By Amanda Hill, 24th June 2024

“But in America, in my home, they are persecuting people for using their right to free speech and voicing their dissent. This is happening now.” (Bruce Springsteen, during his concert at Lille, Saturday 24 May 2025[1])

As well as saying people are persecuted for using their right to free speech, Bruce Springsteen also said that America is corrupt, and that democracy is dead there. I’m sure a lot of people agree with him (and a lot of people don’t) but I doubt that many people would question his capacity to litigate, because he expresses those views.

I didn’t expect to be sitting at a Bruce Springsteen concert and thinking about Lioubov (Luba) Macpherson[2] – a litigant (and recently also a protected party) in the Court of Protection. But hearing what he had to say made me think about beliefs, free speech and the capacity to conduct legal proceedings.

Two days before the concert, on Thursday 22nd May 2025, I had observed the last ten minutes of Mrs Justice Theis handing down her judgment in Luba’s case (COP 13258625), which we’ve been following, and reporting on, for some time. Theis J’s judgment concerns whether Luba had capacity to conduct contempt proceedings on 22nd January 2024 (contempt of court proceedings that resulted in a prison sentence) and whether she has capacity now to conduct an upcoming appeal against the judge’s decision to commit her to prison as the outcome of those proceedings. On 22nd May 2025, Theis J decided that Luba does have litigation capacity now for the upcoming Court of Appeal case, and that she had capacity to litigate in the Court of Protection back then as a litigant in person in a committal hearing too.

The published judgment, Macpherson v Sunderland City Council [2025] EWCOP 18 (T3) is clear that Ms Macpherson holds “strongly held beliefs” that affect how she conducts litigation but that this “does not equate with lack of capacity on its own” (§56).

Luba has been concerned with Court of Protection proceedings in one way or another for several years. In this blog post, I’ll start by setting out a brief “Background” to the case before writing about the four hearings I’ve observed concerning Luba’s capacity to conduct proceedings:

- The Court of Appeal hearing of 3rd December 2024: before Lady Justice King, Lady Justice Asplin and Lord Justice Birss between Lioubov Macpherson (Defendant / Appellant) and Sunderland City Council (Claimant / Respondent). The judgment can be found here: Macpherson v Sunderland City Council [2024] EWCA Civ 1579, with Oliver Lewis and Beth Grossman (instructed by Burke Niazi Solicitors) for the Appellant, and Sam Karim KC and Sophie Hurst (instructed by EMG Solicitors) for the Respondent

- The Court of Protection hearing of 18th February 2025: before Theis J, between Lioubov Macpherson (By her litigation friend, the Official Solicitor) (Appellant) and Sunderland City Council (Respondent) with Oliver Lewis and Beth Grossman (instructed by Burke Niazi Solicitors) for the Appellant, and Sam Karim KC and Sophie Hurst (instructed by EMG Solicitors) for the Respondent

- The Court of Protection hearing of 30th April 2025: before Theis J between Lioubov Macpherson (By her litigation friend, the Official Solicitor) (Appellant) and Sunderland City Council (Respondent) with Oliver Lewis and Beth Grossman (instructed by Burke Niazi Solicitors) for the Appellant and Sam Karim KC and Sophie Hurst (instructed by EMG Solicitors) for the Respondent

- Handing down of the judgment (from 18th February and 30th April hearings), in open court on 22nd May 2025: by Theis J. The judgment is here: Macpherson v Sunderland City Council [2025] EWCOP 18 (T3).

I’ll end with some “Reflections” on the case.

Background

Luba Macpherson has been involved as a party (sometimes as a litigant in person, sometimes with legal representation) in a long-running Court of Protection case concerning her daughter, referred to as “FP” in the judgments, who has been diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia. Luba’s daughter lives in a care home and Luba believes she is being abused and is being given medication that is making her symptoms worse. She has regularly communicated her views on these matters to her daughter, with the result that the court has authorised various forms of contact restrictions (and at times a total ban on contact). More detail is available in a published judgment (SCC v FP and others [2022] EWCOP 30) and in a previous blog about this case: An ‘impasse’ on face-to-face contact between mother and daughter.

The case concerning her daughter is now concluded. Luba appealed the decision and the appeal was dismissed. There is no further recourse for the substantive proceedings to be re-opened.

During the proceedings concerning Luba’s daughter, the Court of Protection judge, Poole J, made an injunction prohibiting Luba from posting material about FP on the internet. He said:

“The purpose of preventing the Defendant from posting films of her daughter and naming her through posts on social media platforms, is to protect FP. Not only is it a gross invasion of FP’s privacy to do so but, in this particular case, the nature of the Defendant’s publications about FP is to create the wholly misleading impression that FP is being abused and “tortured” by those caring for her, as sanctioned by a “corrupt” court system.” (§30 Sunderland City Council v Macpherson [2023] EWCOP 3

After Poole J made this injunction, Luba continued to post material about FP on the internet (she still does). Her rationale for breaching the injunction is that the court is engaged in a cover-up. She says she wants “ to show the distress that my daughter suffers daily, because so-called professionals keep my daughter in deliberately induced illnesses to suit the agenda that she lacks mental capacity“. (from Sunderland City Council v Lioubov Macpherson [2023] EWCOP 3).) She has “hundreds of videos to show the degree of distress and deplorable care, but it has been completely ignored by the Court and by the Regulators. This is why I have posted some of the videos on the Internet, just out of desperation”. From Luba’s perspective, the judge has ordered her to “delete material evidence” about her daughter’s deplorable care, and she is determined to expose it (see: “ An ‘impasse’ on face-to-face contact between mother and daughter”).

In January 2023, Poole J found Luba in contempt of court for having breached his injunctions by posting material about her daughter online. The judge imposed a suspended 28-day sentence (judgment here ([2023] EWCOP 3). ) We’ve also blogged about it: “A committal hearing to send P’s mother to prison”).

Luba appealed against this 28-day suspended sentence. Her case was heard on 4th May 2023 before Lord Justice Peter Jackson, Lord Justice Dingemans and Lady Justice Elisabeth Laing, in person, in the Court of Appeal (and there’s a published judgment here: [2023] EWCA Civ 574). Celia Kitzinger attended the hearing, at which, she said, Luba delivered a passionate, articulate and searing oral submission. Luba has subsequently published the text of this speech on her Facebook page, and it’s reproduced in an Appendix to this blog post to provide additional background to the case from Luba’s perspective. It’s important in explaining why Luba disregarded Poole J’s orders, even knowing she risked a prison sentence. Her 4th May appeal was dismissed.

After having received a suspended 28-day sentence, and after her appeal against it was dismissed, Luba continued to post videos and other material about her daughter. The local authority issued fresh committal proceedings – although by now Luba had relocated to France, where she was outside the jurisdiction of the court. Since Luba declined to return to the UK for the contempt hearing, the judge made a warrant for her arrest. At a hearing on 22nd January 2024 (which Luba attended remotely from France), Poole J imposed an immediate 3-month sentence for the new breaches, plus the 28-day sentence from January 2023, making a total of 4 months of imprisonment. We blogged about that hearing too: “Warrant for arrest of P’s mother”).

Luba wants to appeal that judgment (sending her to prison for 4 months) in the Court of Appeal. She filed her application to appeal a long time ago, on 21st March 2024, but it’s still not been heard. First there was a delay in securing legal aid, and then a delay due to a failed attempt to secure a transcript of the committal hearing. Most recently, the appeal has stalled altogether due to Luba’s own legal team having raised concerns that their client lacks capacity to litigate. So, it is now more than 14 months since Luba issued her application to appeal, and still it hasn’t been heard. We expect the appeal to be heard before the court term ends on 30th July 2025, and will alert readers (via social media and our “Featured Hearings” page) when we know the date for the hearing – as we’re sure Luba will on social media too.

I pick up the story from 3rd December 2024, when Luba’s appeal against her custodial sentence first came before the Court of Appeal – only to be sent back to the Court of Protection (before Theis J) for determination of her litigation capacity. As I outline above, that issue has now been resolved: the judge finds (on the balance of probabilities) that Luba does have capacity to conduct legal proceedings (both the earlier committal proceedings, and the upcoming appeal).

Why did Luba’s ‘strongly held beliefs” lead the Court of Appeal to make an interim declaration that she lacked litigation capacity? And how did the court reach a decision? Here’s what happened at the four most recent hearings relating to this matter.

- The Court of Appeal hearing 3rd December 2024: Court makes interim finding of Luba’s lack of capacity to litigate proceedings

The hearing on 3rd December 2024 was listed as Luba’s appeal against the custodial sentence imposed by Poole J almost a year earlier (on 22nd January 2024). I watched it remotely and when I logged on, two counsel were in the physical courtroom: Oliver Lewis, originally counsel representing Luba; and Sam Karim KC representing Sunderland City Council, the public body which had made the committal application, alleging that Luba had breached the judge’s orders. Luba attended the hearing remotely, via a video-link (she was still in France and subject to the arrest warrant).

