By Claire Martin, 23rd June 2025

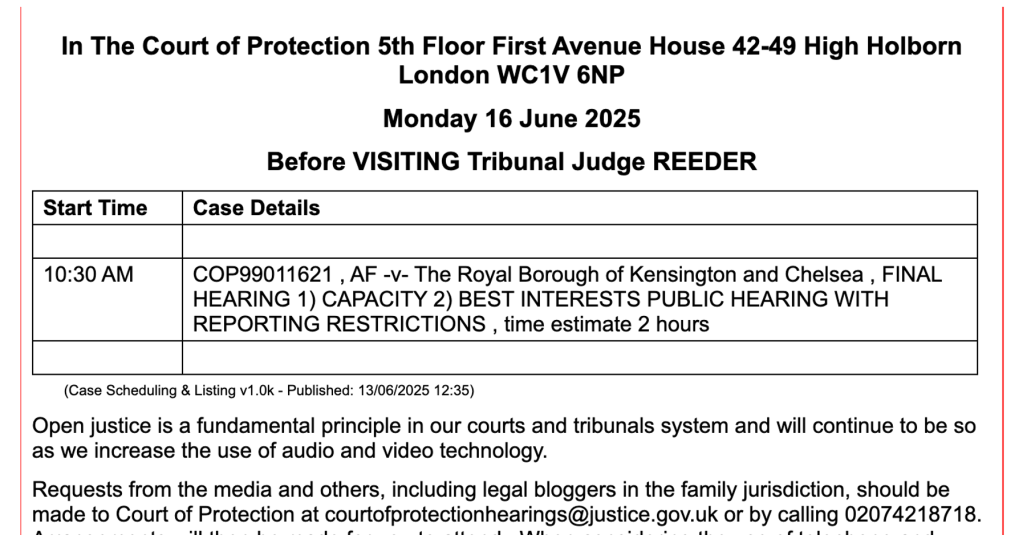

I had some unexpected time on Monday 16th June 2025, so I had a look at the listings the night before, and this one caught my eye because it said ‘FINAL HEARING’, so I knew that the judge’s determination on the matters listed (‘capacity and best interests’) was likely to be delivered.

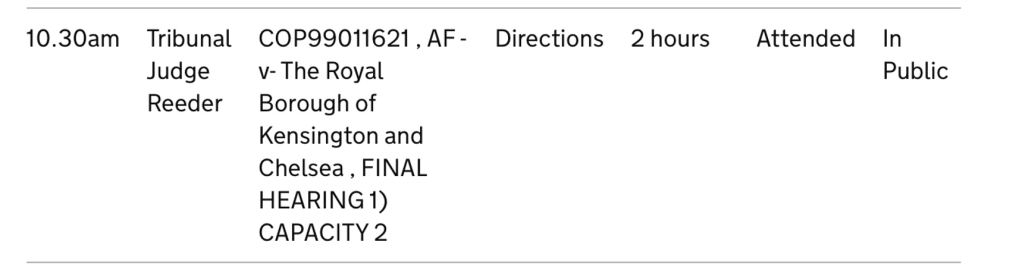

I asked for link – there was nothing in this list entry (from Courtserve) to tell me whether it was remote, hybrid or attended, so I just assumed there would be one. In fact, had I looked at the page for First Avenue House in London (as I did later), I would have seen that it stated that the hearing was “attended” – which usually means (and did in this case mean) “in person”.

Had I looked at the First Avenue House listings first, I might have felt deterred, but we’ve had many experiences of the court staff, if at all possible, providing a remote link for us, even for in-person hearings. And so it was for this particular hearing: COP 99011621 before Tribunal Judge Reeder.

I received the link to observe at 9.40am on the day of the hearing, along with the Transparency Order, which I had requested. I had also sent a message to the judge, via the court staff, requesting that the parties be permitted to share their Position Statements, which are very helpful to us as public observers because, as well as outlining the parties’ positions for the hearing, they often provide historical context to the case. In hearings where an opening introduction is not provided (contrary to the guidance), Position Statements often mean the difference between understanding and not understanding the case, making open justice more actual reality than mere aspiration.

