By Richard Lung (with Celia Kitzinger), 1st December 2024

Sometimes holding on to me to keep steady, Ella walked out of the care home lounge into the entrance hall. To staff: “I want to go home to my son. Why can’t I go home? – It’s a free country!” (Richard)

Ella Lung, in her nineties and suffering from dementia, was deprived of her liberty in a care home for just over two years: from 22nd November 2019 until shortly before her death, aged 96, on 16th December 2021.

In the Court of Protection proceedings eventually brought on Ella’s behalf by the Official Solicitor, Ella and her son Richard feature as “EL” and “RL” (EL v North Yorkshire County Council & RL, COP 13539692). There is no published judgment.

The only published record of this family’s experience of how they were treated by health and social services, and by the court, is Richard’s detailed, impassioned, meticulous account of his mother’s life, and death, across fourteen journals in a series called “Family Splitting” published online (see Appendix). The journals document interactions between Ella and Richard during the period when, in Richard’s words, “Ella suffered over two years of unjust and anguished imprisonment”. They tell an important story.

During the course of the court proceedings, the local authority legal department sent Richard a letter saying that his writing breached the “Transparency Order”: in the usual terms of the ‘standard’ order, he was not allowed to identify his mother as a protected party in Court of Protection proceedings. The Official Solicitor opined that the journals were an interference with Ella’s Article 8 right to respect for her private life. What is clear from my reading of them is the deep love, respect and admiration Richard had for Ella, and the importance for him of chronicling what was being done to his mother in the name of her “best interests”. He says Ella gave permission and was proud of her son, the writer. He says that sharing their experience may help others in similar situations.

The reporting restrictions applied “until further order of the court” – so even after Ella’s death, Richard was still unable to speak or write publicly about their experience of the Court of Protection.

Earlier this year, I helped Richard to apply for the Transparency Order to be discharged. He said in his application: “I understand that the purpose of the Transparency Order is to protect the identity of the vulnerable person at the centre of the case (i.e. my mother) and now that she is dead, there is no purpose to it. I want to be able to tell the story of what happened to my mother and to be able to make information about this case public. I understand that my right to freedom of speech (and the public’s right to freedom of information) should now trump my mother’s right to privacy (as she has died). In any case she did not want privacy about this. I have already published extensively about my mother (see: https://www.smashwords.com/profile/view/democracyscience) but have not been able to write about the role of the court due to the TO.”

Richard’s application to discharge the Transparency Order was listed for an in-person hearing at Scarborough Justice Centre in July 2024, with a direction for all parties to serve Position Statements. We are very grateful to Tor Butler-Cole for pro bono assistance in writing Richard’s Position Statement: it undoubtedly made a huge difference by providing a clear and authoritative statement of the relevant legal framework and its application to this case. She invited the court to decide the case on the papers.

And that is what happened. The local authority did not oppose and the Official Solicitor did not seek any role in the proceedings. The court issued an order on 9th July 2024 (two months after Richard’s application) vacating the hearing listed for 26th July 2024 and saying that “The transparency order dated 4 March 2021 is revoked, such that there are no restrictions on the identification of EL, any member of EL’s family or the local authority in connection with these proceedings”.

So here is (an abridged version of) Ella’s story. You can read the full story in the books listed in the Appendix.

Ella’s story

On 11th August 2019, Ella Lung was admitted to hospital after a fall at home. Richard had called an ambulance.

At the hospital where she was treated, safeguarding concerns were raised on the grounds she appeared unkempt and dehydrated on arrival. Richard describes this as “a suspicion of mother abuse, as baseless as it was base, and without exoneration or apology, against an old man, they knew nothing of, who had no history or record of any offenses”.

Ella remained in hospital until November 2019, when a ‘best interests’ decision was made to discharge her – but not back home with a live-in carer, as Richard wanted. Instead, with what the local authority later called Richard’s “agreement”, Ella moved into a care home. This is how Richard describes what happened. (The extracts come from his published journals.)

