By Celia Kitzinger, 4th January 2026

In a single month, December 2025. I observed five hearings involving nonagenarians – people in their nineties.

I didn’t seek them out. I couldn’t have done so, as there’s no way of discovering the age of protected parties from the public court lists (or their diagnoses). It just transpired that of the 13 hearings I picked to observe that month, five of them (more than a third!) concerned people aged between 90 and 97 – quite a remarkable proportion of my observed hearings given that this age group constitutes less than 1% of the population. All five had dementia diagnoses[1]: one in three people in their nineties has dementia according to the Alzheimer’s Society and this can obviously cause loss of capacity in relation to key decisions, making Court of Protection applications more likely.

I can’t imagine that anyone would choose to be involved – or to have their family members involved – in Court of Protection proceedings as they approach the end of their life. I’m not sure, though, having considered these five cases carefully (and looked at others we’ve blogged about) that there’s much we can do to avoid it.

I’ll first provide a description of each of the five hearings[2], and then (in the last section, “Reflections”) consider why these cases arise and what we can – and can’t – do to avoid becoming a protected party in the Court of Protection in our later years.

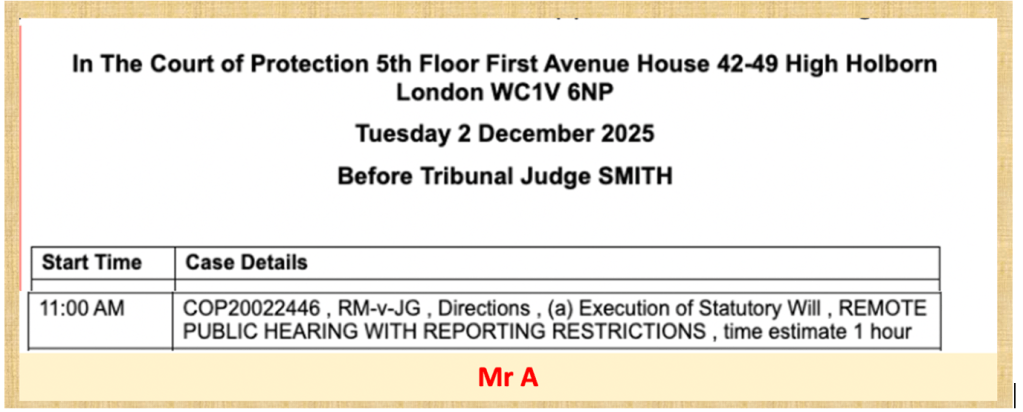

1. A statutory will for Mr A (97-years-old)

Deputy District Judge N Smith sitting at First Avenue House (London) on 2nd December 2025 (COP 20022446) – remote

Back in May 2011, Mr A, then in his early 80s, made a will (without benefit of legal advice) naming his wife of thirty years as his sole beneficiary. His wife died in February this year (2025), so he’s effectively intestate.

If he were able to make a new will, he would surely do so, but he’s now 97, has advanced dementia and is “very frail”. He was acutely unwell earlier this year and is now on an end-of-life pathway.

Medical records have been sent to counsel acting for Mr A via the Official Solicitor (Norman Lamb of Ten Old Square) and there is no dispute about either the fact that Mr A now lacks capacity to make a will himself, or about the urgency of the case, given that his death seems imminent.

The applicant in this case is Mr A’s step-daughter, who is in her early 60s now, so would have been around 19 or 20 at the time her mother married Mr A (who has no children of his own).

The step-daughter is applying for a statutory will (s.18(1)(i) Mental Capacity Act 2005), naming herself and her brother as joint beneficiaries of Mr A’s will and as executors of it[3].

If there were no statutory will and Mr A were to die effectively intestate, the beneficiaries would be his three nieces and his nephew (his late brother’s children). Step-children do not inherit anything under English intestacy rules[4]. The effect of the proposed statutory will, then, is to divert money that would otherwise be divided between Mr A’s three nieces and one nephew and give it instead to his two step-children.

The step-daughter says in her evidence to the court that she and her brother have a “longstanding close relationship” with their step-father, and that since her mother’s death she has “remained closely involved in [his] day-to-day life and welfare”. For example, he appointed her with Lasting Powers of Attorney for both Property and Affairs and for Health and Welfare, and she’s “dealt with his finances, arranged and monitored his care, and kept in regular contact with the care homes”. The Official Solicitor says that the evidence is that Mr A was indeed “close” to his stepchildren with relationships “of trust and mutual confidence” and “goes so far as to suggest [he] treated them as his own children”. By contrast, “there appears to have been limited contact between [Mr A] and his nieces and nephew” (Official Solicitor) – limited, says the step-daughter, to “birthday and Christmas cards”.

The nieces and nephew have all given their consent to the step-daughter’s application – one with a witness statement (on a COP 24 form) and the others in emails. Counsel for P by the Official Solicitor describes the emailed responses as granting “informal” consent and would prefer completed COP5s – especially as it was not clear what documents or information had been provided to the intestacy beneficiaries to base their consent upon.

Given the urgency of the case, though, the judge authorised the step-daughter to make the statutory will in the terms drafted and approved by the Official Solicitor – but ordered that she must serve a copy of the order and the draft will on the nephew and three nieces within three days. The order says that they can apply for a reconsideration if they have objections, but must do so within 23 days of the order being served.

The order also authorises the step-daughter to pay costs of the Official Solicitor (£8,000) from her step-father’s funds.

