By Amanda Hill, formerly ‘Anna’ , 7th December 2023

This has been a long and difficult case, blogged about recently here). I’ve not observed a hearing in this case before – but I’ve read a blog about the previous committal hearing here.

In brief, at the previous committal hearing the judge determined that Mrs Liovbov Macpherson (Luba) had breached a court order by posting videos and other information relating to her daughter (P) on social media.

As a result, he’d imposed a custodial sentence of 28 days, suspended for 12 months.

Today’s hearing was the result of an application by Sunderland City Council to consider whether she had breached that order again.

This hearing only lasted for 10 minutes but it could not have been more dramatic.

I will first describe gaining access to the hearing, then describe what happened in the hearing, and finally end with some reflections about what I saw.

Gaining access to the hearing – using the new Video Hearings Service

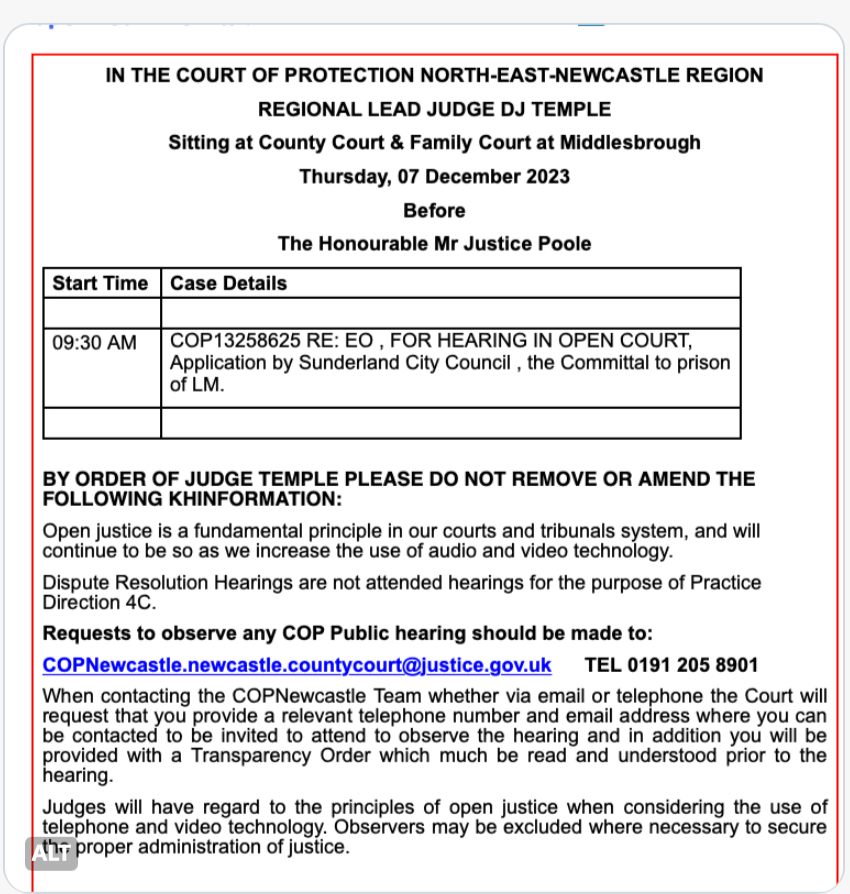

The hearing (COP 13258625) was listed as an in-person hearing at Middlesborough County Court at 9.30am on Thursday 7th December. It appeared on Court Serve as follows:

Normally if a person is a defendant in a committal hearing, their name should be listed in full. It is a fundamental principle of open justice that people should not face the risk of being sent to prison anonymously. This didn’t happen here – as you can see above, just the initials ‘LM’ are used.

Defendants are ordered to attend committal hearings in person – so the hearing was listed as an attended hearing. I don’t live in Middlesborough so I knew I would only be able to observe if a remote link became available. However, I saw the Open Justice Court of Protection Project post on X/Twitter, which said that a link might become available. So, I sent a request to observe to the court the evening before, just in case it was possible to observe remotely.

The hearing was scheduled to start at 9.30am and at 9.27am I received an email from the court with the Transparency Order (TO) explaining what I was and was not allowed to publish. It also said I would receive a link to observe the hearing as soon as possible. This made me optimistic that I would be able to observe.

