By Claire Martin and Nell Robson, 13th June 2024

This is a case we’ve blogged about before: “Caesarean: A directions hearing”.

At that point, just under a week before, Deputy High Court Judge Victoria Butler-Cole KC, asked for a full-day final hearing to deal with an application for a court-authorised caesarean for a woman who (probably) couldn’t give consent to it. She asked for oral witness evidence for the court. She also asked whether the protected party wanted to talk to the judge directly.

But it wasn’t DHCJ Butler-Cole KC who heard the case today (30th May 2024). It was Mr Justice Cusworth – and the hearing was over and done with in 14 minutes, with no cross-examination of witnesses (although they were in court) and no mention of whether or not the protected party had spoken with the judge. Cusworth J authorised the caesarean – with restraint if necessary.

This blog is split into three sections: [1] Transparency Matters; [2] The Decision of the Court; and [3] Reflections.

1. Transparency Matters

The Court of Protection (CoP) is committed to open justice. Sometimes this is hard to achieve in practice. It takes a lot of steps to get the ducks in a row.

Hearings have to be listed correctly for the public to know when a case is being heard, to enable them to decide which cases to observe. We observers then email the relevant court to request the link to observe. Someone at the other end needs to read the email and provide the link, in time. So far, so good. If the hearing is hybrid, like this one (meaning that people are in the physical courtroom as well as there being a remote link to attend and/or observe), ‘open justice’ also means being able to see and hear the court in action. This is more difficult than when the hearing is fully remote and everyone can be seen and heard more easily (because everyone is on screen in their ‘cell’ and each person is – usually – directly in front of their computer microphone).

Knowing who everyone is, is much easier in fully remote hearings too, because people’s names are normally attached to their image on the screen. Open justice means knowing who we are watching and what their roles are. We often rely on counsel to introduce themselves so we know which party they represent. Celia Kitzinger commented in her blog on the lack of transparency in the previous hearing for this same case: “I often recognise the lawyers – if not by sight (which can be hard when they’re be-wigged, though they weren’t in this case), by sound – but in this case I had no idea who the applicant lawyer was. I eventually figured it out when the lawyer for the Official Solicitor said, about half way through the hearing “Mr Rylatt and I have had some discussion…” – and bingo! I recognised him as Jake Rylatt, a lawyer I’ve watched before (albeit infrequently) in several hearings. I doubt those observers who hadn’t already come across Jake Rylatt would have picked this up.”

Observers should also be served the ‘Transparency Order’ which is the court injunction telling us who we cannot name in any reporting (almost always P, the protected party, and their family, but sometimes other information is included in the injunction).

Sometimes there are a few ducks not quite lined up, or totally out of the picture altogether.

Getting the link

When court listings are posted via Courtel or on the Royal Courts of Justice website (at around 4-5pm each weekday evening) the Open Justice Court of Protection project reposts all CoP hearings on our Twitter/X feed each evening and adds ‘featured hearings’ on the website and Facebook page.

So, we emailed the Royal Courts of Justice the night before to request the link and Transparency Order. Claire received an email at 08:27 (and Nell shortly after that time) the following morning, informing us that our request had been forwarded to ‘VHA and associate team who will be able to action your request’. That was very welcome. Sometimes responses are not received until very close to the start of a hearing, and we might then email again – bothering busy court staff – to chase up our original request in case it has gone astray.

The hearing was due to start at 10.30am and Claire received the link at 10:09am. So did Nell Robson.

But Ruth Fletcher (a legal academic working on reproductive rights at the Queen Mary School of Law in London) requested the link for this hearing before we did. She emailed on Tuesday 28th May. We emailed on Wednesday 29th May. Ruth received a reply from the court on Wednesday 29th May but she didn’t receive a link for the hearing, and ten minutes before it was due to start, she emailed again. She also telephoned the number for the Royal Courts of Justice and got no reply. She finally received the link at 11.19am (almost 50 minutes after the scheduled start of the hearing). This is not open justice. The system for collating and responding to observer requests seems to be fragmented and piecemeal, and it is down to pot luck, at times, whether you receive the link in time to enable you to observe. Fortunately for Ruth, the start time of this hearing was delayed until 11.25am, but the difficulty gaining access would put a lot of people off.