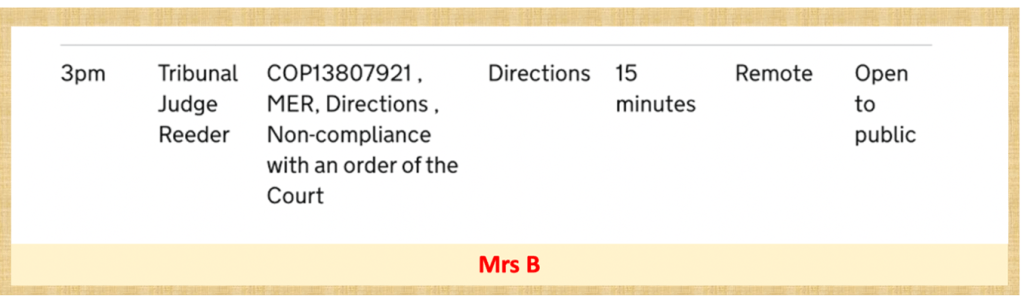

2. Daughter struggling as financial deputy for Mrs B (96-years-old)

Tribunal Judge Reeder sitting at First Avenue House (London) on 15th December 2025 (Case 13807921) – remote

This was listed as a “non-compliance” hearing, and I was expecting it to be about a public body that hadn’t obeyed court orders (see previous blog post). But when I joined the remote link the only person in court other than me and the judge was the daughter of a 96-year-old protected party.

After explaining the transparency order and checking that the daughter understood why I was there (and didn’t object), the judge asked her how her mum was.

Daughter: She’s good. She has dementia and she’s weak, frail, and a few times they’ve moved her to palliative care… She’s just in the bed now. She doesn’t always recognise her children… But she’s okay.

Judge: Are you all managing to see her?

Daughter: Yes. The way we do it is we’ve got like a rota system so one of us goes in every day.

The judge then explained (in a kindly manner) why the court had become involved.

Judge: In July 2022, you were appointed as Property and Affairs Deputy for your mother and asked for authority to sell her house and you didn’t get it. You then filed a standard authorisation… I’m not sure the court has ever dealt with permission to sell your mum’s house?

Daughter: I understood I would have to make another application.

Judge: The reason the court is bothered is a letter sent to the court from [your mother’s care home] saying that the fees had crept up and you owed them about £35,000. They say they’d tried to contact you and not managed. What caused concern is they said then they’d have to serve notice on your mother. The court is concerned to see what can be done so your mum doesn’t have to move out.

Daughter: Oh! The debt is now cleared and we’re now in whatever is the opposite of arrears. What happened was, the fees went up about a fourfold amount after Covid, so I was using her money to cover her fees. I asked my brothers to contribute some money in the form of rent – as they were living in her house. This never happened, so we got into debt. It’s all been very overwhelming for me as all contact was with me and I didn’t have the funds. But it’s sorted now. Reassessment took away most of the debt.

Judge: That was local authority’s contribution, was it?

Daughter: Yes. So, it took away most of the debt and we are now about a month in advance.

Judge: So, if I were to contact [the care home], they’d confirm that?

Daughter: Yes

Judge: You sure about that?

Daughter: Absolutely positive. I think they even had a little dance when it cleared!

The judge then asked for financial details – how much the mother’s contribution is, her income (“pension and some bits and bobs”) – and then turned back to the question of the house. It turned out that two of Mrs B’s sons – her brothers, in their 50s – are living there: “Well this is the struggle. For a good few years, they weren’t paying any rent – just obviously paying the household bills. Since the financial assessment, I’ve asked them to contribute some money, One brother is doing and one isn’t. He’s refusing to pay. He feels why is he having to pay rent on a house his parents have paid for. I can’t get him to see the enormity of where we’ve been to and that even though the debt is cleared now, we need to have a safety net for Mum”. She explained “I don’t want to speak bad of someone, but he just has lived there rent-free all of his life“.

After exploring some issues relating to the brothers and their situation, and how much rent each is paying, the hearing continued:

Judge: How can the court help? It seems to me there have been difficulties financially to ensure your mum’s care fees were paid. In January this year, [the care home] was so concerned they decided they might have to serve notice

Daughter: They did – they gave me 7 days.

Judge: They like your mum. They didn’t want to throw her out. So, they wrote to the court and asked how it could be sorted out. And you sorted it out. Has your mum made a will?

Daughter: Oh, that’s another reason I’ll probably be back in front of you. She didn’t.

Judge: So, there are two things I can do. One is, I can give you authority to sell the property. That will come with complications if the boys are living there, but that’s an order I can make today. The order could also record the importance of ensuring financial security going forward. Having heard from you, I’m satisfied the debt problem is sorted out and that you acted as deputy to sort the problem out as soon as possible. My concern is more about the future. The order could say to [your brothers] that the court expects them to pay a reasonable rent, as determined by you as deputy. Given where the house is, the rent you are asking for is a very reasonable amount of money. You can talk to a couple of estate agents about what rental it would fetch on the open market, and then – given your mum might want them to live there – give them a generous discount. And then you could go and see a local solicitor about the will. I can’t give you advice, but see a solicitor and get it sorted out!

The judge was kind and supportive to this litigant in person throughout the hearing and it was obvious he was trying to help her. I’m not sure she’ll follow up on the statutory will (I don’t think she understood what could be possible, or the urgency of doing it right away if the way the money would be distributed on intestacy isn’t what her mother would have wanted, or in her best interests). But she had clearly been worrying about the situation and was grateful to the judge.

