

JO was concerned that, if treatment were to continue, the plan would be to move KT into a nursing home. She asked, “wouldn’t it be best for him to stay in the hospital?” as he is currently receiving his treatment there and “they know what to do”. However, this was not an option proposed by the Trust. Mr Sachdeva told her that “if the application is refused, then the Trust will seek to discharge your husband to a nursing home, as he does not need hospital care” but assured her that “he will go to a suitable nursing home” where they are trained to provide the treatment KT needs.

KT’s sister (GT):

Although there was no further formal evidence, the judge asked KT’s sister if she could tell him about KT. GT, who joined virtually, described her brother as “a lively person and very active, very caring” – someone who “doesn’t take no for an answer…he is a fighter and doesn’t give up”.

When talking about the prospect of treatment continuing for KT, the judge said that he “may pay a very high price” and experience a “painful death”. Similar to JO, GT responded saying that KT knows who is around him and knows that they care for him.

The judge said that if he followed the family’s wishes “it would lead to a very painful death for [KT], do you think that’s what he would want?” JO said yes, she believed that is what he would want. When the judge raised the concern that KT would be “effectively choking on his own secretions”, JO responded saying “death is death, it is God’s will”.

Closing discussions

The judge spoke to her and the rest of the family who had joined virtually and said, “I appreciate how extremely difficult this must be for you”.

The evidence seemed to indicate that KT would have wanted treatment to continue. The judge stated that he found “the evidence compelling as to what [KT] would want”, but now had to confront that if it were the case that KT would want treatment continued (which could still be disputed), what weight would be given to KT’s wishes, values, beliefs, and feelings in determining best interests. Especially as the evidence indicated that continuing treatment could lead to an uncontrolled and painful or distressing death for KT. He asked counsel to address this question:

“If I come to the conclusion that this is what he would have wanted for himself, however painful, and however contrary to most people’s instincts, as a man rooted in Pentecostal faith, how determinative is that of the Court’s decision?” He pointed out that KT’s human rights were engaged – including his right to exercise autonomy in the later stages of his life. “Would it be wrong to impel people to treat him in this way? I don’t know. Would it be contrary to their ethics? I don’t know. Is it workable and capable of preserving his dignity… I think we really are in the territory of what if those are his wishes and feelings, and what that means for best interests”. This was the issue he asked counsel to address in written submissions the following day when the court reconvened at 10.30am.

DAY TWO

Closing statements

The judge had been sent written closing statements by 10.30am. I requested the closing statements from the Trust and counsel for the family, but only received the Trust’s closing statement. (Celia received all three and used them to help me with this section.)

The closing position of the Trust was that it was not possible to infer from the fact that KT was a Pentecostalist that he would have wished to continue to live in a coma, with the very significant burdens that life holds. There was no direct evidence (said the Trust) about his past wishes and feelings relating to this situation – no witness even claims to have had a conversation with him about this. He has no ascertainable current wishes or feelings. In any case, a person’s values, wishes, feelings and beliefs are not determinative of a best interests decision. The Trust cited extensive case law to that effect.

The closing position of the Official Solicitor was also that it was not possible to be sure what KT’s wishes would be in this situation, because he “never contemplated the terrible reality of his present circumstances, which were outside his experience and probable knowledge”. The OS argued that “The court cannot know how, had he known thi,s KT’s views may have been refined… It must be live to Lady Hale’s observation in Aintree at [45] that ‘[even] if it is possible to determine what his views were in the past, they might well have changed in the light of the stresses and strains of his current predicament’. This is not in any way to undermine or belittle the strength of KT’s beliefs, but is to recognise the reality of human experience, i.e., we adapt and reflect upon our beliefs, in the face of circumstances”. The OS submitted that the Trust’s application should be granted so that KT’s death would be peaceful, with full symptomatic relief and his family present. To continue treating him, they said, would be to deprive him of “the last vestiges of his dignity and comfort”.

The closing submission from the family was that all the evidence showed that if KT were able to decide he would elect for treatment to continue. He had dedicated his life to God, and for him there are no limits or exceptions to sanctity of human life. He would not support a decision to bring about the end of his life in any circumstances. This is not a case where the court has only one option. There is a formulated option for KT to continue his treatment until such time as he dies naturally or, as the family hopes, there is a miracle. It has not been suggested at any point that the treatment plan is not an available option for the court to consider, or that any aspect of the plan goes beyond that which the clinicians would be willing to provide. It is the family’s unwavering position that treatment should continue because this is what KT would want for himself.

