Alice Ferguson – 1st October 2020

I observed a telephone hearing (COP 13534031) before Senior Judge Hilder at 10.30am on the 17th September 2020.

The Start of the Hearing

There were several people involved in the hearing: including the judge, the applicant ‘C’ (P’s cousin), C’s representative, P’s representative, counsel for the local authority (the ‘LA’), P’s social worker, and me as an observer. There were others present on the call, however their roles were not introduced and they spoke very little or not at all. The callers appeared familiar with one another before the hearing began. In terms of my ability to understand who was present and what their role was, there was also the issue of people talking over one another when Judge Hilder began checking who was on the call, meaning I could not hear all of what was being said (others stated the same).

Throughout the call, the discussion about P’s welfare was primarily discussed between the Judge, and P’s cousin C, and her legal representative, and later with the local authority representative.

Before attending this hearing, I had heard and read much about the issues presented by telephone hearings, with one service user describing the process as inhumane. However, with the country still well within the grips of the current pandemic it is crucial that hearings can go ahead without needlessly bringing several parties together in a courtroom.

There were, indeed, problems with background noises of various callers interrupting Judge Hilder and causing some (albeit minor) confusion with those present on the call. Judge Hilder muted callers who were not required to speak and for the most part this was sufficient. There were, however, other issues at hand: the applicant, P’s cousin, complained of previous telephone hearings cutting out and said she also struggled to understand some discussions due to partial deafness. She also reported difficulties in contacting P who currently resides in a care home.

These issues underline the struggle that is very real for many COP participants, especially for those who are not present as professionals: what is already so commonly a stressful and confusing process can be amplified by the complications of modern technology. Overall, though, the hearing went relatively smoothly. Judge Hilder ensured all parties were clear on what was being discussed and repeated or simplified anything that caused uncertainty.

The Case Before the Court

Due to not being present for previous hearings regarding P’s welfare, I had to pick up a sense of P’s current circumstances throughout the course of the hearing (there was no formal introduction). P is in her 80s and has been diagnosed with vascular dementia. This has left her unable to care for herself and she currently resides in a care home. She has some idea of her current circumstances, and frequently mentions her previous home (before care) and has a close relationship with her extended family. This includes C (the applicant), other cousins, and a goddaughter. The hearing also discussed plans for P’s care, her capacity and the finalisation of a care plan.

The deputyship application therefore had to be addressed first in the hearing because a change would impact the plans for P’s care.

P’s cousin, C, was applying to terminate court-appointed deputyship and instead take the place of deputy herself. From the nature of the conversation, it appeared that the current deputy had been appointed by the court to handle both P’s financial and her personal affairs. C had made applications to take over each of these roles. Under Re M, N v O & P [2013] COPLR 91, Senior Judge Lush stated that the “order of preference” for deputies began with family members of P, and considered the emotional as well as economic benefit of this (professional deputies charge for their services). It was not discussed in this hearing why C was not initially made a deputy for P in either capacity. Judge Hilder was, however, mindful of costs. Rather than multiple hearings, she requested that those present at the current hearing email each other where possible to avoid such expenses and instead organised a singular, final hearing (the date of which is confirmed at the end of this article).

Under section 16(2)(b) of the Mental Capacity Act 2005, the court has the power to appoint a deputy on behalf of P where P lacks capacity to make decisions for matters concerning P’s personal welfare or P’s property and affairs. C wished to take the place of this deputy through a Court of Protection application – her argument being that she did not feel comfortable with a court-appointed stranger managing P’s personal and financial affairs.

The court first heard about a COP9 application made by C to take over the role of deputy in place of the court-appointed one to make decisions about P’s welfare. As stated on the government website, a deputy is only appointed by the court if is believed to be in a person’s best interests to do so.

Summary

C explained that in their country of birth, elderly relatives rarely go into care homes (where P is currently residing). Instead, the elderly are cared for at home until death. This is a tradition that C and the family wish to continue. In accordance with this wish, the control of property and decisions about P’s welfare should, they believe, be determined by family members. C said:

“I want to help [P] live her life the way she wants to live it. I want to buy her the food she likes; I want to take her shopping; I want to keep her in touch with extended family outside of the UK. I believe this is my job.”

C (the applicant)

Judge Hilder accommodates C; she allows her to explain clearly and completely why she wishes to be appointed as both finance and welfare deputy in place of the professional. (C speaks for herself for most of the hearing although her representative occasionally joins in).

P’s social worker adds to C’s argument. C “does not feel that her voice is being heard … a deputyship is about accommodating a family feeling”; with the power of deputyship, C feels she can truly fulfil this role. C is also concerned that the locks have been changed by the deputy in a breach of what he is authorised to do. Finally, she mentioned that she had not felt involved enough in the process because the deputy was not frequently in contact with her; “we did not hear from him at all”.