The hearing start time came and went. I was waiting in the MS Teams ‘lobby’ and, getting a little worried that my tech might be at fault, I emailed the court to check whether it was starting late. The member of staff replied very quickly confirming the late start (thank you!) and just before the start time (of 10.51), I received both Position Statements from counsel for the parties (as requested of them by the judge). I really appreciated this – and the process was so much more efficient than (as is often the case) taking up time either during or after the hearing to address the request to share Position Statements.

Background to proceedings

The protected party (“AF” are the initials used for him in the listing) is a 78-year-old man currently living in a care home in London. He has lived there since November 2022. Up until that point he was living with his long-term partner who I will call X. In the hearing, she was described as his ‘common-law wife’. Prior to November 2022, AF assaulted X and was detained for four months under the Mental Health Act 1983. When he was discharged from hospital he went to live in the care home. He would prefer to be back living with X.

AF has several psychiatric diagnoses, for which he receives psychiatric medication including a depot injection of Haloperidol on a regular basis. There was some confusion in the hearing about whether AF is subject to a Community Treatment Order, and counsel for the Local Authority confirmed later that he is not.

In December 2023, a ‘standard authorisation’ was granted to deprive AF of his liberty in the care home. This included (I believe) not going out alone for his own safety. In May 2024, s21a proceedings were issued to challenge that. So, proceedings in this case have been live for just over a year. Subsequent authorisations for deprivation of AF’s liberty have been issued, pending the outcome of the case.

The remaining issues for the court to determine (as outlined in the LA’s Position Statement) are:

(a) Does AF lack capacity to make decisions about residence?

(b) Does AF lack capacity to make decisions about his care?

(c) Does AF lack capacity to make decisions about accessing the community?

(d) Does AF lack capacity to conduct these proceedings?

(e) Are the qualifying requirements for the standard authorisation met?

(f) What further best interests evidence is required, in the event the court concludes that AF

lacks capacity in the relevant domains?

Earlier in proceedings it had been determined that AF retains capacity to make decisions about sexual relations.

The Hearing

I found the hearing an instructive experience in how a judge works out, bit by bit, whether a protected party in the Court of Protection retains mental capacity for specific decisions, and how important that process can be.

This was a very routine s21a challenge for a P deprived of his liberty (in several ways, including where he lived, his freedom to go out alone and what care he received). There are very many such cases, most of which do not make it to the court. But what unfolded in the hearing made me think that everyone who is subject to a deprivation of their liberty needs a robust, independent eye (with authority to make change) on how those decisions are made in people’s ‘best interests’.

The protected party, AF, was at the hearing, represented by Kyle Squire (via his Accredited Legal Representative (ALR)). They were both sitting out of view on the remote link. I could see the judge, and Louise Thomson, who was representing the Local Authority (Royal Borough of Kensington & Chelsea).

When the hearing started, the judge spoke to me. I put on my camera and microphone. TJ Reeder confirmed with me that I had received and understood the Transparency Order. He also checked that I had received the Position Statements and reminded me that they are ‘unredacted’ (i.e. they hadn’t been anonymised) and that I should ensure that I look after them carefully (or words to that effect). I confirmed that I understood their confidential nature.

The judge then asked me if I was part of the Open Justice Court of Protection Project and when I said I was, he said ‘so you’ll be familiar with all of this’. At that, he asked me to turn off my camera and microphone.

Kyle Squire (KS), counsel for AF via his ALR, opened proceedings at the invitation of the judge:

KS: [I have the] observer in mind – shall I outline the issues?

Judge: Timewise – I am afraid we need to crack on. She has the Position Statements.

So, I had to quickly try to work out what was happening. I had only received the PSs about 5 minutes prior to the start of the hearing, but they were short, so I was able to bring myself up to speed.

There had been a jointly appointed expert witness (a Professor Afghan – I’ve not been able to find a website to link to so as to identify him) whose evidence had been questioned at a previous hearing [I think in May 2025] and he had been tasked by the court to complete a further assessment addressing specific questions (more on this later). He had completed this subsequent assessment via a remote meeting with AF [on 2nd June 2025].