However, at 9.46am I received another email saying, in summary, that a committal hearing must be attended in person so there would be no link. However, if the defendant was allowed to attend remotely then I would be sent a link to observe. I gathered from this that the defendant had asked to attend remotely and so I decided to wait. And I waited.

I don’t know at what point I would have given up waiting, as I didn’t necessarily expect to hear back from the court. But at 10.16am I received a standard email from HMCTS Video Hearings confirming the hearing and telling me that the hearing would start at 10.20am (so only 4 minutes later) and with instructions to sign into their website.

It turned out to be their new Video Hearings service (instead of MS Teams or Cloud Video Platform as usual) which – although I’ve watched a dozen or more hearings – I’ve never used before. It came in a separate email with a hearing link with my user name and password to log on to the site. I must admit I panicked a little bit as I was unfamiliar with the system and I only had 4 minutes to join. It wasn’t easy to do quickly. I had to automatically change the password and then there was a compulsory camera and microphone check. By the time I was admitted, it was 10.26am. I was relieved to see that the hearing hadn’t started and I was in a waiting room.

I was surprised and a bit worried that my camera and mike were automatically on (we are normally required to have them off when we observe hearings). But there was a “message video hearings officer” chat and a human at the other end (I assume) who helped reassure me that I could turn my camera off (which I did) and I would be able to mute myself when the hearing started. There was a screen informing me the hearing was about to start, so I waited again. I could see that Luba was connecting and disconnecting. I wondered how she felt about the joining process, given what was at stake for her. The screen then turned yellow saying the hearing was delayed.

Eventually, at 10.45am, the court room camera came on, pointing to the empty judge’s chair. I could hear some talking, and they mentioned that this was a new system to replace (I think) Cloud Video Platform. A clerk then spoke to me directly to ask me if I could see and hear, and I unmuted myself to confirm that I could. Then I switched my mike off and waited again.

At 10.52am Luba finally joined again and appeared on camera. I thought she seemed subdued and anxious, sometimes putting her head in her hands and drinking a lot of water. Her mike was on. She was alone and unrepresented. Two other observers joined the hearing.

At 10.57am the judge arrived and the court rose, nearly 90 minutes after the scheduled start time.

By 11.07am, 10 minutes later, it was all over and an arrest warrant had been issued for Luba.

The hearing

The only people who appeared on screen were Luba and the judge. It was slightly disconcerting to see Luba on screen twice – both on the video-platform itself, and on the judge’s screen as well. I imagined she could see herself too.

After asking the observers to let the judge know verbally if they had not received the TO (nobody spoke) for the vast majority of the short hearing, only Luba and the judge spoke. As they were the only people on camera, it almost felt as though I was watching a discussion between two people, rather than a formal hearing in a courtroom. This added to the intensity of proceedings. In other cases I have observed remotely, multiple cameras have been used and it’s been possible to see the barristers (and sometimes witnesses) in court as well.

This is a summary of what happened[1].

After informing Luba of the advocates who were in court but off camera, (Joseph O’Brien as a Litigation Friend for Luba’s daughter and Simon Garlick for the Local Authority), the judge asked Luba why she was not attending in person. She replied: “I have left the country for my own safety” and the judge asked her to tell him about that.

She said that she had left England because she was worried that she would be sent to prison for a crime she hadn’t committed or be put in a psychiatric hospital.

“Yes, there was an abduction attempt to put me in a psychiatric hospital. I made a report to police and your court but it was completely ignored and not investigated. Also, I know that I will be in prison for no crime committed, and this is the reasons I left England.”

The judge told her she was facing very serious charges and he didn’t understand why she wasn’t there in person.

She said that she had applied for political asylum and she couldn’t leave the country (she was in) because of that. She said she had been very badly treated in England and mentioned prison again. He asked if she was referring to the previous committal hearing and she confirmed this.

The judge replied that the committal proceedings were a lawful process and that she needed to attend to admit or deny a breach of the Order.

