By Celia Kitzinger, 10th November 2025

Over the course of three days (20th – 22nd October 2025), the Supreme Court of the United Kingdom heard a landmark case[1], the outcome of which will affect the lives of thousands of disabled people – specifically those with cognitive impairments including learning disabilities, dementia, brain injuries and mental health issues.

Judgment won’t be handed down for some time – probably during the first half of 2026 – and it will have significant implications for the way in which “deprivation of liberty” will be interpreted in the Mental Capacity Act 2005, and for the way decisions are made in the Court of Protection in future on behalf of those deemed to lack capacity in relation to residence and care. This outcome really matters to people with disabilities, and to their families, friends, and carers, to health and social care professionals, to lawyers working with the Mental Capacity Act, and to everyone who cares about equality and social justice.

This blog post is not about the substantive issues in the case – which are amply covered in our blog posts both in advance of[2], and subsequent to, the hearing[3] – though I’ve given a very brief summary below. Instead, my focus is on how open justice played out in relation to this case. Did it work? Did it achieve what the judiciary, who aspire to transparency, hoped it would? The verdict is mixed: the practicalities worked pretty well on the whole, but the experience of observing left a sour taste for many.

In Part 1, I report the good news: that there was a more-than-usual degree of transparency in relation to this hearing. The Supreme Court was most definitely open to the public (in person and via live-streaming, and a video-recording subsequently placed on the website) and the court has also made effective efforts to make its subject matter accessible (e.g via skeleton arguments members of the public can download from the court website, and an agreed “Statement of Facts and Issues”) and to help us understand the process (via a four-page paper handout provided to those attending in person). This was all really helpful (and much more transparent than our standard experience of the Court of Protection). The judicial aspiration for transparency was supported by the Open Justice Court of Protection Project, via blogging, and a contemporaneous discussion group, with more than 150 participants, which operated over the three days of the hearing, live, as it was taking place (and continues with sporadic discussion of relevant issues). That’s open justice in action.

The bad news (Part 2) is that many of those who watched and discussed the hearing – people with specialist expertise in the relevant subject matter (the Mental Capacity Act and Deprivation of Liberty Safeguards[4]) – are dismayed by what they saw. This was true, at least, of the majority of the 150+ people who participated in our WhatsApp discussion group. This is not (or not only) because they are concerned by what they characterise as the poor level of knowledge and understanding displayed by the judges (and by some of the lawyers) and disturbed by the disablist language and assumptions displayed. They also don’t think the judges have the requisite knowledge base to understand what’s at stake, and they don’t trust that the lawyers’ submissions will have been sufficient to help them. Having seen the public hearing, they lack confidence that the judgment (when it comes) will be the right one.

This is an ironic outcome of open justice – and one not much discussed in the published judicial enthusiasm for transparency, which seems predicated on the idea that once we, the public, get the chance to see what’s going on in court, we will admire and applaud it.

Open justice is generally represented as “a principle which allows the public to scrutinise and understand the workings of the law, building trust and confidence in our justice system” (Mike Freer MP, Parliamentary Under Secretary of State for Justice – my emphasis)[5]

Ensuring public confidence in, and respect for, the justice system has long been cited as a key justification for open justice: “… in public trial is to found, on the whole, the best security for the pure, impartial, and efficient administration of justice, the best means for winning for it public confidence and respect” ( Lord Atkinson in Scott v Scott [1913] AC 417, at 463 – my emphasis)

According to Lord Neuberger, “public awareness of what happens in our courts serves to bolster public confidence in the administration of justice”[6] (my emphasis)

Lady Hale says “…open justice is there, not only to police the courts and the professionals who work in them, to ensure that they are doing their jobs properly, but also to reassure the public that they are doing so”.[7] (my emphasis)

The Chair of the Judiciary’s Transparency & Open Justice Board, Mr Justice Nicklin, says (in a published lecture[8]) that open justice is a means to an end, and not an end in itself: “it is a means to public understanding, scrutiny, and confidence”: its purpose is “the maintenance of confidence in the courts” (my emphasis).

But the outcome of open justice in this particular case has not been public confidence and respect, reassurance, or trust in the courts. Instead of bolstering public confidence in the judiciary (and the Bar), it’s undermined it. Watching the hearing was dispiriting and, at times, enraging. The overwhelming response to what happened in court is disappointment, anxiety and concern about what the judgment will bring.

We see ourselves as critical friends of the justice system. None of those involved in our Project is branding judges “enemies of the people”, imputing improper motives to the judges in this case, or seeking to impede the administration of justice.[9] Rather, in relation to this case, we are exercising a right of criticism. As was famously said: “Justice is not a cloistered virtue; she must be allowed to suffer the scrutiny and respectful, even though outspoken, comments of ordinary men”.[10]

If any part of this commentary makes its way to a Supreme Court judge, I hope there may be some benefit for them in seeing themselves as others see them. It may be that they think us wrong-headed and misguided – but the observers’ views are held in good faith, and even if we’re all wrong, there is obviously a public relations problem. The challenge for the judiciary (and, it has also to be said, for the Bar) is to learn some lessons from what happened in this case and try to ensure that open justice in the Supreme Court in future does result in increased public confidence and respect and not – as in this case – the reverse. I reflect on what might assist that project at the end of this piece.

I’ll begin with a quick summary of the case (which goes by the catchy name “Reference by the Attorney for Northern Ireland of a devolution issue under paragraph 34 of Schedule 10 to the Northern Ireland Act 1998”), before moving on to the central issues: (1) Open justice in practice; and (2) Public experience of the proceedings. Then I’ll end with (3) Reflections

Summary of the case

The case addresses fundamental issues about the way the Deprivation of Liberty Safeguards work currently in England and Wales, and whether they can lawfully be changed.

The legal question at the heart of the case (raised by way of a reference from the Attorney General of Northern Ireland[11]) is whether or not it is permissible under Article 5 of the European Convention on Human Rights (the right to liberty and security) for the law to say that a person who lacks capacity to consent to their care arrangements can nevertheless give valid consent to those arrangements if they actively express positive wishes and feelings about the arrangements in place.

At present, following the 2014 Supreme Court judgment in Cheshire West [2014] UKSC 19, the answer to that question in England and Wales is a resounding “No”.

The Cheshire West judgment found that if a person lacks capacity to decide where they live and are cared for, and if they are subject to continuous care and supervision and not free to leave, then – if their living arrangements are ‘imputable to the state’ – they are said to be “deprived of their liberty”, even if they say they like where they’re living and appreciate the way they are being cared for. As Lady Hale famously put it in Cheshire West, “a gilded cage is still a cage”.

By contrast, if someone has capacity to consent to where they live and to the restrictions placed upon them, and does in fact consent, then – even if their care involves locked doors and windows and constant monitoring to keep them safe – that’s not a “deprivation of liberty”, because they’ve consented.

Many of the people currently detained in care homes and hospitals (more than 332,000 in England in 2023/2024 according to NHS statistics) lack the capacity to consent to arrangements put in place to protect and care for them. Because there’s no valid consent, this currently constitutes a “deprivation of liberty” – and that has legal consequences in relation to Article 5 of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) .

The Deprivation of Liberty Safeguards (DOLS) are designed to ensure that the detention of people who lack capacity to consent to their residence and care arrangements is compliant with human rights. The arrangements must be the least restrictive possible, and in the person’s best interests. Although the concept of ‘best interests’ does take into account the person’s wishes and feelings, the fact that someone may be content or even happy with their care arrangements and positively wish them to continue does not in and of itself constitute “consent”.

The Attorney General is asking the judges to decide whether a non-capacitous person’s display or expression of positive feelings about their residence and care could be deemed to be “consent” – or whether that would breach Article 5.

So, if you have an impairment of mind or brain (such as a learning disability or dementia) that causes you to be unable to understand, retain or weigh information relevant to the decision about where you live and how you are cared for, can you ever be deemed to “consent” to your care arrangements? Might you ‘consent’, for example, by showing that you like the place and the people, and feel safe and cared for?

- “Yes” says the Attorney General for Northern Ireland (AGNI) and two of the interveners, the Lord Advocate and the Secretary of State for the Department of Health and Social Security. Allowing “consent” under these circumstances would comply with Article 5 of the ECHR but also avoid imputing “deprivation of liberty” to people who are happy with their care – and thereby avoid unnecessary and expensive interference in the lives of disabled people and their families, with repeated assessments that can be distressing and intrusive. The UK government goes even further, arguing that Cheshire West was wrongly decided, and urging the court to overturn it. The Secretary of State argued further that some people who are currently deemed to be ‘deprived of their liberty’ – those incapable of consenting, who cannot form the will to leave, and don’t have the physical ability to do so (e.g. people in a prolonged disorder of consciousness) should not be caught by the Deprivation of Liberty Safeguards at all[12].

- “No” say the Charities who are also intervenors in this case (Mind, Mencap and the National Autistic Society) and the Official Solicitor. Both the Charities and the Official Solicitor have intervened to argue that the concept of “incapacitous consent” is legal nonsense, in relation to the Mental Capacity Act 2005, and in relation to Article 5. A change to the law by this revision of Cheshire West would be unworkable in practice (they say), and would have the effect of denying safeguards to people who are vulnerable to harm.

1. Open justice in practice

Open justice takes work: as Mr Justice Nicklin has said, it’s “not self-executing”. In this Supreme Court case, the work was done both by the Court (and HMCTS) and by the Open Justice Court of Protection Project, and both were necessary to the successful achievement of open justice in this case.

The Open Justice Court of Protection Project is run by a core team of five voluntary (unpaid) members of the public (Daniel Clark, Amanda Hill, Celia Kitzinger, Gill Loomes-Quinn and Claire Martin: for more information about us see “Meet the Team”). Our goal is to support the judicial aspiration for transparency by observing hearings (the vast majority in the Court of Protection), blogging about them, and encouraging other members of the public to observe too. We amplify the reach of published court lists by posting them on social media and select out “Featured Hearings” for our webpage – sometimes adding a brief summary of a case or referring people to a blog post when we’ve watched earlier hearings in the proceedings. We also run regular webinars on “how to observe remotely in COP” and a WhatsApp group for observers, where people post questions and information about hearings they hope to observe. Finally, our “buddy system” provides support for people who would prefer to attend court hearings (usually remotely) in the company of an experienced observer who can help with access queries, explain the transparency order, and discuss substantive issues in the case, live, as it unfolds in real time[13]. Our buddy system can attract quite large groups of observers, depending on the case, but it’s often simply one-to-one.

The Supreme Court is much more open and transparent than the Court of Protection, so this case offered the opportunity for something much more extensive on the transparency front than we can normally achieve. Like the cases we normally observe in the COP, this case was heard in public, and it was possible to watch it in person or remotely, but there are some very significant differences.