Counsel for AF submitted that “the ALR on behalf of AF does not accept the conclusions of Professor Afghan […] Whilst we are grateful the expert has met with AF, it’s not a robust assessment. It does not meet with the statutory criteria”. Counsel went on to submit that Professor Afghan had not “set out what he relies on, it’s clear from the assessment narrative that the information considered is not the right information which was set out in the letter of instruction to him”.

So counsel for AF was clearly saying that the expert witness had not provided the ‘relevant information’ to AF on which to base his conclusions in the mental capacity assessment.

One example was the capacity assessment regarding residence decisions. Counsel for AF said that this had been done incorrectly. The expert (in his report) had said that AF had identified two options – to go back to live with X, or to stay where he is (or in the ‘general area’ in a care home). The expert is reported to go on in his report to “criticise AF for identifying [living with X] as an option. The point my instructing solicitor makes is that it’s not clear that AF knew that living with [X] was not an option”.

Counsel quoted from the expert’s report that AF demonstrated an ‘inconsistent expectation that he will be able to reside with [X]’, but that it was only on that day that it was known that X had informed parties that living back with her was not an option, and that it wasn’t clear whether the expert had shared that information with AF when he did the capacity assessment. Counsel submitted that the expert report did show that AF could understand, retain weigh and communicate the ‘relevant information’ provided by the LA about where he could live and what care he would need to receive, because he was able to say what ‘general area’ he would live in and talk about what care home would be able to provide the type of care he would need.

The judge said, “yes, he also consistently acknowledges that” [in relation to his care needs], going on to say that “it may be [Professor Afghan’s] conclusions are that he lacks capacity, but I need to see his workings out”.

I have heard judges say this before in relation to expert witness evidence, and Mr Justice Poole published guidance in a judgment in 2020, aimed at assisting experts to understand how best to assist the court when making and reporting capacity assessments. In this judgment Poole J states at §28:

‘”e. An expert report should not only state the expert’s opinions, but also explain the basis of each opinion. The court is unlikely to give weight to an opinion unless it knows on what evidence it was based, and what reasoning led to it being formed.

f. If an expert changes their opinion on capacity following re-assessment or otherwise, they ought to provide a full explanation of why their conclusion has changed.’ (§28 [2020] EWCOP 58]

Counsel for AF continued that Professor Afghan had failed to set out how AF’s reported lack of capacity is as a result of his diagnoses or ‘impairment of the mind or brain’ (the ‘causative nexus’), that the expert (in his report) “simply states ‘I have provided my rationale’, but it doesn’t come close to displacing the presumption of capacity”.

After counsel for AF made further submissions about the limitations of the capacity assessment, the judge then said:

“How does … in the ALR’s view … what’s the position of squaring this report with the EARLIER report of 24th February. It is striking that they are entirely opposite?”

It transpired that Professor Afghan, in February 2025 had assessed AF as having capacity for all relevant decisions, and then assessing AF as lacking capacity for all relevant decisions, save for contact with others.

The Position Statement for AF shows the stark change in the short space of time:

‘Capacity

6. The court now has two reports from Prof Afghan, the single joint expert psychiatrist in these proceedings. The court will be aware that in the first, dated 24 February 2025 the expert concluded that AF:

(a) Has capacity to make decisions about his residence;

(b) Has capacity to make decisions about his care;

(c) Has capacity to decide to have unescorted community access;

(d) Has capacity to made decisions about his contact with others, including [X];

(e) Has capacity to engage in sexual relations;

(f) Has capacity to conduct proceedings.

7. In his addendum report, dated 3 June 2025, the expert concluded that [AF]:

(a) Lacks capacity to make decisions about his residence;

(b) Lacks capacity to make decisions about his care;

(c) Lacks capacity to decide to have unescorted community access;

(d) Has capacity to made decisions about his contact with others, including [X];

(e) Capacity to engage in sexual relations was not reassessed;

(f) Lacks capacity to conduct proceedings.’