It was clear from the start of the hearing that there was a problem. It transpired that Luba’s legal team had doubts about her capacity to instruct them in this appeal and had brought this to the attention of the court in advance of this hearing. The court had authorised an expert assessment of Luba’s capacity to conduct the proceedings – a paper-based exercise, as Luba had (not surprisingly) declined to meet with the psychiatrist. The psychiatric report had reinforced those concerns about Luba’s capacity, so she was now deemed a (potential) “protected party”. The CoA hearing was for the court to decide what to do, given that situation.

The hearing opened with a statement from Lady Justice King to those of us observing that there was a reporting restriction order in place to protect FP’s identity[3]. She went on to say that even though Luba was now also a (potential) “protected party”, as someone who may lack capacity to conduct proceedings, Luba could be publicly named. Lady Justice King said that Luba “is clear and has always been clear that she would wish her name to be in the public domain. I have considered whether that is appropriate but in consultation with My Lady and My Lord (i.e. Lady Justice Asplin and Lord Justice Birss, sitting beside her on the bench), we are very clear that we should honour Ms Macpherson’s wishes in that regard.”[4] The intention of the court’s reporting restriction order was to give Luba “the openness she desires, while protecting the Article 8 privacy rights of her daughter” [5].

Lady Justice King then revealed (for the observers this was the first time it was explicitly announced) that the matter “initially listed as an application for appeal against immediate imprisonment” now concerns the issue of “whether [Luba] has capacity to prosecute this appeal”. She asked Oliver Lewis to outline “how we’ve reached this current situation and your proposal of how we proceed today”, and she’d then hear from the parties. Finally, “without sounding like a primary school teacher, can I ask everyone to be very respectful and let everyone have their say and not talk over each other”. This last statement seemed to be aimed at Luba: based on what had happened in previous hearings, the judge may have worried that Luba would interrupt proceedings by speaking when, according to court etiquette, it wasn’t her turn. I looked to see how Luba would respond, and I saw her nod in acceptance.

Oliver Lewis then summarised how things stood – and he was at pains to point out that he was not representing Luba at this hearing, and that documents he’d submitted to the court were not (therefore) “submissions” on behalf of Luba but rather “notes by counsel”. Here’s how it’s recorded in the published judgment: “It should be noted that Mr Lewis, and those instructing him, were at all times diligent in reminding the Court that they did not act upon the Appellant’s instructions and were not making submissions to the Court, but merely assisting by way of providing information and presenting the Court with a number of alternative ways to progress the matter.” (§18, [2024] EWCA Civ 1579,)

Nonetheless, he stated that his instructing solicitor was in WhatsApp contact with Luba, and if she had any concerns, she could contact him. The judge asked Luba to confirm that was okay, and Luba again nodded her head.

In terms of the history of the case, Oliver Lewis outlined the contempt of court case before Poole J which led to Luba being sentenced to 4 months in prison. He said that he had been contacted by Luba in connection with appealing that sentence back in January 2024: she already knew him as he’d acted for her at an earlier stage of the committal proceedings. Oliver Lewis had then got in touch with Mr Michael Barrett, who was to act as Luba’s solicitor for the appeal, but applying for legal aid was a “tortuous process” and it wasn’t approved until 31st May 2024 (the Judge congratulated Mr Barrett on his tenacity). Then the legal team requested a formal transcript of the whole committal hearing but “they” (presumably the transcription service) were under the misapprehension that the request was for the judgment – which in fact had already been published – rather than for the hearing as a whole. Now “the transcription company have said that the audio is too poor to provide a transcript”.

The judge commented that she’d been sent three different versions of the transcript of the judgment itself: the one that’s been published on the National Archives, another where “……only difference is that it includes some conversation that took place during course of judgment where Ms Macpherson became frustrated and the judge turned her mike off”, and then a third, which was the second one with some minor amendments. She thought it “safest … if we all stick to the one in the National Archives”.

I understood from Oliver Lewis’ response that the relevance of the transcript was that in the course of that hearing, Poole J made numerous comments about Luba’s “world view or approach or conduct” – including that she can become “angry and unfocussed” (§6 ([2024] EWCOP 8), that she believes her daughter is being “persecuted” and health care professionals are “part of a conspiracy to torture FP” (§9 ([2024] EWCOP 8); and that the Court of Protection and the Court of Appeal are “corrupt” (§10 [2024] EWCOP 8). Poole’s published judgment also says that “these beliefs are […] deeply entrenched”, and that, despite Luba’s numerous complaints and appeals, there’s no evidence to support these beliefs. Oliver Lewis’ point (I think) is that Poole J’s judgment displays a clear orientation to the possibility that Luba has mental health issues which might influence her capacity with regard to litigation, but despite noting this, Poole J went on to make a judgment sending her to prison without properly considering the implications of the mental health issues he himself had flagged. Unfortunately, since it’s not proved possible to get a transcript of the whole hearing, any such defence would have to rely solely on the published judgments.

Matters came to a head at a meeting (described as a “conference” in the legal documents) in November 2024 between Luba Macpherson, Oliver Lewis (her COP counsel) and Beth Grossman (a media law specialist)[6]: According to Oliver Lewis, “suffice to say that all three of us had concerns about her capacity to instruct Mr Barrett. We are bound by our duty to the court to follow (this) up and to raise any concerns with a client[7] and asked if she’d speak with a psychiatrist and submit to a remote capacity assessment. There should be no shame or stigma in that. We stressed it was neutral and a Litigation Friend being appointed would not mean that she would be silenced in any way: her wishes and feelings would be ascertained and it is a core duty of the litigation friend to tell the court what her wishes are. She refused the remote assessment. I telephoned the Ethics Line of the Bar Council, who said our actions were what would be expected”.

When the Court of Appeal (in the form of Lady Justice King) was informed of the situation, she permitted counsel to instruct a psychiatrist to carry out a paper-based review “not as good as a psychiatrist interviewing her, but we thought that would be better than nothing”. The published judgment sums up this process: “On 6 November 2024, Mr Micheal [sic] Barrett, an experienced Court of Protection solicitor together with counsel Mr Oliver Lewis, a specialist Court of Protection counsel, and Beth Grossman, specialist media counsel, had a remote conference with the Appellant. During the course of the conference each of the three lawyers had concerns about the Appellant’s capacity to conduct the appeal proceedings. As required under their professional obligation, those concerns were raised with the Appellant and she was invited to participate in a capacity assessment which was arranged for 18 November 2024 with Dr Pramod Prabhakaran a psychiatrist experienced in conducting capacity assessments for the Court of Protection. The Appellant declined to co-operate with such an assessment in strong terms.” (§11 [2024] EWCA Civ 1579)

Given that Luba had declined to meet with him, Dr Prabhakaran could only conduct a “paper-based assessment” of Luba’s capacity, based on materials provided to him by the legal team.

Oliver Lewis then went on to describe some of what was contained in Dr Prabhakaran’s report and outlined his conclusions, which are set out in the judgment:

Acknowledging the limitation of a paper-based assessment, Dr Prabhakaran concluded that there was no evidence of a disorder of thought on the Appellant’s part, but there was on the balance of probabilities, evidence of persistent persecutory ideation relating to various professionals and institutions. By reference to the material made available to him, he said: “This suggests that [the Appellant’s] persecutory beliefs persist, even when presented with evidence that could contradict them. Delusions are firmly held beliefs that persist despite evidence disproving or challenging them. For the individual experiencing them, these beliefs feel entirely real and are often resistant to change, regardless of efforts to challenge or disprove them. Based on the information reviewed, it is reasonable to consider, on the balance of probabilities, that [the Appellant’s] beliefs may have reached the threshold of delusional intensity.” (§14 [2024] EWCA Civ 1579)

Dr Prabhakaran concluded, from his paper-based assessment, that “In my opinion, on balance of probabilities, the information available suggests the possibility of a delusional disorder.” (§15 [2024] EWCA Civ 1579))

Having set out the psychiatrist’s conclusions, the hearing then moved on to discussing “Option 3” – although no information had been provided to observers as to what Options 1 or 2 were. The judgment published subsequently does set out the three options before the court: “Options 1 and 2 were that the Court at the listed hearing of the appeal on 3 December 2024 either (Option 1); declared that the Appellant had litigation capacity or (Option 2); declared that she lacked litigation capacity. Both of these options were quickly dismissed, there being no sufficient evidential basis upon which this Court could have concluded either way. The focus of the hearing was therefore on Mr Lewis’ “Option 3” an option favoured also by the Local Authority”. (§19 and §20 [2024] EWCA Civ 1579))

Option 3 turned out to be sending the case back to the Court of Protection, to determine whether Luba had capacity at the time of the January 2024 committal hearing (something Lady Justice King said “goes to the heart of the appeal”), and whether or not Luba has capacity now to appeal Poole J’s committal judgment. The Court confirmed that it had all the powers of a lower court in relation to an appeal and therefore was able to make an interim declaration that the Appellant lacked litigation capacity. The Court invited the Official Solicitor to act as interim litigation friend. Oliver Lewis suggested that “(as) she’s lost faith in Mr Justice Poole and the Court of Protection, it may be appropriate to transfer (the case) to the Vice-President” ( i.e. Mrs Justice Theis). Lady Justice King acceded to this request: “While not accepting any criticism of Mr Justice Poole, we perfectly understand she would struggle to cooperate with any capacity assessment unless the matter was being considered by fresh eyes”.