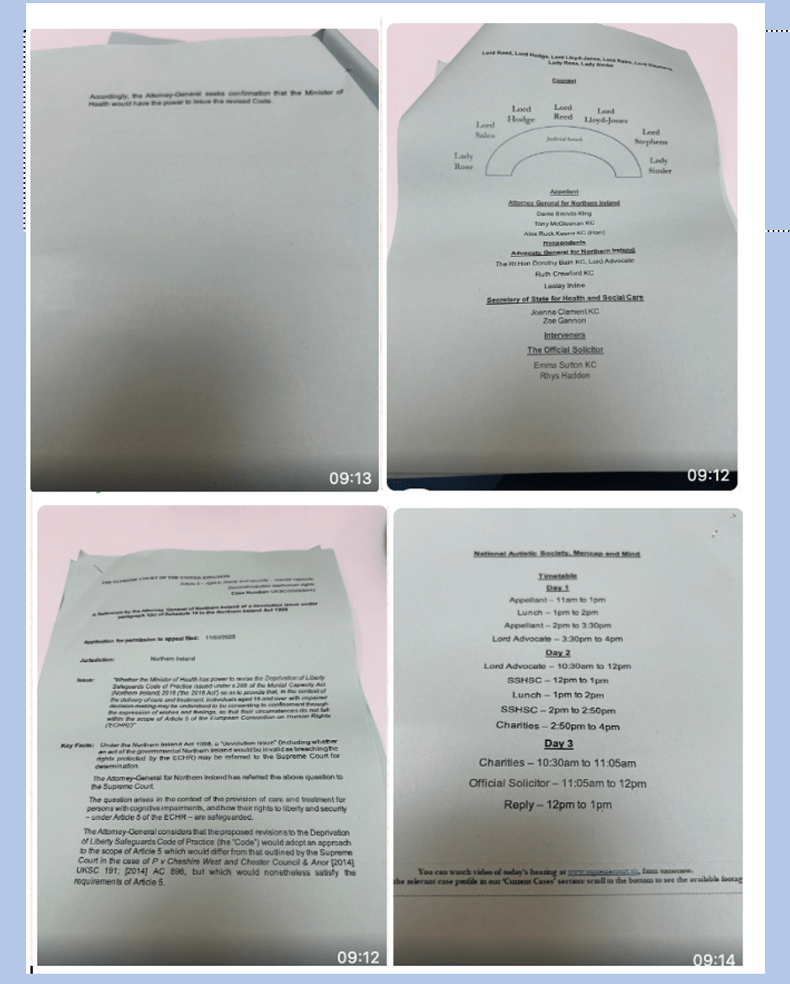

- Details about the hearing. Information about what the hearing was about was displayed on the court website months before the hearing, with a summary of the issues in the case. In the COP we usually only learn about hearings after 4pm the day before, and sometimes there’s no information at all as to what hearings are about. Where there is information, it is simply items selected from a pre-set list of “descriptors” (DOLS, s.21A, Appointment of Deputy, statutory will etc). This means, for COP cases, it can be hard for observers to plan ahead, select and to orientate themselves to cases. In addition to the advance notice and information about this case before the Supreme Court, I was impressed by the four-page paper handout provided to those who attended the court in person, which spelled out the issues, and provided key facts, plus a sketch of the seating plan at the judicial bench (so helpful in identifying the judges!), and the names of all the advocates so that we’d know who was speaking and on behalf of which party. (Identifying judges isn’t a problem in COP since there’s only ever one at a time, but discovering the names of the advocates in court and identifying who represents which party is often tricky in COP too.) The paper handout also gave the timetable for the three days – and I really don’t see why something like this couldn’t be provided to observers in COP hearings listed to extend over several days so that we can orient ourselves to the planned sequence of events.

- The hearing was live-streamed and a public recording made available afterwards. The Supreme Court of the United Kingdom was created by the Constitutional Reform Act 2005 and it has broadcast its proceedings since its inception in 2009. Live-streaming meant we didn’t need to ask the judges’ permission to observe, or request an MS Teams or Cloud Video Platform link, with the risk of nobody answering our email, or responding too late. Also, watching a live-stream is more like watching television – there’s no anxiety about being addressed by court staff or even a judge (as happens quite frequently in COP), or broadcasting a private conversation to the court by accidentally turning our mikes on. We could dip in and out of the hearing without causing any disruption. I watched part of the live-stream on my mobile phone while sheltering under Westminster Bridge during a downpour on my way to the Supreme Court! The recording is now available to view on the court’s webpage (https://www.supremecourt.uk/cases/uksc-2025-0042) – which means people who weren’t able to watch it at the time (during the working day) or missed parts due to other commitments, can watch it later. I also used the recording to check the accuracy of my transcription in writing this piece – a luxury not available to me when I report on COP hearings. There are good arguments of course against live-streaming COP hearings and placing recordings on public websites – especially given that the protected party and their family are often involved – and I don’t rehearse those here.

- There are no reporting restrictions. That’s because there’s no protected party at the centre of this case. Almost every COP hearing I’ve observed has been about the capacity and/or best interests of a particular person (“P”), who has the right to privacy. Reporting restrictions, in the form of a ‘transparency order’, are designed to ensure that observers can attend and report on the case without the risk of exposing the person’s identity. This Supreme Court case, by contrast, is an argument about a point of law.

- Skeleton arguments were posted on the court website and available to download six days before the hearing. This meant we could read them ourselves, and consider their arguments, before the case began – and for those who didn’t have time or inclination (they are lengthy and complex) Daniel Clark, the core team member who took responsibility for publicising the Supreme Court hearing, produced a summary of them[14], which turned out to be a popular option. In COP, advocates produce what are called “position statements” (effectively the same as skeleton arguments) and it is virtually impossible to obtain these in advance of the hearing. They are often referred to in oral argument, and indeed replace some of the oral argument that would otherwise be before the court, making it very hard to understand what is going on without disclosure of them. We are sometimes (but still only sometimes) able to obtain them within half an hour or so of the beginning of the hearing (but that doesn’t leave much time to read them). The barriers to getting them any earlier (especially in the face of the Official Solicitor’s now-routine refusal to disclose her position statement without being so directed by the judge) have been documented in other blog posts, and the whole issue of access to position statements has very recently (and helpfully) been addressed by Mr Justice Poole in Re AB (Disclosure of Position Statements) [2025] EWCOP 25 (T3). But we still have to email the court to request position statements, those requests quite often don’t reach the legal representatives before the start of the hearing, and we regularly encounter refusals to disclose the documents. Refusals are almost always over-ruled by a judicial order to disclose if an observer makes an oral application, but most members of the public are unwilling or unable to go through the process of challenging a refusal (as set out at §36(7) and (8) of Poole’s guidance). Even when parties don’t refuse to disclose, access to these court documents is routinely delayed by legal teams not having instructions from their clients (why don’t they anticipate that members of the public might attend public hearings and get instructions on disclosure in advance?) or by not having redacted or anonymised their statements in compliance with the transparency order (despite the guidance that “[p]arties preparing position statements should foresee that an observer at an attended hearing in public might request an electronic or hard copy and should therefore prepare suitably anonymised position statements which comply with the Transparency Order” (§36(2)). I appreciate why it isn’t possible to put COP documents on a public website in advance of the hearing, given the sensitive personal information they contain, and I also appreciate there has been a massive improvement in disclosure of position statements following Poole J’s judgment. But what a difference it makes to transparency to be able to download skeletons from a website and read them at leisure days in advance of the hearing!

This is a landmark case, affecting thousands of people’s lives: we had lots of advance warning about the hearing, no transparency restrictions, and lots of documents about the case available in advance, plus some experience of doing something like this before in the Supreme Court, albeit on a smaller scale.[16]

Amplifying open justice for the Supreme Court

Building on the opportunity offered by the Supreme Court’s much greater transparency, Daniel Clark, took overall responsibility for amplifying it. Some of the tasks involved (which make visible what it takes to make transparency a practical reality) were:

- Asking the Court for easy (or easier) read version. Celia approached the Supreme Court about this, asking whether the case descriptor could be updated so that it was easier to understand. While the descriptor was somewhat simplified in time for the hearing, it was a long way from “easy read”. (Perhaps one of the charities will produce an easy read version of the judgment?)

- Chasing skeletons. The Supreme Court’s Rule 42 states that skeleton arguments will be published a week before the hearing. After a bit of back and forth with the court, some of which implied that the court regularly doesn’t meet its own deadline, most of the skeleton arguments were published on 14th October 2025 – so six days before the hearing. Another was added two days later.

- Answering questions from the public in advance. Some of the people in the WhatsApp group had experience of observing Court of Protection hearings, and so there were some questions about how we’d be able to watch this hearing given that we didn’t need to ask for links to be sent to us. There were also some questions about whether there’d be any reporting restrictions (no) and whether we’d need to ask for skeleton arguments (also no).

- Coordinating blogs. Ahead of the hearing, we decided to publish a mix of explainer and commentary blogs. In the end we had a steady flow of blogs in the couple of weeks before the hearing, and these assisted discussion in the WhatsApp group.

- Setting up the WhatsApp group. We wanted to ensure maximum reach and advertised the group widely on social media. We decided early on to ask participants to observe the Chatham House Rule so that people could speak more freely about their opinions and experiences. Only Daniel Clark, as organiser, has waived his anonymity.

- Managing the WhatsApp group. This meant ensuring that everybody who asked for it was sent the access link, and as people joined throughout the three days, we made sure that useful information – links to the blogs, images of the handout provided by the Supreme Court, the link to the live-stream itself – was re-sent.

- Updates. After the first day, one group member suggested that a summary of the day’s argument would be helpful. Daniel was happy to oblige, initially posting it on our homepage and then turning it into a blog post that he updated each day. As expected, people were dropping in and out of the hearing and the discussion of it, and Daniel’s updating blog meant that someone who missed (for example) the afternoon of day one could still have an idea of what had happened in time for the start of day two.

Daniel explains what motivated his work on this project.

“In a speech in June of this year, Mr Justice Nicklin, the Chair of the Judiciary’s Transparency and Open Justice Board, said that “open justice is not self-executing”. I agree. In terms of transparency, the Supreme Court was close to perfect – simple access, pre-published skeleton arguments, even a pre-published statement of agreed facts. As the Supreme Court had done its best for transparency, I felt we could build on that by making the hearing even more accessible and transparent via the WhatsApp discussion group. But I have to admit that this wasn’t all about transparency. A chapter of my PhD thesis is dedicated to DoLS, so I simply had to observe this hearing, and I knew that the group would be a great opportunity to share thoughts and questions. Now I just have to think about how my thesis, which will almost definitely be submitted before the judgment, can address this case.”

On 15th October 2025, four days before the start of the hearing, Daniel set up the discussion group. People began joining and introducing themselves soon after.

Many of the 150+ people who joined our discussion group have their own strong views about the deprivation of liberty safeguards, based on professional and/or personal experience. Group participants include social workers, DOLS and best interests assessors, COP lawyers, academics, healthcare professionals who work with the Mental Capacity Act (often as MCA Leads), and family members of people who’ve been assessed for DOLS.