In Re BM, JB, v AG [2014] EWCOPB20, Senior Judge Lush explained further on the point of familial deputies. He stated that although the ‘court has preferred to appoint a relative or friend as deputy’ because ‘a relative or friend is usually familiar with P’s affairs and aware of their wishes and feelings’, it must be in P’s “best interests” to do so.

When C has finished explaining her wishes, Judge Hilder politely but firmly reminds C about the point of the deputyship. The point is to support P; to protect and serve her best interests, and her best interests alone. The deputyship does not exist to do this for both P and C. The court has appointed the deputy because the deputy is, and continues to be, in the best position to ensure P’s welfare.

Judge Hilder frequently reminds C and her representative that P should remain the focus. There may have been an application to remove the court-appointed deputy, but it is crucial to remember why a deputy had been appointed in the first place – to serve P’s best interests. C may want to accommodate P’s personal preferences, and she may be in the best position out of those present for the hearing, but P’s needs extend beyond familiarity.

The judge then explains that the act of changing the locks is an authorised act. Finally, on this point, she states that the deputyship may be open to change or extension, but this is not being dealt with at this moment in time. C’s application was rejected.

C interjects. What is further concerning her is the deputy’s power to enter P’s household and remove her personal belongings. This appears to be a reference to the financial deputyship that the court has arranged for P. C explains her anxiety that sentimental or valuable items belonging to P and her family would be incorrectly disposed of. C wants her cousin to have a say in what is, or is not, kept.

What the appointed deputy doesn’t know is:

“what is special to P. A [court-appointed deputy] will not know whether this or that item is from her wedding, from a relative back home, from a special occasion [for example]”.

C (the applicant)

C is clearly distressed, understandably so; it is an uncomfortable notion for many people to envision a stranger deciding which of their possessions are and are not worth keeping. Belongings are, after all, often a reflection of our lived experiences.

“I accept your concerns and share them”, Judge Hilder responds. “We will deal with this issue as we progress through the draft order.”

It is confirmed that, pursuant to section 2 and section 3 of the Mental Capacity Act 2005, P lacks capacity to make decisions about her care and where she should live.

All parties agree with this; the doctor’s opinion (which was referenced from a prior meeting between P and the doctor) is that P will not regain capacity. C does express further concern: just because P lacks capacity to make decisions about her care and accommodation, this should not mean her wishes about remaining in a care home should be ignored. C is demonstrably distressed and emotional throughout this process. Judge Hilder sometimes has to mute the telephone line of C during the hearing to direct the conversation into something orderly.

Although this may sound, upon reading, as though it could be an unfair advantage of a Judge (and arguably it could well be utilised as such), the muting was appropriate in some situations and no party objected. Judge Hilder would quickly unmute the telephone line of C and explain that she had just done so and why. This happened just a few times (about 2 or 3) and the issues C raised in the moments before muting were addressed as the parties discussed each section of the draft order.

Judge Hilder explains the power of a deputy under the MCA 2005. Under section 16, court-appointed deputies have the power to make decisions about a person’s property. “A property is hardly ever cleared without direction from the service user or family”, she continues. C, and other approved family members, can help. “There is no issue with this.” The financial and welfare professional deputy, therefore, could remain without preventing C’s involvement.

C agrees that this is fair. However, P’s house is “very, very important to her [P]”. C suggests that P visits the house to personally direct what items should or should not be removed. P is “talking about [her] house all the time. All the time.”.

Judge Hilder acknowledges this. “There are certainly positives to accommodating [P] in this regard”, but what about the risks? She refers to counsel for the LA.

The counsel for the LA agrees there are positive aspects to P being involved in the process, but the idea also raises concerns. Firstly, she continues, is the very real risk of introducing stress for P. There are photographs of the property in its current state. The house would need to be cleared of items that are definitely not belongings (e.g. items that are clearly rubbish). P is also not fully mobile and may be confined to the ground floor due to accessibility issues.

This again underlines the difficult balancing act present in many COP cases. When a loved one loses capacity, it is instinctual to want to protect them and to feel empowered throughout the process. However, what family members want and what is best for the service user cannot always align.

The counsel for the LA and Judge Hilder discuss what can be done to accommodate P whilst avoiding potential problems. It is suggested that a list of items that P wants to keep may be a useful option if it is not possible to bring her to the house. C is invited to make the list and to check with other relatives so as to ensure all valuable possessions are retained.

C states that there has been difficulty in contacting P via telephone during the pandemic; often she rings the care home and receives no response. It is accepted by both C and the Judge that the current pandemic has introduced further barriers to organisation, but this cannot be helped.

C’s legal representative then begins to talk; he wishes to remind the court of Articles 3 and 8 of the Human Rights Act 1998 (to be free from torture and inhuman or degrading treatment and a right to a private and family life respectively). The representative reiterates that the court must consider the familial role of the cousin and her wishes for P’s care (namely that C wishes to take P into the family home).

