By Daniel Clark, 23rd January 2026

On Thursday 15th January 2026, I observed a hearing before District Judge Davies who was sitting remotely (via Cloud Video Platform) at Chesterfield Civil Justice Centre.

At the start of the hearing, the judge criticised me for the way in which I had acquired the link to the hearing. Whether he intended it or not, I experienced this as belittling.

After the hearing, I came to realise quite quickly that I’m not the only observer who has felt unfairly criticised by a judge. In comparison to some other accounts, my experience was what I’d categorise as being at the lower end of seriousness. But it’s quite clear that there’s a common theme of judges criticising observers for things that only happen because the process of sending links and admitting observers (the responsibility of HMCTS) hasn’t worked as it should.

Of course, observers are not above criticism. For example, I’ve seen one judge (Mr Justice Hayden) tell an observer who (accidentally) turned on their camera and microphone, while having a conversation with someone in the room with them during the hearing, that this was unacceptable and he would have them removed if it persisted.

That’s an example of fair judicial criticism.

But this blog isn’t about fair judicial criticism. It’s about unfair judicial criticism, and how it harms the judicial aspiration for transparency.

First I’ll explain exactly what happened on 15th January 2026, and then I’ll describe other people’s experiences of judicial criticism, and explain why this is bad for transparency.

Transparency matters: Judicial criticism of an observer

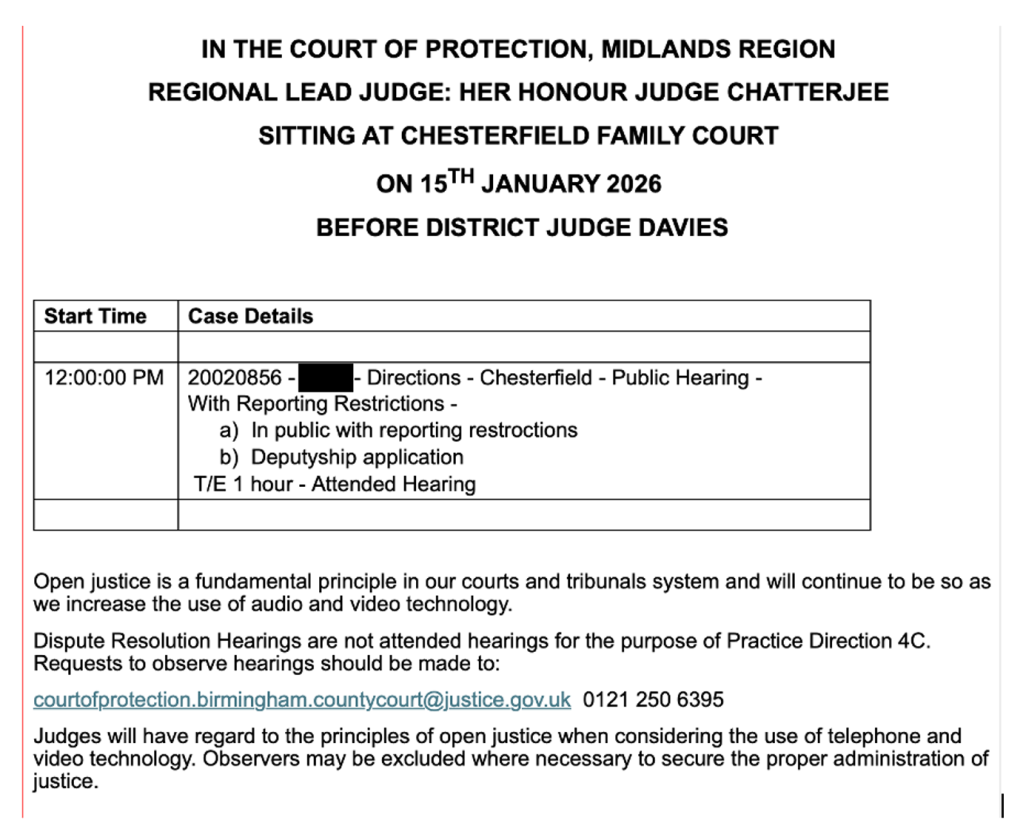

This case caught my eye because it was listed as being heard in person at Chesterfield Family Court. (See the listing from Courtel/CourtServe below: note all screenshots were taken after the hearing had concluded).