We wanted to hear the arguments, and the questions of the judges, as they unfolded in real time, and to be able to discuss them with others who were also invested in the decisions that the Supreme Court will (eventually) arrive at.

This is open justice and transparency in action. And, as is usually the case in our experience, we can’t rely on journalists for that: we hardly ever see journalists in the Court of Protection, and I don’t know if there were any in observing in real time in the Supreme Court (remotely or in person).

Despite its importance to a substantial proportion of the population (and potentially to all of us at some point in our lives), there hasn’t been much coverage of the Supreme Court case in the mainstream media (“The coffee cup made headlines but the fight for liberty didn’t”). Both the BBC and Sky News published pieces with headlines representing the view of the charities, prompted – I assume – by the joint press statement from Mind, Mencap and the National Autistic Society on 22nd October 2025 (“update on government legal case that has put disability rights at risk”), although they also drew on the published skeleton arguments. Other than these two articles (“Thousands of disabled people at risk from ‘back door’ law change, say charities”; “Charities warn of risks to disabled people’s rights in landmark Supreme Court case”), I’ve seen nothing in the mainstream press. The judgment, when it’s available, is likely to be widely reported, but the process whereby the judgment is reached is not.

Rather than learning about the Supreme Court’s deliberations at second-hand, filtered through the lens of the (relatively few) journalists who’ve reported on the case with heavy reliance on press releases and without attending the hearing, we wanted to have the experience of being there, in court, with the advocates, judges, and other observers – and to engage with the issues as they emerged.

In the run up to the start of the hearing

In the days prior to Monday 20th October 2025, the date for the hearing to start, Daniel used the WhatsApp group to highlight the blogs and the skeleton arguments.

On the Saturday, there was a surprise announcement from the government: it was launching a consultation exercise about the long-awaited Liberty Protection Safeguards. I posted that on the WhatsApp group too.

There were some sceptical responses about the timing of this announcement (at the weekend, just before the beginning of a Supreme Court case on the Monday) but one more charitable participant commented:

Early on the Monday morning, Daniel reminded everyone of the benefits of doing some advance preparation:

Quite a lot of people had joined the link over the weekend (and the numbers steadily increased over the course of the three days of the hearing). For many of us, there was a lack of clarity both about where the link would be posted and what time it would start. (The Court could usefully help with both of these issues in future.)

One contributor had been informed that the hearing would start at 10.30am, but another said one of the advocates had told him it would be 11am (which turned out to be correct).

And someone attending court in person (not me, I hadn’t arrived yet) had found the 4-page handout, and photographed it for people observing remotely. That was enormously helpful – but couldn’t it have been placed on a Supreme Court webpage please?

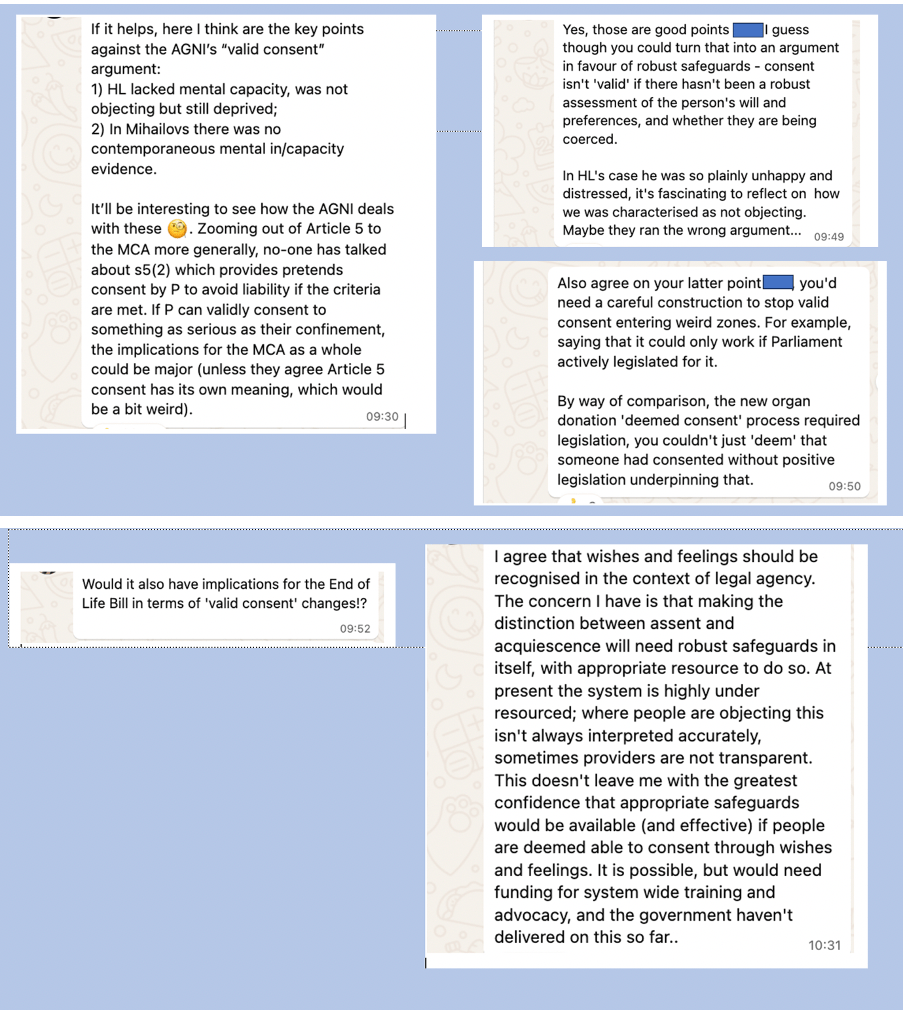

And while we were all waiting, people began to discuss the substantive issues of the case.

At 10.18am, someone spotted that the link to the hearing had been made available and posted it for all of us.

Then, on the dot of 11am, the court rose.

Access challenges

Participants observing remotely experienced problems with the volume – it was “very quiet” and sometimes “dips in and out”. Turning up the volume on our laptops helped. It was frustrating not to be able to turn on subtitles on the livestream (you can on the recorded version) and that raises access issues for Deaf people and those with hearing impairments. A few participants were also still looking for the link.

I was observing that day at the Supreme Court in person – and that was a generally good experience, that compared well with my experience of in-person observation at other courts. There was less of a queue than at the Royal Courts of Justice to get through the usual airport-style security. Staff were able to direct me to the right courtroom – and despite the warnings on the website, there was no objection to my using my laptop in the courtroom (many other people had theirs out too).

The main problem with in-person attendance was terrible sound quality on the first day. I simply couldn’t hear from the back of the court. When I complained to court staff, I was advised to sit in Court 2 which was live-screening the hearing from Court 1, but that would have rather defeated the purpose of being there in person. I also mentioned the problem to a couple of the lawyers (one of whom said she was struggling to hear too), and the following day it was somewhat improved – although even the judges occasionally had problems (Lady Rose to Lord Advocate: “I’m so sorry can you keep your voice up – I’m struggling to hear when you’re facing that direction”, 14:30 21st October 2025 morning session).

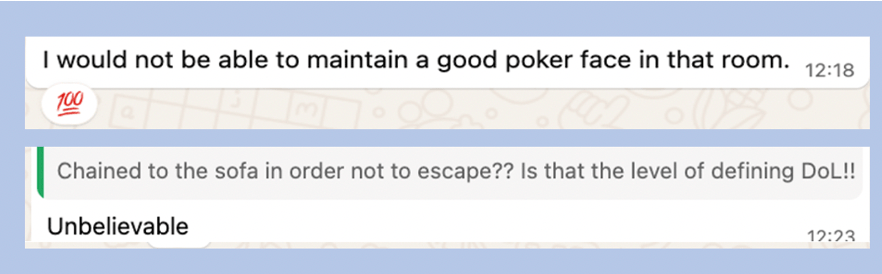

As always, the in-person court observer, sitting toward the back of the room, has a distant view of the judge(s) and can only see the backs of the advocates’ heads. It’s obvious from the online discussion (and, later, to me when viewing via the link) that remote screening provided a much more up-close-and-personal viewing experience. I missed the “side eye” from Lady Rose, and didn’t see Alex Ruck Keene apparently “bobbing up and down”. The advocates had their backs to me, and most of the time I couldn’t see the judges (and certainly not anyone in the row behind the judges) because the judges are not on a raised dais, the seating isn’t raked, and I was sitting behind people taller than me who were obscuring my view. I admired Lady Rose’s brooch (commented on in the chat) once I reviewed the recording but it was way too far away to appreciate in the courtroom! In terms of the quality of the observation (listening and seeing the court), the online experience is vastly superior[17].

Nonetheless, to be in the Supreme Court in person for a historic case –to be able to say “I was there on that day” (as someone put it) – “in the room where it happened!” (another responded) – was exciting and some of the remote observers expressed envy that I was able to be there is person. Another in-person observer shared images from inside the building (we weren’t allowed to photograph the hearing in progress):

Courts are public buildings, and this one (unlike most) seemed to function as such. It’s a minor tourist attraction, after visiting the Houses of Parliament and photographing Big Ben. During the time I was there over the course of two days, I spotted at least three different student groups visiting the lower ground floor exhibition and the café, and one group of about a dozen young people filed into the hearing and stayed for about 15 minutes before being led out again after experiencing the Supreme Court in session. The exhibition has short educational videos on continuous loop (e.g., on the separation of powers) and the illustrative cases are designed to appeal to public interest (e.g. treatment withdrawal, assisted dying, civil partnership). It’s less grand and austere than the RCJ, less ‘bureaucratic’ than First Avenue House, and not at all shabby and depressing like many of the decaying regional courts. I’d recommend a visit.

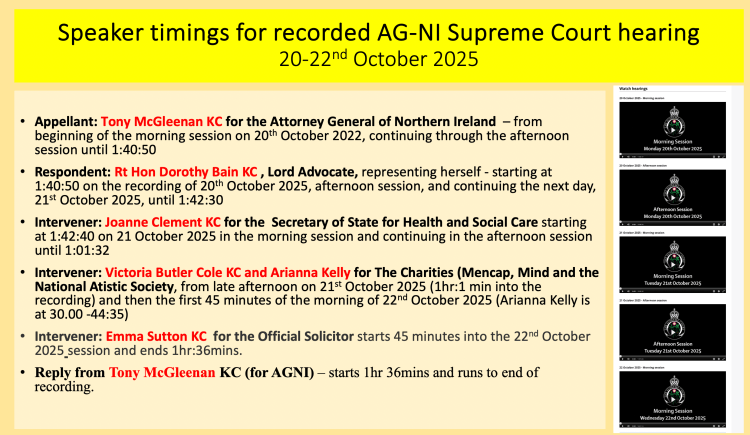

After the proceedings, people who’d missed observing at the time were keen to watch the recordings, and others wanted to listen again to particular parts. I made this slide (below) to help people locate particular speakers on the recording, and it may be useful to readers of this blog post too, in providing an orientation to how the hearing was organised.