Luba said: “You are well aware I have been set up to fail. You have all the documents that show that from Dr Oliver Lewis, top barrister from Doughty Street.” (my note – Oliver Lewis represented Luba at the last committal hearing). “But you ignored all of the documents provided to you in regards to breaches of Art 6 (my note: the right to a fair trial) and the setup for fair, trauma-informed treatment. This is exactly what we’ve been victims of. You know that criminal solicitor that was appointed to me was set up. She sat at the hearing far away from me – and I could not hear what she was saying and at the end of hearing she said that I accepted that I had breached the Order. The orders are unsafe”

The judge said that he was not reopening the earlier committal hearing. He said it was alleged that she had reposted the original posts and links to the recordings that she had been given the suspended sentence for. “Yes, I did”, said Luba.

The judge said that by failing to attend court in person, and putting him in a situation where he decided to establish a video-link, she had caused disruption to other families who had important cases listed to appear before him that day. He gave her a choice: he would adjourn the hearing until the 19th December 2023 and she could appear in person, or “if you tell me you are not prepared to attend in person then I will issue a warrant for your arrest”.

Luba replied “Yes, but I have explained I have asked for political asylum. I have no passport, I cannot leave this country”. The judge said that she had provided “no evidence of that whatsoever”.

He asked again: “Will you attend on the 19th December?”

Luba replied that she was sorry, she could not: “I have applied for political asylum. I have no documents. I am stuck here now. I can attend via Zoom. That’s all”.

The judge then said in that case he was going to issue a warrant for her arrest “so that you will then be arrested and brought before the court since you choose not to bring yourself before the court”.

Luba asked “But how can you arrest me when I am out of the country and have sought political asylum?”

The judge replied that he had seen no evidence for that and that “it seems on the face of it an extremely eccentric position to take after living in England for so many years”.

Luba replied that she had submitted evidence to (I didn’t catch this word but it sounded like the name of an organisation) that she had left England because she had been “punished and persecuted for six years for no crime committed, just for trying to protect my daughter who has been badly treated and abused”.

The last few sentences got a bit confusing as the judge and Luba were talking over each other.

The judge said that all these matters “have been raised by you in previous hearings – appealed by you and dismissed, refused, as without merit” to which Luba retorted:

“The Court of Protection is a corrupt court”.

“You have on more than one occasion shown a dismissive attitude to the court and left me with no option”, said the judge. He asked counsel if they had anything to add and they said no.

The judge gave his final word. He was making an order for an arrest warrant for Luba and that concluded the hearing for today.

And with that the camera was switched off, for me – and for Luba too I imagine.

Reflections

I found this a difficult hearing to watch. It ended with a mother separated from her daughter, a mother who cannot return to England without being arrested. She feels that the system is failing her and she has been a victim. It’s not hard to see why she feels that way.

I know from my own experience (here) that it’s difficult for family members to navigate the Court of Protection, although my own experience was nowhere near as dreadful as this.

On one side, the courts applying the law as it stands and on the other a family member representing herself, in a foreign country, communicating in a language that is not her native language, fighting “the system”.

I believe that the Court of Protection works well when families feel that they have been listened to and treated fairly, whether they agree or disagree with the outcome. Luba clearly feels that that isn’t the case here.

I was struck by the judge using the word “eccentric”. He has previously used the word “bizarre” in another hearing. That made me feel slightly uncomfortable. Until one has been in the position of Luba, how could we know how we would act? It probably doesn’t feel eccentric to her. If she had acted differently, gone along with “the system” would the outcome have been different? Should families have to do that? And what about P, the person at the centre of this case? She is now, for many reasons, separated from her mother. As Celia Kitzinger wrote in her earlier blog, “This is a tragic and seemingly intractable case”.

Anna was the pseudonym of a woman whose mother was a P in a Court of Protection s.21A application. Since March 2025, Amanda Hill is allowed to reveal that she is Anna, because the Transparency Order covering her Mum’s case has been varied (changed). Amanda Hill is a PhD student at the School of Journalism, Media and Culture at Cardiff University. Her research focuses on the Court of Protection, exploring family experiences, media representations and social media activism. She is a core team member of OJCOP. She is also a daughter of a P in a Court of Protection case and has been a Litigant in Person. She is on LinkedIn (here), and also on X as (@AmandaAPHill) and on Bluesky (@AmandaAPHill.bsky.social).

[1] I don’t touch type and we are not allowed to record proceedings. I have captured as much as I could, given the speed at which I type

If there is a course available for family members of people detained under DoLS then why does the court of protection not inform them of this, surely this should only help to make their job easier.

LikeLike