Dilatory and doubting social services pressured me into giving in to put Mum in a care home. She languished over one hundred days in hospitals. I had to commute by train to see her. The social worker said she was looking for a “placement,” doubting my ability to cope at home, and not pursuing the live-in carer option, even when she answered her questions. Then saying she would have to look for care homes further afield. That is to say out of my reach, against which I protested. So, I found a care home on the outskirts of town, for which “understanding” the social worker thanked me. But it was another hospital environment, leaving Ella stuck in a chair from morning till night. Social services again blocked my mother from coming home with another live-in care agency […] I was manipulated. But when manipulation failed before the reality of Mum’s misery, compulsion followed, with misrepresentation and manipulation of the reality of Mum’s wishes. I am not criticising the undoubted inadequacies of care homes but the determination of social services to prevent my mother having live-in care, instead. Economics reduces care homes to patient parking zones. […] . I thought, in the old way, that people could check themselves out of hospital. Not so. With the care home, Ella was locked-in, like a safe deposit. It appears to be underpinned by a sinister-sounding legality called “deprivation of liberties”, just another brick in the wall of the New Feudalism. A live-in care agency says that 97% of people would prefer to stay at home, when needing care. A fact towards which social services have been strangely obtuse in pursuing “best interests”. This is not a reason, it is just social services asserting its dictatorship, thanks to politicians’ passion for autocratic administrative law. While keeping a smile, Ella asked eloquently, amongst other things, why was she not allowed to go home? She was not a criminal. She hadn’t done anything wrong. […] The social services sinecure was depriving her of all faith, hope and care. (from Home Free)

By the end of 2019, Ella had already been reduced to the depths of sobbing misery, at her incarceration. Social services’ so-called minutes of her “best interest” meeting dismissed her protests as nothing but “occasional distress”. (Distress usually is occasional. That does not excuse the breach of her human rights.) Ella was not even allowed to attend, to put in a single word, of her own, about her own best interests. Whereas, the “professionals” were, as “The Chair” called them, all agreed (in group-think lock-step) to take away her freedom to go to her home, she worked so hard for, to be with the son, who lived with her, for seventy years. (from Ella sobs her heart out)

By early February 2020, following a Care Review, there was another ‘best interests’ decision to keep Ella in the care home where her mobility and nutrition were said to have improved, Richard did not agree that remaining there was in his mother’s best interests, and he reported (though it was disputed by the professionals) that Ella was unhappy there and wanted to return home.

And then came COVID-19 – with visiting restrictions, routine testing, temperature checks, and PPE.

On 30 June 2020, according to a funeral director, every single care home in town had the covid. Social services twice stopped me from bringing Mum home with a live-in carer (as told in the second book in this series). They put her life in mortal danger, as a result. Yet, their Deprivation of Liberties renewal, which they have the gall to say is for her “safeguard,” is just a rubber stamping of her imprisonment. Ella is old and frail, and we dearly want to be back together at home, as we have been, all my life. Her love will be in my heart, till I die. Social services relentlessly obstructed my mother returning home. Afterwards, I found that the abduction of the helpless young and helpless old alike, children and the elderly, from their families, amounted to a national scandal. (from Short-wave memory Mum)

Ella went on to experience various health problems, including COVID and a skin problem originally thought to be shingles.

She was reported with COVID-19 on 13 December 2020 which is a year after the social worker detained her in the care home. Ella caught a water infection in the care home and was on antibiotics for 5 days which had to be repeated resulting in terrifying and exhausting hallucinations. Also, after being taken off a pureed diet, Ella suffered a prolapse, with much loss of blood, and was rushed to hospital for emergency surgery. […] On 19 May 2021, I learned from senior staff she has the shingles, associated with age, weak immune system (vulnerable to infections), physical and emotional upset. Ella’s distress was unbearable; I was on the phone to her for nearly 2 hours.

Fearing for his own health (at over 70), as well as Ella’s, Richard restricted his visits to the care home (which also required the use of public transport). He and Ella were largely limited to near-daily telephone conversations, which Richard documented in his journals. Here are some extracts:

(I phoned Ella, in the care home, every evening — mostly getting thru — for over a year. Besides anything else, her chronic captivity was a torment to her.)

Ella: I worked hard, all my life, I only helped other people. I have no record. How did I end up in a place like this! It’s not what I saved for.

Son: I’m trying to get you out, but I have no power to do so.

Ella (with mother love, worried): Don’t work too hard at it. I don’t want you to hurt yourself. Then I won’t have you to look after me. It won’t make any difference. If they can’t be kind, there’s no help for it.

Son: I have to try (to get you home free.

Ella : I’m not stopping you from trying, but don’t over-do it. It’s no help to me, if you make yourself poorly over it…

Son: I would make it better, if I could, but I can’t. I would bring you back home.

