By Amanda Hill (Anna), Pippa Arnold, John Harper, Gail Heslop, Ellen Lefley, Celia Kitzinger, Claire Martin, Tess Saunders and Ann Wilson (co-ordinated and curated with an introduction by Celia Kitzinger), 25 October 2023

Introductory Editorial Note

This is the second collective blog post about a fact-finding hearing before Mr Justice Hayden, observed (in part) by more than 30 members of the public. The first collective blog post is here: “Tampering with equipment or failings in care? Part 1”. The case has been the subject of two previous judgments by Mr Justice Hayden: Re G [2021] EWCOP 69 and Re G[2022] EWCOP 25. They provide essential background.

Fact-finding hearings arise when one party makes allegations against another that are of significance and will impact upon decisions that need to be made – in this case, where the vulnerable person at the centre of the case (G) will live, and the contact she’ll have with family members. The ICB (Integrated Care Board) is making serious accusations against the family, including that they’ve tampered with G’s medical equipment, putting her at risk of harm. The family have made counter-accusations saying that staff at the care home don’t provide safe or adequate care. For more information about the background to this case, and for some responses to the first part of the hearing, do read the earlier blog post. We’ve also documented aspects of this case in two previous blogs: see A judicial embargo and our decision to postpone and Fact-finding hearing: “Little short of outright war”

This collective blog post is composed of a kaleidoscope of 9 different pieces from people who observed the second part of the hearing (in late July or, after the adjournment, in October 2023). Each presents a different ‘snapshot’ of what they experienced of the hearing from a range of perspectives, including that of carer, family member of a vulnerable person, social worker, justice policy expert, former litigant-in-person in the Court of Protection, psychologist, and paralegal. The case is still ongoing at the time this blog is published and it’s likely we’ll be publishing further reflections on the closing statements and eventual judgment.

Where we’ve quoted from the hearings, we’ve relied on contemporaneous notes and they’ve usually been cross-checked with at least one other observer. They are as accurate as we could get them but as we’re not allowed to audio-record hearings, it’s unlikely that they are entirely verbatim – especially as (as various bloggers note) the audio was of poor quality for parts of this hearing for people watching remotely.

1. Representation and dignity for disabled people

By Ann Wilson

Thank you for providing me with the opportunity to observe yesterday’s court proceedings.

I was heartened to see the judiciary expertly at work and doing justice in open court.

The family have tragically overcome many difficulties and travelled a long way on their sad and fraught journey with their daughter in care. l hope they will find comfort and continued strength to achieve the best outcome for their precious daughter and can hereafter tenderly care for her safely at home. I trust the court will help this young woman, and her family, following what must have been a very harmful and distressing time for them.

Like so many families, I know the pain of seeing your relative neglected in care and unable to move without the assistance of others. Care homes, in our family’s experience, are profit-making businesses mostly staffed by poorly-paid untrained staff struggling to make ends meet. I have seen totally false allegations made by care home staff/ manager to protect themselves against families and to justify neglect when funding has been reduced and one-to-one care removed by the Integrated Care Board. Court protection is vital.

.Thank you for all the Open Justice Court of Protection Project has done to help us show the world of care for the disabled. They need representation and dignity.

2. A total breakdown of the relationship between those caring for G and her family

By Pippa Arnold

I observed the sixth day of this hearing via MS Teams (25th July 2023 – all day). The Open Justice COP Project provided a summary of the case so far, and I was keen to observe given that it centred medical treatment (which is my primary interest in COP proceedings) and the serious nature of the allegations being made by the care home. Moreover, Mr Justice Hayden had been quoted in a newspaper article (here) as having said “in 10 years, I have never had to try a case like this in the Court of Protection” which intrigued me.

Ms Khalique KC (Counsel for the Applicant – the ICB and care home company) informed the court that there were 3 witnesses to give evidence that day.

The first was a senior healthcare assistant at the care home. When giving her oath, I noticed how nervous she was, as she was shaking and taking deep breaths. I had presumed that this was because giving evidence can be a daunting task, but I later realised that G’s father (who she had alleged purposely intimidated her, shouted at her, and singled her out whilst she was caring for G) was also in court. We later found out that the witness now only cares for G at night times as she was suffering from panic attacks when G’s family attended during the day. Furthermore, the witness clearly cared for G stating that she “loves caring for [G], she’s an amazing young woman”, and so, it was difficult for her to talk about these times when she was very unwell.

This witness’ evidence took approximately 3 hours and so, the court did not break for lunch until nearly 2.00pm. When she was being cross-examined by Mr Patel KC (Counsel for G’s father), I thought that Mr Justice Hayden was very supportive of the witness. For instance, one of the main issues related to an allegation that G’s father had tampered with her medical equipment. Mr Patel KC had established that G was taken to hospital around 9am that morning and visitors were not allowed into the care home until 10am. Consequently, he stated that G’s father never went to the care home on the day in question and instead, went straight to the hospital. The witness responded timidly with “ok”. Mr Justice Hayden then told the witness not to give into Mr Patel KC and if she thought what he was saying was wrong, she should say so. The witness took this onboard and subsequently told Mr Patel KC that she was “100% certain” that she had seen G’s father at the care home that day.

When the witness finished her evidence, Mr Justice Hayden said that he hoped she did not have to go through a hearing like this one again, which acknowledged the distress it had caused her and demonstrated how unusual fact-finding hearings are in the COP.

This was my first experience of observing a COP hearing where witnesses were cross-examined. I found it interesting as the nature of cross-examination differs from the COP’s usual collaborative approach. Despite Counsel and G’s grandmother (as she acted as a litigant-in-person) having to ask difficult questions and challenge the witness’ credibility, they were not unduly harsh and were conscious of her emotions. For instance, Mr Patel KC acknowledged that the witness was getting upset and so he stated that he did not want to sound as though he was criticising her, before asking if she would like to take a break. G’s grandmother also told the witness that she knew that she cares for G very much.

The facts of this case were upsetting, as it demonstrated a total breakdown of the relationship between those caring for G and her family. I will be interested to see how this matter progresses and what Mr Justice Hayden concludes as, in my opinion, Counsel did cast doubt on the accuracy and credibility of the Applicant’s witnesses’ accounts on the day I observed.

3. The importance of accurate record-keeping

By Gail Heslop

As a social worker, I often read court judgments to inform my practice. Many of these key judgments are made by Mr Justice Hayden, so after reading an overview of this case before Mr Justice Hayden (Fact-finding hearing: “Little short of outright war”), I was intrigued – and keen to experience for myself the court process on the basis of which he arrives at his judgments.

I emailed the Open Justice Court of Protection Project and received the video-link promptly, along with some information about joining with my camera and mike turned off, and the fact that there was a Reporting Restrictions Order which would be sent to me by the court staff (and I received it the next day).

It was a multi-day hearing and I watched just the morning of Tuesday 25th July 2023 (the sixth day of the hearing). The main event that morning was that a Senior Health Care Assistant from G’s care home was in the witness box, giving evidence relating to the family’s alleged tampering with equipment. Her written evidence had been submitted to court and now she was being sworn in (or affirmed) and cross-examined about it by each of the parties in turn – mainly by counsel for G’s father, Mr Parishil Patel (PP). Some of her written records were put up on the court screen for everyone to see while she was being asked details about what happened.

As I start writing about the experience, I am reflecting on all the different perspectives I am writing it from.

- As a social worker, Deprivation of Liberty Safeguards Assessor (and former carer). I am currently a social worker who has been in practice for 13 years. Before this, like the witness, I was a carer for 7 years. In this time, and in both roles, I have written lots of records myself and also overseen other workers’ written records. In fact, I now train people on the importance of keeping accurate written records and being clear about the difference between fact and opinion. As a social worker, I often come across complex safeguarding concerns involving paid carers and family members being accused of wrongdoing which has put the person at risk.