In summary, Option 3 was that the court could make an interim declaration that Luba lacked capacity to conduct the current proceedings. She would become a protected party in the Court of Protection, and the Official Solicitor would be appointed as her Litigation Friend. That means she couldn’t choose her legal team directly, or represent herself as a Litigant in Person. This was explained in the judgment: “Option 3 was that that Court could make an interim declaration pursuant to Section 48 of the Mental Capacity Act 2005 (“MCA 2005”) on the basis that the Court had “reasons to believe that the Appellant lacks capacity”. Option 3 envisioned the Court of Appeal then transferring the case to a Tier 3 (High Court) Judge of the Court of Protection in order to determine the matter of capacity before the matter was returned to the Court of Appeal to hear the substantive appeal on a “firmer capacity footing”” (§ 20 [2024] EWCA Civ 1579).

Counsel for the Local Authority also agreed with Option 3.

I could see Luba was listening intently to the proceedings. The judge then invited her to speak. Here, as best as I could capture it (with Celia Kitzinger’s input too), is what happened next:

Judge: Ms Macpherson, as you will be aware, we are not dealing with your appeal. We know you are appealing the sentence of immediate imprisonment. But we can’t get on to the appeal until we have dealt with the issue raised by Mr Barrett as to your capacity. I know you don’t agree. Mr Barratt and the legal team have no alternative, once they’ve formed the view (wrongly in your view) that there’s an issue with your capacity, but to take the steps they’ve taken. We know you don’t agree, but procedurally that’s absolutely where we are. What we have to decide is what we do about that information, because the issue of capacity has now been raised.

Luba: The issue about my capacity comes from faulty notes because they write in their notes out of context and I inform them, and still they insisted. Let me say my say, and then I let you decide which way you go. I will not in any way undergo capacity assessment. After six years in the COP, I witness misinterpretation of capacity assessment. My daughter’s experience is against Mental Capacity Act. The psychiatrist made the decision my daughter lacks capacity six months before he met her. I can prove that COP has no jurisdiction and that MCA was misused. So, no way I will go through capacity assessment. How I fight my case? Please consider the issue now is the European Court of Human Rights. It’s a very dangerous game just because of inaccurate notes and lies by my supposed-to-be representatives. I will read my speech because I have prepared it.

Judge: I think what you are saying in summary is that you don’t trust any psychiatrist because in your view an independent psychiatrist has wrongly assessed that your daughter lacks capacity. I want to understand your case and your submissions.

Luba: What I want to say is in Britain today Court of Protection lawyers are abusing the law and the people who are already vulnerable are being mistreated. Courts are being misused so that authorities can act. The MCA is supposed to empower, but authorities can act without accountability. My family is harassed and tormented because LA would not provide services and fabricated a story that my daughter needed protection from me. They fabricated stories, abused her with treatment. And Oliver Lewis said there was supposed to be trauma informed treatment – what’s happened to that? And Oliver Lewis – what happened to his ‘trauma-informed’ treatment’?” [Note: This has been corrected as requested by Luba , who says: ” What I said was in direct reference to Oliver Lewis’s own Skeleton Argument from several years ago, which he authored during the earlier committal proceedings. In that document, he spoke at length about the importance of trauma-informed treatment, how I had been “set up to fail,” and how there had been procedural errors and breaches of Articles 6 and 8 of the ECHR. So at the appeal hearing, I was not quoting him vaguely, I was asking a pointed question:“What happened to his ‘trauma-informed’ treatment?” Because the trauma hasn’t ended, it has worsened, and tragically, Oliver Lewis later became part of the machinery that inflicted it.He went different route based on lies.”]

Judge: Pause!

Luba: Let me get it out of the way. I’m very upset by the treatment of my own lawyers. They misuse the MCA by claiming my inability to instruct them. This is only faulty notes – and they shamelessly lied. I can prove that. The question of my capacity is only because I disagree with them. But is anyone questioning their capacity because they disagree with me?

Judge: I’m sorry, Ms Macpherson-

Luba: I have to say! I’ve been waiting for transcripts as promised and eventually I am told the audio is of very poor quality, this is more lies. This is intolerable and beyond the limits of endurance. Now my barrister wants it all delayed again. There must be no further delays. It must be heard today. Oliver Lewis says that’s the way the system works and I have to accept it: I have a recording. It’s been seven precious years of time with my daughter. I lost seven precious years with my daughter. (Note: This has been corrected, as requested by Luba who says: “Misquoted: “Seven precious years of time with my daughter” This was almost certainly a mishearing, perhaps due to my accent. What I actually said was: “I lost seven precious years with my daughter.” There was no “time with” her, that is the point. These were lost years, taken by a system that I was desperately trying to challenge.) No Christmas together. No birthday parties. I lost time with my daughter. My daughter lost time with me.

Judge: Please stop, or I will turn off the microphone.

Luba: No, no, no no. No, listen to me.

(Judge turns off mike)

Judge: I understand your deep frustration at the poor quality of the recording. I can only apologise on behalf of the system. While there has been a delay, you want to appeal against the sentence imposed on you by the judge. You accepted that you had breached the injunctions and your appeals were dismissed without merit. You are coming to this court, as you’re entitled to do, if you have capacity, to appeal against your sentence. I know that you are living in France. As far as your daughter is concerned, your right of appeal is exhausted or not taken up. She is living in a placement which is approved by the court. This court is not now concerned with those issues.

Luba: (I can see Luba is talking but I can’t hear her as the judge has muted her.)

Judge: We want to hear what you have to say about assessment of your capacity. You say your lawyers have shamelessly lied and made false notes and only raised concerns about your capacity because you disagreed with them. I understand your frustration at the various delays. I understand you’ve declined to come back to this country. Now I will turn on the mike again and ask if there’s anything else you want to tell us about whether your appeal should now go to a different High Court judge as to your capacity to pursue this appeal. If the judge decides you have capacity you would come back here. If the judge decided you did not, then the committal order would be discharged because it should not have been made.

The judge unmutes Luba.

Luba: In no way will I go under capacity assessment in England. European lawyers have no doubt about my capacity. I can do it in France. After six years of legal abuse, I don’t trust the system in England. My lawyers have told me I have to accept the system, but claims about my capacity are part of a pattern that I have a weakness. They use same speech. I hope you see what is going on with the system. This is another extension of mental health abuse. They are covering up the faults of Local Authority and Court of Protection and against everything Article 6 of the Human Rights Act lays down. This is a cover up and defamation of my character. I have no mental illnesses or cognitive impairments. No assessment of my mental capacity can be made that takes hearsay evidence from others. No assessment can be made except at the moment of decision. I ask my solicitor to study the Mental Capacity Act. There have been multiple mistakes in law. I have explained to my solicitor the steps that must be taken.

Judge: You are drifting away from the subject.

Luba: No, I’m saying what my lawyers said to me. But it must be my defence that I publish videos to show the injuries caused in care-

Judge: You are drifting away from-

Luba: No, no, no, I am trying to explain. It must be my defence that I publish photos and videos-

Judge: I am going to turn off your mike because we’re no longer dealing with the issues that are before us.

The judgment records what happened in the following way: “The Appellant [Luba] expressed her views about Option 3 [a CoP determination of her capacity to litigate] clearly and strongly over a remote link. She became at times agitated and unsurprisingly, had difficulty in limiting her submissions to the issue of the necessity (or otherwise) for there to be a capacity assessment and determination. The Court was obliged to turn off the Appellant’s microphone on a number of occasions during the hearing when she was unable to restrain herself or to listen to what was being said by others.” (§21, [2024] EWCA Civ 1579).

The order the judge made was adoption of “Option 3” which the judge read out in full. Rather than declare either that Ms Macpherson has litigation capacity (Option 1), or that she lacks litigation capacity (Option 2), the court declared that having considered the available evidence, there was “reason to believe” (the wording of s.48 MCA 2005) on the basis of the psychiatric evidence that Luba lacks capacity in relation to conducting the appeal – although they “had in mind the limitations of the paper psychiatric assessment.” (§25). The court made an interim declaration that she lacks capacity, and invited the Official Solicitor to act as litigation friend on an interim basis. The judges referred the case back to the Court of Protection, for a High Court judge to determine the matter of capacity, before the return of proceedings to the Court of Appeal to hear the substantive appeal (against committal).