Ella: Yes, I should be living in it, now. ‘Cos I own it. Why am I not there?

Son: The state is given too much power over family life. They’re making the excuse you’ve lost your memory…

Ella: I’ve got a good memory, for my age. Everybody has a memory lapse, and they can’t lock ‘em up, because they can’t hear [or remember things].

Son: I sympathise.

Ella: Never mind, sympathise: it’s a crime, in my opinion. Down to brass tacks: it’s wrong. I wish I was at home. I never go there.

Son: It’s social services, they won’t let you go there.

Ella: Oh dear, isn’t it terrible? You can’t go to your own home, you’ve worked all your life to get. I do miss you, and when I ring up, I get heart-ache.… It’s very cold in this attic spot…

Son: Yes, Mum.

Ella: Ridiculous, isn’t it? I don’t know what to do with myself. I just sit here, on a side seat. And I don’t know nobody personally. I want to sit near you. I don’t know why we had to be like this. I haven’t done anything wrong. You’d think they’d want (family to be together. They would be with their loved ones, I’ll bet. Why can’t I? I haven’t done anything wrong. Maybe I shouldn’t be alive.

Son: Mum, I love you with all my heart.

Ella: I know you love me, but I can’t do any good. I can’t see you; I can’t do anything. I’m so upset about that, because I should be with my loved people.

Son: The thing I feel like doing is bursting into tears.

Ella: I’m the same, and I don’t want two of us. We’ll keep our heads. I love you. I wish I was sitting with you, to talk to you (from Nobody Knows)

I’m sat in this empty bloody room. I’ve nobody to talk to. I might as well be dead, without this. How can I live without a friend or relative? Where are you? In me bed-room. I mean, can’t you come? My health is deteriorating [– tragically true — ] and I’m unhappy. […] And I’m going to die; I know I am. What else can I do? Horrible bed and walls in this horrible place. It’s not me, it’s the council. It’s no good, day after day, night after night; it’s a nightmare. Every day, without any friends, any relatives, nothing. I’m fed up with it. I’m thinking can’t you get me out of here? I can’t do that; it’s against the law. [What Ella called a wicked law: deprivation of liberties.] It’s a free country, isn’t it? Not any more. No help, nothing. It just goes on and on and on. And I die, in between. What have I done? – Nothing. Just helped people, all my life. Never had anything special for myself. Once you’re tied-up, nobody can help you. And I’m stuck in this bedroom, and I’ve no hope. […] I worked best I could. I looked after me family. What the hell is wrong with this world? – I’m not even going to talk about it. You can’t change the local law; never mind. What’s wrong with this bloody world? [I have tried to get you home.] I know you have. But it doesn’t work. You’re too good for any of ‘em. You have to do things different.… Long lonely nights; nothing to look forward to. (from Mother and Son)

Ella suffers emotionally from separation from the son she loves, in the house, she earned. She suffers mentally from a punishing imprisonment she does not deserve. And she suffers physically as a pneumonia-history patient, acutely sensitive to the cold, that a normal care home does not suit. She is 95, set to die there, because social services only obstruct.

I apologise for my imperfections of journal presentation. However, they give my aged, impaired mother, Ella the right to speak, that social services Best Interest meetings denied her. In these journals, she claims her right to love and liberty, which has been denied her.

As John Milton said, hundreds of years ago, a nation that no longer values liberty to speak the truth, becomes a sixth-rate nation. (Since 1989, Britain has had secret courts of family law, and of protection, for the young and old, respectively. Disclosers of their proceedings are thrown in jail.)

I have tried to catch the nature of Mum’s loss of a sense of time and place, in order to better understand it. I have treated her dream-like versions of reality, as her impaired mind’s functional attempts to hold her memories together, as best she can, and preserve her identity as an individual and my beloved mother.

Social services detained my mother from coming back to her house, from a care home. It’s a long story … . Ella, an impaired 95-year-old lost her memory. A treasure trove of memory is still there, but she cannot reliably access it. Having lived with my mother for seventy years, I am the one person she wants to be with. Ella still has her intelligence.