2. Observers’ experience of the proceedings

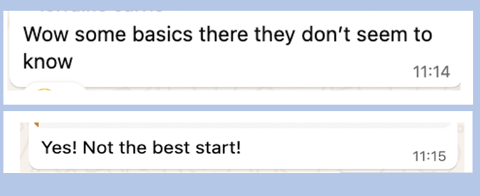

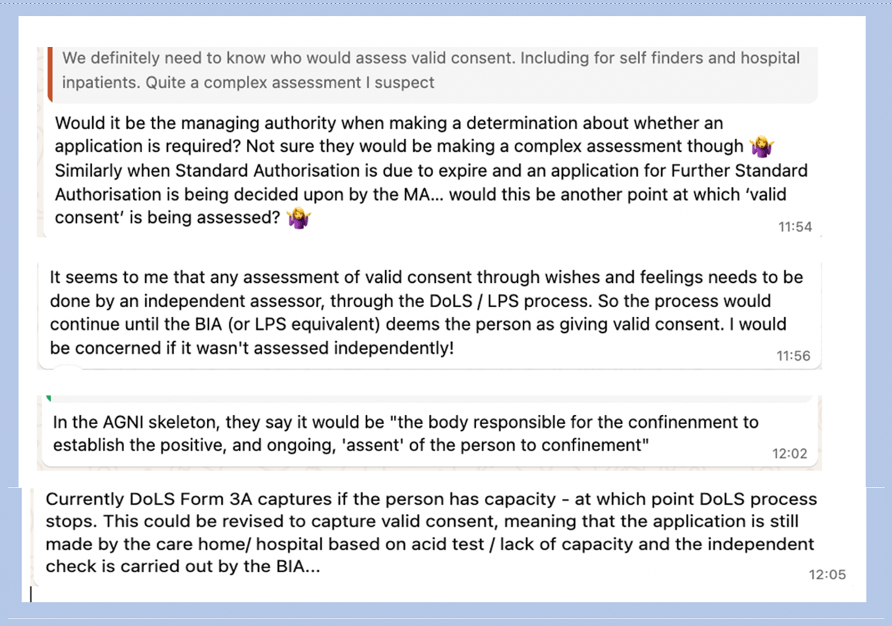

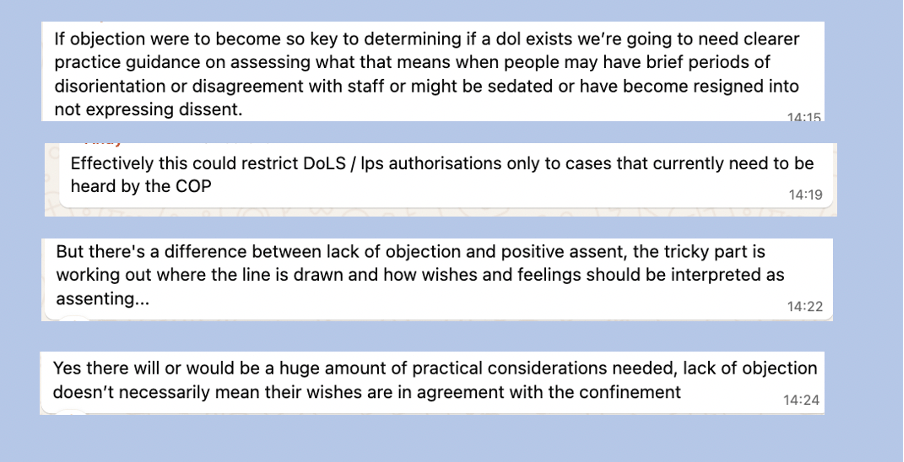

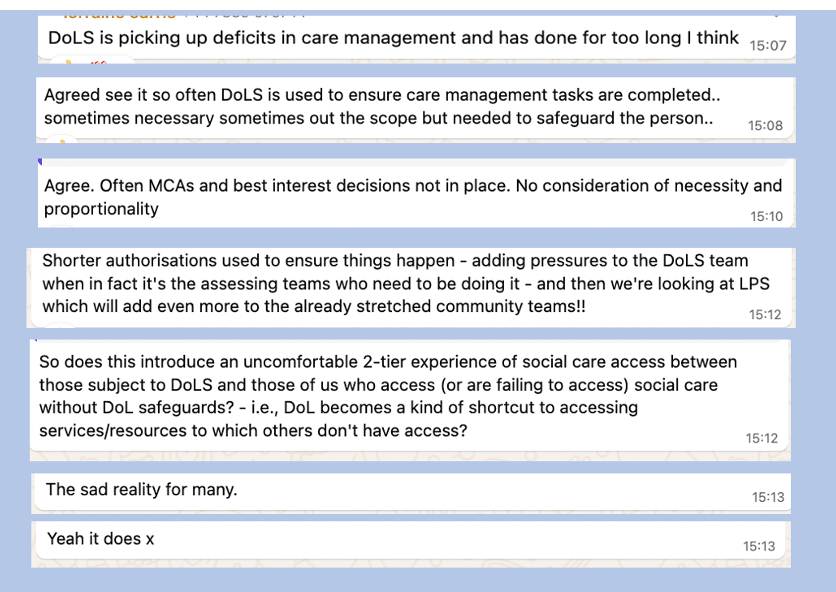

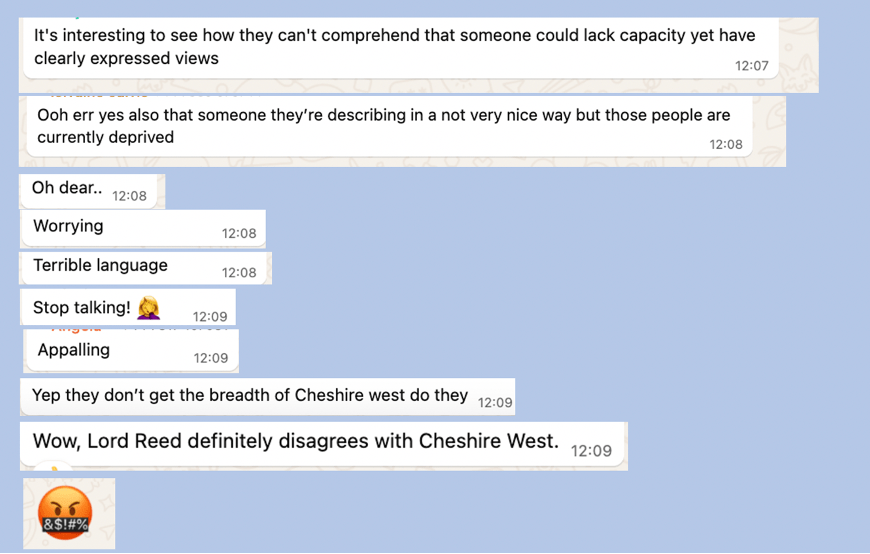

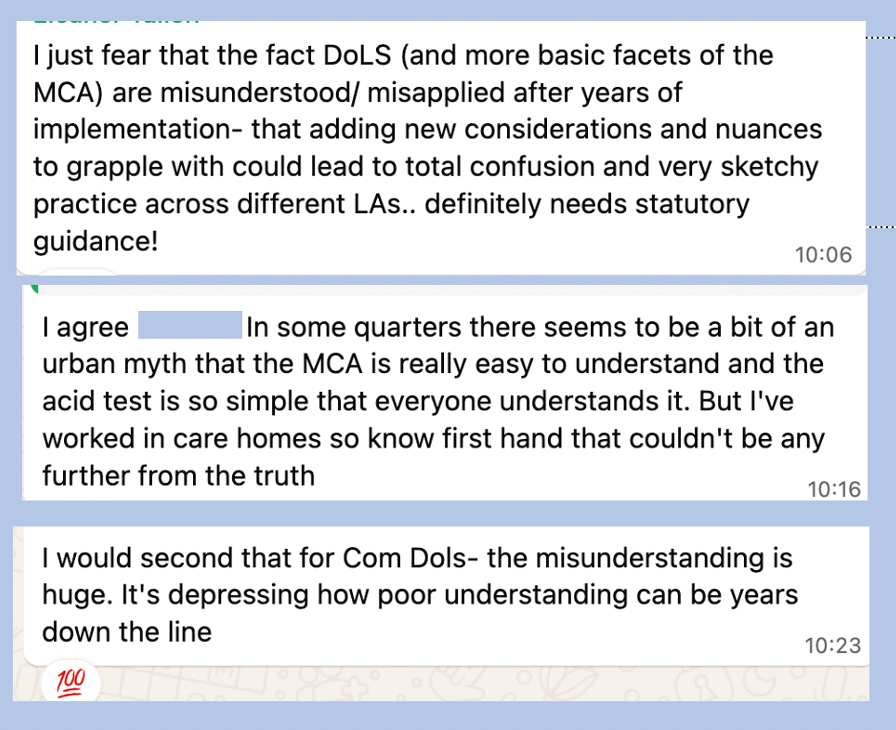

The sense of excited anticipation that characterised the build-up to watching the hearing subsided fairly quickly once proceedings began. It became apparent that there was a significant gap between the observers’ professional and experiential knowledge about the Mental Capacity Act 2005 (and Deprivation of Liberty Safeguards) and the legal theory being discussed in court. The discussion group comments reflect increasing dismay – and commentary about the hearing cascaded out of our private WhatsApp group onto social media.

Social worker and experienced Adult Care Manager, Tilly Baden, who has ‘outed’ herself as a member of our Supreme Court observers’ group in her article for Social Work News, reports that over the course of the three days, observers “veered between disbelief and gallows humour. The collective feeling was one of weary frustration”.

“It often felt like an out-of-touch seminar on the theory of umbrellas while the rest of us were standing in the rain. There were points where you couldn’t help wondering whether some participants had ever set foot in a care home, spoken to a best interests assessor or even – *shock horror* – met a person actually living under restrictions. […] While the heavyweight legal parties flexed their procedural muscles, those who live and breathe the Mental Capacity Act were almost invisible. No frontline workers, no family carers, no advocates. Just a roomful of wigs[18] dissecting the philosophy of liberty as if it were a word puzzle rather than a lived experience.”[19]

This doesn’t tell the whole story of our experience, but it’s certainly a significant part of it. We were repeatedly surprised by what the courtroom actors appeared not to know about the way the current law works, in the daily experience of many observers.