Counsel for AF said that the ALR regarded this as a “complete volte face […] without explaining why”.

Of course, under the MCA 2005, capacity is time and decision specific, so it could be the case that AF’s capacity had changed between those two time periods. However, counsel for AF strongly advanced the position that the expert’s evidence did not “soundly apply the statutory principles and tests, and [that] the conclusions are not robustly reasoned”.

I wondered what the Local Authority position was going to be in relation to the ‘volte face’ in the expert’s evidence.

The following exchange between TJ Reeder and counsel for the LA (LT) was interesting:

LT: As you have seen [the] Local Authority’s view is that AF lacks capacity to make the decisions and accepts there are some areas where he DOES have capacity, but in relation to these decisions, residence and care, our submission is that he lacks …

J: How do you square that [with the expert’s change of evidence]? […] Professor Afghan has had two opportunities to report to court and one opportunity to explain and assist in relation to some misgivings about understanding his methodology in first report. […] So really what I could do with help on is how I square that Professor Afghan provides two reports in a short timetable and comes to different conclusions in relation to key matters (residence and care). In the first report … one of the things that was striking was that AF got full marks on the mini-ACE [a 30-point cognitive screening test that is a short form of the Addenbrooke’s Cognitive Examination, covering the domains if attention, memory, verbal fluency and clock drawing] and in the second [report, there was] no evidence that [he had deteriorated]. […] I need the workings, especially when he reaches entirely different conclusions. I am struggling, with your submissions as to why Professor Afghan’s second report is evidential … notwithstanding that he gives the opposite conclusions to his first report.

LT: He did the addendum [second report] AFTER hearing what was required of him.

J: Help me with residence and care. It is quite striking that we go from ‘has capacity’ to ‘lacks capacity’.

LT: Yes it is

J: I’d expect that to be explained, the change of opinion.

Counsel for the LA said that a second assessor, a (Social Worker) DoLS (Deprivation of Liberty Safeguard) assessor, also deemed AF to lack the capacity to decide on where he lives, at around the same time and that AF had given different responses in relation to returning home to live with X.

It was interesting to me observing the judge tease out the reasoning for submissions – to help him to weigh the evidence to make a decision. He was finding it hard to follow a logical path to a determination of incapacity for the decisions at hand. The judge said – multiple times – “I am struggling to understand”.

The judge decided to examine the DoLS form that counsel for the LA had just referenced:

J: Let’s look at the DOLs form, at the moment I am not impressed with Professor Afghan’s report and no one has yet been able to explain to me how one goes from capacity to no capacity in such a short space of time.

LT: It [the DoLS form] does state what the relevant information is […] and at the bottom of that box, when [he was] asked to ‘repeat to me what we have discussed’, he mentions when he can go out on his own, where he is living and not much else.

J: Yep, what significance is that?

LT: It’s expressing recall of the conversation they had had and information relevant to the decision.

J: [quoting from the DoLS form] ‘I asked him to repeat what we’d discussed ….. going out, where [he is] living, care…’ What else would they have discussed?

That’s [the judge is explaining that it is too high a bar to expect more recall]. I’m not sure, that’s how a functional thought process works, isn’t it? He’s repeated the headlines – has he missed any? He doesn’t appear to have done?

LT: No. He’s repeated the headlines and doesn’t appear to have missed any.I take your point.

J: So, his lack of capacity is [reported to be] based on being unable to understand the relevant information, and [being] unable to retain it. What’s he unable to understand?

LT: What he’s saying in the paragraph I just took you to, but you didn’t agree.

J: Which is what?

LT: I understand. I just refer to the information at the top, saying he’s not able to understand the relevant information.

J: It’s the workings. What IS IT he’s not understanding? I am struggling.

Counsel for the LA didn’t respond to that question.

J: Again, it’s wrapped up in these statements which could suggest a degree of insight. He’s asked if he can come and go: he says ‘Yes, but traffic is an issue’. Again, context is important, [he’s showing] awareness. […] There are two occasions where he wants to prove himself but acknowledges it’s busy and that he needs help. The retention point is just due to limited cognitive ability. Where can I find the workings for that? […] Look somebody needs to help me. You say that this is evidence that AF lacks capacity for residence and care. Can you help me with the workings?