It’s as if a computer processor was still functional but is thrown on the scrap heap, for want of a memory deficiency, that could be relieved by an external memory drive. My life-long companionship puts me in a unique position to fill in Mum’s memory blanks, to the great improvement of her quality of life. Social services have obstructed that alleviation of Ella’s condition. And caused her untold distress – untold, that is, till I brought out this journal series on Family-splitting. (from So, you’ve got a prisoner mother)

Court of Protection proceedings were issued in March 2021 under Section 21A of the Mental Capacity Act 2005 and the case made its slow way through the Court of Protection, with capacity reports, witness evidence about Ella’s wishes and feelings, assessments relating to care and support needs, lists of alternative care options and balance sheets for best interests decision-making, and – towards the end – a transition plan about how Ella would be conveyed home. There were to be initial short visits home for lunch (which Richard considered just “cruel”) followed by a “trial” of living at home, with reviews at three monthly intervals.

It all proceeded slowly – as these cases usually do, but no doubt exacerbated by the pressures of the pandemic. For Richard this was all “bureaucracy” – an unconscionable delay for a beloved mother in her late nineties. Time was not on her side.

And Ella’s “shingles” was causing concern.

A visit on 8th September

Visiting nurse: Ella’s “shingles” have not improved with antibiotics. And we’ve tried two types of cream. They are maybe worse. I suggest she sees a specialist dermatologist.

Son: I agree. [That’s how they eventually found out that Ella had an aggressive skin cancer.] Also, if it’s not impertinent, I suggest, because shingles is worse with physical and emotional stress on the immune system, Ella would be better off at home.

Ella broke in: Yes, I don’t know what I’m doing here, being kept here, like I was a criminal. I want to be home to my family.

Son to nurse: I wrote a long letter, on 10 August 2020, to our GP. I was answered, by the clinic, on 10 September 2020, that: “We would be happy to give an assessment of Mrs Lung, when she comes home from the care home”.

Ella: I don’t know what I’m doing here. It’s like being a prisoner. Why can’t I go home to my family?… I’m sorry, I bet you don’t like having to keep coming to this blooming hole to see me.

Son: No, I don’t like it, but it’s worth it, to see you.

At the end of September 2021, Richard was informed that Ella been diagnosed with an aggressive cancer. He put in an urgent request for her to return home for palliative care. Ella and Richard spent 20 days at home together before Ella died.

As I read what Richard has written, and compare it with my own experience of observing more than 550 Court of Protection hearings since 2020, I recognise this family’s story in so many others. As far as I know, everyone acted in accordance with the law, and for Ella’s “best interests” and I can imagine the “mountains of official verbiage” (Richard’s words) that this case generated by way of evidence and assessment and balancing of pros and cons. I doubt anyone did anything contrary to the law, or to the guidance issued by their professional bodies – and yet the emotional devastation caused is undeniable. I have seen it many times before when people who love each other are kept apart, when strong relationships are severed. Physical safety can come at a high emotional cost.

Richard’s own distress and anger is palpable. Here’s what he’s written about the Mental Capacity Act:

The Mental Capacity Act was explicitly designed to liberate the vulnerable. But officials triumphantly claim it is in their “best interests” to be put away (profitably enslaved to their “care”). The “best interests” excuse is a latter-day “divine right” of state, which has inherited the divine right of kings.

Criminal suspects are protected by criminal law, that due process, to ensure the truth is known, by all, beyond reasonable doubt.

Ordinary civilians are exposed to the chances of civil law. Instead of objective proof of the truth, subjective assessments of a balance of probabilities, as to the truth, is ordained. This, in practise, means that the state version of events, given by professionals (those proud to make money out of a broken system) is taken as a matter of course. The government is supposed to be supporting independence, at home, for the elderly. But such cases, as have escaped to public attention, show that “a wicked law” (so-called by one of its victims, my mother, Mrs Ella Lung) of deprivation of liberties, is bitterly contested.

Family is a life-time of caring relationships, that makes for the affection, no institution can give. The state should be promoting the former, not the latter. Family love, not state power, is the foundation of society.

Mother was subjected to a Deprivation of Liberties, that deprived her of her love of freedom and her love of family, in short, her love of life. State supervision left her with an undiagnosed cancer that killed her. She might have had a few more years to enjoy her life, and be enjoyed by the company of her son. We only had each other.

My heart yearns for my mother, she was so kind, even while she wanted, so much, for so long, to be free. A country woman of the great out-doors “locked in a box,” as she said, by the state. God help her; officialdom wouldn’t.