The listing is in error – there is no Family Court building in Chesterfield. But I know Court of Protection hearings can be heard at Chesterfield Justice Centre, which is within reasonable travelling distance from my home. As I recently submitted my PhD thesis, I have some time on my hands to watch hearings, and to make things even easier, the listing was posted to CourtServe around midday the day before. That meant I had plenty of time to plan my travel.

At 08:39 on the morning of the hearing, I sent an email to the hearing centre itself to enquire as to whether the hearing was definitely going ahead. I didn’t want to travel all the way to the court only to find out that it had been vacated! I did consider calling but felt like there’d be no chance I’d get through at 9am. Better to send an email, hope it’s noticed, and then call at 9:30 if I don’t get a response.

Court of Protection hearings are supposed to appear in a Court of Protection list on Courtel/CourtServe (and usually do), and we are asked to send requests to observe to the regional Court of Protection “hubs” – in this case, as indicated in the screenshot above, the Birmingham hub.

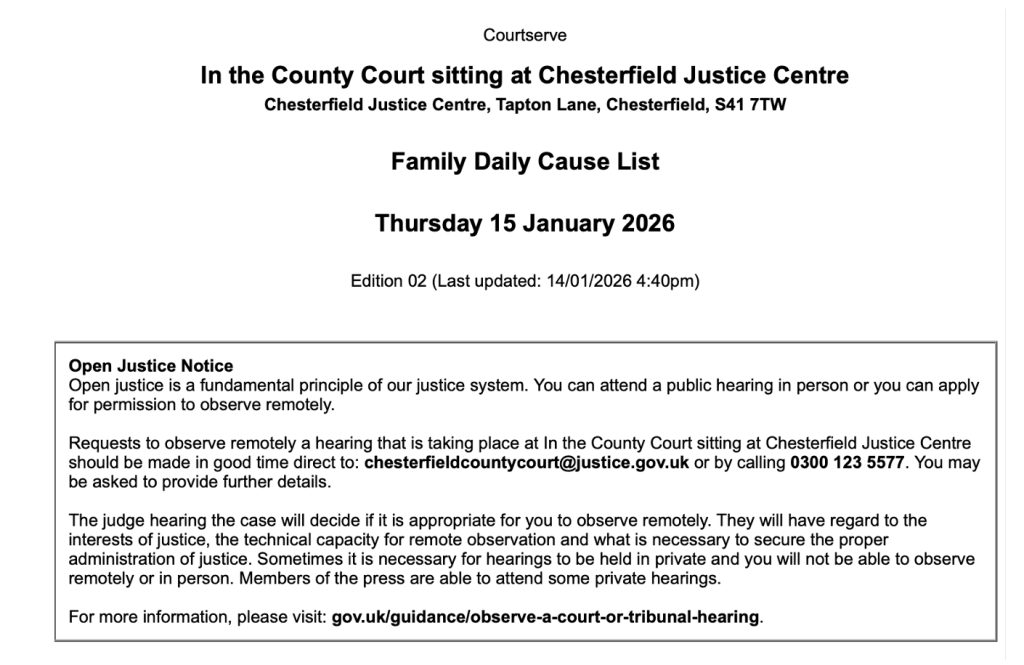

But I wasn’t making a request to observe; I was making a request for information. The Chesterfield daily cause list (in a different section of Courtel/Courtserve) gives the email address for the hearing centre itself.

As you can see, the “Open Justice Notice” tells you to contact Chesterfield Justice Centre directly if you want to observe a case that is being heard there. And even if it wasn’t in the CourtServe list, the court’s official webpage also includes its contact information. So, I thought, there’s really no harm in using that email address to enquire if an in-person hearing is definitely going ahead. Besides (I thought) the Birmingham hub would probably just forward my email to Chesterfield anyway.

I received an email response at 09:10 that said “the Court can confirm that this matter remains listed as a remote hearing”. Though I didn’t immediately notice, this response was actually sent by an Administration Officer at Derby Court. Somebody in Chesterfield must have forwarded my email to them.