The mention of Article 3, in this context, could be suggesting that P should not have to endure care that does not accommodate her wishes, including her right to be with her family (Article 8). If so, C’s representative would likely have been referring to the prevention of inhuman or degrading treatment of P through care that would not fulfil her desire to be with her family. It is uncommon for Article 3 to be referenced in discussions of care proceedings, with Articles 6 (the right to liberty and security) and 8 being more frequently referenced.

I must mention here that Article 3 could also suggest the opposite. P has a right to care that is sufficient for all her needs. This includes 24-hour care, which may not be possible in the family home (at this point, arrangements for P’s care in the family home were not complete). To place a vulnerable person in a care setting that cannot serve their best interests is arguably more likely to lead to an Article 3 infringement than to deprive a person from a family’s care. There is also the question of whether P’s treatment would ever reach the level of severity that is required to qualify a discussion of Article 3 (one hopes this would never be relevant). Article 3 has been stated as requiring a minimum threshold of severity for treatment to be considered under its scope which is relative to each case (Ireland v United Kingdom (1978)). This assessment of Article 3 is speculative, however, as C’s representative did not explain his reference to it further.

Judge Hilder reminds the representative that what C wants for P, and what P wants for herself regarding aspects of her care may not be the same. “It is not compulsory for P to agree with her cousin on all matters of her care” and it is therefore important to consider P’s personal wishes for her care as far as it is possible to do so. Ultimately, P’s Article 8 rights may not completely align with C’s, and it is P’s rights that must be the focus in this hearing.

Details are agreed; a list must be drawn up by P and her family as to what their plans are for living arrangements (if, in future, P moves from the care home and into a family home in line with the family’s wishes), what belongings should be kept and further discussion on how far P can be involved in the process. This involves C needing to provide a detailed plan on how P will be cared for and who will care for her when the family cannot be at home.

Further, C needs to confirm whether she would be willing to move to a different area in order to care for P as they currently live relatively far away from one another. Finally, the statement should include any properties C or the extended family have found that would be suitable for P to reside in should she move from the care home.

The local authority also needs to file a statement concerning a care package. This should include costs, type of accommodation needed, care services including the consideration of personal assistants (depending on whether P does indeed move to a private home or remains in a care home). The local authority should also state what accommodation it prefers, including a different type of care home if that is deemed suitable.

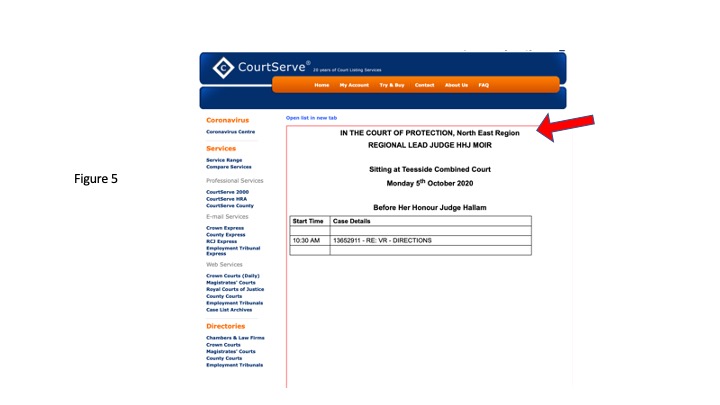

All parties agreed on the next steps and a date for the next hearing (about where P should live and how best to care for her) was confirmed. This will be the 20th October 2020 at 10am in First Avenue House, London. The current plan is that it will take place in person (not remotely) and it is scheduled to last the entire day.

Due to the next hearing taking place in person, I cannot observe it. However, I am confident that Judge Hilder will continue to strike a balance between P’s needs and the wishes of her family. COP hearings often centre around sensitive and emotional issues, and it was reassuring to witness a judge who acted with empathy for the family’s concerns whilst ensuring that P remained the primary focus. Judge Hilder skilfully found solutions to empower both P and her family throughout the process by suggesting ways to involve them as much as possible.

Alice Ferguson is a Bar Practice Course student with an interest in civil and social rights. She tweets @aliceferguson_

Photo by Raychan on Unsplash

References

https://www.injusticewatch.org/news/2020/challenges-arise-as-the-courtroom-goes-virtual/ (Comment on effect of remote hearings)

https://www.39essex.com/cop_cases/re-m-n-v-o-p/ (Reference to Re M, N v O & P)

https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2005/9/section/16 (Reference to s16 MCA)

https://www.gov.uk/become-deputy (government deputy web-page)

https://www.bailii.org/ew/cases/EWCOP/2014/B20.html [Re BM [2014] EWCOP B20]

https://childprotectionresource.online/article-3-echr-and-care-proceedings/ (discussion of Article 3 and care proceedings)

http://hudoc.echr.coe.int/eng?i=001-181585 (Ireland v United Kingdom (1978))

https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2005/9/section/2 (Section 2 MCA hyperlink)

https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2005/9/section/3 (Section 3 MCA hyperlink)