Joining the hearing

The hearing was on Cloud Video Platform (CVP). There are a few steps in joining a CVP hearing. You add in your name, then you have to click whether you are joining with ‘video+audio’, ‘audio only’, ‘presentation only’ or as an ‘observer’. I (Claire) have previously clicked ‘observer’, but this choice automatically joins you muted and with your camera off, and you cannot change it once you are ‘in’. In a previous hearing, the court clerk was speaking to me directly to check I could hear and see (which I could), and I couldn’t reply! On that occasion, I wrote in the chat box that I was unable to respond because I had joined as an ‘observer’. So, for this hearing I clicked to join with ‘video+audio’ so that I could respond if the clerk asked whether everyone could hear – which she did! (The fact that joining as an “observer” causes problems for court staff like this is evidence, presumably, of a lack of consultation with them about how the system works in practice.)

The downside of joining with ‘video and audio’ is that, unlike MS Teams, with CVP you cannot switch off your camera prior to being admitted to the virtual courtroom (there’s a small tick box for joining the link with microphone off). So, I always make a mental note to remember to locate the icon for it the moment I am admitted and switch the camera off. It is at the middle-bottom of the screen!

A further step before being admitted is needing to enter the PIN number for the hearing (which is in the email that the court staff send with the link to join). It’s so easy not to know how to get through all of this and to find it quite intimidating. And all of this is before you are in the ‘virtual’ courtroom observing proceedings.

For a helpful explainer on how to access CVP see here: How to join Cloud Video Platform (CVP) for a video hearing

Problems joining this hearing

The hearing was listed for 10.30am but as noted didn’t, in fact, start until 11.25am. It’s not uncommon for a hearing to be delayed for all sorts of understandable reasons. As an observer on the link with the periodic voiceover saying ‘Waiting for the conference host to join’ it can start to feel unsettling when time draws out. We were worried we might be on the wrong link (two different emails had been sent with a link), or that the link had changed.

Claire emailed the court staff at 11.10 to check we were connected to the right link (and also took that opportunity to ask again for the Transparency Order).

At 11.16 we were connected and there was the sound of people sorting out chairs and the court room. Court staff asked if everyone could hear, so Claire switched on her mic and confirmed that we could hear. The hearing got underway at 11.25am, almost an hour after it was listed to start. It’s worth ensuring you have some time around a hearing’s listed start time and length as often they start late, and we are (usually) not informed of delays or how long a delay may last.

Who’s who in court

In hybrid hearings – like this one – it is often difficult to know who is who in the courtroom. Others on the remote link are listed, so at least names are known, if not roles. We rely on the key people to make themselves and their roles known. In this hearing, counsel for the NHS Trust was invited by the judge to open proceedings. He might have said his name, but I didn’t hear it. I think it was Jake Rylatt, counsel for the applicant NHS Trust, as the week before.

Counsel for HW was another man, though in the previous week’s hearing it had been Katie Gollop. We don’t know who was representing HW today because he spoke for a very short time, just answering a query from the judge on one occasion, and we didn’t catch how the judge addressed him.

There were others in court – who Jake Rylatt said were the psychiatrist who had assessed HW’s capacity for making decisions about her obstetric care, and (we think) a consultant in midwifery. We think there were also instructing solicitors sitting behind counsel, as is usual.

The judge was not on any screen on the remote link. Celia Kitzinger commented on this experience, see here: “There was no camera on the judge. There’s something quite unsettling for those of us concerned with open justice for the judge to be nothing more than a disembodied voice in a video-hearing. Just on principle, judges shouldn’t be invisible!”. So, Mr Justice Cusworth’s disembodied voice was heard every now and then, speaking to counsel and asking for information. This surprised me for a court at the Royal Courts of Justice. I have observed other hearings there, where the judge, counsel and any witnesses giving evidence could be observed at the same time (via different cameras).

The Transparency Order

There was no Transparency Order attached to the emailed remote link to observe (recently, I have often had TOs sent with the hearing link) and Claire emailed back straight away, thanking the court staff for the link and re-requesting the TO. However, the TO wasn’t received it prior to or during the hearing. We still don’t have the TO though have requested it twice and have also requested the sealed court order to try to better understand the reasoning of the judgment. We believe that we are entitled to request these documents under COP Rule 5.9 :

The judge has agreed to our request for the order (via email with his clerk), but it has not yet been received nearly two weeks later.