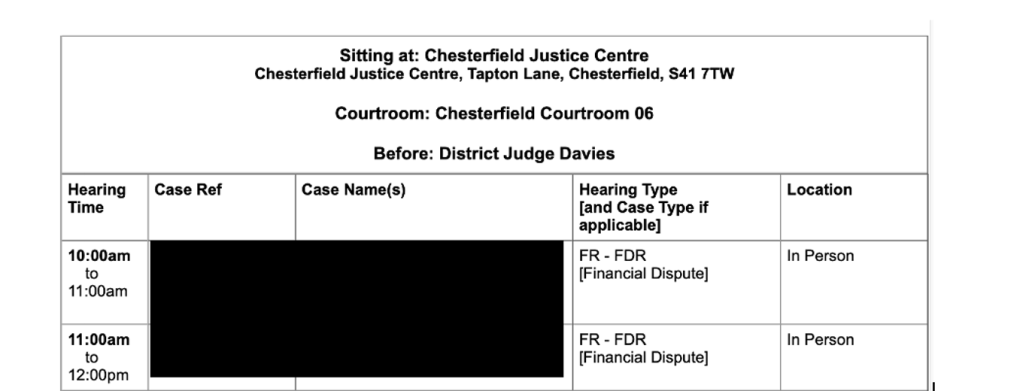

The fact the case was to be heard remotely was news to me. Confused, I double-checked both the Court of Protection list and the daily cause list. The case wasn’t even in the daily cause list as you can see below. I’ve removed the case name because they included people’s surnames. While I imagine that’s perfectly fine, I don’t actually know. And the parties probably never imagined their names would be broadcast in a blog like this – and certainly not in a publication that has nothing to do with them.

I therefore did what I thought was reasonable and, at 09:16, responded to the email (from the Derby court) asking for the link, Transparency Order, and position statements. I also said, “I appreciate this is an unusual way of requesting this so, if necessary, I am of course happy to direct this request via the Birmingham hub.”

At 09:30, the member of court staff asked me to “contact Birmingham direct”, who were copied into the email. After I didn’t get a response, I sent a follow-up to the Birmingham hub at 10:28.

My request to observe was “approved” at 10:56. At 11:10 somebody from Derby Court (but a different person in a different team to the one who directed me to Birmingham) sent me the Transparency Order, and said “the Judge would also like me to let you know both parties are litigants in person so it is unlikely there will be position statements” (my emphasis).

At this point, I thought perhaps the case had been re-listed, as remote, under Derby. I checked Derby’s daily cause list. Neither the case nor the judge featured.

At 11:54 I received another email from the same administrative officer. That email said “the Judge has asked me to inform you that the local authority will also be joining the hearing asking to be joined as parties but they too will not be filing a position statement” (my emphasis).

Before getting into with what happened at the hearing, I think it’s useful to set out what had happened so far.

- I sent an email to the Chesterfield court asking whether the hearing was still going ahead.

- At some point, somebody in Chesterfield sent my email to a team in Derby.

- I received a response from Derby telling me the hearing was remote. When I asked for the link, I was directed to the Birmingham hub.

- After I contacted the Birmingham hub, a member of staff in the hub told me my request to observe had been approved.

- At some point, somebody in the Birmingham hub sent my contact details to a different team in Derby.

- Somebody from Derby sent me the link and Transparency Order, and a couple of messages from the judge.

Court staff are hard working and over-stretched. But I cannot help but think that this is a deeply inefficient way of working – particularly because, as it turned out, the judge knew about my request to observe before I contacted the Birmingham hub.

When the judge (who was sitting at Chesterfield in a hearing administered by staff at Derby) joined the link at 12:03, he acknowledged my presence, as this same judge (who I have observed often before) has done previously. Somewhat unusually, he asked me to turn on my camera. He confirmed nobody objected to my presence (they didn’t). And then he addressed my request to observe.

The judge said that he’d had to tell court staff to “re-direct” my request to observe via the Birmingham hub because there needed to be a paper trail and that I should direct requests to observe to the hub, not the local courts, because there aren’t enough administrative staff to deal with requests to observe.

It seemed reasonable enough to convey this information to me. But the way in which it was done concerns me.