The exceptions were undoubtedly Victoria (Tor) Butler-Cole KC (for the Charities) and Emma Sutton KC (for the Official Solicitor) – both of whom regularly appear in Court of Protection proceedings and have an excellent grasp of issues on the ground. Both pointed out that because of the way this case has reached the court – as a Reference – “you have no real-life examples of these hypothetical people who simultaneously lack capacity to consent to their care arrangements, but can nevertheless give valid consent to them for the purposes of Article 5” (Tor Butler-Cole’s words). Emma Sutton KC likewise drew attention to the absence of real people at the heart of this case and sought through evidence placed before the court to “bring the abstract to life”. Her “case studies” wove human stories with legal argument to make the case against the AGNI’s and SOS’s proposals, and humanised the issues with concrete examples of the dilemmas and contradictions that would be created if the AGNI’s proposals were adopted – cheered on by the observers in our discussion group. Both lawyers impressed observers with their clarity and the sense that they were in touch with how processes actually work. Their submissions were rooted in practical hands-on experience with DOLS in real cases.

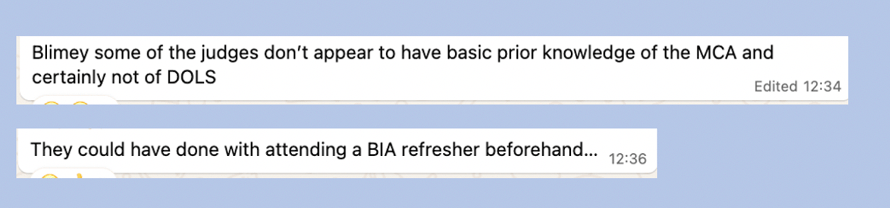

But the overall experience of observers was that key players, the people with the most extensive input into the hearing – the judges, and counsel for the Attorney General of Northern Ireland (AGNI), counsel for the Secretary of State, and the Lord Advocate – did not really understand the way things work at present, and were not in a good position to appreciate the risks and benefits of the changes advocated in this case.

I’ll illustrate the concerns expressed by observers as they unfolded in the order in which submissions were given. In what follows, I’m not attempting to summarise the arguments of the parties (you can read the skeleton arguments on the UKSC website and the “summary” blog post for that), but rather to show how the public observers responded to what they were hearing.

The proceedings got off to a bad start when Tony McGleenan KC (counsel for the AGNI) introduced the case. He said: “The focus of the case is on the phenomenon of social care detention wherein many thousands of people with diminished mental capacity who are resident in forms of social care placements, which might be residential homes, care homes, assisted living placements or even in their own homes, are considered to be deprived of their liberty for the purposes of Article 5 of the Convention.” (05:30, 20 October 2025, morning session)

One observer immediately picked up on the omission of hospital care in considering DOLS (it was discussed by the court later).

One of the judges, Lady Rose (generally considered most ‘on the ball’ by observers) tried to unpick a different problem with the AGNI’s version of “the focus of the case”: the inclusion in his list of places of confinement to which Article 5 might apply of “in their own homes”. It doesn’t – at least not in England and Wales. Perhaps it does, she queried, in Northern Ireland.

Rose: This [DOLS] in England and Wales is for (pause) care home and hospital?

AGNI: Yup.

Rose: But are you saying this is the process in Northern Ireland, which I don’t think has that same distinction between deprivations of liberty in care homes and hospitals and other deprivations of liberty?

AGNI: The reach is wider in the Northern Ireland legislation.

Rose: Yes, so is this the process that applies in Northern Ireland more generally even if it’s not in a care home or hospital?

AGNI: Yes, the broad concepts apply in Northern Ireland, but I’ll show you there’s a greater reach. And there are some other material differences. That’s just to sketch the issue to the court. (13.07, 20 October 2025, morning session)

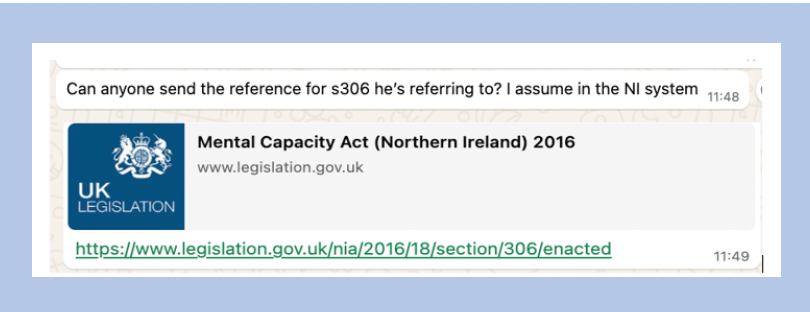

Lord Reed tried again, raising the question of the precise reach of DOLS in Northern Ireland, and indeed perhaps in England as well – rather a key issue for this hearing! It was Alex Ruck Keene KC (Hons) (ARK) – “junior counsel” for the appellant, who provided the court with the right answer.

Reed: Is DOLS applied more widely in England and Wales to cover cases like MIG and MEG, where someone isn’t in a care home?

AGNI: That’s what we understand to be the case, My Lord, yes.

ARK: (whispers to Tony McGleenan KC [AGNI])

Reed: So while this process refers to the care homes and hospital, it in fact is applied more widely, not just in Northern Ireland but also in England and Wales?

AGNI : Yes. Yes. That’s by way of sketch of the position, generally. Can I take you to the Northern Ireland statutory scheme which I-

Reed: (interrupts) You’re about to be corrected by your junior.

ARK: (more whispering to Tony McGleenan KC [AGNI])

AGNI: According to Mr Ruck Keene, outside the care home arena, there’s a court order procedure that’s required.

Reed: The Court of Protection?

AGNI: Yes.

(13:43 20 October 2025, morning session)

As observers commented:

I don’t want to give the impression that criticism of the court actors was the dominant theme of the discussion – it wasn’t. Most of the time people were seriously engaged in trying to follow the arguments and get to grips with how the alternatives that were being proposed to the current DOLS system, as defined by Cheshire West, would actually work.

There was some discussion of the alternative framework in Northern Ireland.

Some observers recognised the force of the arguments counter to Cheshire West raised in High Court judgments from Mostyn J and Lieven J – both of which were overruled in the Court of Appeal with what the AGNI described as a “fairly firm rebuke”. Some observers accepted that this has led to “an ossification of a line of authority that can’t be overturned” (AGNI, 1:35 20th October 2025 afternoon), which is why the issue is now before the Supreme Court as a Reference and not as an Appeal. Nobody suggested that the system is working well as it stands – but proposals for change need to be rooted in an accurate analysis of what the problems are and how to fix them on the ground.

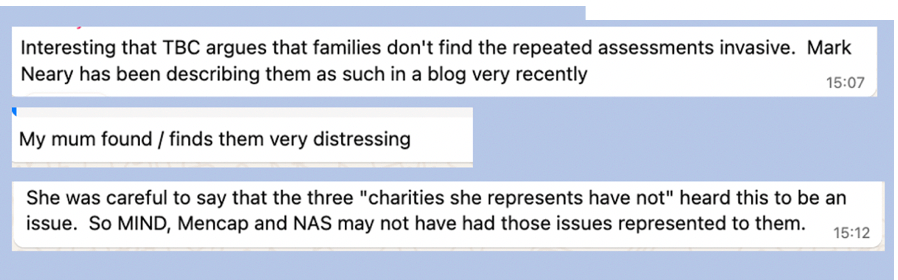

Later, the comment from counsel on behalf of the Charities that there is no real evidence to suggest that people experience DOLS assessments as intrusive also attracted attention. People drew attention to blog posts from some family members who do[20] experience the DOLS process as intrusive, and to this post on X from Mark Neary which shows his son leaving the house to go shopping, buying his purchases and returning home – by way of lampooning the applicability of the concept to his son’s living arrangements. (Mark Neary was also referenced by the AGNI)[21]

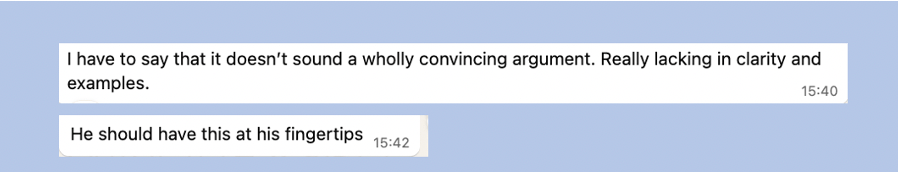

Observers became increasingly frustrated at the lack of clarity and detail in the submissions from the Attorney General of Northern Ireland.

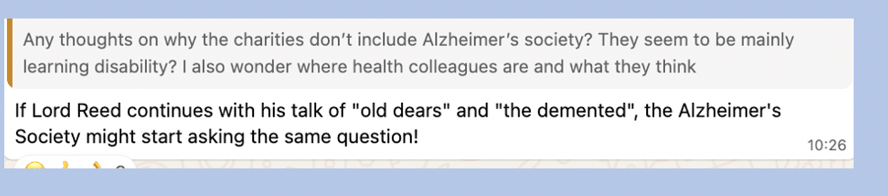

The language used to refer to people who may lack capacity to consent to their care arrangements was a recurrent concern that surfaced initially in the course of the Appellant’s submissions via a question as to whether a subcategory of people currently affected by DOLS – those unable to recognise any confinement and restrictions, incapable of forming an intention to leave, and physically unable to leave in any event – were actually “deprived of their liberty” in the sense required by Strasbourg jurisprudence. This line of questioning was quite confusing and would more properly have been directed to the Secretary of State (whose proposal it was to exclude them from the Deprivation of Liberty Safeguards) – and the terminology used was at best uninformed and at worst explicitly derogatory:

PVS, demented, catatonic people and ‘old dears’

Reed: I find it very difficult to understand in what sense a person who’s unable to form a wish to leave somewhere, and may also be physically unable to do so, can be said to be deprived of liberty at all. (puzzled tone)

Hodge: Yes, I was going to (laughs) raise that point. Is the Strasbourg jurisprudence saying that such a person is deprived of liberty?

Reed: I mean, if you have somebody in a persistent vegetative state[22] in the home, is that person being deprived of their liberty? Surely not. If they’re not, what about somebody who is so demented they’re effectively catatonic. Just spend the day in front of a television set. Is that person- In what sense does that person have any liberty which she can be deprived of?

AGNI: That’s why it’s important- I probably flashed across it too quickly, but when you go back to Guzzardi, Guzzardi[23] emphasises that what’s in play is physical liberty. That’s what Article 5 protects – physical liberty. So, if an individual is in a PVS state – immobile, unable to communicate – it’s difficult to see how there is a restraint or a deprivation of physical liberty in that context that engages the whole machinery that starts the process off. So, My Lords….

Reed: What about the old dear who is simply got out of bed in the morning, given a- washed, and put in front of a television until it’s bedtime. (Shrugs and shakes head from side to side as if in disbelief). I mean, what liberty does that person have to be deprived of?

AGNI: Again, on that analysis you significantly narrow the cohort of individuals who’d ever be caught by the Deprivation of Liberty Safeguards.

Reed: Well, that may be.

Rose: Well, how are they treated at the moment? Are the people posited by my Lord, Lord Reed, treated as if…

AGNI: There’s a deprivation of liberty.