- As an expert witness in the Crown Court (and I’ve also prepared evidence for the Court of Protection). I recall that, even as a professional, I was ill-prepared for my first time presenting evidence in a Crown Court as an expert witness. Unlike this witness, I was merely being asked for my professional opinion – my own practice and the accuracy of my written records was not in question. It was really only on arriving at the court that I realised the gravity of what I was actually being asked to do. Counsel for the prosecution advised me what to expect and that was the first time it dawned on me who would be in the court room; the defendant and their family, the victim’s family, the judges, court staff and all the various counsel. I was told I would be at the centre of the court on an elevated stand before the judges (plural in the case I attended) and any others in attendance and that I would be cross examined by the defence, who quite frankly would be trying to discredit any evidence that I gave which went against their client. I had some really good advice from colleagues beforehand which was if you don’t know, say you don’t know. This might seem obvious but when you are under pressure there can be a temptation to try to guess, but you’re in a court room which is relying on you to be as accurate as possible.

On the morning I observed, the witness was extremely nervous. She was visibly shaking, hyperventilating, and at times crying, making her hard to understand or even inaudible. As a social worker, I’m trained to empathise and build up a rapport with the people I support, so I was interested to see if the judge and counsel would pick up on this and how they would respond. I was pleased to see that Mr Justice Hayden stopped the witness on several occasions – at one point stressing that her role in the care home was ‘much more demanding than what’s going on in this court room’. He gave practical advice to support her to reduce her anxiety, and patiently gave repeated prompts for her to speak up. I also noted the counsel acting for G’s father was patient and showed no outward signs of frustration, despite a very long examination where the witness needed support to find documents (one of the junior barristers came to the witness stand to help her): and she also needed to have a 15-minute break due to her distress.

I found myself wondering what preparation and support this witness had had. Had her manager come to court with her today? Was she given (paid) time to prepare for giving evidence? Did she have the opportunity to come and look around the court before the hearing? (Many courts offer this in recognition of how stressful being a witness is.) In my experience, many people who are anxious will begin to relax as they focus on the questions, but I observed that this witness did not – despite everyone’s support. I felt that everyone in the court was very mindful of this and when it became too much for her, they took appropriate steps to support her as much as possible.

At the start of the cross-examination, the witness was asked about her written record of an incident whereby she recorded that the wet circuit for G’s ventilator (the ventilator plugged into the wall in her room in the care home) “appeared to have been tampered with” and pieces “seem to have been swapped over”. It was on a day when G was taken into hospital. The family had been in G’s room at the care home to pick up some of her things, and the witness had concluded that the parents must have tampered with it.

Counsel for G’s father (Mr Parishil Patel [PP]) pointed to evidence (from other care home records) that the parents could not have tampered with the equipment because they were not in the care home that morning: “Let me put to you that they were not there that morning. That they went directly to the hospital having been telephoned and told that G was being transferred”. The witness reacted by saying “okay”. The judge intervened to say: “Don’t say ‘okay’ and give in to him. Did you see them?” “I’m 100% sure” she said, and the judge replied: “Stand up to him. Don’t just cower. I know you’re nervous, but stand up to him”.

Witness: From what I recall, on that day they came to collect her belongings when G wasn’t there.

PP: They did, but that wasn’t until 8.30 in the evening. Could it be that you’ve misremembered this incident completely

Witness: Not completely, no.

PP: Maybe you’ve misremembered the date. What stuck out in your memory that day was the circuit in G’s room was wrongly set up and you have gone from the fact it’s wrongly set up to “[the parents] must have tampered with it”. And there are other explanations aren’t there, other than [the parents] tampered with the equipment?

Later (after the witness had taken a break to deal with her extreme anxiety), Counsel for the father returned to the question of “other explanations” that might account for the equipment being wrongly set up.

There were questions about the checklist that the care home use to do checks on equipment and to ensure appropriate infection control. At one point Counsel suggested if something was not on the checklist it is unlikely to have been done. However, from my own experiences of working in care, I know some things are done automatically without the need for a checklist, due to experience. So, it does not seem unlikely to me that something not on the checklist might have been looked at and checked, especially if it involved something as serious as oxygen delivery.

As questioning continued, more written records completed by the witness were viewed, including an occasion when G’s sats (oxygen saturation levels) had dropped below safe levels while she was being hoisted in her room and G’s father intervened to help his daughter. The father is someone – everyone accepts – who has developed expert knowledge about his daughter’s medical care over the last 28 years, and he’s her primary family carer, and has developed a great deal of skill in dealing with her needs. The witness said he was ‘man-handling’ G:

PP: You say dad was “manhandling” – six lines up from the bottom – is that what you really mean? I put to you that suggests he was rough with her.

Witness: Not rough – but it would have been safer to do it with the hoist, the equipment that was right in front of him

PP: You’re not allowed to manually move her, are you?

Witness: No

PP: That doesn’t mean that [Father] hasn’t worked out over the years that’s a safe way of moving her.

Witness: The sling and hoist equipment were there ready to use. We could have handled that situation

PP: What was necessary was for her position to be corrected as quickly as possible?

Witness: Yes, but there was equipment there. It could have been done more safely. It’s not a criticism of [Father] but it’s how we’ve been trained – to use the equipment that’s there.

I was struck by the witness’ lack of empathy for G’s father at the time of the incident, when he was observing his daughter clearly in distress and acting to relieve it. The witness did not seem to recognise the impression using the term “man-handling” would give to others. For me, I view man-handling as inappropriate contact with another person, perhaps roughly without good reason or consent.

Counsel moved on to ask about written records relating to an ambulance journey to hospital. This was a confusing interaction and I am not entirely sure what was being claimed or counter claimed. According to G’s father, the oxygen had not been properly delivered to his daughter during this ambulance journey. In her written report, the witness had stated (three times) that the oxygen used was care home oxygen and that it had been properly checked – but she now said that it was the paramedics’ oxygen

Witness: She went on paramedic oxygen. I’m 100% sure. We don’t do that.

PP: You saw that with your own eyes, did you?

Witness: I did yes.

PP: So why did you put three times in your records that it was [Care Home] oxygen that was used

Witness: That was clearly an error on my part – at the end of a 13-hour shift when I was feeling upset.

//

PP: Being on oxygen means being connected to it, the valve being turned on, and the dial, the flow meter, being turned from 0 to something. And you can’t say, can you, that before she left [the Care Home] that all of those three things were done.

Witness: All I can say, is the paramedics were doing it.

PP: So, is your evidence, NOW – because the paramedics weren’t part of the original note – that you didn’tcheck the connection?

Witness: It’s their equipment. I’m not going to check someone else’s equipment.

When the judge intervened to say “I think it’s being suggested to you that G’s oxygen would have been off all the time from the Care Home to the Hospital”, the witness said she thought that can’t have been the case because if so, “I don’t think she’d be here today”.

I was only able to observe for the morning, but I feel this gave me a really good insight into the evidence as presented by one witness.

On the basis of what I saw, I was left with the sense of either one of two possible scenarios. This could be a case where G’s family had tampered with equipment in ways that might have harmed her, but poor record-keeping was likely to make this difficult to prove. Or it could be a case where inaccurate and unfair record-keeping had resulted in G’s family being unfairly accused and deprived of contact with their daughter. Either way, the person at the centre of this, G, was likely to be suffering.

Observing this case has really reinforced my recognition of the importance of accurate record-keeping. I will definitely be using examples from this case in my training sessions to support workers to recognise what can happen when we don’t record factual, accurate information and consider the language we are using in doing so.

It has also made me reflect on how much we expect from care staff. The witness may well have had some basic recording training, but I doubt very much there was training around recognising her own biases.

This Senior Health Care Worker does not work in isolation. She is part of a team. Where was her supervision, her debriefs and where was the support she needed to recognise the importance of accurate record keeping and how to do it properly? Even if these structures were in place, it is clear from the situation in court that these were not enough. I have no doubt the witness will take away learning from this experience – but at what cost to her own wellbeing and to that of G and her family?