The hearing ended with the judge asking “How old’s your mum? My maths is terrible!”.

Daughter: She’s 96. She always used to say she was waiting for a telegraph from the Queen –I don’t know that she understands it will be the King now – so maybe she’s hanging on for that. She’s so frail, but she’s still a fighter.

Judge: I can’t give her a telegram from the Royal family but I can give her an order from the court.

Daughter: That’s such a weight off my mind. Thank you.

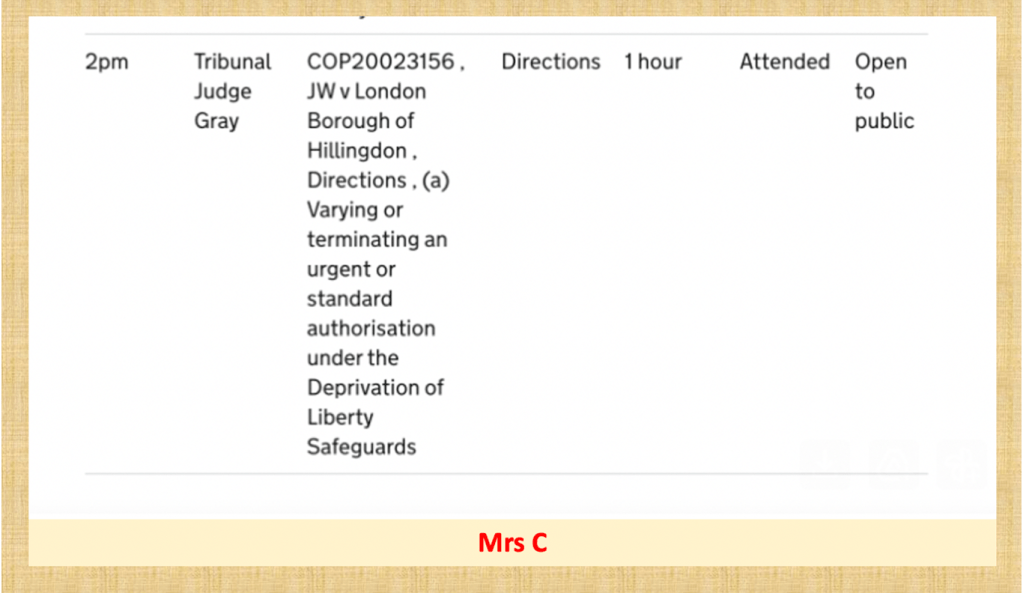

3. Deprivation of Liberty for Mrs C (97-years-old)

Tribunal Judge Gray sitting at First Avenue House (London) on 8th December 2025 (Case 20023156) – in person

Mrs C, aged 97 and already diagnosed with dementia, had a stroke in July 2025 and was admitted to (I assume) some kind of nursing home or care home. She must be indicating that she’s unhappy there, because this was a s.21A case, i.e. a review of whether or not her confinement in the current placement is a lawful deprivation of her liberty. The case has been brought on Mrs C’s behalf by her Accredited Legal Representative, Fernanda Stefani Araujo.

This was a very short hearing (about ten minutes, with an agreed order) so I didn’t learn much about Mrs C’s situation. She sounds very poorly, requiring “… round-the-clock care and oversight … due to her complex physical and mental health needs, which include cognitive impairment, reduced mobility, and a high level of dependency. Care staff fully support her with all aspects of daily living, including personal hygiene, dressing, oral care, skin integrity, eating and drinking, continence management, and mobility assistance. She is closely monitored to ensure her safety and comfort” (from the position statement for the local authority, London Borough of Hillingdon).

The local authority says that though they have a supervisory role in these proceedings, having granted the standard authorisation, the sole funding authority is NHS North West London ICB, who currently provide for Mrs C on an end-of-life care pathway, so they want the ICB to be joined as a party. The judge approved that. There is also supposed to be a social worker allocated to the case, and the judge asked for a statement about current care arrangements (from the ICB), and for information about whether P’s room has been “personalised”, about what’s happened about her belongings, and whether she has “access to the community”. I have asked for but not yet received the approved order (and the position statement from the ALR) which might help me better to understand what the issues are here that require the COP’s involvement, but (since Cheshire West) evidence of Mrs C’s objections to her current confinement more or less necessitate a s.21A application.

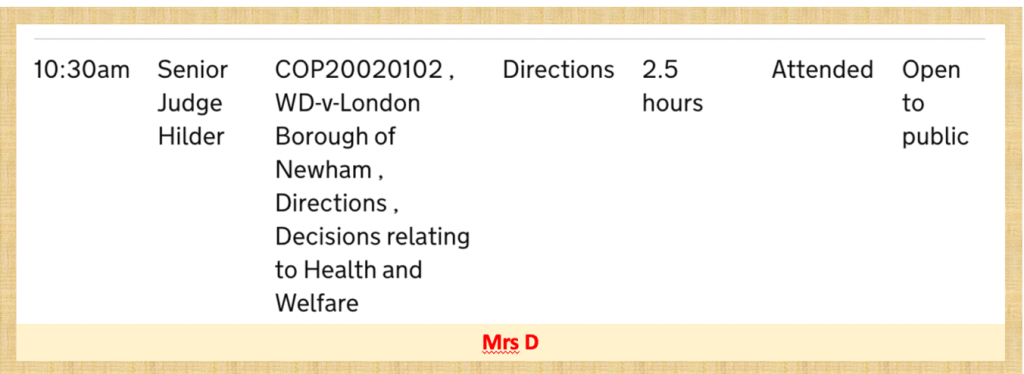

4. Contact arrangements for Mrs D (96-years-old`)

Senior Judge Hilder sitting at First Avenue House (London) on 5th December 2025 (Case 20020102) – in person