Because of the interim capacity ruling, the finding from that January 2024 hearing was put on hold and the arrest warrant paused too. Luba could not be arrested and imprisoned until the capacity issue had been decided. But the injunctions prohibiting Luba from publishing information about her daughter remained in place.

Luba made it clear that she was unhappy with this outcome.

Luba: Why you are not listening that doubt about my capacity comes from lies about conference notes?

Judge: I was listening, and if you remember I read back to you your submission about that.

Luba: Are you joking, people? You are judges and lawyers and you are abusing the law.

I am not participating in that. I am going to European court. I explained to my solicitor on daily and weekly basis that appeal must be against perjuries of social workers, lack of capacity, criminal actions of barristers in withholding (missing word?). The judge acted beyond his powers by instructing police to walk away from criminal activities. I found an expert who is willing to examine my daughter’s prescriptions and the interactions of her drugs.

Judge: Ms Macpherson, Ms Macpherson, Ms Macpherson! Enough! If you cooperate you will have an opportunity to tell the expert who’s instructed. You will have an opportunity to say all of that. You will be able to explain it to the expert.

Luba: The administration of justice- This is a- I was not even allowed to say my say at this hearing.

Judge: I’m going to turn off your mike and make the orders.

The Court of Appeal hearing ended shortly afterwards.

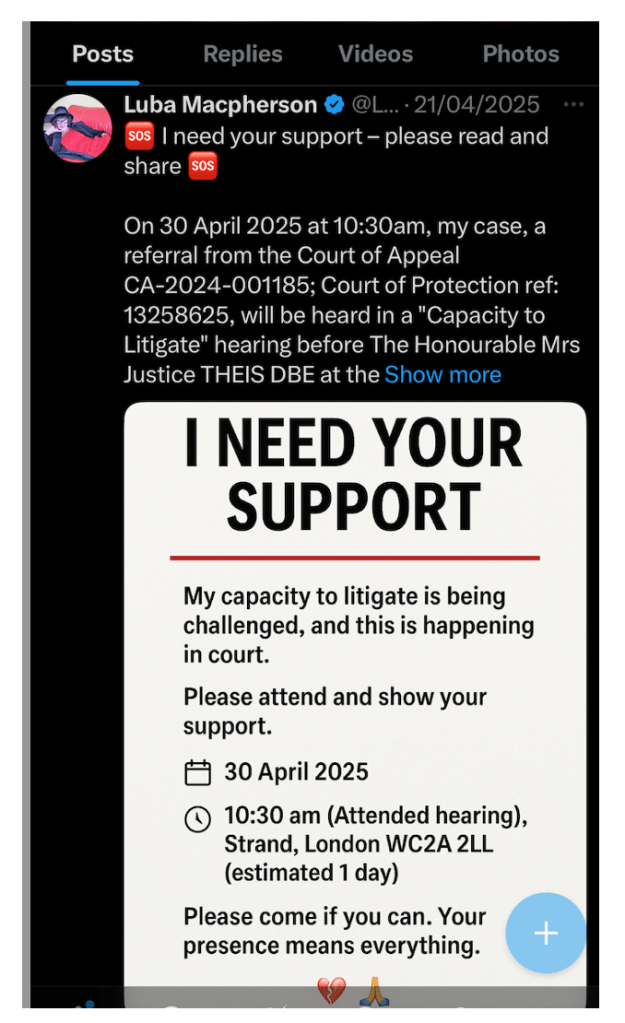

The next hearing (intended to determine Luba’s litigation capacity) was listed before Mrs Justice Theis, the Vice-President of the Court of Protection, on 18 February 2025. Luba promoted the hearing heavily on social media and asked people to watch it.

2. The Court of Protection hearing 18th February 2025: Courts seeks to determine Luba’s capacity to litigate proceedings, but independent expert did not appear

It’s unfortunate that there were transparency issues with this (fully remote) hearing, before Mrs Justice Theis. Although there were quite a few people on the link when I joined, I know of at least one person who tried to observe and couldn’t, and from looking at Luba’s social media accounts afterwards, I discovered she wasn’t the only one. I think the court staff found it difficult to manage the demand for links.

In this hearing, Oliver Lewis was representing Luba but taking instructions from the Official Solicitor rather than from Luba directly (since the Court of Appeal had made an interim declaration that Luba lacks litigation capacity).

The original plan was for evidence to be presented at the hearing in order for the judge to come to a decision about Luba’s capacity to litigate – but in the event, this turned out to be a very short hearing, only about 30 minutes, as there was a problem. The court could not get hold of the expert witness, Dr Prabhakaran, the psychiatrist who had conducted the paper-based assessment of Luba’s capacity. He had not responded to requests for further information. Indeed, even on the morning of this hearing, a call to his secretary proved fruitless. It seemed that he was “ghosting” the court.

Without his evidence, the court did not have sufficient evidence to make a decision as to Luba’s capacity. Oliver Lewis, proposed that, if subsequent efforts to contact Dr Prabhakaran failed, a second psychiatrist should be appointed by the court and “instructed to conduct a desktop review”. He said: “I am also filing a correspondence bundle which (consists of) several hundred pages ….We will be going back to an independent expert to be instructed within seven days and give them 6 weeks to report”. I gathered that the correspondence bundle was correspondence between Luba and her legal team. The new expert would consider both that bundle of documents and the bundle for this hearing, and a new hearing to consider all the evidence would be held in late April 2025.

Counsel for the LA, Sam Karim KC, stated that it was a “shame that Dr Prabhakaran is not in contact…if he is not willing or able….. (to) provide further evidence, he should be asked to explain”. Theis J agreed with the proposal for the appointment of a second expert, although she also wanted to know more about exactly what efforts had been made to contact Dr Prabhakaran. She also stated “I hope Ms Macpherson will cooperate with the assessment …then the assessment has the benefit of her engaging directly”.

There was also the issue of who represented Luba. Oliver Lewis explained that Luba had applied to remove the Official Solicitor (currently she was instructing him) as her litigation friend but argued that “the application is premature as these proceedings before you are to determine capacity, so we see that as a matter for the Court of Appeal, and Ms Macpherson proposes no alternative litigation friend”. There was then some discussion about the legal rules over who should hear this appeal from Luba to remove her litigation friend, as it was the Court of Appeal that had appointed the Official Solicitor as Luba’s litigation friend, and not the Court of Protection. In the end, the judge stated that “it’s not a formal application, ……it is a two-page document, it sets out wishes but no alternative is proposed. So, I’m not going to make any determination today in that matter, but Ms Macpherson will hear what I am saying, and she can refer the matter to the Court of Appeal if she wishes”.

Finally, Oliver Lewis stated that there had “been all sorts of satellite applications (which he set out)… part of a pattern of satellite, if I could put it that way, litigation ..that Ms Macpherson wants to re-open the substantive proceedings and wants the court to get to grips with injustice as she sees it. But I have explained to Ms Macpherson that these proceedings are to deal with capacity”. He wanted to make clear that the original substantive proceedings to do with Luba’s daughter have finished. Matters now concern only contempt sentencing, and Luba’s capacity to litigate those proceedings.

Mrs Justice Theis listed the next hearing as in-person, in a couple of months time, at the end of April. She explained that Luba would be able to attend the hearing in person, as there was no longer an active warrant for her arrest. If she wanted to attend remotely, she should “make that application with reasons”. She added that she would prefer the expert to attend in person too, but similarly they could apply for remote attendance.

And that was the end of the hearing. Unlike previous hearings I’ve observed, the judge did not invite Luba to speak.

In short, because the psychiatrist, Dr Prabhakaran, who had written the report on Luba’s capacity to litigate proceedings, was not available to give evidence, the hearing could not proceed. Either he would give evidence at a future hearing, or the court would appoint a new expert to assess Luba’s capacity.

3. The Court of Protection hearing 30th April 2025: Evidence from the expert as to Luba’s capacity to conduct proceedings

As Mrs Justice Theis had directed, this was listed as an in-person hearing. Unusually, this time the court was robed (i.e. the lawyers were wearing wigs and gowns).

Luba had again promoted her hearing heavily on social media, asking people to come along.

In the event, the court provided a link for observers (as it often does for in-person hearings) and I was able to observe it remotely, along with four others whose names I recognised from my involvement with the Open Justice Court of Protection Project. There were also a couple of people I could see at the back of the courtroom, in the area where members of the public usually sit, so I think there were also other observers I didn’t know.

The seating arrangement in court was quite striking. On the right-hand side (from the judge’s perspective) of the front bench, where counsel usually sit, I saw Luba, dressed very smartly in black, with a big black bow in her hair. She was sitting next to a man who did not appear to be a lawyer, and in front of Sam Karim KC (counsel for the Local Authority). Oliver Lewis was further away from her, to the left. Luba is very familiar by now with court protocol and I am pretty sure she knowingly selected for herself the position usually taken by the applicant counsel.