Attempts by the local authority to prevent Richard from speaking out about this experience – citing the Transparency Order – added insult to injury. It is hugely important that families can tell their stories, because we can all learn from them. I am grateful to Richard for his reporting.

This body of words is all the body Ella has left, on this earth, this life. It isn’t much, but it is something that needed to be done, to honour her memory, and her suffering. I hope that knowledge of Ella’s state-induced misfortunes might save other helpless folk from captivity in institutions. These publications cannot now give Mother any worldly help, but they remain a witness, for the sake of other unfortunates.

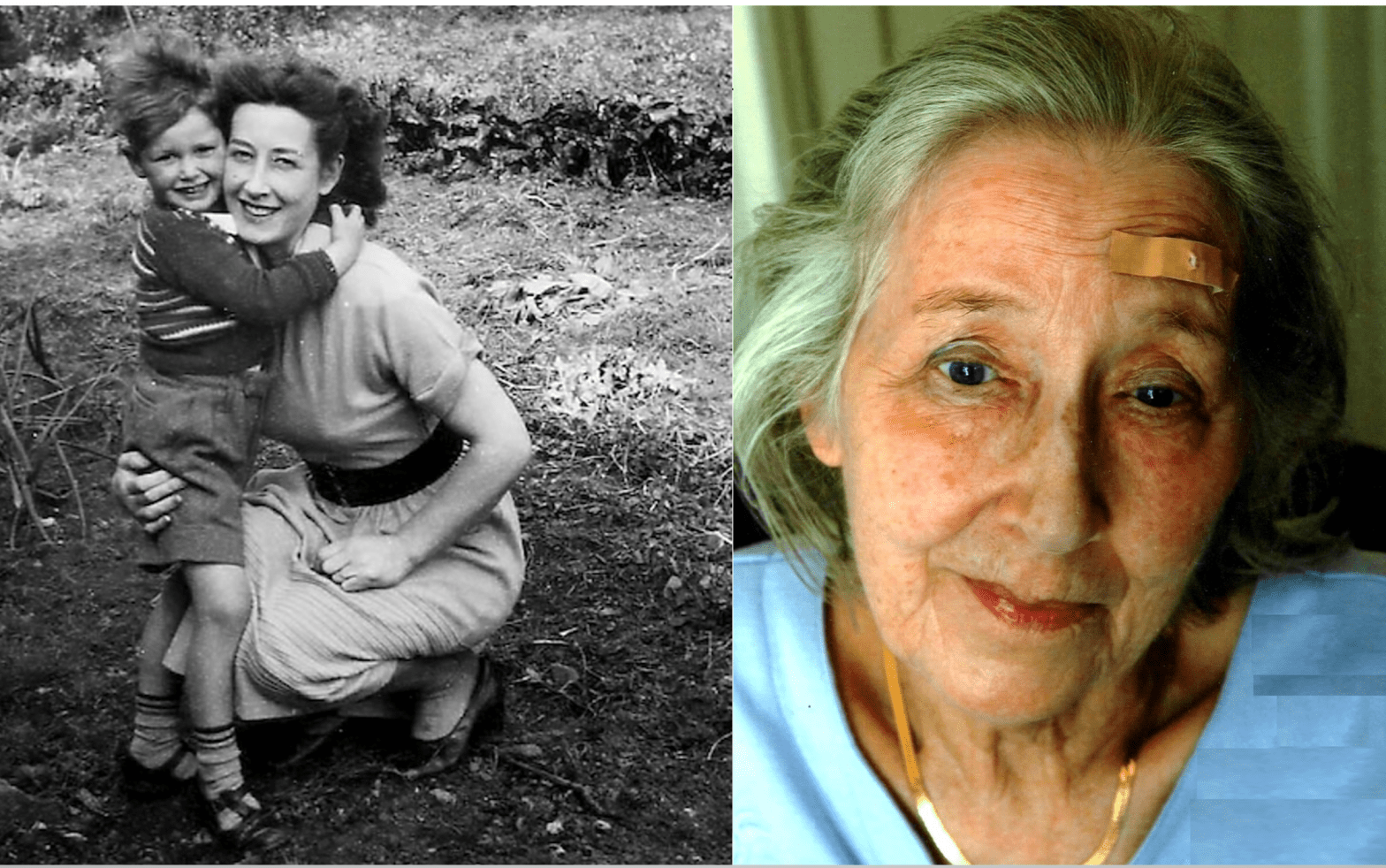

Richard Lung is the son of Ella Lung and author of many books which you can see here https://www.amazon.co.uk/stores/author/B00MFYBCWE/allbooks. Thank you to Richard for sharing the photographs of his mother (and himself as a child) which illustrate this blog post. Richard says of the photo on the left that it was taken by his Dad and “could not have been when I was more than 5 years old. That makes it 1954 or slightly earlier – so my mother would be 29 or slightly younger“. The photo on the right “was taken by Dad’s nephew shortly before Dad died, perhaps no sooner than 2011 or 2012. Mum would be 86 or 87“.