Mrs D, a widow aged 96, is living in her matrimonial home with one of her six (surviving) children, three of whom are parties to these proceedings, all as litigants in person. There are also eight or nine members of Mrs D’s family in court, including in-laws and grandchildren. It’s a crowded courtroom! Counsel for the local authority (London Borough of Newham) and counsel for Mrs D via her litigation friend the Official Solicitor are also in attendance[5].

In the background to these proceedings there is a financial dispute about who has interest in the property where Mrs D and one daughter are living. The case has been transferred (since August 2025) from the High Court where proceedings were started in relation to that dispute. Previous financial dealings relating to the property will be the subject of a report (due 24th February 2026) from Michael Culver, the interim panel deputy appointed in October 2025 after the Lasting Power of Attorney purportedly held by one of Mrs D’s daughters was disclaimed.

This hearing was almost exclusively about how Mrs D’s daughters and granddaughters could share out the time she has available between care appointments so that each of them would be able to see her regularly. It became apparent during the hearing that the members of this large family have disagreements not only about financial matters, but also about where Mrs D should live and receive care. Two daughters (M and S) each separately takes the position that Mum should live with her. M wasn’t in court, but S explained that “Access to my Mum has been very difficult. I have requested [of the sister who lives with Mum) to see her, and have been denied. If my mum can come and live with me, I’d see her as I want to. I love my mum. She’s my mum!” Senior Judge Hilder checked whether this might be different if there weren’t any difficulty with contact. “Then that would be fine. To be honest I think in her best interests, home is probably the best place. That’s where my mum’s heart is. She’s lived there a long time”.

The local authority believes it is in Mrs D’s best interests to remain living where she is. The Official Solicitor isn’t actively supporting a change of residence, but waiting for more evidence, including disclosure of care records, an up-to-date needs assessment, and witness statements from all the family members.

Senior Judge Hilder is very attentive to the needs of lay persons in her court – both as parties and more broadly as family members. She explained the meaning and purpose of the “third party disclosure order”: “Mrs D has her own legal representatives and they need to get to know her. One way is to get some records from the carers. So, they will write and say, ‘Dear care agency, please can you give to Mrs D’s own solicitors a copy of all the records from 1st June’ – only to her own solicitors. If they are relevant to the decisions that need to be made, then the Official Solicitor will disclose onwards, but otherwise these records won’t be disclosed to anyone else. That’s to stop us all from drowning in paperwork and it preserves Mrs D’s privacy.”

The judge also went carefully through the schedule and deadlines between now and the next hearing.

- 30th January 2026 for the needs assessment;

- 13th February 2026 for the family evidence (“By 4pm. Use the COP 24 form which has a statement of truth at the end – google and you’ll find it. Say what you think about the needs assessment, then where you think Mrs D should live, and then what you think she needs for her care.” And turning to counsel for the local authority, “So that all this is as clear as possible for the family, please spell it out in the order”.)

- 27th February 2026 for a response from the local authority

- 6th March 2026 for a ‘wishes and feelings’ statement to be obtained by Mrs D’s legal representatives

- Week beginning 9th March 2026 for a Round Table Meeting (“So, to be clear for the family members, after all this evidence has come in, it’s time for everyone to get together and see if they can agree what’s in Mrs D’s best interests. It used to be done as a conversation sitting around a table, which is why it’s called that….”) Following discussion of dates and times and everyone’s availability it was agreed for Thursday 12th March 2026 (9.30-11.30am). “The LA will send everyone an Agenda by 4pm on 6th March and will arrange for a minute taker and circulate minutes within 7 days of the meeting. The idea of the meeting is that you all know what everyone else is saying, and you use this to try and reach agreement if you can. And if you can’t, then you work out the scope of the disagreement.”

- 24th March 2026 – deadline for the LA position statement (“I don’t require unrepresented parties to file position statements”)

- 10am 1st April 2026 Next hearing, in person at First Avenue House.

Finally, Senior Judge Hilder spent a lot of time sorting out arrangements for contact between each family member and Mrs D over the four-month period until the next hearing. I’m full of admiration for the painstaking and meticulous attention she paid to this, but also rather dismayed that it falls to a senior judge in the Court of Protection (with a salary of £173,854) to have to establish how the details of everyone’s school run, childcare arrangements and work commitments fit around their wish to see Mrs D, at her house, at their home, or at the home of another family member; how much notice Mrs D and the daughter she lives with would need to be given of an impending visit (48 hours); and what they’d do if she got too tired to engage, or wanted to go home early. And these family visits have to be fitted around the carer who arrives every day sometime between 9.30am and 10.15am, and the nurse who gives the insulin injection between 10am and 12 noon each day, the evening care at 4pm and church on Sunday. She checked how Mrs D would be transported from her home to other family members’ houses (not all of them have cars), whether she would be given something to eat while there, and how family members would communicate effectively while Mrs D was away from home (“Do you use WhatsApp? Because that’s quicker than email and you can get it to ping so you know a message has arrived?” (Judge)).