The hearing started with Oliver Lewis (counsel for Luba again, but as at the last hearing instructed by the Official Solicitor) explaining to the judge who the man sitting next to Luba was. He turned out to be Barry Gale of Mental Health Rights Scotland. He said that Luba wanted Barry Gale to act as her McKenzie friend. A McKenzie Friend is someone who isn’t a lawyer but who provides support to a person involved in a legal hearing: their role is to assist a litigant in person (i.e. someone who doesn’t have legal representation) during court proceedings. Oliver Lewis pointed out that Luba was not a litigant in person: he was representing her. He proposed that Barry Gale “can sit next to her and support her, take notes, and quietly offer support and suggestions (like a ‘normal’ friend)”, but that he could not formally act as a McKenzie friend. The judge asked Luba if she was content with that and Luba replied “Yes, what else can I do?”. So, Luba was supported by her ‘non-McKenzie friend’. In practical terms, this made very little difference – but symbolically it did rather draw attention to the precariousness of a protected party’s position when “their” lawyer (appointed via a litigation friend) takes a position contrary to their own. In this hearing, Oliver Lewis (acting for Luba) submitted that Luba lacked capacity to conduct proceedings. By contrast – and in line with Luba’s own position – counsel for the local authority (Sam Karim KC) submitted that she did have capacity. (At one point in the proceedings, as a break had been called, I saw Luba turn towards Sam Karim KC and thank him.)

Dr Prabhakaran, who’d been missing from the previous hearing, was back and now appeared in person in the courtroom. There was no explanation as to his non-appearance for the February hearing. The hearing focussed on Dr Prabhakaran’s assessment of Luba’s capacity to conduct proceedings so that the judge could decide:

- Does Luba have capacity to conduct an appeal against the prison sentence she received from Poole J on 22nd January 2024?

- Did Luba have capacity to conduct contempt proceedings on that date?

Dr Prabhakaran’s capacity assessment was still ‘on the papers’, i.e. based on a desk-top analysis of her correspondence and social media posts, rather than on a clinical interview with her. There was a last-ditch attempt to remedy this, but it failed. Oliver Lewis explained to the judge that, as both Dr Prabhakaran and Luba were now at the court in person, he’d asked Luba if she wanted to meet with Dr Prabhakaran, so that he could interview her in person, but Luba, he said, had declined the invitation. She did so again in court. She said “He can observe me in this court hearing. I give you this opportunity to test me….I’m here to prove that I’ve got capacity. Let’s do it!”

The judge said it was “a matter for her”, but again suggested that Luba might want to meet Dr Prabhakaran before he gave his evidence. Luba said that she could meet him afterwards, so that “he gives his evidence and then I give mine”. The judge stated that was the wrong way round but Luba stood firm. She pointed out that he’d “had his opportunity on 18th February, but he didn’t attend”, adding “I don’t like to be accused of delusions….it’s a joke”.

The plan for the morning was then set out: the expert witness, Dr Prabhakaran, would be questioned first by Oliver Lewis (whose witness he was), then by Sam Karim KC and then by Luba herself, with a 30-minute time limit for each of them suggested by the judge. This surprised me. Luba, now in the role of a protected party, was going to be allowed to question an expert witness, even though she had her own legal representation!

But first, before the questioning of Dr Prabhakaran started, Oliver Lewis told the court that there had been a problem when Luba had arrived in the UK a couple of days before the hearing. She was “very unfortunately arrested” and “spent the night in custody” after she got off the ferry from France. Apparently, the Court of Appeal order staying the warrant for her arrest had “not made its way on to the police computer”. This was pretty shocking!

It was also clear that Luba had written an opening speech she wanted to read to the court but the judge said “the better course is to get on with the doctor’s evidence. Once we’ve heard that, everyone will have the opportunity to say what they want to say about capacity”. Luba did not challenge that.

Oliver Lewis opened the questioning by asking Dr Prabhakaran about his experience with capacity reports in the COP and established that he’s produced about 140 reports on capacity, a “large proportion” of which deal with capacity to conduct proceedings. Counsel explored the limitations of a capacity report based only on documents and without medical evidence, and the doctor accepted that this had hampered him but that the documents nonetheless provide “a rich picture” that offers “a lot of information about Ms Macpherson’s ways of thinking”.

Counsel asked Dr Prabhakaran whether Luba’s background, in particular the fact that she grew up in the USSR and post-Soviet Russia, could influence her judgment of institutions, even though she has lived in the United Kingdom for 30 years. Dr Prabhakaran replied that he had practiced for 25 years in London and that the Russian people he knew “have managed to put aside suspicions” and he found there was much more trust by them in the UK legal system.

Dr Prabhakaran went on to say that he had formed his opinion, on considering all the documentation, that Luba has a “complex belief system (that) included individuals, the court system, professionals….(in her) desire to pursue justice for her daughter”; the belief system was “fixed and pervasive”; she has a “suspicion and belief that the system is conspiring against (her)….the local authority being responsible for care was the initial focus of persecution beliefs …which now expanded to the legal system”. He reported that Luba had “written letters to the Prime Minister, the leader of the opposition, and others… highlighting a complex conspiracy by lawyers and other professionals”.

He did accept that he had not been able to test his “logical conclusion” that Luba lacks capacity to conduct proceedings, by meeting her. After the judge asked him whether he would like to be able to have the opportunity to do that he replied “ideally, yes”. He stated that the disturbance or impairment to the mind or brain was “a complex delusionary personal belief system”, which could be limited to this very small issue of capacity to conduct proceedings in this case, and which may not affect other areas of her life. So, she could have capacity to conduct proceedings concerning a dispute with a neighbour about a fence boundary, for example, while not having capacity to litigate in any matters regarding her daughter’s case. Oliver Lewis asked if the delusional beliefs had got worse over time and Dr Prabhakaran thought that they had.

I noticed that Luba was sitting and listening very carefully to all that was being said. She did not try to interrupt once.

Then it was the turn of counsel for the LA, Sam Karim KC, to question Dr Prabhakaran. His questions focussed on how many purely paper-based assessments he had done previously (very few, usually it was paper and interview). Dr Prabhakaran confirmed that he had spent days reading the information, including some social media posts, but he had not had access to Luba’s medical records, which would usually be the case for a capacity assessment. He stated (again) that there would be benefits to having a conversation with Luba, and that confidentially one-to-one would be better than through an exchange in court as part of giving evidence. He said that the core issue was her system of beliefs that has led to a mistrust of the entire system. Her inability to use and weigh relevant information was secondary to her belief system and that this meant she was not making “unwise” capacitous decisions, but rather displaying evidence of a lack of capacity. He added that her delusions were not “bizarre” ones such as imagining that she could fly like Superman, or hear messages through the radio, and that her delusions were “understandable in the context”. But he found them to be delusions nonetheless.

Both counsel and the judge drew attention to the fact that at various points in the proceedings, Luba had been represented by solicitors and barristers (including Oliver Lewis) who considered that she did have capacity to litigate – or at least took instruction from her without demur, and did not raise any concerns about their client’s litigation capacity with the judge (then, Poole J).

Then it was Luba’s turn. She thanked the judge for being given the opportunity to speak, and the judge reminded her that she must ask questions and not make statements. As Luba was speaking, the judge helped her to turn some of her statements into questions. Luba had obviously prepared carefully.

She began by asking Dr Prabhakaran what he considered to be delusional beliefs. “They are fixed beliefs that are against the factual evidence” he replied. “Okay,” said Luba, “you think that delusions are beliefs in things that did not happen, but I have so much evidence that these things did happen…. Where is the evidence that my beliefs are delusions if I have material evidence that exactly shows abuse?”

The judge intervened to rephrase the question to Dr Prabhakaran as: “So, can it be said that Ms Macpherson’s beliefs are delusional if she has material evidence that her daughter hasn’t been protected?” Dr Prabhakaran replied that the evidence Luba was referring to applied to “just one group of carers” and that she was accusing “the system” of abuse – which, he said, “is much wider than where there could be a genuine grievance”. Later he added, “There is an element around your daughter’s case that concerns health care professionals, but it’s expanded to cover (I think I heard him laugh here) most organisations”.

“The attempted abduction you describe as delusion – why?” asked Luba. This relates to an incident previously reported by Luba when she says there was an attempt to abduct her and place her in a mental hospital. “I didn’t consider it in isolation”, said the Doctor. Luba persisted: “What evidence do you have there wasn’t an abduction?” and he replied “I don’t have evidence one way or the other”. She also replayed to him his statement that “Ms Macpherson may meet the threshold for delusional intensity” asking “Do you agree that ‘may’ implies uncertainty?”