The TO was mentioned, however, at the start of the hearing by Jake Rylatt. He said “For the benefit of observers, the TO material covered by the injunction is any material identifying that P is a subject or P’s family, any information identifying where any people live or are cared for or any contact details and identification likely to identify hospital staff and the prison – she was on a 14-day recall, she’s no longer on this….”

This is what I (Claire) have come to understand as the ‘standard’ injunctions in a TO – which are principally in place to protect the privacy of ‘P’, the person at the centre of the Court of Protection case, and anyone associated with them, such as their family members, where they live and so on. We have found that TOs are not always in their ‘standard’ form when (and if) we do receive them. Sometimes they include, as part of the subject matter of the injunction, a Local Authority, an NHS Trust or even the Office for the Public Guardian (see this recent blog). We might inadvertently identify these bodies if we do not receive the TO, and we are also unable to request that the TO is ‘varied’ (changed) at the time of the hearing, to enable identification of public bodies, if we don’t receive the TO in a timely fashion.

Opening summary

If cases have not been blogged about or observed before, we know nothing of the case or what the issues are for the court on that particular occasion.

At this hearing, there was an clear and helpful opening summary from Jake Rylatt, consistent with the guidance from the former Vice-President of the Court of Protection. The judge in this hearing stated explicitly that an opening summary would be helpful, not least because there were observers present. Such explicit support for open justice from the judiciary is very welcome.

2. The decision of the court

The previous blog post about this case ends with this: “The judge pointed out that “the legal framework isn’t going to be contentious”, and then listed the hearing for the whole day on Thursday 30th May 2024 (rather than the half-day requested by the Trust) “to give time for a remote visit [i.e. a conversation with HW] and for the judgment, which you’re going to need as soon as possible”.”

We didn’t find out, in the hearing, whether HW had spoken to the judge in a ‘remote visit’. HW was said, now, to be in agreement with the authorisations sought – a planned Caesarean section. She was, however, deemed to lack capacity to make this decision for herself and the Official Solicitor (OS) was in agreement with the NHS Trust that this was in her best interests. I don’t know whether the OS was previously opposed, or whether they sought more information. At the previous hearing, there was certainly a question about whether HW had, or would, regain capacity and thus make the decision for herself (which could well have been to have a Caesarean). An up-to-date capacity assessment had been completed:

Counsel for the Trust said: ” Further assessments by Dr A (consultant psychiatrist), with support of the MDT around [HW], last week and Tuesday [this week]. All three concluded that she lacks capacity regarding obstetric care. [It is] agreed by the OS that [HW] lacks capacity for proceedings and her obstetric care. The court is invited to make Section 15 declarations [about lack of capacity for these decisions].”

There were clinician witnesses in court, and the hearing had been allocated a whole day, but the hearing quickly moved to the (joint) current position of parties being submitted to the judge. The position, now supported by both parties (the applicant NHS Trust and the Official Solicitor for HW), was that it was in HW’s best interests to undergo a planned Caesarean section on the 3rd June 2024, with chemical and physical restraint if necessary. Jake Rylatt presented the proposed care plan to the court as follows:

“[The plan is] for a c-section on Monday 3rd June – this is consistent with her wishes and feelings expressed over the last week or so, supported by psychiatry and midwifery and based on psychological trauma and harm [that would occur] during an induced vaginal birth. Parties are satisfied that a c-section is in her best interests. The updated treatment plan: spinal anaesthetic then general anaesthetic under specific circumstances – one, if she requests it; two, if she’s insufficiently cooperative, or three, if there’s a clear clinical reason for general anaesthetic – that will be assessed on the day. C-section and anaesthesia is set out in detail in the obstetrics care plan. Restraint is set out in a stepwise manner … p179 of the bundle. The crux of the plan is contained in a stepwise plan for management. It essentially envisages that verbal de-escalation will be tried, then oral PRNas prescribed, Lorazepam; failing that, intra-muscular PRN will be administered, then there may be need for physical restraint. The safest manner, taking in to account NICE guidelines, is to use a safety pod and [?]. If that process is not successful at deescalating, then the plan is for review by an anaesthetist and further sedatives as required. It is only anticipated that restraint is required … [lost] if restraint beyond that in emergency … [lost] it’s very much hoped that won’t be necessary and indeed [HW] has been compliant with interventions to date [Jake Rylatt went on to express that this won’t necessarily be so during labour].”