The judge had already asked the administrative officer to tell me two pieces of information in two separate emails (first that the parties were litigants in person and then that the local authority had asked to join the hearing). He could have asked them to give me this message, too, via email. But he didn’t. Instead, he chose to wait for the hearing where he could air his grievances in open court – grievances that could not reasonably be said to have had any effect on the administration of justice, and were completely irrelevant to the issues before the court.

I have an unfortunate habit of blushing when I’m irritated. I imagine I was blushing when the judge was speaking. Did he really need to hold-up the hearing to address me on how I’d requested the link? I assume he’d seen my emails (they’re usually forwarded to judges) and so must have seen that it was me who suggested I contact the hub if required. He therefore must also must have seen that my original email was premised on the idea that the case was to be heard in person.

Whether the judge intended it to be or not, this felt belittling – like I’d been caught with my hands in the cookie jar, and a teacher was giving me a reprimand (albeit a relatively gentle one) in front of the class. Perhaps the judge didn’t intend it to be belittling; perhaps he thought it was helpful. Indeed, that’s why Claire Martin thinks that HHJ Thomas had “suggested” she send requests for links “earlier” – something that, as Claire explains, is not achievable in practice due to the fact that case listings are usually published late the day before.

But the situation faced by Claire, and the one faced by me, is different for one key reason. DJ Davies had already used an administrative officer to convey information to me. If he wanted to be helpful, why not just use those open lines of email communication?

Of course I didn’t say any of this. But, whether the judge was looking for a response or not, I was determined to say something. So I turned on my microphone and told the judge that the only reason I’d contacted the hearing centre was because the case was listed as in person, and I wanted to check it was still going ahead.

Not quite the zingy response I’d have liked but I liked the feeling of having to defend myself even less. As I saw it, the judge had criticised me in open court. I had a right to respond but had to do so on the spot. This blog is a more careful and considered response.

While I can make a further response to the judge, I know he can’t respond publicly to this. But he didn’t seem interested in my (admittedly half-formed) response at the time, anyway. He just said that it had initially been listed in person but that was changed yesterday. For future reference, I should direct requests to observe via the hub. And I could turn my camera off now.

As I’ve already shown, the case listing never reflected the fact that this was a remote hearing. If the judge did direct it to be listed remotely, he probably imagines that did happen. But it didn’t. And I don’t have a crystal ball.

I’ve observed DJ Davies on a number of occasions. I usually find him a welcoming judge. In fact, I often suggest that new and/or nervous observers attend cases that this judge is hearing.

But if this was my first time observing, I wouldn’t want to go back.

How unfair judicial criticism hinders transparency

I’m not the only observer to feel unfairly criticised by a judge.

In April 2025, Clare Fuller, an experienced observer, requested the link to observe a hearing before Senior Judge Hilder. She sent two chasing emails (so three in total) before giving up – only to be sent the link after the time listed for the start of the hearing. She joined the link as soon as she got it, whereupon she was admonished by the judge for making a ‘disruptive’ late access request. She was told to “consider that, in the future”. In the comments section of the blog, another observer (Amanda Hill) who was already in that same hearing, says she was “mortified” when she saw the “dressing down” delivered by the judge.

The comments on that blog are a revealing read.

Celia Kitzinger recounts a story of a new observer who requested to observe an 11am hearing before HHJ Beckley. The observer was sent a link with the notice that the hearing would start at 12 noon. Those of us who are experienced observers would have suspected a mistake and would have checked. But the observer (not unfairly) assumed that she had been sent the most up-to-date information. She joined the link just before 12 noon only to find that the hearing had concluded.

But it didn’t end there. She later received a message from the court: “HHJ Beckley is sorry that you were unable to attend this morning’s hearing as an observer. There may be various reasons why you could not attend, and he doesn’t need to know them. He would like to point out that an observer request creates work for very hard-pressed court staff and for either an advocate or judge to prepare an introduction to the case for the observer’s benefit”.

The observer was “devastated”, both because she missed the hearing and by the implied judicial criticism in the message.