4. Perspective from a justice policy expert

By Ellen Lefley (@JUSTICEhq LinkedIn)

I used to practice as a barrister in the North East of England, where I had a mixed common law practice working in family, civil, and criminal courts, but not in the Court of Protection. I now work for JUSTICE, a law reform and human rights organisation which aims to improve the justice system to make it fairer, more accessible and more equal.

I watched the hearing for the whole day on 27 July 2023. I decided to do so because at the time JUSTICE was responding to the Ministry of Justice’s consultation on Open Justice, which closed in September 2023. (We highlighted the work of the Court of Protection Open Justice Project in our response.)

The hearing started in the middle of the care manager’s evidence, which had clearly begun the day before. I was able to pick it up and follow, and I’m not of the opinion that time should be used to explain everything from scratch each day, just in case someone new is listening. There has to be some responsibility on the observers to either attend the whole case, or to expect to have to pick things up as they go. There are limits to this of course – e.g., very specialist jargon or abbreviations may be worth re-explaining a few times during a case, if it is important to understand what is going on and it’s not inferable what it means. In this case there were already two previously published judgments and a summary of the issues before the court (and details about the parties involved and their representatives) available from the Open Justice Court of Protection Project website.

I’m going to make comments about 3 areas: (1) remote justice (2) cross examination (3) the judge.

1. Remote justice

Getting the link from the Open Justice Court of Protection Project was straightforward, more so than when I have had to, in the past, get a link with only a generic court email address.

In comparison to previous remote hearings I have attended, the main setback seemed to be the audio. The audio was unclear in parts, and at times there was a slight lag. Sometimes it cut out completely, namely when people spoke over each other. I winced a few times when the witness was cut off mid-sentence, and the audio for both witness and advocate suffered. The fact that the judge was quite interventionist also made it more difficult, with advocate, judge and witness talking over one another. However, the judge is a little different – when he cuts off the witness to tell him that he wasn’t answering the question, you can understand it more. When the barristers did it, it was a little more frustrating – they had asked the question and I wanted to hear the answer!

Viewing the documents in the case on the screen, as they were referred to in cross-examination, was excellent. I understand this was done to ensure remote witnesses could participate, but as an observer I was very grateful to benefit, even if unintentionally. The number of times as a law student – and sometimes as a pupil – I sat in hearings in which paperwork was referred to which I didn’t have, and I disengaged as a result! So much in cases these days is written and never read aloud in court, particularly in civil proceedings. There is also something more engaging about seeing the handwritten notes on screen.

During the period I was watching, there was a disruptive episode of note: someone had accidentally unmuted themselves and was loudly talking. The judge, witnesses and advocates paused, and it became clear that the remote observer was discussing someone’s care. The microphones were then disabled by the court – it said on my screen “you can no longer unmute” – suggesting that all observers had originally had the opportunity to unmute themselves and disturb proceedings in the first place. Perhaps to disable microphones for observers from the start in future would make a lot of sense? But I suppose the court hoped it wouldn’t be necessary. Also, I don’t think the learning point is that someone accidentally unmuted, but rather that remotely observing a hearing will be treated, by some, less seriously than attending in person. Someone clearly just had the hearing on in the background and wasn’t listening, and was in fact talking about other things – very private things – presumably in their line of work. This is not to be unrealistic about how busy people working in social care are: however, there is clearly a potential for remote attendance and observation to be treated casually, and this can impact the proceedings negatively.

2. Cross-examination

I was observing the care manager’s evidence: he was a witness for the applicant (the ICB). There was a clear lack of patience with him from some of the barristers, one of whom was cross-examining quite curtly. Some things written down look neutral, but when said in a harsh tone can be quite sharp: “I can’t hear you you’re going to have to speak up. // If you don’t know you don’t know – don’t guess”. I understand this tone – it is a strategy with witnesses to send a message to them – they mustn’t think they can squirm away from difficult questions – they must answer them and it’s a no-nonsense exchange. It didn’t feel inquisitorial though, but very adversarial – a bit like we were in the criminal courts, not the Court of Protection. That may be in part because this is a fact-finding hearing. And when you have institutional witnesses making allegations against family members, and you are for the family, I do understand that style of advocacy. But the problem was that it made the witness quite defensive. At one point the judge had to step in – “you are not on trial here“. After he did that, you could see the witness relax and get more confident in saying simply: “I don’t know”. This was really important, and after the judge said that, he less often said “I would have, I must have, etc.” and instead produced more precise recollections, or admitted he could not recall. I wondered what the value of more reassurance earlier on would have been, or a different style of questioning.

The grandmother, who was a litigant in person. also cross-examined the witness when I was watching. I always struggle with litigants in person cross-examining because it’s just so rarely ever fair. And unfairness makes me upset. This time I found it extremely moving – not for my usual reasons, but because she questioned clearly and with grace. The judge didn’t over-intervene, but tried to assist her to get to the point. And, yes, she did do that thing where in asking a question she was really making a submission – but frankly, so did the trained legal advocates. At the end, she made a really powerful point when questioning the use of the word “thriving” in G’s records, pushing back on the idea she was thriving both medically and emotionally. The judge even remarked on her having a gift for asking succinct questions. I think this was part kindness, but also part truth. I left the hearing in awe of her composure given the subject matter and the difficulty of the task.

3. The judge

Finally – the judge. You could tell he was interested in the humans at the centre of this case and their relationships. He made remarks about personalities, asked about the morale of the care staff in the centre of the case (“rock bottom“), and remarked that an outing arranged by the care staff with the family – I missed the occasion, perhaps a birthday? – was “one glimmer of light in an otherwise miserable case”. He was obviously concerned by the level of conflict in the case between the family and the care staff, in which clearly polarised positions have become entrenched.

I wouldn’t be surprised if the judge had in his mind a case of his from 2 years ago: Lancashire County Council v M and others (Lancashire Clinical Commissioning Group intervening) [2021] EWHC 2844 (Fam). This was a family court case but with similar entrenched conflict between professionals and family, in which the judge actually had the benefit of a psychologist report. Among other things, the psychologist (Dr Kate Hellin) explained that the high needs of the child, their complex care, the high stakes of life and death, the pressures on care resources (exacerbated by the Covid-19 pandemic) had all impacted the emotional climate. As a result, the system around the child, including professionals and parents, became

“… sensitised and inflamed. Feelings have run high and perspectives have become polarised and entrenched.[ M] and [F], individual professional staff and their organisations have become stuck in polarised beliefs about each other. It has become difficult for the parents and for professionals to respond moderately in ways that sooth rather than exacerbate the dynamic tensions between the different parts of the system.” (§16 Lancashire County Council v M and others (Lancashire Clinical Commissioning Group intervening) [2021] EWHC 2844 (Fam).)

In that case, the psychologist’s analysis did not apportion blame. It recommended therapeutic “system theory” intervention, and noted that the court as a neutral authority, had in fact “diluted the emotional intensity of the polarised ‘them and us’ dynamic which previously existed between the parents and the health/care providers”.

Given this is a fact-finding hearing, and there are live allegations still in play, I don’t know whether the court can have the same effect here, nor if it should if any of the allegations are found to be proven.

It is perhaps too early to be contemplating the court having a diluting effect on the conflict in this case. But I’m sure this judge, if he has the chance to and it is appropriate, will be more than willing to try.

5. Updates from the RCJ in-person from 27th and 28th July 2023

By John Harper (@JohnLHarper_)

I’m an Advocate at DAC Beachcroft and an aspiring barrister, interested in Court of Protection and hoping to build a practice in this area when at the Bar. I observed several days of this hearing in person in the Royal Courts of Justice.