A large family all wanting to spend time with Mrs D is, as the judge said, “a lovely problem to have!”. As to whether it really needed to be decided by a judge – one would hope not, of course, but I have seen too many other cases where arrangements were agreed in loose terms with unparticularised details, or left to the discretion of the parties and by the time of the next hearing everything had fallen apart and discord between the parties was exacerbated as a result.

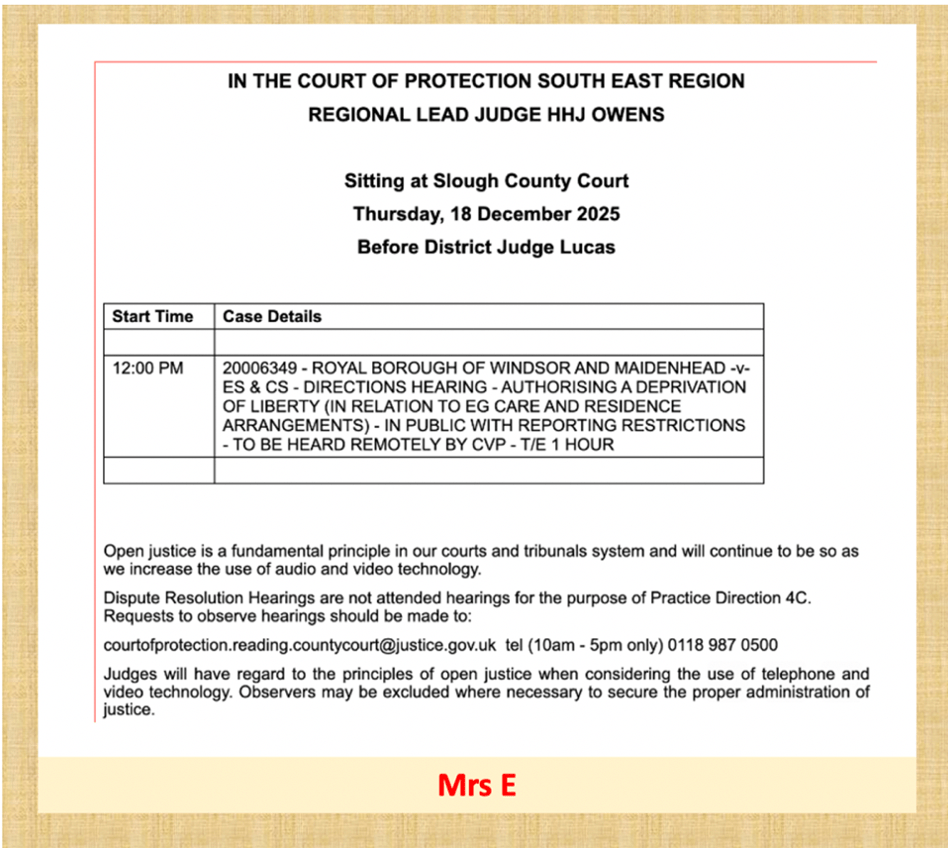

5. “A warzone”: Safeguarding, care and residence for Mrs E (90-years-old)

District Judge Lucas sitting in Slough County Court (London) on 18th December 2025 (Case 20006349) – remote

From what I’ve seen of it[6], this case is a disaster and I feel desperately sorry for the family at the centre of it.

“I don’t want to be accused of hyperbole,” said DJ Lucas, the Judge who has heard the case from the outset, “but we are in the middle of a war zone, and at the centre is a lady with dementia who has difficulties…” (July 2025 hearing). The more senior judge who was assigned the case for an urgent hearing in November 20025 (HHJ Greenfield) unknowingly used a similar military metaphor when he expressed concern about the parties “setting down battle lines”.

The matter has been before the Court for more than a year (since November 2024), with about seven hearings so far, and no date yet for a final hearing. It was back before DJ Lucas in December 2025, a month earlier than he’d anticipated (there’s a ‘case management’ hearing in January), because HHJ Greenfield was persuaded to order an earlier hearing after the urgent hearing before him, consequent upon the protected party having lost her litigation friend, due to lack of security for costs.

But in fact, nothing had changed. DJ Lucas opened the December 2025 hearing by saying: “I have real concerns about the progress of this litigation. I’m struggling to understand why we are back again…. There is a bundle of 1,800 pages… There is vast non-compliance with the last order. I dread to think how much money has been spent and we’re no further forward than last time – and it seems P’s finances have been completely exhausted by this litigation. I was assured there was an ongoing review of care, but it seems that hasn’t happened…”.

Mrs E is 90 years old, and has a diagnosis of Alzheimer’s with psychotic features. She lives at home with her daughter, and there is a barrage of allegations against the daughter ranging from threatening to kill her mother to being rude to carers. Safeguarding concerns are reported at every hearing. Initially, the local authority (Royal Borough of Windsor and Maidenhead) sought to ban the daughter from entering her mother’s home and from “interfering” with her care – but it transpired that the daughter owns the house (jointly with her mother and her sister), and she’s currently living there. So then they made an application that it’s in Mrs E’s best interests to live in a care home. The local authority has also applied for revocation of the Lasting Powers of Attorney for Health and Welfare held by the daughter (it’s “suspended” at present), on the grounds that she has failed to act in her mother’s best interests. The daughter opposes both those applications and has made her own application to be appointed (with her sister) as Deputy for her mother’s property and affairs (which is opposed by the local authority)[7].