At one point Luba did stray on to the (for her) important issue of her daughter’s diagnosis and treatment but the judge reminded her that “we are not dealing with treatment for now”. So, Luba returned to the issue of “presumption of capacity” embedded in the MCA 2005: “Did you consider my decisions, while unwise in your view, might still be capacitous?”

When Luba finished her questioning, the discussion in court started to revolve around why Luba’s legal team in earlier proceedings had not raised the issue of her capacity to conduct legal proceedings, and then returned to whether Luba would consent to being interviewed by Dr Prabhakaran. She still declined the offer.

One final issue was whether Luba could ask questions of her legal team. She believed that they had lied, and that their notes from the November 2024 meeting, when the question of capacity had first come up, were faulty. However, Mrs Justice Theis pointed out that the Court of Appeal (§24 of the judgment) had already considered this issue and stated that the court “can see no basis for the allegations against the legal team” who had “acted wholly in accordance with their respective codes of practice” and that there was no reason to believe they had acted inappropriately. As a result, Theis J did not allow Luba to question them.

Mrs Justice Theis then asked for written submissions “limited to 10 pages” from both counsel, and from Luba herself. She said there would be an in-person hearing at which she’d hand down judgment on 15th May 2025, and she asked Luba to attend in person. Her final point was to reiterate that the relevant border authorities need clarity, so that Luba is “free to go in and out of the country”.

Several aspects struck me as unusual at this hearing. This was a hearing with a protected party, P, present in court, represented by her litigation friend, the Official Solicitor. But this protected party, Luba Macpherson, chose to sit in proximity to the legal team for the local authority and indeed thanked the local authority’s counsel for his questioning of the expert witness. Luba was also allowed to have a “(non-McKenzie) friend” helping her in court, even though she was represented in the hearing by a legal team. Finally, and virtually unknown in my experience for any other “protected party” in the Court of Protection, Luba Macpherson herself was allowed to spend 30 minutes questioning the expert and to make written submissions after the hearing. Given the skills Luba displayed during the course of the hearing, and the way in which the court had allowed her to participate, I remember thinking that it would have been remarkable if Theis J had decided that she did not have capacity to conduct proceedings.

4. Handing down of the judgment 22nd May 2025: Luba has capacity to litigate

The judgment was delayed until 22 May 2025. Luba kept her followers updated on X – but there was another problem with transparency. When the listing for the handing down of the judgment was published the evening before, it stated that the hearing was “Applications in Court as in Chambers”, which means it wasn’t open to the public, so I assumed that I would not be able to observe. However, just before the hearing was due to start at 10.30, the listing was updated to say “in open court”. Unfortunately, I didn’t become aware of that until 10.45. I sent a request for a link immediately, but I wasn’t admitted until 11.16. I could see that Luba was attending remotely. Otherwise, I was the only other person on the link – not surprisingly. When hearings are supposed to be open to the public they really do need to be properly listed as such in good time – and this is especially important when a protected party or their family (like Luba in this case) really want observers to be present. It felt quite undermining of Luba that this wasn’t properly listed.

When I joined, I could see Oliver Lewis and Sam Karim KC in court but I realised that the judgment had already been handed down, and I’d missed it. Theis J was addressing Luba. The first words I heard Theis J say were “national archives” which led me to believe that she was allowing publication of the judgment. I heard Luba ask her if this would be a “new precedent”. The judge didn’t answer this question but said that she would issue her order, and the case would go back to the Court of Appeal, and they would list a new appeal. She then said to Luba “It is up to you to retain legal representation; that’s up to you”. That’s when I realised that the judge had found Luba to have capacity to conduct proceedings. The published judgment is here: [2025] EWCOP 18 (T3)

Oliver Lewis asked about arrangements for discharging the Official Solicitor as litigation friend and Theis J replied that as it was the Court of Appeal that had invited the OS to represent Luba, it would be the Court of Appeal who would deal with that. Oliver Lewis also referred to the “discharged bench warrant” and Mrs Justice Theis stated that it “might be sensible to record that Ms Macpherson said she is back in the country”. Luba had confirmed that she was planning to stay in the UK. Now that she has been found to have capacity, she could be arrested again. I don’t know if the bench warrant will only be reinstated after the Court of Appeal hearing. The legal aid certificate would remain, and the judge stated that the court would “ease passage back to the Court of Appeal” and it should be listed for “sooner rather than later”.

And with that the hearing ended. I looked at Luba on the link. She was smiling broadly.

The judgment was published the following day [2025] EWCOP 18 (T3). Mrs Justice Theis found that Ms Macpherson has capacity to conduct her appeal against Poole J’s prison sentence, and that she’d had capacity to conduct the earlier contempt proceedings that led to that prison sentence. Her reasons (set out in §56) were:

(1) The presumption of capacity is “a fundamental safeguard of human autonomy” which “requires cogent, clear and carefully analysed information before it can be rebutted”.

(2) The court needs to guard against finding a lack of capacity based simply on reference to an aspect of a person’s behaviour (s2(3) MCA), like Ms Macpherson’s entrenched and strongly held views

(3) Whilst her capacity to conduct this appeal is decision and time specific, the “wider evidential context” cannot be ignored: for example, she was able to conduct the appeal in May 2023 as a litigant in person that involved similar issues, namely committal, and the Court of Appeal did not raise issues regarding her capacity to conduct that appeal, even though she was unrepresented.

(4) There is only limited weight the court can attach to Dr Prabhakaran’s paper-based assessment. He had not seen the medical records, did not interview anyone else who knew Ms Macpherson and was unable to assess Ms Macpherson in person. “Despite his experience and expertise set out in his report, Dr Prabhakaran’s written and oral evidence was hesitant, somewhat superficial and lacked any considered analysis or underlying rationale.” Also, his reports and oral evidence lacked any real consideration of the presumption of capacity, what steps could be taken to support capacity and consideration of unwise decisions. He failed to consider adequately, or at all, the history where Ms Macpherson had been able to conduct similar proceedings, despite her fixed and firmly held beliefs.

(5) “During the proceedings before this court Ms Macpherson has largely complied with directions made following the referral from the Court of Appeal and participated in the hearing on 30 April 2025, with the support of the person present with her in court and accepted the decision I made to manage the issues she could raise and the questions she asked”.

(6) “It is not unusual behaviour for litigants who hold strongly held beliefs to make multiple applications to the court. “It does not equate with lack of capacity on its own and can be managed by the court through the exercise of appropriate case management powers.”