Thursday 27th July 2023

- There was a transparency issue on Thursday. The fact that I observed in person meant that I knew that Hayden J was going to sit again at 5.30pm. This was not made clear to those observing remotely because Hayden J rose and left it to Ms Khalique and her team to sort out, as it was their witnesses that had to confirm they were able and happy to give evidence that evening. If I hadn’t overheard counsel arranging this, then – like those watching remotely for whom the court sound was muted – I would not have known the court was going to resume that evening, and would not have been able to update Celia and for word to be spread around via Twitter.

- The fact that Hayden J has consistently sat late in this hearing show his, and all parties’, unwavering commitment to keeping this hearing on track, undoubtedly mindful of the impact of this hearing on the family.

Friday 28th July 2023

- Before the hearing started, I noticed how courteously the parties treated each other. For example, I saw the parents speaking cordially with the representative of the Official Solicitor. This made clear to me that, even though each party comes to the hearing with a different perspective and aim, proceedings which about such serious and contentious issues can nevertheless be conducted amicably. This surely makes the whole experience a more positive one, or at least less negative.

- The examination-in-chief of G’s father was unusually lengthy. Hayden J granted Mr Patel 30 minutes, but it in fact lasted around an hour and a half. Most of this time was Mr Patel and Hayden J asking questions about the Father’s relationship with G and the contextual landscape on which this hearing lies. Although I imagine the reason for doing this was not for the benefit of those observing, it nevertheless proved to be so. While the Father passionately spoke about his daughter, I noticed that there was a distinct quiet in the courtroom. It seemed that the utmost respect was given to the Father to talk about his daughter uninterrupted and with everyone’s undivided attention.

- Another thing that struck me was how much Hayden J appeared to put his cards on the table. He admitted to the Father, who has recorded over 100 hours of his visits to G’s care home and the conversations he has had with staff, that he “cannot think of a single occasion when covert recordings have not damaged the case of the person who advances them”. Furthermore, he intervened quite heavily during Ms Khalique’s cross-examination, directly challenging the Father on the truth of what he was saying. For example, the Father spoke positively of the working relationship with hospital staff when G was a patient there prior to moving to the care home and Hayden J questioned him by saying that there was actually great deal of conflict there. The Father insisted that this was only towards the end. Hayden J disputed this and said the conflict lasted years. I think Hayden J’s interventions were useful because they showed the parents and their counsel the size of the hurdle they must overcome in order to prove their side of the story in this fact-finding hearing. This, possibly in a counter-intuitive way, levels the playing field in my view because the parties have more of an idea of Hayden J’s current position and the points on which he must be persuaded.

6. Reflections on facts, emotion, and the limits of collaborative care

By Tess Saunders

I am an assistant psychologist working within the Older Adult Psychology team. When my clinical supervisor, Dr Claire Martin (a member of the core team of the Open Justice Court of Protection Project) suggested that I come along with her to observe a hearing, I remember feeling a mixture of excitement and trepidation.

In my role as an assistant, I have had limited experience of legal issues within healthcare and I was extremely unsure of what to expect from the day. Claire explained to me that this was a fact-finding hearing, the purpose of which is for the judge to consider whether allegations made by the parties are true. Claire also reported that this case had been ongoing for a long period of time and she had observed previous hearings in which care home staff had given evidence. It was only then that the significance of this case began to dawn on me. My nerves only built when Claire informed me that I would be observing the cross-examination of P’s father. I didn’t imagine I would be able to observe such a notable part of a hearing and I felt extremely lucky to do so.

Having remotely observed a different hearing at First Avenue House a few days earlier, I had expected this hearing to be much the same. The judge was alone on the call in the previous hearing and the other parties were also attending remotely. However, in the current hearing on Friday the 6th of October 2023, the court met in person. Having never been into a courtroom before, remotely or in person, it reminded me only of a film set. I reflected that this ignorance of the justice system was likely indicative of my privileged position in society, having been fortunate enough to have never experienced the Court of Protection in a personal capacity before this exposure in a professional context. I was also surprised at the level of respect that the judge commanded. I had underestimated the strict power hierarchies which the court follows.

At the beginning of the hearing, I felt like I was trying to catch up with all the information that I had missed. Despite reading a blog post about the case so far (“Adjournment and interim judgment – Hayden J’s fact-finding hearing”), I felt like I had a lot to catch up on. The summaries that the barrister gave of the incidents they were focussing on helped me get up to speed.

During the hearing I was particularly struck by the sheer level of conflict between the family and the care home staff. Throughout the day the disputes between the two parties were evident, with the father referring repeatedly to “counter allegations” being waged between the groups. Working in mental health services, I have seen the value of collaborative working between families and care staff and I felt concerned about the implications of this conflict on P’s care. I believe that the best care results from joint working between families and carers to achieve shared goals, and it seemed hard to imagine that P was benefitting from this. The incident that Nageena Khalique KC (counsel for the ICB) raised, with the allegation that P’s father had tampered with P’s oxygen, particularly prompted these reflections for me. The atmosphere of suspicion between the care staff and P’s parents became apparent to me as this incident was described and I began to realise the extent of the barriers to collaborative care in this case.

This antagonism was further emphasised when a covert recording of an interaction between care staff and P’s parents was played to the court. In the formal and solemn environment of the courtroom, I found this recording extremely powerful and it emphasised to me the emotions behind this hearing. Working in psychology, I am familiar with people expressing their emotions, but in the court-room it appears that facts are given priority over feelings. For the purpose of the hearing this made complete sense, however I wondered how this felt for the P’s father during his cross-examination. I imagine it must have been extremely painful to relay the facts of these incidents without expressing the fear and anxiety that they must have evoked. I wondered what the impact of holding back these emotions might be on people giving evidence to the court and what the repercussions of this would be. I could only imagine that having to remain composed for the court would lead to a release of emotions later on.

In the recording, we heard care staff becoming frustrated at P’s parents for not leaving the unit and for “intimidating staff”. In my work in a children and young people’s service, I have experience of the parents and guardians of service users enacting behaviour which could be interpreted as threatening. Therefore,my first instinct was to feel empathetic for the care staff trying to complete their work in a challenging environment. However, on further reflection I considered the impact on P’s father of being labelled as ‘intimidating’. Might this limit his ability to raise concerns about P’s care or to ask questions about issues he does not fully understand? I was impressed by P’s father’s composure, both in the recording and during the hearing, and reflected that he is likely to be a strong advocate for his daughter and that this might be viewed as a threat by some care staff.

During the examination P’s father directly contradicted and denied the accounts given by nursing staff:

Nageena Khalique: … You hadn’t told the staff about this [the need for G to be suctioned] had you?

Father: No, that’s not correct.

NK: So that’s the difference.

Fa: On that day we were repeatedly asking staff for suction …

NK: Well let’s look back at the records for that day [found records – on view – read out notes, referred to meeting held between nursing team and family and that P needed monitoring.] You were recorded as asking throughout the shift but in fact [unclear] …. at that point you had not raised concerns to staff, that’s right – isn’t it?

Fa: No that’s not right.

It appears that a great rift has come between the family and staff and I wondered whether such a rupture in this relationship can possibly be repaired. At the end of the day’s observation, I was left feeling somewhat pessimistic about any resolution between the two parties.

This also emphasised to me the extremely difficult job facing Mr Justice Hayden to weigh up all the relevant, and often contradictory, information in this case and to process this into a coherent judgment. In terms of how Mr Justice Hayden managed the hearing, I admired the way he allowed P’s father space to explain his point of view and I was also particularly moved by his final words of the day: “I think it would be helpful if you enjoyed what may be our last weekend of sunshine this year and took some time off from this case”. I felt reassured that Mr Justice Hayden was considering the emotional and physical toll of participating in the court for all parties and encouraging them to take care of themselves.

My experience of observing this hearing has given me a new-found respect for the courts and the role they play in disentangling these complex situations about a vulnerable person’s care. This case has made me reflect on the power dynamics between service users, their families and care staff and consider the limits of collaborative care when these dynamics are in place.