Earlier in the proceedings, a fact-finding hearing was proposed, but by the July 2025 hearing that was in doubt since the “brief and unparticularised schedule of allegations” served by the local authority was “not in a form which facilitates the identification and/or resolution of disputes of fact between the parties and/or by the court” (order from July hearing). At the August 2025 hearing it was decided that a fact-finding hearing was disproportionate: instead, an independent social worker (ISW) was to be instructed to consider the risks to Mrs E of living at home with her daughter and where her best interests lie in respect of care and residence. At the December 2025 hearing, it was reported that the ISW had been instructed, but this had gone ahead without the parties having been able to reach agreement about either the letter of instruction or which parts of the bundle should be sent to the ISW. (The judge ordered that the full bundle should go to the ISW.)

In the meantime, and despite the danger the daughter is said to pose to her mother, there are no contact restrictions in place: they live together and sleep in the same room – not by choice, but because the cottage is small and has only two bedrooms. The local authority insists on a care package involving 24/7 care, and the night-time carers sleep in the daughter’s bedroom, so she’s moved in with her mother. The daughter says no night-time care is provided: the carers simply sleep on the premises. A recital at the previous hearing noted that the local authority had agreed to “provide an update regarding night-time care provision for P prior to the next listed hearing” but they haven’t done this. There’s also a dispute about use of the “Garden Room” (modern bedsit accommodation in a purpose-built construction installed in the back garden) which is currently unused. The carers won’t sleep there for fear of its distance from Mrs E’s bedroom compromising whatever (disputed) contribution they make to her night-time care. The daughter won’t sleep there for fear that her mother will risk her safety by coming to look for her, down steps and through the garden, in the dark.

Carers also accompany mother and daughter whenever they leave the house – not, says the local authority, to supervise contact (which the court hasn’t authorised them to do) but to provide support for Mrs E in accordance with the care package. The daughter says this isn’t needed and intrudes into their private and family life. The local authority has not completed the care and support plan scheduled for 1 November 2025 and now say they are unlikely to do so. A draft Working Together Agreement has been contentious and is not agreed.

There are also concerns and apparent disagreements about Mrs E’s mental health conditions – the level of Aripiprazole she’s receiving, her episodes of “agitation” and what triggers them, and whether in fact it is really necessary for the community mental health nursing team to visit her on alternate days (which her daughter worries may in fact contribute to Mrs E’s agitation). The judge authorised a s.49 report from the Trust covering these matters, but it won’t be available until after the date of the next listed hearing.

Finally, Mrs E remains a party but hasn’t had a litigation friend for the last two hearings. At the urgent November 2025 hearing before HHJ Greenfield, the Official Solicitor (OS) was discharged because there was no security for her costs. This was a source of contention between the LA and the OS. The local authority criticised the solicitor acting for the OS, complaining of “extremely high costs” and threatening a “wasted costs order” against the OS. Counsel for the OS described this as “a highly unusual and problematic position … from the local authority” pointing out that “it is the local authority’s delays that bring us back to court, once again”. The matter will be referred to the Senior Courts Costs Office. Following this exchange, counsel for the OS left the hearing.

By the time of the December 2025 hearing, the local authority said they would pay for an Accredited Legal Representative (ALR) to represent Mrs E, but only on condition that a charge is put on Mrs E’s share of the property she owns with her daughters, so that the LA can recoup the cost from her estate “when she is no longer with us”. This led to a discussion about a cheaper option – use of an advocate – but the judge ruled in favour of an ALR, to be formally appointed at the next hearing.

The next hearing, on 29th January 2026 was originally supposed to deal with case management towards a fact-finding hearing. The hearing is still planned to go ahead, but obviously not to that purpose: I’m not clear whether or not the ISW report will be available by then (the s. 49 report will not be), or what the issues will be for the court to address.

As a member of the public observing this case, I am appalled at what looks to me like a flagrant waste of public money, which seems only to have caused harm to this family for over a year. The burdens imposed on Mrs E and (especially) her daughter by the ongoing and inconclusive hostilities in this litigation “war zone” must be immense. This cannot be right.

Reflections

Personally, I really don’t want a case to be brought to the Court of Protection about me, or anybody I care about, in my old age. It’s stressful for everyone, time-consuming (at a life-stage when there’s not much time left), and expensive. I’d rather spend my last months or years doing whatever I can still enjoy with the people I love – not being assessed for my decision-making capacity and interrogated about my wishes and feelings, so that my ‘best interests’ can be constructed on terms imposed by the administrative forms and formulae of the “person-centred” court bundle.

There are obviously some things we can do to make it less likely that we’ll be subject to the Court of Protection in our later years – including making robust wills, and creating lasting powers of attorney[8]. We can also plan ahead for care home fees, or for live-in home care, and discuss with family in advance how we expect that to be managed, and put key expectations in writing. Both Mr A’s stepdaughter and Mrs B’s daughter could perhaps have avoided court with these measures in place. But planning ahead will only take us so far.

If we survive for a decade or more after losing testamentary capacity, it’s quite likely that any will we’ve already made won’t fit our changed personal and financial circumstances in the way we might have hoped (hence the applications for statutory wills[9].) I think there are ways of creating more ‘flexible’ wills (e.g. with discretionary Trusts and a Letter of Wishes) but that’s also more complicated and more expensive – though I don’t know if it would cost more than the £8,000 Mr A’s stepdaughter had to pay the Official Solicitor to sort out his statutory will.