Reflections

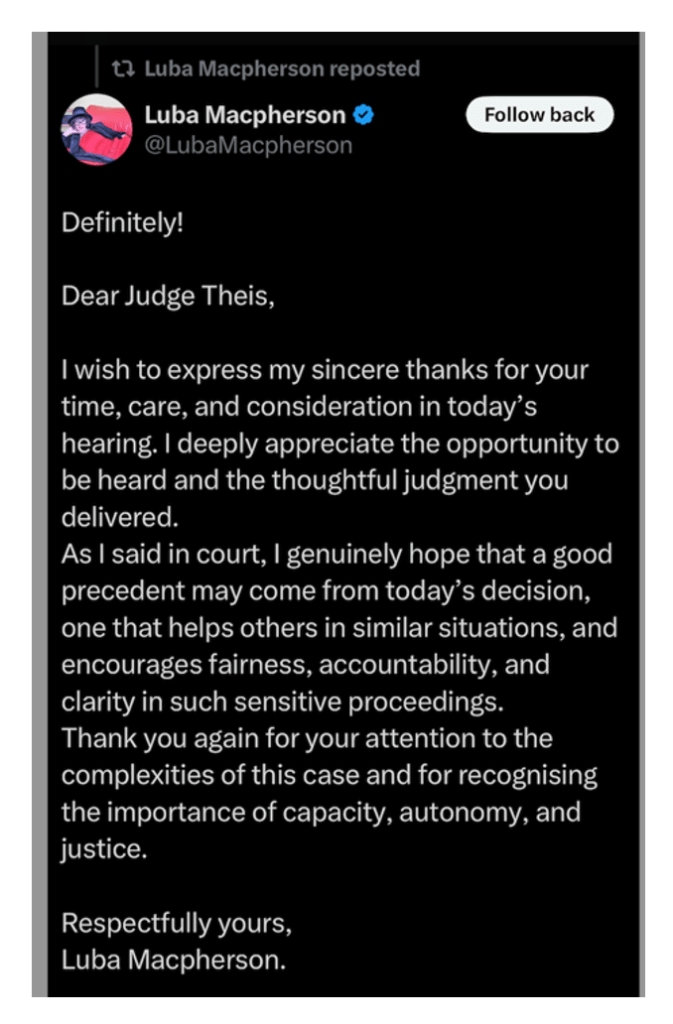

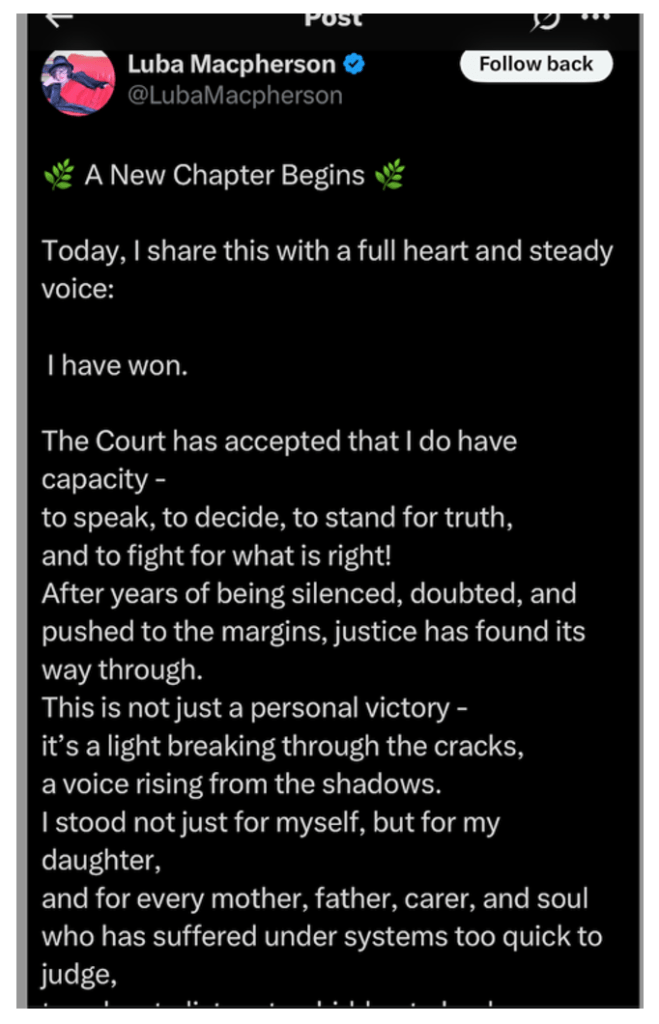

Luba’s postings on X after the judgment are jubilant. She thanked the judge.

She published a poem translated from the Russian about “a sudden truth” and wrote of herself (in the third person) as someone not delusional, not broken – as someone fighting for justice and truth[8].

The finding that she has litigation capacity seems to have spurred Luba on in her campaign. This is Luba’s pinned X post (with the pixelated photo of her daughter redacted):

Luba’s posts have inspired a dedicated following on X and Facebook, creating a space where others who feel misunderstood or abused by the courts (both the Family Court and the Court of Protection) can also speak out (often, necessarily, anonymously), with hashtags like #MiscarriageofJustice #ExpertWitnessReform and #LegalAbuse. She connects her own experience with other newsworthy failings in the justice system, including the Post Office scandal. I am interested in learning more from Luba about how she has developed her social media campaign, the changes she wants to create, and how successful she thinks her campaign is.

Judgments are rarely published from the Court of Protection but this blog includes excerpts from two: one from the Court of Appeal hearing and the other from the Court of Protection hearing that followed it. It is very useful to have the judgments to understand why a judge (or judges) have made the decisions they have, and to understand how judgments are understood and received by parties to the case, and by the public.

In reading judgments from hearings I’ve observed, and formed certain opinions about, it’s interesting to reflect on the choice of words: like “bizarre” (§13 of the CoA judgment) which refers to “emails from the Appellant written by her in somewhat bizarre terms, as recently as 22 November 2024”. Poole J’s judgments also use the word “bizarre”. The choice of the word “bizarre” seems to me to be leading the reader to an assumption about Luba. And §21 of the same judgment states: “The Court was obliged to turn off the Appellant’s microphone on a number of occasions during the hearing when she was unable to restrain herselfor to listen to what was being said by others.” There is a certain etiquette that the court is used to and expects others to follow. But lay people are not familiar with it. Luba had prepared a speech that she wasn’t allowed to deliver and was trying to get her voice heard. I imagine it was very frustrating for her. The judgment presents one narrative; I formed a different point of view from observing the hearing.

Judgments are very powerful tools of justice, analysed by legal experts and used by lay people such as me. I believe that, much like media reporting, how litigants are represented, or framed, in judgments is to a certain extent an editorial choice. The use of certain words, and how exchanges within a hearing are reported, matters. It is an area I plan to explore more in my PhD research.

The 30th April 2025 hearing lasted for five hours, including breaks. Luba listened intently to the questioning of Dr Prabhakaran and put together questions of her own. Her questions were of course not as rigorous or well-constructed as those of the qualified and experienced barristers, but I admire her ability to speak in court, especially as English is not her first language. As somebody who lives in a country where English is not the main language, I know how difficult speaking in a second language is. I wouldn’t be able to do what she did. I also reflect on how having an accent can impact how people see you and what they think of you, as I’ve had experience of that too.

As the day of the judgment approached, I found myself thinking about it more and more. How, if Luba was found not to have capacity to conduct proceedings, that would set the bar for capacity so very high. No capacity, for a very limited context, based on a paper exercise, including a review of emails and social media posts. Because of her beliefs. Beliefs that are shared by many people – including, as Bruce Springsteen said, albeit in a very different context, in the quote with which I opened this blog, that she is being persecuted for using her right to free speech and voicing her dissent.

Luba believes “the system” (a term that came up repeatedly across the hearings) is against her and she has lost trust in it to protect her or her daughter. From what I know, she isn’t alone – and there have been aspects of how this case has unfolded that can only have increased her mistrust. One example is her arrest after her return to the UK to attend the 30th April hearing, because Border Control were not aware that the arrest warrant had been ‘stayed’. When the judge commented that the ‘stay’ had “not made its way into the system”, I thought to myself well, that won’t help Luba’s trust in ‘the system’.

I believe that Paragraph 56 (2) is a very important part of the judgment: “The court needs to guard against finding a lack of capacity based on reference to a person’s condition or an aspect of their behaviour which might lead others to make unjustified assumptions (s.2(3) MCA). An aspect of Ms Macpherson’s behaviour are her entrenched and strongly held views, yet it has been shown over an extended period of time when those views have not significantly changed, she has been able to effectively conduct and be involved in litigation concerning directly or indirectly the Court of Protection proceedings regarding her daughter, both with and without legal representation.” [2025] EWCOP 18 (T3).

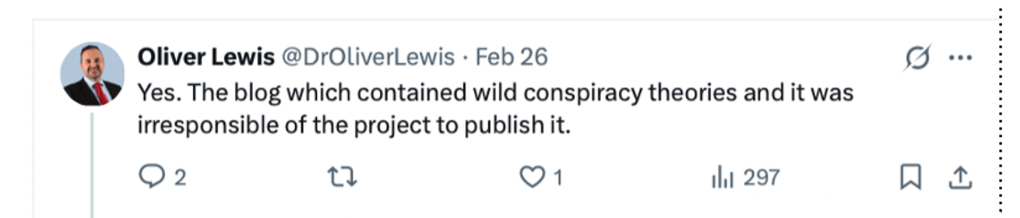

Shortly before the judgment appeared, I’d attended a webinar for the book launch of Dr Charlotte Proudman’s new book, He Said She Said, on 28 April 2025, with Louise Tickle and Kate Kniveton in discussion with Dr Proudman. Looking through the list of participants during the webinar, I’d say that over 90% (and possibly more) were women. There were many comments in the chat that the Family Court is corrupt, and a lack of trust in the legal system came through very clearly. So-called conspiracy theories are rife on social media – indeed, Oliver Lewis used X to claim that one of the Open Justice Court of Protection blog posts (reporting on a different case in which he also acted as counsel) contained “wild conspiracy theories”[9].

I can’t imagine anything worse than having your capacity questioned when you are fighting against something you believe to be a grave injustice, especially concerning a family member. In my opinion, if Luba had been found to lack capacity to conduct proceedings because of her “entrenched beliefs” that would have opened the door for a lot of people involved in CoP proceedings with “entrenched beliefs” to be found to lack litigation capacity – with the result that they would lose the right to act as litigants in person or to instruct a legal team in CoP proceedings.

The case will now return to the Court of Appeal, where it will be decided if Poole J’s decision in January 2024 to commit Luba to prison for four months for contempt of court will stand. I would be very surprised if she keeps the same legal team.

Amongst Luba’s social media posts celebrating Mrs Justice Theis’ decision that she has litigation capacity, I found this particular one striking:

A New Chapter Begins

Today, I share this with a full heart and steady voice:

I have won.

The Court has accepted that I do have capacity –

to speak, to decide, to stand for truth,

and to fight for what is right!

After years of being silenced, doubted, and pushed to the margins, justice has found its way through.

This is not just a personal victory –

it’s a light breaking through the cracks,

a voice rising from the shadows.