Rose: They are treated as deprivation of liberty cases. And your proposed revised guidance wouldn’t affect that?

AGNI: Not in the cases where there’s an inability to express any wish. It wouldn’t necessarily affect that.

Hodge: Well then it comes back to the question, is there Strasbourg jurisprudence which supports bringing these people within Article 5?

AGNI: Not expressly, My Lord.

Hodge: Well on what basis is the domestic law, given that it’s tracking jurisprudence on Article 5, applying a deprivation of liberty regime to them?

Not long afterwards, Lord Stephens referred to people who are “drugged up” and “suffer from Alzheimer’s”; Lady Rose raised a question about a hypothetical person “chained to the sofa” to stop her from leaving (1:14); and then Lord Reed summoned up “the bedridden person who is physically incapable of leaving the hospital”. In the afternoon of the same day, counsel for the AGNI referred to “catastrophic dementia” (1:38) and the theme of “catatonic” dementia[24] was picked up on the last day of the hearing by Lord Sales[25].

I recognise that this focus on the permanently unconscious, catatonic, catastrophic, seriously demented and bedridden was designed to test the proper scope and limits of the concept of “deprivation of liberty” in Strasbourg case law – and it goes to the heart of one of the issues before the court. But the language used was ill-advised and contrary to guidance put out by the relevant charities and professional bodies[26]. It felt discourteous to the people the judges were referring to, and it evoked a visceral response in many observers that made it impossible to focus on the substantive issues at stake. In a blog post afterwards, Mental Capacity Consultant, Lorraine Currie[27] said she was “horrified”. On X, Court of Protection and Community Care specialist solicitor Zena Bolwig said she also “recoiled at the language used a number of times”. On LinkedIn, consultant clinical psychologist, Dr Catriona McIntosh found it “shocking” [28] and a legal professional with more than a decade of COP experience responded to say she was “taken aback”. Also on LinkedIn, the open justice legal commentator, George Julian, said “after watching 1.5 days of the case if I were a Supreme Court judge I’d like to think I’d have a word with myself about my internalised ableism and how readily prepared I am to demonstrate that to anyone watching. Some of the language and phraseology I found eye-popping“. Our discussion group members were frankly appalled.

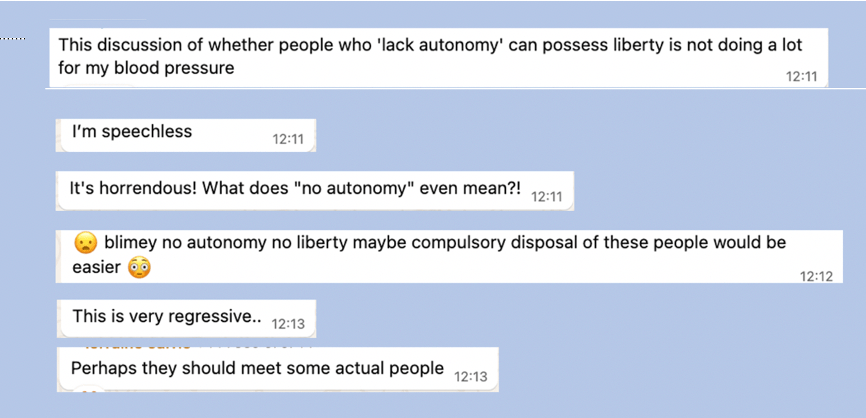

The next morning, while people were waiting for the hearing to start again, there was this exchange:

A little later in the proceedings, Lord Reed tried to shed light on how best to address the matter and said, “ I mean one way of putting it is to ask whether a person who lacks autonomy is capable of possessing liberty, within the meaning of the Convention.” Again, I appreciate that this is a “way of putting it” that goes to the heart of the question before the Court, but it didn’t go down well with the observers.

It was reassuring to see Emma Sutton KC (for the Official Solicitor) address Lord Reed’s point (as she put it) “head on” on the final day of the hearing. My understanding is that, under the circumstances, this was a “brave” thing to do, and it was commented on by COP solicitor, Jess Flanagan, on LinkedIn.

Here’s what Emma Sutton said: “I’d like to address the point, head on, raised by Lord Reed on Monday – I think it was – that people with significant cognitive impairments do not have liberty to lose. And I would invite the court to be extremely cautious before reaching that conclusion, having regard to the universality of rights. But perhaps more importantly, that requires a type of medical approach that P has no subjective experience of the world at all – and that’s an extremely difficult conclusion to reach, but for unconscious or minimally conscious states, so the cases of Ferreira and the case of Briggs.” (1hr 10mins and 34 seconds, Wednesday 22nd October 2024).

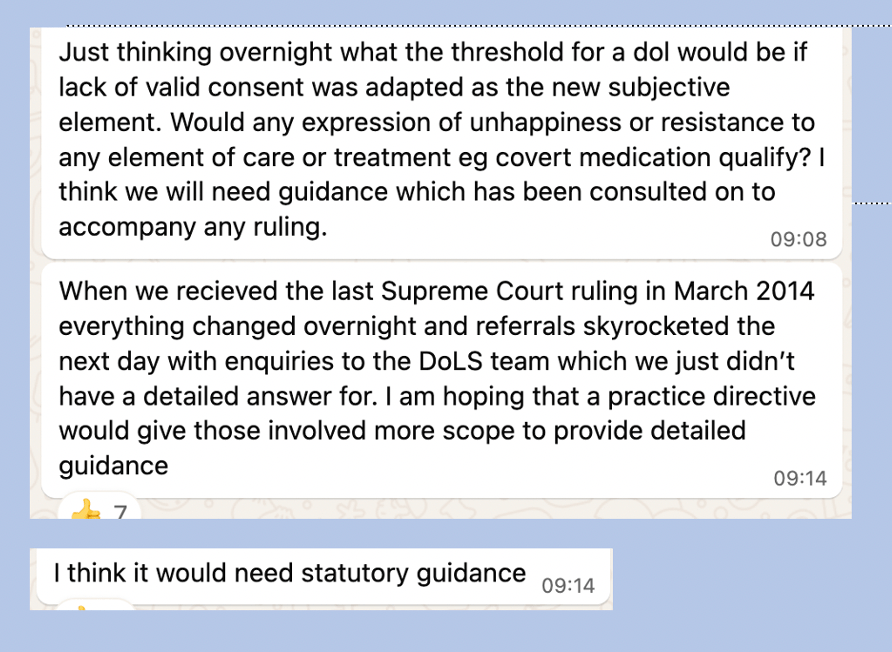

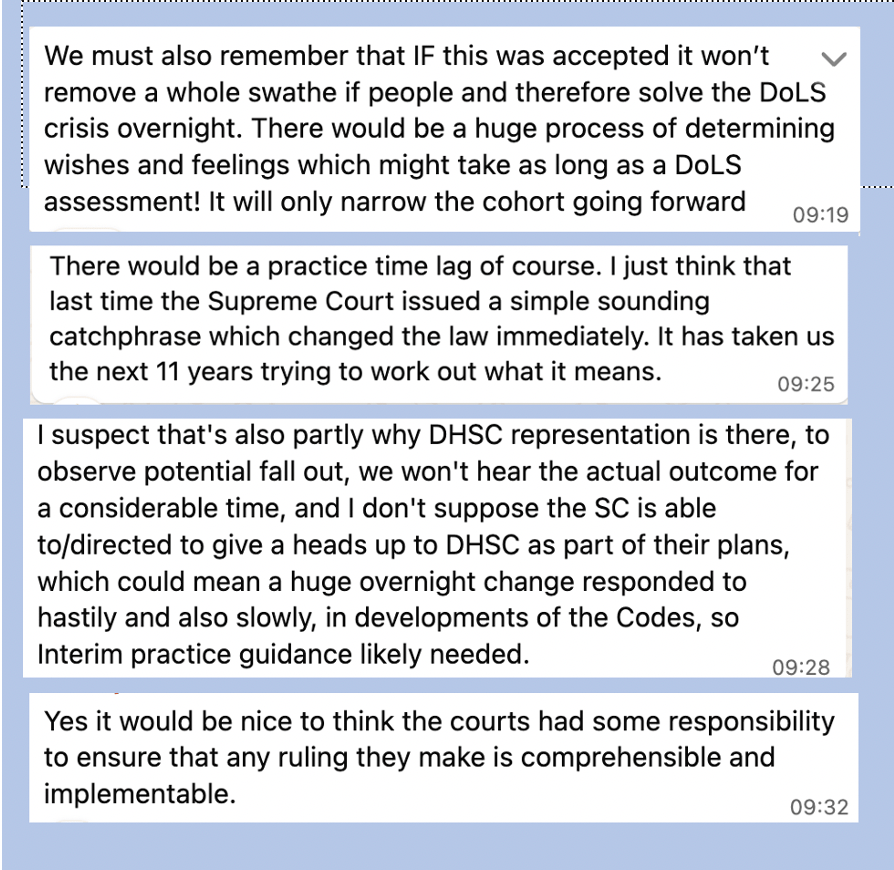

By the end of the AGNI’s submissions on the afternoon of the first day, observers were deeply frustrated and concerned too about the practical implications, which were discussed in advance of the beginning of the second day’s proceedings.

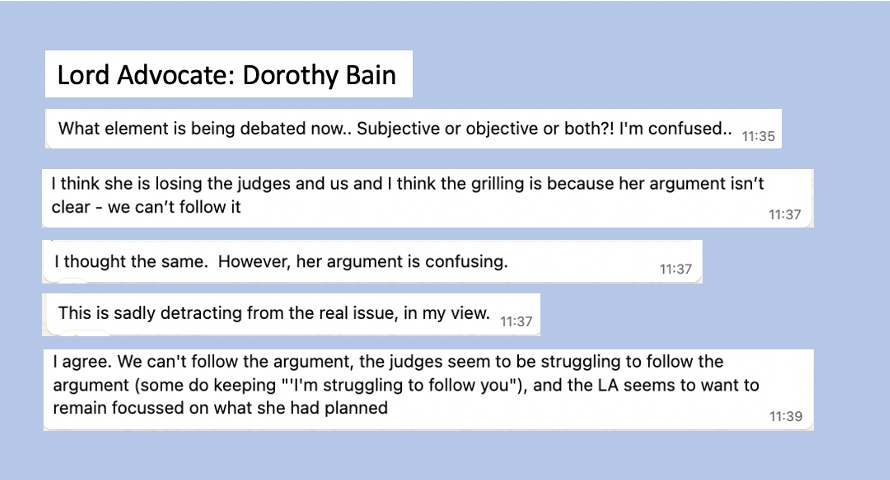

The Lord Advocate[29], who spoke on the second day, did not help matters. She is the principal legal adviser of both the Scottish Government and the Crown in Scotland for civil and criminal matters that fall within the devolved powers of the Scottish Parliament. Her submissions were experienced as muddled and confusing. She was trying to read from a text, but was frequently interrupted by the judges who, like us, seemed also not to be able to follow her line of argument – and, as some of the observers commented, the judges’ sometimes rather sharp interventions felt “uncomfortable” and “like a grilling”.