7. The tables are turned: A litigant in person is cross – examined

By Anna (@AnnaJonesBrown)

She “is a litigant in person, a powerful advocate in her case, one of the most articulate lay persons I have heard in quite some time”. That’s what Mr Justice Hayden said about P’s nan (N) at the end of this day’s hearing, on Monday 9th October 2023.

I have blogged before about my experience of watching N cross-examine medical staff in this tragic case. I was very impressed with how she conducted herself. So, I wanted to see what would happen when she appeared in the witness box to be cross-examined herself. I was particularly interested because I had been a litigant in person in my mother’s COP case (and blogged about it here: “’Deprived of her liberty’: My experience of the court procedure for my mum”. I found it very stressful, despite the efforts of the legal professionals to put me at ease. But my situation was nowhere near as difficult as this case. N had the task of cross-examining witnesses and was now being cross-examined herself. And she was being accused of tampering with her granddaughter’s medical equipment. It should be stated that nobody is suggesting that she did this to cause her granddaughter harm. It seems to be clear to everybody that she cares deeply for her. The suggestion by staff at the care facility where G is being looked after is that she did this to make them seem incompetent, because the family are not happy with the placement, and want G to come home.

N was on the stand for over 2 hours on this day. She was cross-examined by Nageena Khalique KC, Counsel for the ICB, although the judge himself interjected very frequently (and will be further cross-examined by other Counsel at a future hearing). I noticed that something in her demeanour had changed since 21st July 2023, almost three months previously, when I had observed this case before. N retained her spirit under cross-examination, remained polite and respectful and clearly still fighting for what she believed was right. But she seemed less hopeful. More downhearted. Older. Sometimes she couldn’t hear. At one point she said “my eyes and ears aren’t what they were” as she asked Nageena Khalique KC to repeat a question. She also struggled occasionally to find the right document in the court bundle. This was a reminder that this litigant in person (LIP) was not a legally trained professional (as far as I know) but a family member who seemed to be post state retirement age. Maybe this change was due to the situation of being in the witness box rather than at the end of a computer line, as she had been for the previous hearing. And now she was the witness and didn’t know what questions were coming. And she was representing herself. I know from my own experience how much being involved in a COP case can impact a family, and it would be hard to argue against the view that, given the circumstances of this case, a family’s experience could be much harder. Maybe the change was because three months had passed without resolution, despite the urgency mentioned back in in July. And also, something had clearly happened the weekend before this hearing, which was referred to just after she had taken the oath.

She was asked by the judge whether there was anything she wished to say in addition to her witness statement. She replied that everything continues to happen, especially last weekend and it was traumatic for G. The judge reminded her that this hearing was a factual enquiry and that he was “not going to open that box at all”, that it was important she concentrated on herself. N replied that she was concerned for G’s safety and wellbeing. This exchange reflects the tone of the afternoon: N conveying how her primary concern was G’s safety and wellbeing and the judge focussing on gathering facts. This was, after all, a fact-finding hearing. The problem is that the facts are disputed.

In this blog I will focus on certain aspects of the cross-examination I observed:

- What I learned and discerned about N as a litigant in person

- How N feels about G

- N as a family member of a “P” in the Court of Protection

- The judge and counsel addressing N

The reason I have decided to focus on these aspects is that I want to get behind the type of person this LIP appeared to be, what came across as important to her as a family member and how I felt she was treated by the legal team.

N as a litigant in person

I had already formed a certain view of N from seeing her in the hearing back in July. In my eyes she had performed impressively as a LIP. I wondered who the person behind the litigator was. I learned a bit more about her background in this hearing. For example, at one point in the hearing, Nageena Khalique KC was reporting that staff felt undermined and how staff morale could be negatively affected because N stayed in the room when a staff member was training another staff member with an aspect of G’s care (hoisting). The judge was keen to understand whether N could see how staff could feel undermined in that situation. He asked N about her experience of training. She mentioned that she had been a UK training manager. She said that her motto had been “always catch them doing something right”. The judge also asked N how she would feel if she was the manager and this was her staff. She replied that she would feel as though she had let them down with their training and for the fact that they felt understaffed. These exchanges gave me an insight into the type of manager that N might have been, caring about her staff and wanting them to succeed. Not the type of manager that I have sometimes seen, who blame staff for mistakes and who don’t show them positive values.

The judge seemed to accept that N’s managerial experience meant that she could answer some in-depth questions about choices. He even said: “If you were a barrister, I would be asking….what the long-term options are”. He suggested to her that she was aware of resources and options, so what were her thoughts? At this point there was a glimpse of how exasperated she must have felt, because she replied that with the amount of resources the whole case had cost, G could have been home. I didn’t catch the judge’s reply but her response to him was “I didn’t mean to be disrespectful”. I should say that she didn’t become over-emotional at any point and this was one of the very rare times when her composure slipped slightly.

Another comment that revealed something of N’s character was when Nageena Khalique KC showed her a statement from a member of the medical team and the person had written something that N disagreed with. Counsel asked: “Do you agree that this statement is clear about how your presence in G’s room undermines the staff?” N replied: “Those are the words she has written down. I would not have said ‘are you calling me a liar’, I would have been more articulate.” And I could believe that she would have been.

After the glimpse of N as a manager, it was also very clear that N had spent a lot of time caring for G. She stated that she had been involved with G’s care for years, and had spent two days a week with her during the time that G had been in hospital. This demonstrated her dedication to G and in my eyes why she felt that what she had to say about G’s care should be listened to.

I don’t feel that many people could successfully challenge N’s knowledge of aspects of the case. At one point Counsel said that two nurses had separately said that they had checked the oxygen. Quick as a flash, N replied “I don’t believe that (X) is a nurse” (it seems she was a Health Care Assistant). Not only did she know this, but she was careful in her language, saying “I don’t believe” rather than “She isn’t”.

Counsel pursued a line of questioning leading N to consider how the oxygen could have come to be off when it was supposed to be on. Counsel suggested that there were only three possibilities:

- That there were repeated errors by different members of staff

- A rogue staff member

- G’s Dad or N had tampered with it.

Counsel asked N to agree that these were the only three options. At this point the judge noted these possibilities down and repeated them to N. Nobody came up with any other possibility. Counsel asked: “Can we discount a rogue member of staff as being highly unlikely?” N agreed. Counsel then suggested that it is extremely unlikely that it is (caused by) repeated errors by professional staff. N said that she didn’t agree, and that it could be an explanation. Counsel asked for confirmation: “you think there are multiple errors by different staff members?” N said, yes, it could be a common error in procedure. And she repeated something she had said earlier to the effect that ‘nobody ever saw me tamper with the oxygen, I was never alone in the room’.

N was also not frightened of voicing serious concerns about the evidence. When one of the observation documents had been shown on the screen, she mentioned that there was something about it that was troubling her. There was an empty space in the middle of a paragraph and then a side note, written by a staff member, about N and oxygen. The exchange was along these lines:

Counsel: “what are you suggesting?”

N: “I’m saying that it looks as if the note had been changed.

And:

Counsel: “Are you suggesting that’s not true?”

Nan: “That oxygen was off when I walked in the room”

The judge seemed shocked by this exchange: “Are you saying she is stitching you up?…It is a fabrication? This note, “suspiciously in the margin “ is a fabrication, untrue? A stitch up?”

N replied that it may be a defence by them (the staff).

The judge carried on: …. “but is therefore an attack on you? An extremely experienced nurse is fabricating evidence?”

N replied that it was the same nurse who swore in front of G she hated the family.

The judge will have to decide the facts about this episode. I noticed that N was examining each document very carefully. I could see how conscientiously she had prepared for her role as a Litigant in Person, and the preparation must have helped her in her role as a witness.