LT: I can’t.

So, the Local Authority’s position was that the court should accept the expert witness’s evidence that AF lacked capacity for the decisions in question. And the judge could not discern the evidence to back up this position.

The judge asked counsel for AF the ALR view about the DoLS form:

KS: I would simply say that the reasoning is simply not sufficient to conclude that the presumption is rebutted. The rationale is not there. Some of the points […] don’t make sense. It’s surprising the assessor is able to conclude that AF is unable to retain ‘due to limited intellectual ability’ … AF is not someone who lacks intellectual ability in my submission.

Whether or not AF ‘lacks intellectual ability’, Section 2 (3) of the Mental Capacity Act 2005 makes clear that:

‘A lack of capacity cannot be established merely by reference to—

- (a) a person’s age or appearance, or

- (b) a condition of his, or an aspect of his behaviour, which might lead others to make unjustified assumptions about his capacity.’

At the start of the hearing counsel for AF had suggested instructing a further expert. The judge later returned to this proposal:

J: Does the ALR have any [further] submissions on that?

KS: Erm …. Yes it’s difficult

J: What do you say I should determine or direct today?

KS: First of all, I’d invite you determine that the evidence of Professor Afghan is not sufficient to displace the presumption of capacity, for all the reasons we have discussed.

J: So why should I pause for further evidence? Isn’t your submission that we should discharge the authorisation?

KS: Yes erm…

J: Doesn’t it follow?

KS: Yes it does, yes I think that has to be right. The opportunities have been given to [Professor Afghan]. In my submission then, the qualifying requirement isn’t met and the opportunity to terminate should be given.

J: I need to be clear that this is the ALR’s position. If you need to make a phone call then do.

KS: Yes I think I need to.

The position of the ALR was not clear and counsel needed a break to take instruction. And the position of the LA was:

LT: If you are of the view that you not able to determine he lacks capacity TODAY,

we would say we need further evidence [from a new expert witness].

At this point Professor Afghan joined the link. The judge informed him that the court was having a short break and to return in ten minutes. When the court reconvened, the judge checked with both counsel and agreed that the expert’s attendance was not required.

The position of the ALR was now clear: “The ALR says that the standard authorisation should be discharged today. There has been ample opportunity for the LA to discharge that burden [of proof to displace the presumption of capacity] and they have not done so at this point, and they are unlikely to do so speedily”.

And the position of the LA, also shifting from the start when it said to accept the expert’s evidence, was that the LA’s view now was that “Professor Afghan’s assessment and the DoLS assessment […] that there’s no workings out. We would seek further assessment. We wouldn’t seek discharge”.

The judge made a swift ex tempore judgment:

“Am going to make a short judgment which I will speak. […]. The gist of this is that my determination [is that] there is insufficient evidential […] [a] compelling body of evidence to discharge the statutory presumption [of capacity]… that means I am not satisfied that you lack capacity.

At this point I heard AF say, “Does that mean I am off the hook?”

The judge said he would explain in more detail:

“Between February and June 2025, [dates of] those two reports, nobody has suggested that there has been a material change in AF’s presentation [or] his functional abilities.

One therefore looks quite carefully for the reasoning for the reversal of an expert’s opinion from capacity to lack of capacity. What is apparent between the exchanges between counsel is that it is impossible to find adequate reasoning for the change in opinion.”

“I am asked to consider by the LA the parties putting their heads together to find yet another expert to assess AF. It seems to me [that would be] inappropriate case management and an interference with AF’s rights.”

“It seems to me the only proper course of action available is to exercise the power under s21a. The court orders – directs – the supervisory body [the LA] to terminate the standard authorisation in force”

At the very end of the hearing P spoke again:

J: That’s my decision. [AF] I wish you well

P: [What’s the] long and short?

J: My decision is that there is not enough evidence for me to say the court makes decisions for you. You can make decisions yourself. Please work with people at the [care home] and your social work team.