I stood not just for myself, but for my daughter,

and for every mother, father, carer, and soul

who has suffered under systems too quick to judge,

too slow to listen, too hidden to heal.

This is more than a judgment.

It is a beginning.

A whisper becoming a voice,

a voice becoming a wave,

a wave becoming change…

To every one of you who stood beside me —

who believed in me when the world did not —

thank you.

Your strength carried me through the storm.

The sea is still wild,

but now the wind is with us.

Hope is rising.

We go on — stronger, together

Amanda Hill is a PhD student at the School of Journalism, Media and Culture at Cardiff University. Her research focuses on the Court of Protection, exploring family experiences, media representations and social media activism. She is a core team member of OJCOP. She is also a daughter of a P in a Court of Protection case and has been a Litigant in Person. She is on LinkedIn (here), and also on X as (@AmandaAPHill) and on Bluesky (@AmandaAPHill.bsky.social)

Appendix: Luba Macpherson’s speech to the court at the Court of Appeal hearing of 4th May 2023

Thank you for giving me the opportunity to speak.

I will begin my speech by commenting on the previous two appeals.

As you are aware the Court of Appeal has denied me two Appeals, but the Judges, Rt. Hon. Lord Justice Peter Jackson, who looked at the 06.12.22 and 30.06.2022 Orders, the same as the previous Judge Rt. Hon. Lord Baker, who looked at the 30.06.22 Orders, both showed disregard to the Law. Both of them completely ignored my “Grounds for the Appeal” document about procedural errors and multiple mistakes in Law. Both of them ignored material evidence that amounts to wilful neglect and documents such as Psychiatric and Human Rights Abuse Report, and two COP9 Emergency Applications in regards to serious medical mistreatment, including numerous Safeguarding Concerns.

Rt. Hon. Lord Justice Peter Jackson has criticised me for being “legally incoherent” in my Skeleton Argument, but he completely ignored another Skeleton Argument, prepared on my behalf by my last Barrister. He himself demonstrated that he has no respect for the Law at all. He has referred in his Order to the Court declaration in October 2020 in regards to Mental Capacity. He cannot even see anything wrong with that. He does not understand the Mental Capacity Act 2005 that it is against the Law to declare a person as lacking capacity permanently or on old statements, simply because “Capacity is Time Specific”. Both Judges also failed to see that since the October 2020 declarations, other Professionals accepted my daughter’s capacity. This was outlined in the Medical Negligence Form. I have supplied you with a lot of documents such as the Affidavits, with a Grounds of Appeal document, and the latest “Skeleton Argument” document made on my behalf by my last Barrister. I also supplied you with a bundle of 64 additional documents on which I would like to rely in my Appeal. I hope that your Honour studied them, because it would be impossible for me to go through all of them at this short hearing, but I would like to mention at least some of them.

First document that I would like to rely on in my Appeal, which I already mentioned in my correspondence with the Court of Appeal, is the latest ground-breaking judgment made on 31 of March 2023 by Lord Chief Justice of England and Wales, Lord Burnett of Maldon. In this Judgment, Lord Burnett overturned the High Court judgment of the President of the Family Division Sir Andrew McFarlane ruling. It states that: “People involved in legal proceedings be publicly identified & that people caught up in disputes with the State be allowed to tell their story or on matters of general public interest.”

That Judgement against Sir Andrew also shows that there must be no use made to prosecute because Care Staff and others may be upset. But in my case that was the reason for going to Court in the first place, and continues to be used against me when writing the Court Orders, such as those restricting access and communication and the use of a native language. Because I complained about deplorable care, and about medical abuse and about an overbearing and intimidating attitude from the Managers and inept and ignorant Social Workers, I was accused of undermining Professionals and restrictions were put in place. Please note that as soon as I was excluded from my daughter’s care, things went out of control all together. Under the Court of Protection my daughter has been abused day after day with all sorts of wrong drugs that were tried in the past and discontinued, because of their bad effect. She was twice assaulted physically. She evidently suffered from deplorable care. She suffered from psychological trauma. The Court of Protection ignored and allowed all these things and was used to persecute and punish us. It deprived my daughter of everything that is dear to her heart, all possible through perjury by the Social Workers.

The Court Orders that I am objecting to are based on lies and perjury committed in sworn statements and in Court. The first Social Worker resigned (or was pushed) as soon as she left the witness box. Her statements were not proven in fact, but relied on hearsay evidence, which would not be allowed anywhere else. Not one of her hearsay claims was backed with any statements or testimonies. She also knew what was going on regarding gaining LPAs, and the GP acceptance of full capacity, yet she then claimed to make three assessments in a week, but has kept no legally required records of them. The GP assessment was sent to the Court and completely disregarded without mention.

The second Social Worker has made statements that she herself showed to be false in her comments to her Regulators. She lied about a tribunal and she failed to adhere to the Mental Health Care Plan issued when [FP] returned against her will to Placement 1 that had been the scene of so many medication errors and mistakes. [FP] was to be returned to Hospital if anything was amiss in the first 7 days, but no action was taken on day 2 when [FP] suddenly and mysteriously became unwell. There resulted 5 weeks of screaming and PRN before readmission, with more admitted errors. The admission report showed bruises, overgrown toenails, matted and odorous pubic hair causing pain to the genital area. Is this proper care? No, it was neglect, but the Police were advised to walk away and not investigate. Why? Why were those medical records not given to the Court?

The above is only a very small portion of the huge amounts of paperwork that has been generated. Judge Poole has not investigated anything, preferring the judgments of Judge Moir who not only had a prolonged gap of three and a half months, when I was under Oath, in the case, but a bereavement and surgery before her retirement. She would not investigate missing documents, withheld documents, obvious perjury from a Carer, a lack of Statements against me, or Carers that did speak in Court for me. Yet Judge Poole has accepted that everything is above board without the benefit of seeing the wrongdoings in procedures and the errors of Judgements.

This is one of the reasons why I went public with my story, because nobody would listen and correct wrongdoings. Now, my daughter has been blocked from using her native language, and her computer and telephone, despite a Psychiatrist’s advice that it would be of utmost cruelty. She cannot pursue her love of poetry and the arts, or converse with her Russian friends at home. This is nothing short of discrimination. Where can I turn now to get the correct medication for my daughter? She was perfectly balanced in May 2020, and is now again on a known problem drug for her, and taking PRN medication to counter the effects. Why is nobody doing anything about that? A fortnightly GP visit is only allowing her torture to continue.

She was born with Cerebral Palsy, which affects her mobility, yet in five years, she has had no therapies for that. The Saunas, hydrotherapy, swimming, walking, and massage have all been put aside, and her legs have suffered as a result. This is not care as it should be! We now find ourselves with a heavily monitored once a fortnight telephone call. She is a young woman in a foreign land and she has been stripped of everything including her Mother. She is as unstable in medication as she was five years ago when I was struggling with no help. I was blamed for her condition, but nothing has changed under the alleged professional care that is sadly lacking. Yet our family has been split apart based on lies and falsehoods to protect the Council and a Council regulated Care Home. I have the documentary proof but nobody is willing to break the chain of corruption that swamps the Family Courts.

Despite the attempts to break my daughter mentally by keeping her on harmful cocktail of drugs, my daughter demonstrated her capacity all the way throughout this horrific abuse. It was shown to the Court in numerous videos and statements. Her previous Psychiatrist accepted her mental capacity. He said this to me in person. What happened next, can only be described as criminal. I will not repeat it again, because you have all of the information, including medical records and Psychiatric and Human Rights Abuse Report, but I must say that after a disastrous five weeks of wilful neglect and her readmission to hospital, all she needed was to put her Clozapine level up, but she ended up on all sorts of wrong drugs some of which were already tried in the past and discontinued, because of their bad effects. She was discharged in that unstable state to a new care home and now nobody will listen or correct the meds, despite my daughter’s and family’s constant requests. She is stuck in an engineered condition, tortured daily, crying for help, but ignored.

Judge Poole has also shown bias against me by claiming that my views are bizarre. How can he reasonably say that, without investigating the medical records that show [FP] is being given a drug that was recognised in the past as causing her problems? He has made no attempt to uncover why my views are as they are, despite material evidence and many thousands of pages of alleged evidence that should never have been accepted as credible. Judge Poole has ignored everything that was given to the Court and merely taken a stand to continue Judge Moir’s judgements without considering the background of them. Judge Poole along with every Regulator refuses to look properly at the evidence and has made an Order for Committal against me for breaking Orders that have no foundation in truth or reason. I have no means of showing my disapproval without help from the Regulators, the Police, or anybody else. So I made my comments on Social Media simply because the Confidentiality Order against me is unfair and based on false evidence. Sunderland City Council showed the same methods during the Witherwack House inquiry. Contemptible for a public body, but they refuse all scrutiny, run to Court, and remove everybody that could give evidence from the scene.