Delay with a ‘sensitive matter’

I used the link I had received the previous day to access the hearing, making sure I was ready at least 15 minutes before the scheduled start time. However, the hearing did not begin until a little past 11 o’clock. The judge was told by Ms Paterson that a sensitive issue had arisen. She made an application to the judge that this matter should not be made public. The judge was required to decide whether it would be appropriate for members of the public, the family, or the media to be present for this part of the hearing and he decided to ask everyone except the lawyers to leave the platform while he heard what it was that had arisen. Members of the public and the family were asked to leave, and the hearing was converted to a private hearing to deal with the sensitive matter. It was made clear to us prior to leaving that if it was determined that we could rejoin, we would be made aware.

It was just under two hours later that Celia Kitzinger contacted me to say that we were able to rejoin the call. However, when we tried to rejoin we were denied access. There was some confusion over the coming hours as to what was going on and when we were to be readmitted with the answer being ‘soon’ but with no definitive time set.

We were eventually readmitted at around 2.40pm at which time the judge informed us “I have to be limited in what I can say. I apologise if it sounds rather delphic. This morning an issue arose that may have had some bearing on the issues in the case. In the event, and having heard from the counsel, I have concluded that the material is not relevant to the decision I have to make. It’s deeply sensitive, and because it is not relevant it does not need to be in the public domain. I will set out my decision on that in a separate judgment, which will not be placed in the public domain.”

The closing statements from the Trust, the family and the Official Solicitor were then discussed. It was agreed that all parties were happy not to provide an oral submission, but to leave it with the written submission. However, Ms Gardner told the judge that “in the event that it’s in [KT’s] best interests to stop treatment, the family would ask for a period of time to visit [KT]”.

The Official Solicitor applied to withhold the name of the Trust from the public domain. The Judge said that there would have to be “powerful reasons” as to why the Trust should not be named. Ms Paterson acknowledged that the “practice of the court is to name the Trust” but argued that the judgment would have to deal with KT’s age and religious background which may allow the public to determine his ethnicity, amongst other things, and combined with his brain injury it may make KT identifiable to the public if the name of the Trust is known. As a result, it was requested that the “Trust not be named between now and three months after [KT’s] death whenever that may be”.

The judge stated, “excluding the names of Trusts bringing applications to withdraw treatment…greatly unsettles the public”. He explained that it can “have a corrosive impact not only on public trust in the healthcare system but also on the confidence in the court”. The judge refused the application stating that he did not believe “the relatively short-term advantages of not naming the Trust outweigh the very strong disadvantages of undermining the public trust in the process of this court and the healthcare system”.

The judgment was then scheduled to be handed down at 4.15pm.

The judgment

I rejoined the link and the oral judgment commenced at roughly 4.40pm. The judge found that KT was in a prolonged disorder of consciousness, stating that a “compelling medical consensus established that he [KT] has no awareness or scope of rehabilitation”.

He summarised that KT “is dependent on dialysis three times a week to keep him alive, but it has become increasingly difficult as his blood pressure drops which carries risk of further brain injury, cardiac arrest or heart attack”.

The judge acknowledged that the family holds a “strong Pentecostal Christian faith” that means they have “belief in the power of prayer and miracles” and “confidence in the power of God to cure the sick, however parlous”. He also acknowledgesdKT’s faith, his role as a pastor and as an active member of the church. “He [KT] was a very highly regarded and popular preacher”.

Speaking of the family, the judge said, “[KT’s] family feel that his faith was such that he would want his life sustained for as long as possible. They do not proactively dispute his prognosis but feel he has a greater level of awareness than the Trust proposes”. They believe that KT is “aware of their presence and they have, on occasion, observed meaningful responses”.

If treatment were to continue, the judge acknowledged that KT “cannot remain indefinitely” in hospital and “would need to be put in a nursing home” that would be able to appropriately care for him. He stated that the Trust’s “multidisciplinary team agree that treatment should be removed and he [KT] should receive palliative care only”. The process leading to KT’s death would be managed by the Trust, and it would enable KT to have his family around him. In the hypothetical end of life plan proposed by the Trust, the likely cause of death would be due to the withdrawal of dialysis after which it is estimated that KT would “likely die within two weeks”.