There was brief mention of Deprivation of Liberty being taken out of the agreed draft order and then the judge invited Jake Rylatt to take the court to the draft orders, which confirmed the above declarations (that HW lacked capacity to make obstetric decisions) and authorised the care plan described.

The judge said:” I am quite content with the treatment order, subject to the spelling of the word foetal“.

And, after an agreement about how long the TO should last for (three months) and counsel for the OS [whose name I did not hear] confirming his agreement to the draft order, that was it. A 14-minute hearing.

3. Reflections

We’ve presented our reflections separately.

Nell Robson’s reflections

Having just completed an EPQ researching the making of best interests decisions for pregnant women and the common challenges that arise, this case seems to fit the trend exactly. Repeated challenges or issues in the cases I looked at included:

- The evident lack of time in most cases, due to applications for pregnant women being brought to court late in the woman’s pregnancy – as is applicable to this case, as HW was 38 weeks pregnant at the time of the hearing.

- The difficulty in ascertaining whether a patient lacks capacity – HW’s lack of capacity seemed (from the directions hearing that Celia Kitzinger blogged about) to be predicated on the fact she would not accept that she was pregnant. However, by the time of the hearing that I was observing, HW had accepted that she was pregnant – and yet it was not made clear (to observers) why she had been judged to continue to lack capacity to make birth decisions.

- The position that tends to view pregnant women (especially women with severe mental illness [SMI]) as ‘risky’ rather than a person at risk or vulnerable themself.

- The problem of when the woman’s voice being clearly missing from the hearing. Best interests decisions must consider the wishes, beliefs and values of the person concerned. At this hearing it was stated at the start of Jake Rylatt’s submissions that the proposed care plan “is consistent with her wishes and feelings expressed over the last week or so”. But HW was not at the hearing and therefore did not speak for herself, Counsel representing HW (via the Official Solicitor), who we don’t know, did not speak at all about HW’s expressed wishes and feelings and neither did the judge. Although of course, HW might have spoken to the judge at some point, it felt that her own views, and therefore her voice, was entirely missing from those who might have spoken to her said at the hearing. This seems common in cases I have read for pregnant women in the CoP.

In the very swift judgment, it was ruled that a general anaesthetic may be resorted to if a) HW states that she would like one, b) if she is ‘insufficiently cooperative’, or c) if there is a clear clinical reason for one. The choice of phrase of ‘insufficiently cooperative’ feels concerning to me. It creates the idea that, potentially due to her lack of capacity, she should have no say in her treatment if her views are contradictory to those of her medical team. Surely, her voice should be listened to and respected much more than it is appearing to be? It also seems to position HW as the issue, that her wishes are obstructing the path that the doctors wish to take, rather than her wishes being something that should be used to inform her care.

The largest concern that I felt when observing this case was that the voice of HW was entirely absent, both in that she was not present at the hearing, nor were her views towards her treatment explained adequately at any time. As I had not observed the previous hearing concerning this case, I understand that her wishes and feelings may have been expressed then, however I think that it is still important to restate her wishes when making the final judgment/declaration. It was only counsel for the applicant Trust who mentioned them at the hearing. There was no questioning of the submissions at any point (apart from a small point about whether the transparency order should be for 3 or 6 months) and numerous restrictive measures against HW were authorised without any detail (spoken about in the hearing at least) about when and how such physical and chemical restraint could be used. Alongside flattening the voice of HW by permitting so much restraint with such little (transparent) scrutiny, this also returns to the issue of perceiving the woman as ‘risky’ rather than a vulnerable person who needs to be cared for and worked alongside with rather than controlled.

Claire Martin’s reflections

I know that HW will have had her baby by now. I hope that the experience was manageable for her. The information that we as observers have is that she (for the majority of her pregnancy at least) did not believe that she was pregnant. I can understand why her clinical team was concerned about the potential impact on her mental health when she went into labour.