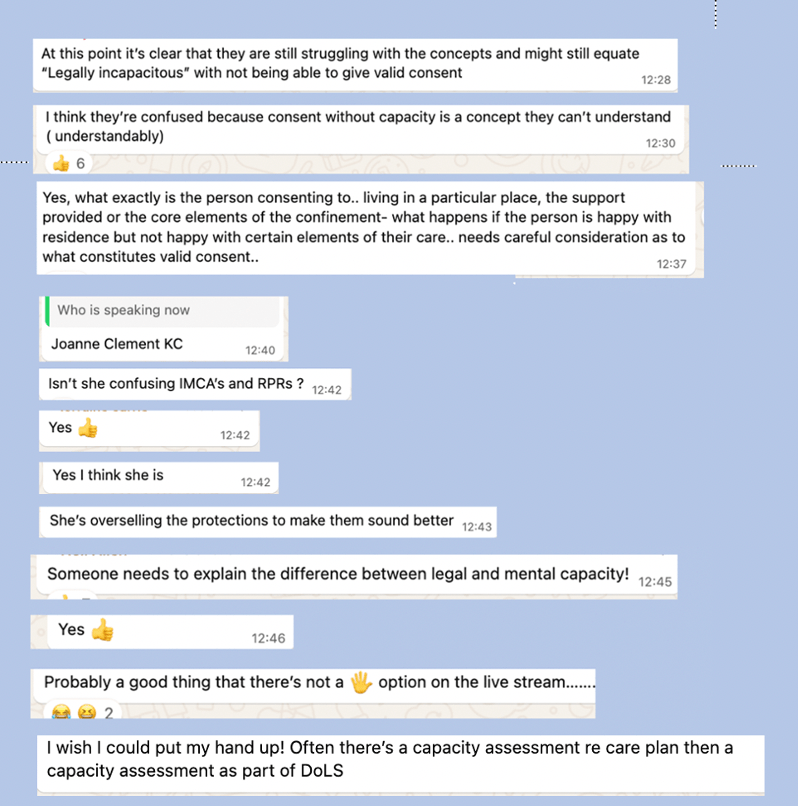

After the Lord Advocate, the counsel for the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care[30] made confident submissions but she was not (said the observers) always correct – and the judges remained (they thought) “confused”.

As counsel for the Secretary of State was speaking, the observers found themselves shouting the correct answers at the screen, or wanting to raise their hands to provide accurate information.

Counsel for the Secretary of State was followed by Victoria Butler-Cole KC for the Charities, By around half way through her submissions, the observers were losing patience with the judges again – especially at the point at which first Lord Stephens and then even more painfully, Lord Hodge, appeared not to be aware of the Mental Capacity Act’s definition of “capacity” as requiring an ability to “understand, retain and weigh” information relevant to the specific decision that needs to be made (1:30-1:31:34). Counsel explained it all, without a hint of impatience – while observers were posting palm-to-face emojis and asking “How do they NOT know the functional test?!”, “Oh god. They are being taught the MCA”; and “Surely this lack of knowledge and understanding should preclude them making a decision?”. Some of us tried – either then or later – to put a positive spin on what looked like judicial ignorance. Maybe they were just wanting to put the facts and the law “on the record”. Maybe some of Lady Rose’s questions (like her enquiry about what exactly a “care package” is, at 1:06:50) were designed to ensure that her fellow judges were exposed to the information she thought they needed, but she already knew? Maybe they’ll “catch up” with what they should have known before after the hearing?

3. Reflections on open justice – the outspoken comments of public observers

So, coming back to where we started: “Justice is not a cloistered virtue; she must be allowed to suffer the scrutiny and respectful, even though outspoken, comments of ordinary men”.[31]

It took a lot of work from the Open Justice Court of Protection Project to support members of the public to observe this hearing (“I would not have known how to watch if it wasn’t for you”) and to support informed engagement with the case – via blog posts introducing the issues before the court and by hosting a public forum for discussion. Observers were mostly health and social care professionals working with the Mental Capacity Act – plus some lawyers and some (like me) family members of people who lack capacity to decide about care and residence. There was an expectation that watching the case would be educational and improve practice: a couple of participants told me they had negotiated Continuing Professional Development points for the exercise. We were excited by the prospect of watching “the brightest legal minds in the country” (as one participant referred to them) address the problem of DOLS. But overall, watching the Supreme Court in action left people “shocked”, “disillusioned” and “devastated” about the workings of the justice system in this case. For example, in emails to me after the hearing people said this:

“I was utterly shocked by their complete ignorance of the basics. It felt rude and disrespectful to thousands of vulnerable people that they had not bothered to read something on what the MCA is before commencing their involvement in life changing decision-making. I expected evidence and questions to fine tune their knowledge, not for it to be addressing the basics I would be covering with my students.”

“I feel very disillusioned with the quality of the court’s understanding – both the advocates and judges…. It’s interesting to contrast this with the debates in Parliament over the Mental Health Bill – where the level of in-house understanding and expertise is so much higher. I guess that’s why people say that Parliament, not courts, should legislate for these serious matters”.

“As a social worker of longstanding, a BIA and manager of a team undertaking COMDOLS, I was quite devastated by what we heard at the SC last week. The depth of the misunderstanding by some of the judges about MCA basics, about the reality of the lives lived by those who meet the acid test, and about the limitations of our depleted and exhausted care system hurt to hear.

With my work hat on, I have seen too frequently the restrictions that have become invisible, the management strategies where convenience rules, and the damage to rights caused by unchallenged “custom and practice”.

With my home hat on, I have seen my father this summer spend 6 weeks in hospital after a fall, followed by 16 days in a nursing home with no DoLs – not because he didn’t merit this but because the overstretched DoLs team did not get to him. And so, his door was shut because he kept wandering, his walking aid was kept the other side of his room and his bed lowered so that he did not get up for the toilet when unsupervised. I have seen my son (who now has excellent care with a great provider), prevented by previous providers from drinking so he didn’t wet the bed while seizing, and restrained using techniques not recorded or subjected to BI and prevented from entering certain areas of his accommodation.

The system is overwhelmed, we all agree. But fixing it must not be achieved through watering down the protections that are so vital for those they are designed to safeguard. The voices of professionals working with the MCA every day were missing last week just as were the voices of Ps and their families.”

The comments above are not attributed to individuals because most people feared professional repercussions – from employers perhaps, or from judges before whom they may be making submissions in future as advocates or giving evidence as expert witnesses.

Open justice, says the Lord Chief Justice, “requires those present at a hearing to be able to discuss, to debate, and to criticise what was said and done by the parties and the judge, and even the judgment”[32] But it’s remarkable how few of the lawyers, scholars and experienced practitioners in this field feel able and willing to put their names to explicit criticism of what they’ve witnessed or to respond, frankly, in public, to what judges have said. Without feedback of the sort in this blog post, I suspect that the lawyers and judges would have no idea how the public responded to what they saw in the Supreme Court – and therefore no opportunity to repair the damage, e.g. by addressing these issues in the published judgment and by finding ways to avoid these criticisms on the next occasion.

The judges (and some of the lawyers) need to know that they (unintentionally, I’m sure) displayed what many observers experienced as discourteous and uncivil attitudes to people with disabilities, and a rather cavalier approach to the day-to-day realities of these people’s lives, and the lives of their families and those who care for them. I hope that this blog post enables them to see themselves as others see them and thereby perhaps to generate for themselves some ideas about how to create a more positive image of the court in future.

Even if they think our views of what went on in court are wrong, or muddle-headed or the result of our misunderstanding the proceedings – still there is a problem that needs to be addressed. That’s because open justice, the purpose of which is to build trust and confidence in our justice system, has had the opposite effect in this case. Instead of bolstering public confidence in the judiciary (and the Bar), it’s undermined it. Open justice has backfired, and this should be of grave concern to the court.

We recognise that there are only 12 Supreme Court judges to hear all the cases that come before the court, and that they can’t be experts in everything. On the basis of this hearing, there’s a shared view that we desperately need a judge with experience of the Court of Protection (or Family Division) in place before another case relating to mental capacity or DOLS reaches the Supreme Court. Lord Richards is retiring in June 2026 but the vacancy has been advertised for someone with “substantial experience in equity and corporate law“. We hope that the next vacancy can be reserved for someone from the Court of Protection or Family Division.

Until then, we ask these judges – who are highly educated (6 of the 7 have Oxbridge degrees) and highly paid (their annual salary is £254,274) to explore what it would take to create a better impression on the public. One suggestion might be more pre-hearing preparation. In a lecture on “working methods of the Supreme Court”[33], Lord Burrows says that he usually spends “about a day” in advance of a hearing reading “key documents”, followed by a brief (15-minute) discussion with fellow justices to discuss “procedural matters and our preliminary view of the case”. In an area of law in which none of the judges has any prior experience, this doesn’t sound nearly enough!

We don’t want grandstanding from counsel, or judges playing to the public gallery – but we do think they need to be a bit more aware of the values and principles that members of the public bring to hearings (whether or not they share them) and conscious of the subject-specific knowledge and experience that informs us (of which they may know little or nothing).

For our observers’ group, the experience of open justice in the Supreme Court has backfired and the Court now needs urgently to consider what they can do build public confidence in the justice system.

Celia Kitzinger is co-director of the Open Justice Court of Protection Project. She has observed more than 600 hearings since May 2020 and written more than 100 blog posts. She is on LinkedIn (here), and also on X (@KitzingerCelia) and Bluesky (@kitzingercelia.bsky.social)

[1] A Reference by the Attorney General of Northern Ireland of a devolution issue under paragraph 1(b) of Schedule 10 to the Northern Ireland Act 1998 UKSC/2025/0042

[2] Reconsidering Cheshire West in the Supreme Court: Is a gilded cage still a cage? by Daniel Clark

Cheshire West Revisited by Lucy Series

Reform, not rollback: Reflections from a social worker and former DOLS lead on the upcoming Supreme Court case about deprivation of liberty by Claire Webster

Place Your Bets: The Supreme Court vs The Spirit of Cheshire West by Tilly Baden

Cheshire West returns to the Supreme Court: The position of the parties by Daniel Clark

[3] For all blog posts published by the Open Justice Court of Protection Project on this topic (the list will be regularly updated up to and beyond the date when judgment is handed down),see: https://openjusticecourtofprotection.org/commentary-on-the-uk-supreme-court/

[4] For the avoidance of doubt (as lawyers like to say), I don’t include myself in this group. I know a lot about facilitating and developing open justice in the Court of Protection, but not very much about the daily processes whereby capacity assessments, best interests assessments and other decisions are made, or the way in which the Mental Capacity Act 2005 is implemented outside of the courtroom itself.