Although I’ve used Lasting Powers of Attorney to appoint family members to act for me, both in relation to Health and in relation to Finance and Property, I regularly see hearings where decisions made by people holding LPAs are overruled by the court, and they are placed in positions where they feel the only answer is to “disclaim” their LPA, or have it removed from them (Mrs D’s and Mrs E’s daughters). Of course, there can be good reasons for involving the court when LPAs are not validly made or when attorneys are abusive – but public bodies also initiate court hearings simply because they disagree with a decision made by an attorney. Although I hope that my attorneys can be my decision-makers in future if necessary, the reality is that they may simply be targeted for making the “wrong” decisions and we’ll all end up in court. And there are some decisions that attorneys can’t make anyway[10] – a statutory will is one, and “deprivation of liberty” is another. Both require court applications.

Following Cheshire West, if you’re living in a care home (or in any other way confined in a manner imputable to the state), and you’re thought to be objecting, then there is very likely to be a Court of Protection case about you – as there was for Mrs C. A court case might be a good thing if you’re deprived of your liberty unwillingly – as in the case of the “defenceless 91-year-old gentleman” who was “removed from his home of 50 years and detained in a locked dementia unit against his wishes” for well over a year. The court hearing resulted in his return home with a proper package of care, and £60,000 damages for his unlawful detention (Essex County Council v RF & Ors [2015] EWCOP 1). A court case might mean you at least get a “trial” of living at home – as did 89-year-old Manuela Sykes (with dementia) who was discharged from two months in hospital not back into her own home as she wished, but into a nursing home, where she was desperately unhappy. This was in spite of the fact that she’d had the foresight to appoint an LPA (instructing him that “My wish is to remain in my own property for as long as this is feasible”) and she’d made a “living will” (refusing life sustaining treatment). A year later, a judge ruled in favour of a trial at home it didn’t work out (she was aggressive towards carers), and after three weeks she was back in the care home, and died there three years later[11].

In my experience, s21A cases rarely result in a return home (or not for long). One woman in her 90s died in hospital waiting for a court decision (“Why can’t a 91-year old return home to her son?”); another was home for just 20 days after being diagnosed with a terminal illness “’Bureaucracy blots out the sun’: Telling Ella Lung’s story”. The protected party’s home is often said to be unsuitable, even ‘uninhabitable’, due to hoarding, clutter, lack of hygiene, disrepair, or simply its inaccessibility for the disabled person who can’t get up the stairs without a stairlift, or is at risk of falls without grab rails. It’s common for there to be lengthy delays while repairs and adaptations are sought. Family members (usually spouses or adult children) are often described in negative terms: in one s.21A case, the daughter of an hundred-year-old woman was said to be “coercive and controlling” and she didn’t “cooperate” with the social worker who wanted access to the house (“Centenarian challenges deprivation of liberty…”). Even people holding Lasting Powers of Attorney are often side-lined in s.21A cases, and treated (unfairly) as having suspect motives (see: “Our ordinary story…” for another nonagenarian example)[12]. Neither the public bodies, nor the court, seem able to make decisions with the speed required for timely and effective action on behalf of people over ninety – and in any case, there are often no realistic alternatives to institutional care (e.g. “home” has been sold, or the local authority refuses to provide a home care package). It’s not unusual for the protected party herself to refuse care: many elderly people find home care intrusive and upsetting, and are convinced (in the face of evidence to the contrary) that they don’t need it – like Manuela Sykes, or “Hattie” the 96-year-old I wrote about in “Resisting care….”). In many cases, the only concrete outcome of the s.21A application is to cause distress P and their family (“A court hearing and 23 visits from 16 officials”; “Final considerations for a s.21A challenge: Questions about truth-telling to someone with dementia…”; “‘What God has put together, let no man put asunder’: A s.21A challenge and the limits of Power of Attorney”).

If your relatives all argue about what’s best for you – including arguments about who gets to spend time with you and when – then that, too, can end up before a judge, as in the case of Mrs D. In another case we’ve blogged (“Eight litigants in person”), the applicant and her seven siblings were all parties in a case concerning their mother, aged 96 (with dementia) who lived at home with the applicant daughter. Arguments covered the use of the mother’s funds for building work to enlarge the mother’s bathroom and accommodate a paid carer, and the purchase of a car and contact issues. It seems unlikely that there’s anything much we can do to ensure that our relatives don’t disagree with each other about what we need, how we should be cared for, or who should visit under what circumstances (though an advance “letter of wishes” might help).

I recognise (with regret) that caring for me in my old age might well drive my nearest and dearest to entertain feelings of “suicide and homicide” (as Mrs E’s daughter unfortunately informed a professional) – especially in the context of failing health and social services, and the challenges of obtaining appropriate care. I don’t want this to trigger a full-scale “safeguarding” investigation or proposals for “fact-finding” hearings as happened with Mrs E – not even if someone raises the possibility of a trip to Dignitas (the Swiss assisted dying clinic), as a daughter did in another case concerning safeguarding for her elderly mother, leading to orders with a penal notice (“Safeguarding Mum: The ‘vile judgment’ and the daughter’s story”). I certainly don’t want court orders with penal notices against my wife or my sister (my two attorneys) in the event that the court tries to limit or restrain their behaviour.