At one point, the judge questioned N about an account by a staff member. N replied by listing four members of the medical team, and saying that they all have different accounts, so which account is the true one? The judge replied by asking: “Well, if they are all against you, they aren’t getting their story straight, are they?” to which she replied instantly: “No, M’lord”.

How N feels about G

To my mind, anybody listening to N can tell that there is a real sense of urgency about this case and how it is resolved. Time is ticking on. And N clearly believes that the situation is worse now than it was in July for G.

At one point my notes say (N speaking): “My sole focus was keeping her safe, when you see her now, a shadow of her former self…..I’m petrified for her safety …..when I take her back she starts crying when I ring the bell…..she hates it there”.

Another exchange involved the judge getting N to concede that the staff cared for G and were trying to do their best by her. The exchange went along the lines of:

Judge: Do you remember that nurse, I can’t remember her name, who said, “when I see G, I see a woman of my own age, and I think “what would I like to be doing ?” What do you think?

N: The OS went to visit and they (the nurses) said they wanted to do a lot of things, like take her out shopping, take her to Blackpool. But in the last 12 months they haven’t done them. We’ve phoned and we say ‘what has G done today, has she sat up?’ and the answer is ‘no, she’s been in a bed all day’.

Counsel suggested that the medical staff were trying to help G, not harm her

Nan replied: “I have never accused anybody of doing anything on purpose.”

The judge then stated that it is “still your belief”.

N replied that she didn’t believe they were doing it “on purpose”, but were “negligent, and getting worse in terms of cleanliness”, and that couldn’t be in G’s best interests.

When asked what she feels G needs, she said, she needs the input of family, freedom to go into the community. “Her whole life is upside down”. And she should be moved to a place of safety with access to family (There is, of course, an injunction restricting the amount of time the family can spend with G.)

N as a family member of a ‘P” in the Court of Protection

N clearly feels that the family’s view and experiences have not been taken into account enough when decisions have been made about G, and what is in her best interests. This aspect really resonated with me, I must admit, even though there wasn’t as much at stake for us. My siblings and I felt that we had not been consulted enough as part of the s21A Deprivation of Liberty appeal that went to the COP. Decisions were being made by professionals who had very limited knowledge of my mum.

Counsel asked N whether she could approve of the new move (when she moved to her current placement after a number of years in hospital) “in a dispassionate way”. N replied that she had cared for G for years, including 2 days in hospital every week “and nobody consulted me at all”.

N also said that she was never consulted as to P’s care despite being a main carer. “I’ve read the Mental Capacity Act and it talks about consulting family and what should happen, least restrictive (etc).” She added: “she (G) was discharged without consulting with family”.

Counsel also asked her: Did that make it, do you think, difficult to accept anything that the staff suggested, and follow that request?

N replied: not if it was in G’s best interests. I found it hard when staff who didn’t know her said “don’t rub her tummy like that”. This particular insight into the intimate care N provided for G touched me.

One line of questioning that came up multiple times, from Counsel and the judge, was that N was questioning G’s care by experienced medical staff when she wasn’t medically qualified herself. For example, Counsel asked N if she believed her opinion was better than the clinicians? Nan replied: “yes, based on my experiences with G”. At one point, the judge pushed her on the fact that she has had no medical training, to which she replied, “I’m not medically trained but I can spot when things go wrong”. And at another time, Counsel stated that something was “a clear example of you refusing to accept the decision of a medically trained professional.”

The judge and counsel addressing N

I would like to end by making some observations on how Counsel and the judge treated N. Firstly, there was, of course, robust questioning of N by Nageena Khalique KC. She pushed N very hard. At times, to me, it felt almost like how I imagined a criminal court would be. But of course, I am a lay person. I’m not sure I would have handled the questioning as well as N did. She never lost her temper or seemed defensive. Towards the end of the cross-examination, Counsel persistently pushed N to admit that she challenged medical decisions, with an example of which hospital G should be admitted to when she fell ill and was in severe pain. N stated that she wasn’t challenging, she was asking questions. The exchange continued until Counsel stated: “you were challenging the decision because you thought you were right, rather than step back and let the staff do their job”. At which point, in her final words before the cross-examination ended and after a long day in court, N said “Yes, I did challenge the decision.”

As for the judge, I felt he was doing his best to understand N’s position, even if he didn’t agree with her. Some of the statements he made along the way were: “I’m trying to understand your beef”; “Why would she do that? I don’t understand Mrs N, I really don’t”

“Everybody wants the best for G, but we differ in our views”.

At one point, when N stated that “nobody has thought about the effect of this on G and on the family”, the judge reacted strongly: “I have ensured that people think about G.”

He seemed to me to be hinting that the family could have changed the way they acted in order to achieve their goals. For example, he said: “have you thought of other strategies?”and “Did it ever occur to you to suggest to {Father] that you should back off, let the medical staff get on ..?” This was around the issue of compromise and collaboration with medical staff.

The judge also stated: “Mrs N, sometimes when I listen to your evidence, you question professional decisions and there is never the slightest doubt in your voice that you are right”.

These last exchange did make me feel a little uneasy. Should a family have to “play the game’, adopt ‘strategie’s, if they are truly concerned for their loved one’s safety and well-being? Or is it just a necessary part of the fight? Clearly, for the family in this case, it is a question of life and death.

Conclusion

I am fully aware that I watched this cross-examination with the particular perspective of a family member who has acted as a Litigant in Person in a COP case, and that viewing the case through this lens influences how I see it.

At the heart of this case is a family who have cared for a loved one with multiple complex needs for much of her life, and on the other side there are trained and experienced medical professionals, who don’t have the same intimate knowledge of the patient they are looking after. Clearly the relationship between the two sides is irreconcilable. As the judge mentioned there has been a “colossal breakdown”. It is a bleak situation for G and her family.

As a family member of a P (protected party in the Court of Protection) myself, it is hard not to put myself into the shoes of the family. The judge will decide on the facts. I admire the way that N conducted herself. Towards the end, she said about P: “all her life it’s been a battle to get help”. In my opinion, N could not have fought any harder or behaved with more dignity in such very difficult circumstances.

8. Who are the ‘experts’ in G’s care? A care system and family at an impasse.

By Claire Martin (@DocCMartin)

A key aspect of the conflict in this case is about who has proper expertise in G’s care. Is it the family, who have cared for her – including delivering medical interventions for which they’ve been trained for her individually – for over 13 years? Or is it staff with professional qualifications and experience in G’s medical condition and treatments.

In this blog contribution, I reflect upon the positioning of ‘expertise’ in this case – the overall balance of which seems to reinforce professional over family expertise.

Where is ‘experience’ and ‘expertise’ located?

Mr Justice Hayden has published two previous judgments about this case: Re G [2021] EWCOP 69 and Re G [2022] EWCOP 25.

His judgments acknowledge “the huge input” (§57, [2021] EWCOP 69) this family makes into G’s care: she receives “devoted round the clock support and care from her parents” (§2, [2022] EWCOP 25). In the earlier judgment (but not the later one) he acknowledges the dedicated involvement and medical understanding of G’s father in particular. For example, he “is at the hospital every day, often early in the morning and participates in [G’s] medical care” (§47 [2021] EWCOP 69)and “his grasp of the medical issues of this case is impressive” (§43 [2021] EWCOP 69). The judge also notes that, since G’s father had taken over the care of G’s catheter in hospital, she had experienced ‘no further urinary infection’ (§48 [2021] EWCOP 69).

However, when I searched the two published judgments for the words “expert” and “experience(d)”, I found these terms always indexed the staff or other professionals and were never used with reference to the family.

The “experts” mentioned are “neurologists” (§12), and “Dr Andrew Bentley, a Consultant in Intensive Care and Respiratory medicine” (§25) – rather than the family (both quotes from [2021] EWCOP 69).