Another comment is from Claire Martin. In March 2025 she had requested to observe a hearing before HHJ McCabe. She sent the email in good time but, when she joined the hearing, and Counsel for the local authority told the judge that Claire had asked for position statements, this happened:

The judge quickly and irritably interjected, saying: “I don’t know when you asked Ms Martin … these requests need to be raised far in advance … it’s a pretty unfortunate way to go about it … [telling off tone – v unpleasant] we are well into the hearing and we have important matters to discuss …..” [the hearing has just started] {These were my contemporaneous notes}

Claire says she felt “told off and humiliated […] If the court wants observers to request to observe, or request documents, “far in advance” then those involved in managing proceedings need to work out a way for observers to do so..”

In my case, I think the judge took the approach he did because he knows I’m an experienced observer (I’ve observed him many times) who knows court processes well. He also appeared to think the case had been correctly listed as a remote hearing. It therefore must have appeared as though I tried to circumvent the standard procedures, and in doing so created an extra issue for him to deal with – an issue that, amidst back-to-back hearings, he could have done without.

It’s important to say that I know I’m not immune from criticism, here. What I thought were my reasonable efforts to get clarity about whether this hearing was going ahead, and then my further attempts to get the link, seem to have created problems for HMCTS staff. Those miscommunications and misunderstandings swirled around a judge who probably didn’t even have time for a cup of tea (or however else he likes to relax) between hearings. And before he could have lunch he had to deal with a case that he anticipated to be between two litigants in person who hadn’t filed position statements, and the paperwork he did have was pretty bare bones.

It wasn’t my intention to exacerbate those stresses and, in future, I’ll just send any and all correspondence direct to the hub. That’s what I’ve learnt from this experience. I hope there’s some judicial learning from this experience, too.

The irony is that it’s because I’m an experienced observer that I took this somewhat unorthodox approach. New and inexperienced observers might have just turned up at the physical courtroom, expecting an in-person hearing, as listed. I know, from experience, that hearings are sometimes vacated (or move from in person to remote and vice versa) after the list has been published. I also know how to use CourtServe in such a way that means I can find the court’s contact details. And I know that telephone calls often go unanswered, so an early morning email is a good way to catch someone’s eye.

What does all of this tell us? I think it demonstrates that judges think that gaining access to observe a hearing is simple and straightforward. When things go wrong, experienced observers are frustrated but unsurprised. By contrast, judges appear both frustrated and surprised. From there, the default position seems to be (often) to assume the problem lies with the observer – though I know some judges are well aware of the problems we observers face when trying to gain access to a hearing.

We all know that the justice system is under-resourced, under-funded, and over-stretched. Requests from observers are one more task for busy court staff to process. And sometimes things will go wrong. When they do go wrong, the judicial aspiration for open justice is hindered because (at its worst) members of the public are excluded from hearings that they have every right to attend.

Judges are also over-stretched. But, to put it rather bluntly, they have the most power and status in their courtroom. They set the tone – and that tone must be one of civility. Open justice doesn’t just entail access to the court (though that is, admittedly, a fairly significant part of it). Open justice also entails an (at least implicit) suggestion that observers are welcome, because transparency matters, even at some cost to the court. If they feel rebuked, or unwelcome, this is a significant deterrent to observing again.

The interesting thing is that all of the judges mentioned in this blog are generally what I’d describe as “good” on transparency – and these were exceptional events. I’m pretty confident that the judges concerned did not intend to cause any offence to observers – which is why it’s important for them to learn that they did, so that they can be alert to the effects of their actions in future.

I don’t expect judges to get out the bunting every time an observer attends their courtroom. But I do expect them to treat us with courtesy. It’s a depressing experience to read that observers trying to do their civic duty for transparency and open justice are left feeling “devasted” or “humiliated” by the judge – who (they feel) is “irritable” and “unpleasant” to them, and has given them a “telling off” or “dressing down”. It doesn’t happen often but when it does happen it leaves a lasting impression. Each time a judge behaves in a way that leaves observers feeling like this it makes it just that bit less likely that whoever is observing them will want to do so again, or will advise others to do so.

That’s bad for transparency. And anything that’s bad for transparency is bad for the justice system.

Daniel Clark is a member of the core team of the Open Justice Court of Protection Project. He is a PhD student in the School of Sociological Studies, Politics & International Relations at the University of Sheffield. His research considers Iris Marion Young’s claim that older people are an oppressed social group. It is funded by WRoCAH. He is on LinkedIn, X @DanielClark132 and Bluesky @clarkdaniel.bsky.social.