But all of this is out of my hands. Like many others, I would like to believe that the people I trust, who I’ve appointed as my attorneys, would fulfil the trust I’ve placed in them and would be able to make decisions for me if I cannot. But some decisions are excluded, and others can be contested by professionals acting in my “best interests” (however they conceptualise those at the time). I can’t rule out becoming, in 20 years time, a non-capacitous and fiercely independent older person like “Hattie” who resists the home care package others believe I need. I can’t rule out becoming a victim of coercive or controlling behaviour, predatory marriage, cuckooing, or abuse (as many other vulnerable elderly people have done) – and I can’t rule out medical non-compliance with my Advance Decision to Refuse Treatment, in which event I actively want my attorneys to make an application to Court of Protection to compel them to comply and to seek damages against them. So I recognise that a COP hearing may be necessary for me in future – and even if (in my view) it isn’t, there’s nothing I can do to stop someone from making an application to the Court of Protection about me, and nothing I can do to stop a judge from deciding to hear it.

Celia Kitzinger is co-director of the Open Justice Court of Protection Project. She has observed more than 600 hearings since May 2020 and written more than 100 blog posts. She is on LinkedIn (here), and also on X (@KitzingerCelia) and Bluesky (@kitzingercelia.bsky.social)

Footnotes

[1] I think this is correct but it’s possible that I’ve misremembered in the case of Mrs D, the only person for whom I’ve not recorded a dementia diagnosis in my contemporaneous notes, but I think I recall it being mentioned in court. I do not have any court documentation for Mrs D so am not able to check this.

[2] Material purporting to be direct quotation from what was said in court is based on contemporaneous touch-typed notes and is as accurate as I can make it, but unlikely to be verbatim.

[3] The OS had already made some suggestions for changes which she’d accepted – including provision for who should inherit in the – (as she said) unlikely! – event that she and her brother were to die before Mr A.

[4] https://www.citizensadvice.org.uk/family/death-and-wills/who-can-inherit-if-there-is-no-will-the-rules-of-intestacy/

[5] My account of this case is based solely on what was said during the hearing. I requested Position Statements of all parties via the judge, who approved disclosure from both the Official Solicitor and from the local authority – but as neither party had prepared anonymised versions (in compliance with Poole J’s guidance), directed that they should be sent to me after the hearing. I have never received them. The lay parties had produced documents headed (at least in two cases “Position Statements”) but the judge had not directed Position Statements from the lay parties and did not approve disclosure. If there are errors in my account of this case, this is due to my reliance of my notes from the hearing, not having received any documentation.

[6] I was alerted to this hearing by Claire Martin who has observed two previous hearings (and shared her notes with me) and asked me to observe this one because she was concerned about how Mrs E’s daughter is being represented to the court, and the likely consequences for her and for her mother of the way these proceedings are conducted. Having watched the December hearing, I share those concerns.

[7] The judge decided, at the December hearing, to split the proceedings, so that the Deputyship application is dealt with separately.

[8] Failing to appoint anyone with power of attorney means that if a family member or friend wants to manage your affairs, they have to make a court application for deputyship (as Mrs B’s daughter must have done), or that you end up paying for a professional deputy, It also risks fights between your nearest and dearest about who should act as deputy for you (e.g. a close friend and a family member both applied to be deputy – and refused to do it jointly – in this case of a 98-year-old with dementia, Re AW: [2015] EWCOP 16; a family member applied to be deputy in place of a professional deputy appointed by the local authority for a 95-year-old with dementia: Re JW [2015] EWCOP 82).

[9] My sister, Polly Kitzinger, made a mirror will with her partner when they bought their first house together in 2004, making each of them the other’s primary beneficiary. Five years later, she suffered devastating brain injuries in a car crash. Eighteen years on, that will was clearly not what she would have wanted, given her changed circumstances, with the house long ago sold and her partner married to someone else and no longer visiting her (see “Applying for a statutory will”).

[10] Other decisions that the person appointed as Lasting Power of Attorney cannot make include consenting to a marriage or civil partnership, or to sex (neither can the court); consenting to a divorce (from a marriage) or dissolution (of a civil partnership) – but the court can do this; and consenting to a child being put up for adoption or to treatment under the Human Fertility and Embryology Act 1990 – again the court can do this.

[11] Manuela Sykes was one of the first “P”s in Court of Protection proceedings to be publicly named, and she sounds an amazing woman. Check out her obituary and the recollections of her by Romana Canneti, a lawyer who was interested in the case from a ‘transparency’ perspective. The judgment, by DJ Eldergill, is Westminster City Council v Manuela Sykes [2014] EWHC B9 (COP).

[12] For a lovely example of a friend acting as Lasting Power of Attorney for a woman in her early 90s, whose advocacy was taken very seriously by the judge, and led to a successful ‘trial at home’ for almost two years, take a look at these blog posts which chart the unfolding of a single case over time: A section 21A hearing (3rd May 2022 hearing); “What good is it making someone safer if it merely makes them miserable?” (30th May 2022 hearing); “Trial of living at home: Successful so far” (7th July 2022 hearing); “The story of TW and her amazing friend and attorney – two years on” (11th March 2024 hearing)

This makes me grateful for the fact that I have only one relative likely to take the remotest interest in my affairs! But, having said that, I realize I am discounting my two small grandsons who will be grown up if I live to be 100. As you say, in the end you cannot control the end, however much that goes against the habits of a lifetime.

LikeLike