And people with “experience of G’s condition” are “the local hospital” (§19); Dr D “a Consultant in Respiratory Medicine and Clinical Lead for Ventilation at B NHS Trust” who “has over 25 years’ experience of managing long-term ventilation in the community and 12 years’ experience of dealing with tracheostomy ventilated patients involved in the transition from child to adult medicine”. The local hospital has “significant experience of G’s condition” (§19) and the carers at G’s current “experienced nursing home” (§67) “are all experienced with the techniques required in ventilatory support” (§52) (all quotes from [2022] EWCOP 25).

During the part of the hearing I observed on Friday 6th October 2023, when the Father was cross-examined, the expertise of the staff was continually highlighted.

Both Nageena Khalique (NK), counsel for the Integrated Care Board, who was cross-examining G’s father) and the judge, Hayden J, repeatedly referred to staff as ‘senior’ or ‘experienced’. For example (addressing G’s father): “a very experienced nurse with a long history of working in ICU” (NK); “extremely experienced nurse” (NK); “an incredibly senior doctor” (Judge); “a very senior experienced nurse” (Judge); “this undoubtedly experienced nurse” (Judge).

The following Monday (9th October 2023), Anna (author of the previous section of this blog post) observed the Grandmother (N) being cross-examined and she notes the emphasis placed on the expertise of “experienced medical staff” by contrast with the experience of the family members who aren’t medically qualified.

One line of questioning that came up multiple times, from Counsel and the judge, was that N was questioning G’s care by experienced medical staff when she wasn’t medically qualified herself. For example, Counsel asked N if she believed her opinion was better than the clinicians? Nan replied: “yes, based on my experiences with G”. At one point, the judge pushed her on the fact that she has had no medical training, to which she replied, “I’m not medically trained but I can spot when things go wrong”. And at another time, Counsel stated that something was “a clear example of you refusing to accept the decision of a medically trained professional.” (from Anna, above)

Later, on 17 October 2023, Jenny Kitzinger observed G’s mother giving evidence (and shared her notes with me) and again I saw the same pattern (e.g. addressing G’s mother: “You’d agree [nurse] is a highly experienced, qualified, excellent nurse at [care home]?” (NK))

I wondered why there was this repeated emphasis on the expertise and experience of the staff. Was it to position G’s father (in particular, since he takes a more active role in G’s medical care) as less experienced or less expert in the care of his daughter? Was it to indicate that the health care professionals were the ‘real experts’, above scrutiny and criticism due to their experience and seniority? Was it being suggested that senior and experienced professionals are unlikely to make mistakes in the care they provide?

Here are some examples:

Suction equipment

An incident had occurred which led G’s father to raise a concern that G’s tracheostomy suction equipment was not correctly set up.

NK: [There is] an allegation that staff failed to set up her suction. The evidence from [member of staff] … she gave a reasonable explanation that she left it in a sterile bag. You did not accept her clinical judgment and the reasons she gave, did you?

[The nursing notes were on view for the court – and observers – to see.]

Father: What we’d encountered …. it wasn’t just the final piece [of equipment]… what we’d always been told in our training … in an emergency, it would be too long. [I lost some parts of what P’s father was saying but the father is talking here about training that he and G’s family had received from the hospital where G had been an inpatient for thirteen years. He was expressing a view that the piece of equipment was not readily available – because it would need to be removed from the sterile bag before it could be used – and his belief from the training he’d been given was that it should have been removed already, in case of an emergency.]

NK: She’s a very experienced nurse with a long history of working in ICU (Intensive Care Units). She said the tube was next to bed and ready to go when needed, literally seconds …. You don’t accept that was a good clinical decision, do you?

Father: [Responded by describing more nuance to the incident than was being presented by the care home team]

Record Keeping

There was also an issue with the ‘authoritative’ (or otherwise) nature of care home records completed by the “experienced” professionals. The father repeatedly said that he did not accept the accuracy of the care home nursing records for when the family raised concerns.

On the day in question, for example, “we were repeatedly asking staff for suction’” he said. But Nageena Khalique showed several entries from care home records stating that the family had not raised this issue until around 5pm.

Judge: [Father’s name] you say that you had repeatedly mentioned the need for suction. Are you saying that on this occasion, despite your request …. there were no notes written up on those requests?

Father: Yes

…

Judge: You have accused an incredibly senior doctor … of dishonesty … a very senior experienced nurse of [lost] … you say the purpose … [lost].

Father: When I say she behaved dishonestly, was where she had planned discharge for two years without informing the family. That’s very different. [Referring here to a hospital consultant where P was a long-term inpatient, not a current doctor in P’s care]

(Later)

NK: Contemporaneous records on the day show this. I’m not going over that again with you [Mr – Father’s surname]. The second incident on [date] in relation to the safeguarding referral on the same day – we are still dealing with [nurse X] evidence – [Nurse X] is an extremely experienced nurse, [she is] fastidious in carrying out her checks. There is no reason that she would have missed [lost] ….. do you agree?

G’s father did not agree, and his evidence rested on what he described as repeated errors in G’s care, noticed and raised by the family, that he asserted he and his legal team had evidenced in the hearing.

Mother’s reliance on Father’s expertise [drawn from Jenny Kitzinger’s notes]

Judge (to mother): Is there anywhere in these statements where you’ve preferred the view of nurses or carers against [Father] and [Grandmother].

Mother: No.

NK: There’s a difference between being able to understand and use medical language and being a medical practitioner. [Grandmother] rates [Father’s] understanding of [G’s] medical needs up there and sometimes surpassing the knowledge of medics. Do you share this view?

Mother: [G] wouldn’t be here without [the] doctors and nurses.

…

NK: If [Father] with all his experience says X is better for [G], with all my experience … and a medical professional says ‘I hear what you are saying but actually I think Y is better’, whose opinion would you defer to?

Mother: I can’t answer that because I know there are times when we go with what the doctor says is right.

G’s mother expressed a view that one particular nurse at the care home ‘had it in for’G’s father, saying: “She felt threatened by his knowledge from day one – she felt intimidated by it”.

…

NK: You (?) interfered with equipment to paint a picture of highly experienced staff as incompetent.

Mother: No

NK: [reading from nursing notes: ‘Dad challenged … regarding decision not to get her in her chair. Staff didn’t think that appropriate as she’d only just got back from hospital’] Did you accept the clinical decision?

Mother: [explanation of why father was right and staff were wrong]

Judge: Just answer the question!

…

NK: You’d agree that [nurse] is a highly experienced, qualified, excellent nurse at [care home]?

Mother: That’s what they say, yes.

NK: Any reason to disagree with it?

Mother: That’s what they say [partly inaudible]

Judge: That just sounds childish and petulant [and judge then went on to underline nurse’s vast experience and expertise]

Mother: There are things she’s not told the truth about.

So, this is a family whose members insist on their own experience, skill and expertise in caring for their daughter. While accepting that G is dependent on medical care from doctors and nurses, they feel in a position to assess and to criticise the quality of that care, from their own knowledge base, and to point out errors.

While this may be an extreme example of such dynamics, tension or conflict between staff and the parents of children with complex needs seems very widespread.