I searched for papers addressing pregnant women who do not believe they are pregnant – and specifically was looking for research about the psychological impact on such women who go into spontaneous labour. It won’t have been an exhaustive scholarly search, but interestingly nothing about the impact on women came up. This might be because I have not searched fully enough, or used the wrong search terms, or it could be that there is no research in this area – perhaps pregnant women with mental health issues who do not believe that they are pregnant are not giving birth spontaneously, and instead are always undergoing planned caesareans.

There is substantial literature on the phenomenon of what is called ‘pregnancy denial’. It has been thought to fall into two categories: psychotic and non-psychotic pregnancy denial. This paper (from 2000) explains the phenomenon below:

This fascinating paper (from 2023) discusses potential underlying mechanisms, possibly updating the understanding of the phenomenon described in to 2000 paper above, concluding:

This paper (again US, in 2011) addresses legal as well as treatment considerations for clinicians, though of course this is in relation to US case law.

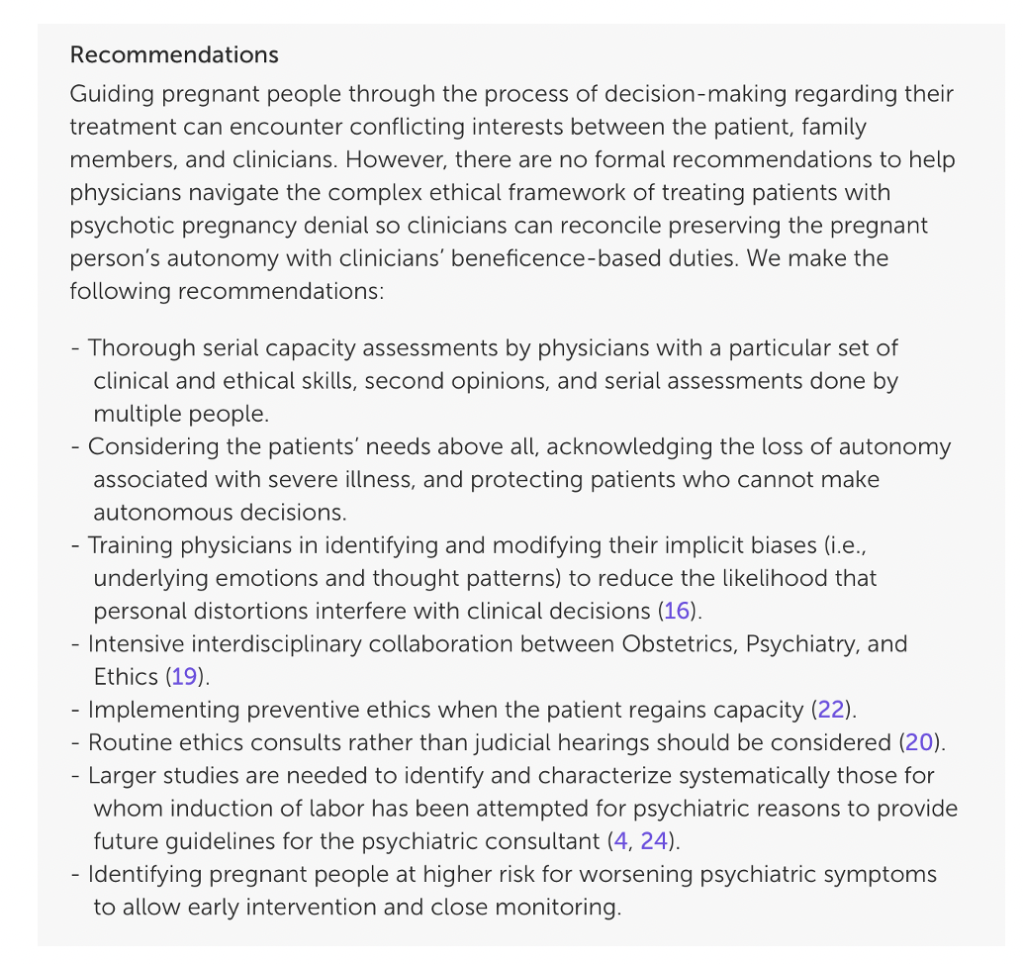

There are several papers making clinical recommendations such as here and here, and this paper (from the USA, 2024) ends with these recommendations:

However, I couldn’t find papers explaining why a planned delivery is recommended, although intuitively I can understand that this would be thought best by those looking after pregnant women. As Nell mentions above, it appears that the Best Interests decision (for a planned Caesarean section, with restraint if deemed necessary) was based upon HW’s belief that she is not pregnant, and the MDT’s assessment that she would be distressed by giving birth naturally. Celia Kitzinger said in her blog, “I can imagine that going into labour would be very frightening if you didn’t believe you were pregnant” – but this was simply speculation from Celia about why a caesarean might be in HW’s best interests and not based on anything made explicit in court. So, I simply don’t know.