The judge stated that “whilst there is disagreement…it is also important to emphasise there are high levels of respect and mutual understanding”.

The judge spoke of the pastor in KT’s church who had described KT as “a man of stubborn faith” who believed in the supernatural power of God and would be strongly against withdrawing any form of treatment from anyone. “Even when confronted with pain and his own death he [KT] would still respect sanctity of life”.

Speaking of KT, the judge said, “[KT’s] popularity as a pastor is, in my view, not only because he was manifesting a charming and engaging personality but also because his faith was so evidently genuine and sincere”. He said: “the code by which he lives his life is clear…I find that [KT] would have chosen to continue with life sustaining treatment even in the face of a coma and with a terminal diagnosis”.

The judge found that – contrary to the closing arguments presented by the Trust and by the Official Solicitor – there was compelling evidence that KT “would not have wanted treatment withdrawn” – and that he would “rather suffer and hold out for a miracle”.

However, the judge said that “dialysis for [KT] can achieve nothing, it is both burdensome and futile”. The plan to sustain treatment would “cause harm without delivering benefit and it would cause great distress for the treating team to act in a way that would become contrary to their own professional principles”. He stated that he believed KT would be “the last person to want to impose such a burden on anyone else” and said that “it is plain from all I have read that he was both a kind and gentle man”.

The judge said, “I have ultimately concluded that the application by the Trust is well founded… I can tell KT that which he would want to know, namely that everything possible had been done. I do however think that the family would want to say their goodbyes directly to KT and that he too would very much have wanted that. Family, plainly, was important to him”. The judge stated that the declaration is not to be put into effect until “twenty-one days from today’s date so they [the family] can arrange flights from diverse parts of the world, but it would be inappropriate to go beyond that period”.

The judge expressed his gratitude to counsel for their assistance, acknowledging that challenging and difficult cases like these can “take its toll on everyone concerned”.

REFLECTIONS

This case, like many others I have attended, greatly emphasised the importance of advance care planning (ACP). ACP is a process through which you can document your personal values, goals, and preferences regarding future medical care, appoint someone to make decisions for you if you can’t, and – if you want to – you can make legally binding treatment refusals. It was frequently mentioned in this case that there was not sufficient evidence to support the claims that KT would want treatment to continue. However, we were not made aware as to why, despite being ill with end stage kidney failure, KT had not (apparently) been supported by his health care team to explicitly discuss his wishes with them and with his family members, and why no advance care plan had been drawn up.

Undeniably, conversations about death and dying can be incredibly difficult and daunting, and there are a number of reasons as to why people – including doctors – avoid having these discussions and making an advance care plans. These reasons could include a lack of awareness, cultural or religious beliefs that conflict with planning, or general discomfort with the topic. However, it’s cases such as this one that highlight the importance of having a plan in place because even though KT’s family and friend were all unanimous in the belief that KT would want treatment to continue, and the judge accepted that this was KT’s position, it was ultimately decided that it was not in KT’s best interests.

This case highlighted the intricate and complex nature of best interests decision making. The judge in this case acknowledged the compelling evidence that KT would have wanted treatment to continue, which the doctors were willing to continue to offer, yet decided that continuing treatment would not be in KT’s best interests. His decision not only draws attention to the diverse considerations that encompass best interests decision-making, but also suggests that ‘best interests’ extends beyond adherence to the past preferences and beliefs of P. It seemed in this case that the decision was made by considering not just KT’s beliefs and values but the medical evidence and expertise, potential outcomes, and the possible impact on the well-being of KT as he is now. Furthermore, and as expressed in the closing statement of the Official Solicitor, it cannot be truly known whether, in light of his current situation, KT would hold the same views. As a result, it’s clear that while KT’s religious beliefs and values are important to consider, they are not the sole determinant. Rather, the decision is made through the consideration of a range of factors.