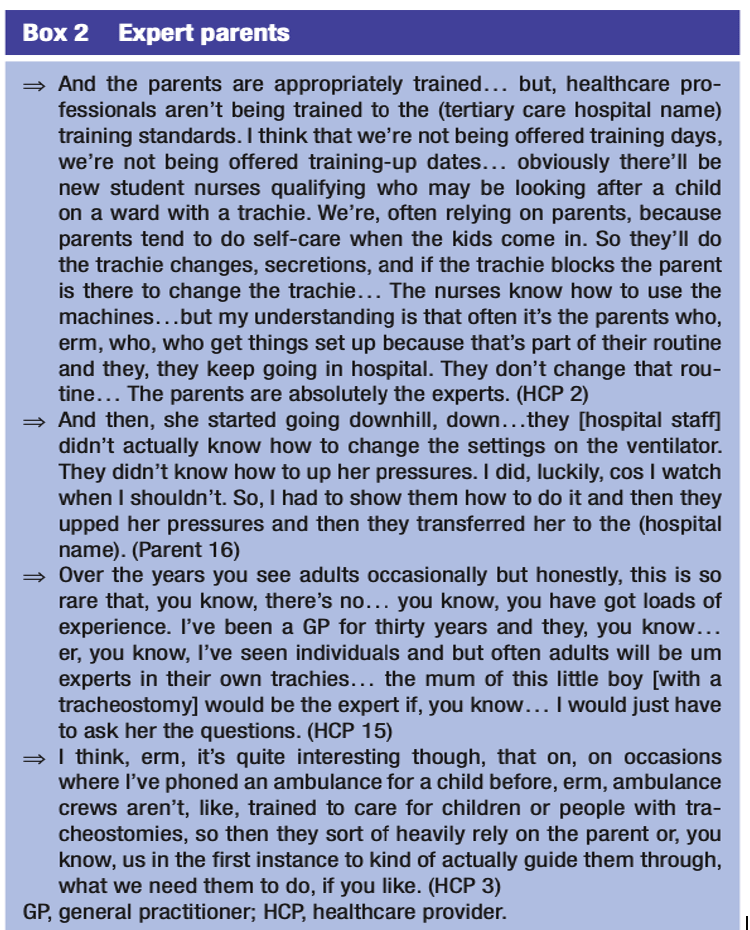

Research on parents of children with tracheostomies and complex needs shows that parents are properly considered ‘experts’

G in this case is now an adult. However, she was in hospital for 13 years, including during childhood and her parents moved their lives to be with her (she was in hospital nowhere near their original home) and her father (and mother) has been trained in her care. This seems not to be unusual in cases such as these. There is quite a lot of research about ‘expert parents’ and the experience of parents and professional teams needing to share their experience and care for children with these complex needs.

I have looked at three research papers, from 1984, 2001 and 2023.

“The experience of stress in parents of children hospitalised with long-term disabilities” by VE Hayes and JE Knox, 1984, Journal of Advanced Nursing 9(4): 33-41

“Negotiating lay and professional roles in the care of children with complex health care needs” by S Kirk 2001, Journal of Advanced Nursing 34(5): 593-602

“Providing care for children with tracheostomies: a qualitative interview study with parents and health professionals” by Hall N, Rousseau N, Hamilton DW, et al. . BMJ Open 2023;13:e065698

Depressingly, they all point to the same repeating tensions over the forty-year period.

The 1984 research shows how parents’ detailed understanding of their own child’s needs can come into conflict with that of ‘experts’:

Investigator: What you seem to be describing is that we ‘experts’ come in and tell you what to do, instead of asking you how you prepare your son? Parent IO: That’s right, I know this child. I know what he wants to know. Sometimes no matter what I say some nurses or doctors just won’t listen and I just realise — Oh forget it, it’s going to be another bad experience.’

The paper from 2001 explicitly refers to how parents (like G’s father in this case) are trained in the care of their own child to a very high level.

“Working with this group of parents was different for professionals because parents, rather than professionals, were often the experts in the child’s care. Not only did the parents possess an in-depth knowledge of their own child but they also had the formal knowledge gained from the training they that had received. Parents therefore both possessed and used this knowledge to assess and judge professionals’ level of expertise: ‘She done the opposite of everything that had been done and as soon as she went out the door, we had to rip it all off and do it again…. I didn’t like saying to her ‘You are doing that wrong’, to tell a nurse you are doing that wrong…she came the next day and she saw that we’d done it again…she took it all off, bathed it and she done it again her way…So in the end we just had say to her, ‘I think we’d best look after this’ (Mother of Christopher Cooper).” p7

And this, recent 2023 paper exploring the experience of both health care professionals and parents caring for children with tracheostomies reiterates earlier research that parents often become experts in their own children’s care. G’s father, in the hearing I observed, frequently referred to ‘training’ he had received from the hospital. This is echoed below in the interviews from parents and health care professionals:

I wonder how ‘expert’ in G’s care (in particular) the ‘senior’ and ‘experienced’ staff at the care home are? The HCPs’ quotes above would suggest that adequate training for staff, even otherwise very experienced staff, is often lacking, and that parents are often the ‘experts’ in their own child’s care. There is a seniority and experience to this parental role.

“Tracheostomies can be associated with potentially fatal risks such as airway obstruction, mucus plugging, tube displacement, bleeding and infection. Parents, professional healthcare providers (HCPs) and other carers must undergo a comprehensive training programme and competency assessments in order to manage required aspects of care, including providing suction, stoma care, tube changes and resuscitation. Training, knowledge and confidence in delivering this type of care can remain a challenge for parents and HCPs alike.”

Given the research indicating the precariousness and complexity of this kind of care, it seemed to me to be rather cavalier of the ICB (and the local Safeguarding Lead) to suggest that there are “normal things that are missed day to day”. Especially since their own protocols (discussed during the hearings) are for two members of staff to sign off a checklist that each step in G’s care has been completed. I might have misinterpreted the evidence – and perhaps things being missed regularly in this kind of care is usual and expected – but I can understand why the family might be vigilant to any such errors. I can also understand how a staff group might become exasperated by repeated ‘raising of concerns’ – though an alternative response to such concerns might be to trigger a review of skills to identify gaps in training.

Is there something else as well, though? Caring for someone is not just about tasks. This case, and the research, highlight the relational nature of such complex care. Health care staff need to have the interpersonal (as well as technical medical and nursing) skills and ability to see themselves as partners – colleagues almost – of parents who are trained in their relative’s very specific care. Professionals need to be able to accept that they might not always be the ‘expert’ (as would an ‘expert parent’ of course).

Throughout this hearing, I felt uncomfortable listening to the repeated statements about different professionals being ‘very experienced’ or ‘very senior’. The fact they are ‘experienced’ and ‘senior’ seems irrelevant to me. It felt as if seniority was being presented in order to exempt them from scrutiny or criticism, or to claim that it makes it unlikely that they will make mistakes. I don’t think that’s helpful to the professionals themselves. I understand that counsel for the ICB would be aiming to elicit admissions in cross-examination that would undermine the witnesses’ statements. I was surprised, though, that I observed the judge also emphasise (to P’s mother and father) the professionals’ expertise yet did not (in the hearings I observed in July 2023) emphasise the father’s expertise to the care home staff when they gave evidence.

Wherever ‘expertise’ lies in this case, what I observed in court led me to form the view that the relationshipbetween the family and the health care team as reached such a point of attrition that nothing the family does (or the health care team does) is viewed in good faith, and both sides ‘see’ only the errors of the other.

The family repeatedly stated that they regularly feared for P’s welfare (and this has been a feature described in previous judgments). Health care teams can be formidable for families. Though this family (in particular P’s father) was presented as ‘intimidating’ to staff, it is always important to remember that, no matter how we (professionals – and I include myself in this as an NHS worker) might feel, health care professionals have a lotmore power than families do. We have our ‘expertise’ to refer to, and organisations to back us up. Having to leave someone you love in the care of others is often difficult, even when things are working well. When you are terrified for their wellbeing (whether that is because of a view that the care being offered is inadequate or just due to the life-threatening nature of their condition, or even worse, both) it must be extremely difficult.

This is a family that has given up their lives and livelihood to be with G at the hospital, daily, for thirteen years. I think the ICB’s case rests on the suggestion that the family are so driven by their distrust of the care home’s skills, and that because the family is so knowledgeable about P’s care, they would somehow carefully calibrate interference withG’s equipment so as not to put her life at risk (e.g. knowing F would be okay on room air for a period of time) but to make the care home look incompetent, in the hope of achieving their goal for G to be allowed to live at home. Parishil Patel (for G’s father) had previously noted though, that there was always a staff member observing G, and no one had seen any family member tamper with her equipment. As an observer, I found my responses and inner questions see-sawing.