It would be interesting to know if this scenario (going into labour when you believe you are not pregnant) has been researched and reported and what this was like for the women, any subsequent impacts on their mental health, relationships with their babies or other consequences. My (albeit brief) literature search suggests that current practice is based on what others believe is the right way to help women in ‘pregnancy denial’ to give birth, rather than evidence-based practice. I would really like to know if there is research that I have not found about this interesting and very important area.

In this hearing, I was most struck by the decision of lack of capacity very swiftly being accepted by the judge, given that, only a week previously (at the directions hearing before DHCJ Butler-Cole) there was a possibility of HW regaining capacity, which would have enabled her to make her own decision about whether to have a Caesarean section. In this scenario, I was unsure why the judge didn’t scrutinise the capacity assessment more – especially given that the psychiatrist who did the assessment was in court ready to give evidence. Perhaps, since he and counsel all had the relevant paperwork (and I didn’t) it was all uncontroversial by now. However, to understand how the law operates and how decisions are made – especially very intrusive and draconian decisions such as these – a clear public record of how capacity and best interests decisions are reached should be (I would argue) mandatory. Otherwise, how do we know that this is not just the Trust wanting to do the easiest and clinically safest thing from their point of view? I don’t know if there will be a published judgment for this case, which would, of course, provide that public record.

Restraint plans were spoken about vaguely (presumably there are details in the approved order) but included chemical and physical restraint if HW was ‘insufficiently cooperative’ (with only a spinal anaesthetic for the Caesarean). It might be that the court order has the detail about the clear steps for chemical and physical restraint and when they are allowed, and I haven’t had the opportunity to read that yet. If it does, I will update this blog accordingly, to reflect accurately the judicial decision-making process.

I know that this is the stark reality of caring for people who might become upset, angry, potentially aggressive and violent. I think that the language used, however, is unfortunate and positions others in a powerful ‘doing to’ role with HW. For example, the phrase ‘insufficiently cooperative’ is probably how staff will see HW if this is the language used in the court order and care plan. I wonder how staff might feel about HW, and their own role(s) in relation to her, if, for example, the plan was phrased in terms such as: ‘If HW changes her mind at any point about her obstetric care, becomes distressed and is asking for a different birth plan’? ‘Changes her mind’ is different to ‘insufficiently cooperative’, gives HW some agency and respect for her own views and continues to afford her wishes and feelings some respect and weight during the process of giving birth. It would frame the entire process dialogically, rather than position HW as a subject who is either ‘cooperative’ or ‘uncooperative’ in relation to others’ plans and powers. Of course, when a best interests decision is made for someone, it is not their decision to ‘change their mind’ about. However, given that the birth plan and court order were determined in the context of HW agreeing with the decisions in them (her wishes and feelings were mentioned and were said to be the same as her clinical team’s), her views were therefore presented as a relevant part of the best interests determinations.

Sam Halliday’s recent paper on pregnancy and severe mental illness discusses the framing of women with mental health problems as ‘risky’ rather than ‘at risk’ and vulnerable themselves. I thought that HW was positioned this way. She was seen as a risk – of becoming uncooperative with the clinicians. I wondered whyand under what circumstances she might move into this position. There was no judicial scrutiny of the details of this scenario (at the public hearing). We didn’t learn any details of a stepwise plan, in terms of what HW would need to be doing to enable chemical and physical restraint to be applied. Jake Rylatt stated the following: “Restraint is set out in a stepwise manner … p179 of the bundle. The crux of the plan is contained in a stepwise plan for management. It essentially envisages that verbal de-escalation will be tried, then oral PRN as prescribed, Lorazepam; failing that, intra-muscular PRN will be administered, then there may be need for physical restraint. The safest manner, taking in to account NICE guidelines, is to use a safety pod and [?]. If that process is not successful at deescalating, then the plan is for review by an anaesthetist and further sedatives as required.”