As a PhD student who is currently researching media representations of end-of-life decisions, the mention of a ‘good’ death and its opposite – a ‘bad’ death – was something I noticed in this case. with comments like “a good death is possible… only through careful planning and avoidance of distress”. When discussing a potential risk for KT in developing an infection that could essentially drown him in his own bodily fluids, the judge expressed his wish to “spare” him from that death, implying, to me, that it was undesirable. The concept of a ‘good’ death is often present in research pertaining to end-of-life and palliative care, although what constitutes a ‘good’ death is difficult to establish. There are also several studies that refer to the impact media coverage can have on public understanding of a ‘good’ death including the identification of certain circumstances that are deemed ideal – such as being surrounded by loved ones. Meanwhile other studies have considered the media’s ability to influence and shape cultural understandings of what constitutes a ‘good’ death. It made me keenly aware of the impact and influence cases such as this can have in shaping public understanding of a ‘good’ or a ‘bad’ death. However, it can be argued that the definition of a ‘good’ or ‘bad’ death is subjective – as personal or cultural beliefs can impact an individual. in this case I couldn’t help but question whether for KT, a ‘good’ death would be one that was, in his eyes, decided by God, or whether a ‘good’ death would be one that was as painless as possible and one where he was surrounded by his loved ones?

Brain Farmer, PA journalist, also observed much of the hearing and wrote about it in The Independent: Wife of brain-damaged pastor loses life-support treatment fight. It was interesting to read what he had written, especially in comparison to how I approached writing this blog. There’s no question that writing a news report, and writing a blog requires different approaches even when they both include information that stem from the same source. As suggested by the title, the news report has a significant focus on KT’s wife. This can make the case more relatable and emotionally engaging for the reader whilst also highlighting the contrast between the views of KT’s wife (and loved ones), and the views of the medical experts. While this focus emphasises the newsworthiness of the case, the report also delves into the key points of the hearing. Brian Farmer explores KT’s medical condition and treatment, the family’s beliefs and religious considerations, key points of the legal proceedings and the judge’s ruling. The article also highlights the ethical and moral dilemma and challenge of balancing deeply held religious beliefs with medical realities. It’s interesting to see the details that journalists like Brain Farmer pick out and to think about how news reporting of cases such as these could help develop public understanding of the Court of Protection and of end-of-life decision making. News reports such as this make information accessible, and easily digestible in terms of its succinctness. However, blogs can offer more context by providing an extensive account of what unfolded during the hearing moment-by-moment. Together, they can cater to a wide audience, potentially increasing engagement and providing balanced coverage of the case that caters to the various levels of interest and, hopefully, developing a more informed public audience.

Finally, discussions relating to the transparency order also piqued my interest. The Court of Protection has, in the past, been referred to as a ‘secret’ court in which judgments were difficult to access and hearings were often held in private. It was encouraging to see the judge in this case consider the detrimental impact withholding information (the Trust’s name) could have on the public. It is not contested that the privacy of those involved in these cases should be respected, but it is also important to ensure that the public are able to access information that could develop their understanding of the court’s processes and how end-of-life decisions are made.

As we have also seen in the dispute present in Independent News and Media Ltd & Ors v A [2009] EWHC 2858 where it was determined that there was “‘good reason’” for the media to be present at the hearing “with the potential for reporting its outcome”. In that case, the judge, Mr Justice Hedley, highlighted three reasons as to why he concluded that there was ‘good reason’ in this case. They are as follows:

First, all these issues in principle are already within the public domain and the questions which they raise are readily apparent. Secondly, the court is equipped with powers to preserve privacy whilst addressing the issues in the case. Thirdly, the decision of the court will have major implications for the future welfare of ‘A’ and it is in the public interest that there should be understanding of the jurisdiction and powers of the court and how they are exercised. It can be objected that the second and third reasons above could apply to almost any case, and it is important to stress that it is the combination of those three reasons that impels my decision; by the same token it should not be assumed that the first standing alone would necessarily be sufficient. (my emphasis)

The ability to observe and read about cases can greatly aid the public in our understanding of the court process and end-of-life decision-making. Statements such as these point to a shift in attitude of those involved in the court in acknowledging the benefits and importance of transparency and openness.

Rhiannon Snaith is an ESRC funded PhD student at the School of Journalism, Media and Culture at Cardiff University. Her research focuses on media representations of decisions about life-sustaining treatment, specifically for those without the capacity to make such decisions for themselves. She has previously blogged for the Project here and here. You can learn more about her work by checking out her academic profile and her Twitter profile.

[1] This quotation was supplied by Celia Kitzinger. All extracts purporting to be direct reported speech from the hearing are drawn from contemporaneous notes made by Celia Kitzinger and (with this sole exception) Rhiannon Snaith, and cross-checked for accuracy. However, we are not allowed to audio-record hearings and they are unlikely to be 100% verbatim.

2 thoughts on “Withdrawing treatment from a pastor in a coma: Balancing religious beliefs and medical realities”