Celia Kitzinger is the co-director of the Open Justice Court of Protection Project and the Project’s blog editor. Both Richard and Celia can be contacted via the Project’s email address openjustice@yahoo.com

Appendix: Richard Lung’s journals

1. Nutcracker (social services family-splitting) June 2020

2. Home Free (How the misery makers of social services twice obstructed Mums home-coming with a live-in carer) December 2019

3. Talking To A Cat In The Moonlight (Poorly mind lovely mother) June 2020

4. Short-wave memory Mum (life-imprisoned on her life savings) July 2020

5. Impaired imprisoned innocent (speak thy grief) – summary of previous 3 titles

6. Power mannequins August 2020

7. So, you’ve got a prisoner mother September 2020

8. Ella sobs her heart out (October-December 2020)

9. Another man’s master (January 2021)

10. Nobody knows (April 2021)

11. Mother and son (April 2022)

12. A nation neglectful of the elderly (May 2022)

13. They’ve taken my life (July 2022)

14. And him me’be (May 2023)

The MCA DoLs empowers the LA, care homes and professionals to imprison P. Our daughter has a ABI and is unable to go out because it is deemed that she lacks capacity. Heartbreaking for her she has lost her life because she has suffered a brain injury. She cries and is humiliated without her autonomy every day. A modern day state asylum system for those who are disabled. It is barbaric and legal.

LikeLike

I am so sorry for you and your daughter the state is cruel to families they happy to use us for free to provide care when it suits them

LikeLike

it’s right what he says. Different circumstances, but the professionals who are supposed to protect people tear families apart. Ripping the very soul out of your daily life. Why are they allowed to make unbased accusations with no evidence and present it as if it’s fact. As a mother myself and a daughter, my mam passed in 2021. But I look after a disabled son and I fear for his future. There are fantastic care homes and carers out there but they very far and few. It’s cheaper to put people in care homes

LikeLike

Thank you so much for such a moving blog Richard – I am so pleased you got the TO changed so you could officially tell everyone your story. It is so SO important that professionals hear the voices of families like you in this way. On behalf of other families who cannot speak out – thank you.

LikeLike

Thank you for this very moving blog Richard. I’m so glad that the Transparency Order was varied so that you can speak about this experience openly.

I’m a PhD student, in the field of political theory, writing about oppression in the lives of older people. My final chapter makes the case that DoLS are oppressive (even when they’re put in place with the best of intentions). After reading this blog, and starting to read some of your journals, I’m planning to include yours and your mum’s story in that chapter.

Thank you again for sharing this, and I’m so sorry that it was so awful.

LikeLike

This was a co-operation between myself and Celia Kitzinger. Her authority has made this possible but I want to send out thanks to everyone who has or will appreciate Ella’s story. There is so much distress from split families. And Deprivation of Liberties is keeping the old asylum system going against the modern Mental Capacity Act, 2005, and sentiments like those of Lady Hale, that the mentally impaired should have equal rights, as indeed should the physically handicapped.

LikeLike

Celia Kitzinger very kindly publicised my series of 14 e-pub journals on Family-splitting. She probably should be easing off from her heavy work-load of good causes, and I don’t like to bother her.

I was published for 11 years by Smashwords. Then they merged with Draft2digital, requiring a tax exemption notification. (UK and US tax alike have provided non-functioning forms with the same result of financial disadvantage.) Notification, I gave, but the electronic form would not confirm.

Hence, d2d deleted my lifes work without compunction. That showed it was of no value to them. (Work I had done for its own sake, without pay.) Trustpilot includes one-star reviews by many deleted authors infuriated with d2d. I was particularly unfortunate to be a close-of-life author, deprived of seeing in public every book he wrote.

I don’t know if or when I can republish my books. I may be able, meanwhile, to supply any requested copy, personally.

LikeLike