What would count, for example, as ‘insufficiently cooperative’ to trigger this stepwise plan? What were the ‘verbal de-escalation’ methods? How would they be deployed and by whom, and how many people would be around HW? Would HW only need to be refusing the c-section care plan verbally to be considered ‘insufficiently cooperative’, or would she need to be posing a risk to others or herself physically? How long would this be tolerated before Lorazepam was administered, intra-muscularly if necessary? Was there included in the plan an order to spend time discussing HW’s thoughts with her, to better understand her concerns, once she was emotionally ‘de-escalated’? I have read about and have been in other hearings (see here, here and here, the final link describes the judge directing more detail about how P is to be restrained) where these sorts of details were nailed down by the judge, to ensure that P was protected from premature intrusion and force, and also to protect professionals by ensuring that they knew exactly what they were to do each step of the way.

The key point here is that, even if this was all already-known by counsel and the judge – because it was all spelt out in the paperwork – we, the public, didn’t know the answers to any of these questions. Why would you let the public into court to observe a hearing but restrict the information available to us in such a way as to leave us anxious and disturbed about the possibility that restraint was being improperly authorised? Observers in court are likely to be writing about the case. Compulsion during labour is a (realistic) fear of many women. I’m a very experienced Court of Protection observer, but I came away from the hearing not fully understanding the basis on which the caesarean was being ordered and the circumstances in which chemical and physical restraint would be used, and how they would be deployed. This is the opposite of what the court should be doing – it’s not transparent, and it raises our anxieties about coercion.

I echo Nell’s concerns about HW having no voice – counsel for HW, who is representing her via the Official Solicitor, said nothing about HW’s wishes and feelings, her ‘impairment of the mind or brain’ underlying her lack of capacity, or how she was currently doing. HW as a person was not brought to the court room. Doing so might have humanised her more for the court. The “court” (meaning the judge) may already know a lot about her – but he didn’t say so and he didn’t tell us anything much at all – again raising our anxieties rather than allaying them. I think – across the two hearings we have observed – we, the public, know very little about HW as a person.

Overall, I left the hearing thinking that there was insufficient judicial curiosity and scrutiny of very invasive requests regarding a woman’s body. I don’t know (did the judge?) when and how HW might be subject to highly distressing restraint procedures. It might be in HW’s best interests to have a caesarean with the aim of avoiding distress and emotional trauma. That seems like a compassionate and reasonable proposal. It is, however, also known that forced treatment in itself, including physical and chemical restraint is highly likely to be traumatising (see this recent blog about a woman with anorexia for her detailed description of what this was like for her; and this paper). Significant restraint of a pregnant woman was authorised in this hearing, including the administration of intra-muscular tranquilising medications. The stated objective of avoiding the distress of giving birth to a baby HW did not think she was having did not seem balanced by concern for the potential to cause distress by the methods authorised in the order.

What about the open justice aspects of this hearing? I would say that insufficient attention was paid to this. The hearing had been scheduled – at least initially – for a full day, and it was over and done with in 14 minutes. Other bloggers (here, here and here) have expressed grave disquiet about court-ordered caesareans. This hearing proceeded as if the legal system had no idea that members of the public might feel concerned about a court-authorised caesarean or might be critical of this decision.

Another 14 minutes or so could have covered the kinds of concerns that members of the public are likely to have about court-ordered caesarean with restraint. The court could have explained the decisions the court reached and the reasons for them in a way that might pre-empt the kinds of criticisms that are routinely and publicly raised about court-ordered caesarean. The hearing, originally listed for a full day, would still have come in at under half an hour – and that extra 14 minutes would have really made a difference for open justice.

Claire Martin is a Consultant Clinical Psychologist, Cumbria, Northumberland, Tyne and Wear NHS Foundation Trust, Older People’s Clinical Psychology Department, Gateshead. She is a member of the core team of the Open Justice Court of Protection Project and has published dozens of blog posts for the Project about hearings she’s observed (e.g. here and here). She tweets @DocCMartin

Nell Robson is a sixth-form student who has recently completed an Extended Personal Qualification entitled: “What are the challenges in making best interests decisions for pregnant/birthing women?”

One thought on “Court-authorised caesarean with chemical and physical restraint if required: A 14-minute final hearing”