[5] https://www.gov.uk/government/consultations/open-justice-the-way-forward/call-for-evidence-document-open-justice-the-way-forward

[6] Neuberger §31 http://netk.net.au/judges/neuberger2.pdf

[7] Lady Hale https://www.nuffieldfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/speech-180514.pdf

[8] “Open Justice: Fit for Purpose” 4th June 2025, Green Templeton College Oxford. https://www.judiciary.uk/speech-by-mr-justice-nicklin-open-justice-fit-for-purpose/#:~:text=It%20is%20a%20means%20to,navigate%20the%20system.%5B5%5D

[9] Making harshly critical and offensive comments out of court about judges used to be a criminal offence in England and Wales, called ‘scandalising the judiciary’. It was abolished by Section 33 of the Crime and Courts Act 2013.

[10] Ambard v Attorney General of Trinidad and Tobago [1938] AC 322, quoted by the Lord Chief Justice (§12 “Open justice today”, Speech at the Commonwealth Judges and Magistrates Conference, Cardiff 10th September 2023 https://www.judiciary.uk/speech-by-the-lord-chief-justice-commonwealth-judges-and-magistrates-conference-2023/#:~:text=Secondly%2C%20openness%20requires%20those%20present,’)

[11] Under the Northern Ireland Act 1998, a “devolution issue” (including whether an Act of the government of Northern Ireland would be invalid as breaching the rights protected by the ECHR) may be referred to the Supreme Court for determination. The question referred to the Supreme Court on this occasion arises in the context of the provision of care and treatment for persons with cognitive impairments, and how their rights to liberty and security – under Article 5 of the ECHR are safeguarded. “The Attorney-General considers that the proposed revisions to the Deprivation of Liberty Safeguards Code of Practice (the ‘Code’) would adopt an approach to the scope of Article 5 which would differ from that outlined by the Supreme Court in the case of P v Cheshire West and Cheshire Council & Anor [2014] UKSC 191; [2014] AC 896, but which would nonetheless satisfy the requirements of Article 5. Accordingly, the Attorney-General seeks confirmation that the Minister of Health would have the power to issue the revised Code.” (from the very helpful leaflet about the case made available to people attending the Supreme Court in person).

[12] This is based on the argument (sometimes referred to as “the Ferreira Exception” although the case law therein referenced applied only to people in ICU and this is a significant extension of it) that “the true cause of their not being free to leave is their underlying illness”, not state detention. (R (Ferreira) v H M Senior Coroner of Inner South London & Ors (2017) EWCA Civ 3 (Court of Appeal) (Arden and McFarlane LJJ, Cranston J)

[13] The experienced observer and the novice(s) watch on their own laptops at home and communicate via WhatsApp in a separate confidential group set up specifically for that hearing and only open to observers once they confirm receipt of the transparency order (to ensure compliance with it).

[14] https://openjusticecourtofprotection.org/2025/10/21/a-summary-of-the-arguments-heard-by-the-supreme-court/

[16] We also ran a group discussion during the live-screening of a 2021 Supreme Court case and blogged about it here: Capacity to engage in sex: Nine responses to the Supreme Court Judgment in Re. JB by Daniel Clark, Dr EM, Marion Gray, Rosie Harding, Amber Pugh, Ruby Reed-Berendt, Kristy Regan, Kirsty Stuart, and an Anonymous Couple

[17] On the other hand, someone who was in the physical courtroom when I wasn’t there said that at least one of the judges had nodded off to sleep during the submissions. That wasn’t apparent from the recorded version, because the camera provides only a distant view (if any view at all) of those who are not speaking, and zooms in on whoever is making submissions and the judge responding to them.

[18] Neither the judges nor the barriers were wearing wigs (not required in the Supreme Court since 2007) but “wigs” remains a common synecdoche for judges (and barristers) as a potent symbol of their authority, much as does the gavel – something never used in English courts.

[19] Tilly Baden https://www.mysocialworknews.com/article/the-coffee-cup-made-headlines-but-the-fight-for-liberty-didn-t

[20] E.g. A court hearing and 23 visits from 16 officials: Family doubt that ‘Deprivation of liberty’ is working in the public interest

[21] Mark Neary’s objections to the use of “deprivation of liberty” was also cited by the AGNI. At 1hr 10 mins: AGNI refers his son as being “back home doing what he likes to do and king of his castle” and says that Mark “finds it very difficult to square that with the idea that he is “deprived of his liberty’.”

[22] This term is largely superseded these days by the umbrella term “prolonged disorder of consciousness” [PDOC] which would also have been the better diagnostic concept to invoke in this situation (since I suspect that the use of “persistent” was inspired by Airedale NHS Trust v Bland [1993] 1 All ER 821, a case in which the patient would now properly be referred to as in a PDOC). It’s a minor point, and judges can’t be expert on everything, but it grates nonetheless – because it’s not just language that’s at issue, but a body of knowledge which the judge, inadvertently, shows she doesn’t possess, and that knowledge has implications for the arguments being made. The structure of court hearings doesn’t permit of the opportunity for correction or education.

[23] Guzzardi v Italy 3 EHRR 333

[24] 1:38 AGNI .. the catastrophic dementia cases

[25] It’s on the recording at 24:26, 22nd October 2025 morning

[26] https://www.alzheimers.org.uk/sites/default/files/2018-09/Positive%20language%20guide_0.pdf

[27] https://openjusticecourtofprotection.org/2025/10/28/reflections-of-a-freelance-mental-capacity-consultant-on-the-supreme-court-case-about-deprivation-of-liberty/

[28] https://www.linkedin.com/feed/update/urn:li:activity:7389595516063342592/

[29] The Lord Advocate is Rt Hon Dorothy Bain KC and she was representing herself (with Ruth Crawford KC and Lesley Irvine) (starting at 1:40:50 on the recording of 20th October 2025, afternoon session, and continuing the next day, 21st October 2025, until 1:42:30).

[30] The Secretary of State for Health and Social Care was an intervener, represented by Joanne Clement KC (with Zoe Gannon). (starting at 1:42:40 on 21 October 2025 in the morning session and continuing in the afternoon until 1:01:32).

[31] Ambard v Attorney General of Trinidad and Tobago [1938] AC 322, quoted by the Lord Chief Justice (§12 “Open justice today”, Speech at the Commonwealth Judges and Magistrates Conference, Cardiff 10th September 2023 https://www.judiciary.uk/speech-by-the-lord-chief-justice-commonwealth-judges-and-magistrates-conference-2023/#:~:text=Secondly%2C%20openness%20requires%20those%20present,’)

[32] https://www.judiciary.uk/speech-by-the-lord-chief-justice-commonwealth-judges-and-magistrates-conference-2023/#:~:text=Secondly%2C%20openness%20requires%20those%20present,’

[33] https://supremecourt.uk/uploads/speech_lord_burrows_130925_5fd59648d9.pdf

I see the issues around Cheshire West. I see the issues around the MCA itself. I see the issues around deprivation of Liberty. I see the upcoming issues around Liberty Protection Safeguards.

Interesting that the government has launched a consultation now- only twenty years too late for many who have been caught up in this system!

The consultation may or may not provide a solution to all or even any of the issues that Ps and Families can be criminalised for talking about. Maybe the real solution is not about Cheshire West or Liberty Protection Safeguards – but the MCA itself as a whole? Maybe the real solution is quite simple – rip it up and start again! Though do so with the ability of experienced Ps and families to be major contributors in the whole process – if only the government will actually listen.

LikeLike

Wow! Along comes a UKSC case that, at heart, highlights the importance of your work – I’m delighted for you all 👏🏻❤️

Sent from my iPad

LikeLike

As much as you are ‘shocked and dismayed’ by these hearings, I am ‘shocked and dismayed’ by this blog.

Open Justice has not backfired. (Unless you mean that you have disappointed yourselves.) All that has happened is that a private WhatsApp Group of opinionated observers, many of whom may be stakeholders, has expressed a lack of confidence in a judicial process which is not yet complete, because they disapprove of some things which they have observed. This is not the breakdown of public confidence in the judicial system which Open Justice seeks to promote. The WhatsApp Group is not representative of the public, not democratic, and has no mandate to speak for the public, nor to tell the public what to think. Unlike the Supreme Court, no dissenting opinions are acknowledged. (You write that the verdict of the Group is mixed, but the comments quoted are one-sided.)

The purpose of Open Justice IMO is not to ensure that court hearings are Politically Correct. The purpose of Transparency of the judicial process is to foster public confidence that justice has been served in the final judgment. That is, all parties have been heard; the judges have acted fairly and impartially according to professional rules; and the final verdict is based on tested evidence and arguments, in accordance with established law, and not arbitrarily. Whether this purpose has been achieved cannot be determined before the final judgment is published.

The purpose of Court Observers, whether journalists or academics, is to be the eyes and ears of the public in hearings which are restricted. The role requires objectivity and impartiality. Observers are free to express personal qualified views and to criticise judges, collectively or individually, but not to purport to judge on behalf of all Observers, and certainly not on behalf of the public which they serve. Such criticism ought to be separate from the role of Observing.

This blog gives the impression that the purpose of Open Justice is to ensure that judges’ behaviour meets the expectations of any self-appointed group of Observers. That is not my understanding. Of course judges’ behaviour must not imperil the judicial process, such as berating or intimidating any party or witness, or otherwise interfering with their ability to present their case. However if some Observers take offence from the language judges use, even on behalf of those who are the subject of the court’s deliberations, this does not imperil justice being done.

Judges must be free to undertake their work as they see fit, and must be impervious to popular opinion. In our adversarial system the onus is on the parties to persuade the judges what is the correct understanding and interpretation of the law. It is not for the judges to restrict discussion according to their own understanding. Suppressing their own knowledge or feigning ignorance during a hearing is entirely appropriate. We are right to expect them to demonstrate erudition in the final decision, but not before. If the parties fail to raise and explore relevant positions, it is the duty of judges to do so, regardless of how unpopular those positions may be.

You appear to predict that the final decision will be a bad one on the basis of what you observed. However you appear to have no evidence on which to base such a prediction. Having observed over 600 hearings you have certainly had the opportunity to test to what extent the quality of hearings is a good predictor of the quality of the final judgment. But I am not aware if you have done so.

As you demonstrate, the Supreme Court is supremely transparent already. The Open Justice Project can provide little if any useful service here. Perhaps you have erred by trying to find an alternative purpose when your established purpose is redundant. I hope that the Project has no ulterior purpose of acting as self-appointed judges. That ought to be a separate function.

Barry Gale, writing as Mental Health Rights Scotland

LikeLike

I wasn’t able to observe the Supreme Court hearing but I’m intending to watch it when I have the time, and forming my own opinions about it. The blog post speaks to very important aspects of our judicial system, and addresses the process as well as the content of the SC case, and I wish I could have been involved that week in the observers’ WhatsApp group. Thank you for highlighting important issues.

LikeLike