P: I can go out on my own?

J: The court’s not making any restrictions on that. Be sensible about it. You’ve not been out on your own for a long time .. yeah… ‘getting back on your feet’ as you called it. As I said, you have the benefit of a skilled social work team and the people at the [care home] struck me as lovely. You don’t have to listen to me any more!

Reflections

AF was quiet throughout this hearing. He made a few interjections, but I was struck by how much he didn’t intervene, given what transpired in the proceedings. I felt quite astounded on his behalf that there seemed to be no reasoning provided by the expert for the stark change in the assessment of AF’s capacity to make these important decisions in his life. How could this happen?

Then I thought: what if AF does in fact lack the capacity to make these decisions for himself and his best interests have not been served? The court seems to have been badly served in this case. Reflecting on some of the hearings I have observed over the past five years in the Court of Protection, and the detail and care with which capacity assessments are often conducted, I know that robust judicial determinations can be made, based on good evidence. All decisions in the Court of Protection – I think – are difficult. All judgments involve people (the assessors, health professionals, judges) – who do not know, or know well, the person at the centre of the case – making important recommendations and decisions about their life.

This case concerned me because, despite the capacity assessments not providing adequate rationale for the conclusions (of lack of capacity in many areas), the Local Authority’s submissions were to accept those assessments as adequate evidence. I found myself wondering how they had reached the conclusion themselves to make those submissions, given that the judge clearly ‘struggled’ throughout the hearing to make logical sense of the two assessments. How often are capacity assessment reports accepted without question, when people’s lives do not come to court? I was relieved to observe the judge scrutinise the capacity assessment process to the degree that he did, but alarmed that the expert report was so poor.

For now, AF is ‘off the hook’ – but possibly at risk if in fact a better report, properly conducted, would have established that he does in fact lack the requisite decision-making capacity.

Claire Martin is a Consultant Clinical Psychologist, Cumbria, Northumberland, Tyne and Wear NHS Foundation Trust, Older People’s Clinical Psychology Department, Gateshead. She is a member of the core team of the Open Justice Court of Protection Project and has published dozens of blog posts for the Project about hearings she’s observed (e.g. here and here). She is on X as @DocCMartin, on LinkedIn and on BlueSky as @doccmartin.bsky.social

This is really interesting, and a great blog. Thanks Claire!

LikeLike

Anyone instructed as an ‘Expert’ MCA assessor must have a robust working knowledge of the MCA and related case law to fulfil their duty.

Having a specific professional title does not equate to MCA literacy. In the case the ‘Expert’ overlooked the basic MCA principles.

Being clear about the relevant information to the decision, and trying to support the person to consider that information; is the foundation to a legally valid MCA.

If that isn’t visible in the report, the assessment can, and should be challenged.

The MCA is NOT a medical or cognitive test. Medical expertise may be helpful in some cases, but if the assessor does not apply the law, the MCA is not worth the paper it is printed on (let alone the expert fees charged!)

Thank you Claire, for a very thought provoking blog.

LikeLike

A brilliant blog, Claire, whicih bring so many critical points to mind.

The opinion is the proverbial tip of the iceberg. The justification, the formulation and the evidence to back these up are critical and take up the majority of the report (and time beyond the assessment meeting itself). If the evidence and rationale are not present or clearly stated, the report is not defensible. It’s as simple as that. I always think back to my high school days when my maths teacher wrote on my work (in red biro of course) “Show your workings”. You may arrive at an answer, and it may be the correct or an appropriate one, but it’s no use unless you can show how you got there.

This case also makes me think about the importance of ‘experts’ and those of us that carry out this sort of work in being aware of our limitations, maintaining compliance and keeping up to date. This was another thing that was drummed into me as I went through my clinical training. Regardless of professional title or qualifation, an expert should not agree to a piece of work for which they feel they lack the relevant knowledge or experience. To take on an assessment for which you are not appropriately qualified is, in my view, negligent and highly unprofessional. It’s not fair on the parties involved, to yourself and to your profession.

LikeLike